International Comparisons of Unemployment Indicators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Groningen Accounting and Business Economics Traditions

University of Groningen Accounting and business economics traditions in the Netherlands Bouma, J.L.; Feenstra, D.W.; Huijgen, C.A. IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 1999 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Bouma, J. L., Feenstra, D. W., & Huijgen, C. A. (1999). Accounting and business economics traditions in the Netherlands. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 $FFRXQWLQJDQG%XVLQHVV(FRQRPLFV7UDGLWLRQVLQWKH 1HWKHUODQGV -/%RXPD':)HHQVWUD&$+XLMJHQ 8QLYHUVLW\RI*URQLQJHQ)DFXOW\RI(FRQRPLFVWKH1HWKHUODQGV Som-theme E Financial markets and institutions (Financiële markten en instellingen) $EVWUDFW Until the 1970’s Dutch accounting theorists generally showed a strong inclination towards the formulation of deductive theories. A set of different disciplines, all related to the problems of the business firm, made up a whole called “bedrijfseconomie” (business economics). -

Closer Ties: the Dutch Caribbean and the Aftermath of Empire, 1942-2012

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Closer Ties: The Dutch Caribbean and the Aftermath of Empire, 1942-2012 Chelsea Schields The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1993 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] CLOSER TIES: THE DUTCH CARIBBEAN AND THE AFTERMATH OF EMPIRE, 1942-2012 by CHELSEA SCHIELDS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 CHELSEA SCHIELDS All Rights Reserved ii Closer Ties: The Dutch Caribbean and the Aftermath of Empire, 1942-2012 by Chelsea Schields This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Professor Dagmar Herzog ______________________ _________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor Helena Rosenblatt ______________________ _________________________________________ Date Executive Officer Professor Mary Roldán Professor Joan Scott Professor Todd Shepard Professor Gary Wilder Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract Closer Ties: The Dutch Caribbean and the Aftermath of Empire, 1942-2012 by Chelsea Schields Advisor: Professor Dagmar Herzog This dissertation examines the unique trajectory of decolonization in the Netherlands and its former Caribbean colonies and argues that sexual and reproductive politics have played a pivotal role in forging a postcolonial commonwealth state. -

Global Warming and Mycoflora in the Baltic Region

ACTA MYCOLOGICA Dedicated to Vol. 41 (1): 79-94 Prof Dr. ALINA SKIRGIEŁŁO, 2006 Warszawa, with motivation of her 95th birthday Global warming and mycoflora in the Baltic Region HANNS KREISEL Zur Schwedenschanze 4, D 17498 Potthagen, [email protected] Kreisel H.: Global warming and mycoflora in the Baltic Region. Acta Mycol. 41 (1): 79 94, 2006. The author discusses possible effects of global warming on distribution and ecology of larger fungi, and presents examples of suggested indicator species which apparently are spreading from south to north. Only Basidiomycetes are corncerned, while actually no case of non lichenized Ascomycetes is known. A continued monitoring of the mentioned species is recommended. Key words: mycoflora, Basidiomycetes, global warming, Baltic Region INTRODUCTION Global warming (climatic change) with its consequences for weather and local climate, rising sea level, retreat of glaciers and of polar ice calottes, and subsequent nature catastrophes, actually is much disputed in newspapers, journals, and book publications. Highly reputed specialists of climatology, oceanography, or physics, have investigated the phenomena (e. g. Rahmstorf, Schellnhuber 2006). Since the end of last Ice Age, some 15 000 years ago, climate in central and northern Europe is warming, and enormous ice calottes have retired from this re- gion, making possible a re-settelement of large areas by vegetation and fauna. This process was not continuous, but interrupted by phases of standstill alternating with phases of further warming. Nevertheless, the actual phase of relatively fast warming is regarded as man-made to a large extent, and therefore requires special attention by scientists. Also in mycology, we are contemporary witnesses of changes in distribution and ecology of fungi, and we should use the chance to observe and describe the corre- sponding evolutions. -

RIVM Rapport 270051011 Dare to Compare! Benchmarking Dutch Health with the European Community Health Indicators (ECHI)

