Augusta Fells Savage 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornell Alumni News

Cornell Alumni News Volume 46, Number 22 May I 5, I 944 Price 20 Cents Ezra Cornell at Age of Twenty-one (See First Page Inside) Class Reunions Will 25e Different This Year! While the War lasts, Bonded Reunions will take the place of the usual class pilgrimages to Ithaca in June. But when the War is won, all Classes will come back to register again in Barton Hall for a mammoth Victory Homecoming and to celebrate Cornell's Seventy-fifth Anniversary. Help Your Class Celebrate Its Bonded Reunion The Plan is Simple—Instead of coming to your Class Reunion in Ithaca this June, use the money your trip would cost to purchase Series F War Savings Bonds in the name of "Cornell University, A Corporation, Ithaca, N. Y." Series F Bonds of $25 denomination cost $18.50 at any bank or post office. The Bonds you send will be credited to your Class in the 1943-44 Alumni Fund, which closes June 30. They will release cash to help Cornell through the difficult war year ahead. By your participation in Bonded Reunions: America's War Effort Is Speeded Cornell's War Effort Is Aided Transportation Loads Are Eased Campus Facilities ^re Saved Your Class Fund Is Increased Cornell's War-to-peace Conversion Your Money Does Double Duty Is Assured Send your Bonded Reunion War Bonds to Cornell Alumni Fund Council, 3 East Avenue, Ithaca, N. Y. Cornell Association of Class Secretaries Please mention the CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS Volume 46, Number 22 May 15, 