Dare to Compare! Benchmarking Dutch health with the European Community Health Indicators (ECHI) How does public health in the Netherlands compare to public health in other European Union (EU) countries? Are we among the top five or lagging behind? Does the picture change when focusing on specific subjects? This report compares the Netherlands to EU countries along a set of more than eighty European health indicators on, for example, disease, lifestyle and prevention. This is the first time that the indicators that make up the so-called ECHI (European Community Health Indicator) shortlist are used for benchmarking Dutch public health. This shortlist has been adopted by the EU to assist health policy makers in identifying common challenges, priorities and opportunities, and to learn from other countries’ experiences. The systematic benchmark approach also provides a detailed view on the actual availability, comparability and quality of data sets, both within the Netherlands and throughout the EU. It becomes apparent that EU-funded projects and Eurostat activities increasingly contribute to better data quality and more valid comparisons, but much work is still to be done. Dare to Compare! Given the ambition of the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport to get the Netherlands back into the top five of the healthiest European countries, a benchmark is a good exercise to identify possibilities for improvement and issues that require policy attention. This report was commissioned by the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Harbers MM | Van der Wilk EA | Kramers PGN | Kuunders MMAP | Verschuuren M | Eliyahu H | Achterberg PW Dare to Compare! RIVM Benchmarking Dutch health with the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment European Community Health Indicators (ECHI) Centre for Public Health Forecasting PO Box 1 3720 BA Bilthoven The Netherlands www.rivm.nl/ With respect to the front cover: In English the idiom ‘comparing apples and oranges’ is commonly used to indicate that some items have not been validly compared. -

Catering and Dividend Policy: Evidence from the Netherlands Over the Twentieth Century De Jong, A., Fliers, P

Catering and dividend policy: evidence from the Netherlands over the twentieth century de Jong, A., Fliers, P. T., & van Beusichem, H. C. (2019). Catering and dividend policy: evidence from the Netherlands over the twentieth century. Financial History Review, 26(3), 321-358. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0968565019000209 Published in: Financial History Review Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2019 Cambridge University Press. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:24. Sep. 2021 Catering and Dividend Policy: Evidence from the Netherlands over the Twentieth Century ABE DE JONG*, PHILIP FLIERS# AND HENRY VAN BEUSICHEM† August 2019 Forthcoming in Financial History Review * Corresponding author. Monash University, Australia and Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, The Netherlands, email: [email protected]. -

Trends in Absolute Income Mobility in North America and Europe

Trends in Absolute Income Mobility in North America and Europe dynamicsofinequality.org DIAL Working Paper Series 04/2021 Robert Manduca, Maximilian Hell, Adrian Adermon, Jo Blanden, Espen Bratberg, Anne C. Gielen, Hans van Kippersluis, Keun Bok Lee, Stephen Machin, Martin D. Munk, Martin Nybom, Yuri Ostrovsky, Sumaiya Rahman, Outi Sirniö This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 0 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 724363 Trends in Absolute Income Mobility in North America and Europe Robert Manduca1, Maximilian Hell2, Adrian Adermon3, Jo Blanden4, Espen Bratberg5, Anne C. Gielen6, Hans van Kippersluis7, Keun Bok Lee8, Stephen Machin9, Martin D. Munk10, Martin Nybom11, Yuri Ostrovsky12, Sumaiya Rahman13, & Outi Sirniö14 Abstract We compute rates of absolute upward income mobility for the 1960-1987 birth cohorts in eight countries in North America and Europe. Rates and trends in absolute mobility varied dramatically across countries during this period: the US and Canada saw upward mobility rates near 50% for recent cohorts, while countries like Norway and Finland saw sustained rates above 70%. Decomposition analysis suggests that differences in the marginal income distributions, especially the amount of cross-cohort income inequality, were the primary driver of differing mobility rates across countries. We also demonstrate that absolute mobility rates can be accurately estimated without linked parent-child data. 1 Assistant Professor Robert Manduca, Department of Sociology, University of Michigan, [email protected] 2 Dr. Maximilian Hell, Department of Sociology, Stanford University, [email protected] 3 Dr. Adrian Adermon, Institute for Evaluation of Labor Market and Education Policy, [email protected] 4 Dr. -

04.06.2016 Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, School of Theology

ARISTOTLE UNIVERSITY OF THESSALONIKI SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY SUMMER SCHOOL ON HUMAN RIGHTS “STAND UP FOR WOMEN’S AND CHILDREN’S RIGHTS” 31.05 – 04.06.2016 Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, School of Theology Brief biographies of speakers/moderators SVANHVIT ADALSTEINSDOTTIR is an adviser with the Office of the Special representative of Women peace and security at NATO. She is an Icelandic national and has been with the Ministry for Foreign Affairs in Iceland since 1998, most recently at the Directorate for Development and the Iceland Crisis Response Unit. She was active in the last update of the Icelandic National Action Plan for implementations of UNCR 1325 and has recently been involved with updating the 1325 NATO/EAPC Action Plan on Women Peace and Security. THE VENERABLE CHRISTINE ALLSOPP Christine was one of the first women to be ordained a priest in the Church of England in 1994. In 2005 she was the sixth woman to be appointed to the senior role of Archdeacon. She served on the Church of England’s General Synod, campaigning for legislation to allow women to be bishops. She is currently a member of the executive committee of the Anglican- Lutheran Society. Page 1 of 10 ARISTOTLE UNIVERSITY OF THESSALONIKI SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY LUCA BARATTO, is a Waldensian pastor. He works for the Communication service of the Federation of Protestant Churches in Italy (FCEI). He is also responsible for the Radio programme “Culto evangelico” broadcasted by RadiounoRAI (www.cultoevangelico.rai.it). REV BILL CAVE is a Church of England Prison Chaplain, with 20 years’ experience of different prison regimes and situations. -

Special Issue

TABLE OF CONTENTS Special Issue: 1. Sheila Dauer………………………………………………………… 1 INTRODUCTION: ANTHROPOLOGICAL APPROACHES TO GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE Anthropological Approaches to 2. Melissa A. Beske……………………………………………………. 16 Gender-based AN ANALYSIS OF THE COLLABORATIVE ENDEAVORS TO LESSEN Violence and GENDER-BASED INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE IN CAYO, BELIZE, AND A CASE FOR ANTHROPOLOGICAL ENGAGEMENT Human Rights 3. Janet Chernela ……………………………….……………………. 34 PARTICULARIZING UNIVERSALS/UNIVERSALIZING PARTICULARS: A COMPREHENSIVE APPROACH TO TRAFFICKING IN INDIGENOUS WOMEN AND GIRLS IN THE NORTHWEST AMAZON OF BRAZIL 4. Rebecka Lundgren and Melissa K. Adams……………….……… 53 SAFE PASSAGES: BUILDING ON CULTURAL TRADITIONS TO PREVENT GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE THROUGHOUT THE LIFE COURSE 5. Shannon Speed …………………………………………………….. 78 A DREADFUL MOSAIC: RETHINKING GENDER VIOLENCE THROUGH THE LIVES OF INDIGENOUS WOMEN MIGRANTS Working Paper #304 June 2014 Gender, Development, and Globalization Program Center for Gender in Global Context Michigan State University 206 International Center 427 N Shaw Ln, East Lansing, MI 48824-1035 Ph: 517/353-5040 • Fx: 517/432-4845 Email: [email protected] • Web: http://www.gencen.msu.edu See back page for ordering information and call for papers Copyright © 2014 MSU Board of Trustees Introduction: Anthropological Approaches to Gender-based Violence Sheila Dauer Graduate Program in International Affairs New School for Public Engagement Biography Sheila Dauer is the former Director of Amnesty International USA (AIUSA)’s Women’s Human Rights Program during the program’s existence from October 1997 to December 2008. She was on the staff of AIUSA from 1979 to 2008. As a charter member of an AIUSA Taskforce on Women’s Human Rights since 1988, she worked with both AI’s international research office and other national sections to develop AI’s policy, action, and publications on women’s human rights. -

Catering and Dividend Policy: Evidence from the Netherlands Over the Twentieth Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen's University Research Portal Catering and Dividend Policy: Evidence from the Netherlands over the Twentieth Century de Jong, A., Fliers, P. T., & van Beusichem, H. C. (Accepted/In press). Catering and Dividend Policy: Evidence from the Netherlands over the Twentieth Century. Financial History Review. Published in: Financial History Review Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2019 Cambridge University Press. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:10. Sep. 2019 Catering and Dividend Policy: Evidence from the Netherlands over the Twentieth Century ABE DE JONG*, PHILIP FLIERS# AND HENRY VAN BEUSICHEM† August 2019 Forthcoming in Financial History Review * Corresponding author. -

Online Appendix 1 Analytical Results for the Representative-Agent Model 2 Micro-Data on the Cross-Sectional Distribution

Online Appendix 1 Analytical results for the representative-agent model The steady-state equilibrium is characterized by the following equations. 1 = [1 + r(1 k)] (1) (1 l)w = (2) C K w = (1 ) (3) E 1 K r + = (4) E C = (1 l)wE + r(1 k)K + T (5) G + T = lwE + krK. (6) Proof of Lemma 1 Rearranging (1) gives 1 1 r = 1 . 1 k This can be combined with (4) to yield 1 1 K = E 0 1 1 1 + 1 1 k @ A which shows that K/E does not depend on l. K Proof of Proposition 2 Since H does not depend on l, (3) and (4) imply that w and r do not change with respect to changes in l across steady states. 2 Micro-data on the cross-sectional distribution Calibration uses statistics based on samples from the 2005 Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) along with the Supplemental Wealth File. The original 2005 wave of the PSID covers about 8,000 1 representative U.S. households. I use both the PSID core families and the immigrant sample families that were added in 1997 and 1999, and thus use the weights provided by the PSID. I consider samples whose age is between 18 and 70. I exclude those whose main job is self-employment, given that the focus of this paper is on labor supply. The size of the final samples is 6,493. A household is defined as employed if the household head’sannual hours worked is greater than 1,000 hours since this paper focuses on full-time employment. -

Author Report No Available From

e ED 241 756 CE 038 546 AUTHOR Kulich, Jindra, Comp.. TITLE Adult Education in Continental Europe: an Annotated Biblio raphy of English-language Materials 1980-1982. MoPogr phs on Comparative and Area Studies in Adult Educat !on. INSTITUTION British Columbia Univ., Vancouver. Centre for Continuing Education.; International Council for Adult Education, Toronto (Ontario)., REPORT NO ISBN-0-88843-131-7 PUB DATE 84, NOTE 182p.; For a related doCument, see ED 221 744. AVAILABLE FROMCentre for Continuing Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 2A4 0 ($15.00). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) . EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO8 Plus Postage. .. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Adult Education; Adult Educators; *Adult Learning; Adult Literacy; Agricultural Education; Apprenticeships; Community Development; *Comparative Education; Consumer Education; Continuing Education; Correspondence Study; Educational Finance; Educational History; Educational Research; Educational Television; *English Curriculum; Extension Education; Library Extension; Lifelong Learning; Military Training; Museums; Physical Education; Postsecondary Education; Religious Education; Retirement; Retraining; Secondary Education; State Programs; Trade and Industrial Education; Vocational Education; Womens Education IDENTIFIERS *Europe; *Scandinavia ABSTRACT .This bibliography contains 682 listings covering English language materials on adult education in Europe published during 1980-82. Materials were chosen in accord with a broad definition of adult education that includes vocational education for adults; training in business and industry; adult secondary and postsecondary study; activities of museums, art galleries, and libraries; along with liberal adult education through university extension and evening classes or through voluntary associations. Materials selected are readily accessible. ThZ bibliography is organized by country, with a section on Europe and a section on Scandinavia. -

Currant Varieties (PDF)

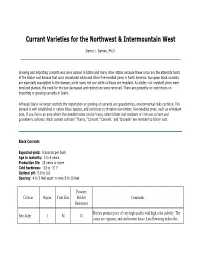

Currant Varieties for the Northwest & Intermountain West Danny L. Barney, Ph.D. Growing and importing currants was once banned in Idaho and many other states because these crops are the alternate hosts of the blister rust disease that once devastated white and other five-needled pines in North America. European black currants are especially susceptible to the disease, while many red and white cultivars are resistant. As blister rust resistant pines were bred and planted, the need for the ban decreased and restrictions were removed. There are presently no restrictions on importing or growing currants in Idaho. Although Idaho no longer restricts the importation or growing of currants and gooseberries, environmental risks continue. The disease is well established in native Ribes species, and continues to threaten non-timber, five-needled pines, such as whitebark pine. If you live in an area where five-needled pines can be found, select blister rust resistant or immune currant and gooseberry cultivars. Black currant cultivars 'Titania,' 'Consort,' 'Coronet,' and 'Crusader' are resistant to blister rust. Black Currants Expected yield: 5 pounds per bush Age to maturity: 3 to 4 years Productive life: 15 years or more Cold hardiness: -20 to -31 F Optimal pH: 5.8 to 6.8 Spacing: 4 to 5 feet apart in rows 8 to 10 feet Powdery Cultivar Ripens Fruit Size Mildew Comments Resistance Berries produce juice of very high quality with high color stability. The Ben Alder 1 M G canes are vigorous, and can become dense. Late flowering makes this cultivar somewhat resistant to spring frosts. High yielding under ideal conditions, but low yields and marked susceptibility to white pine blister rust have been reported from the northeastern United States.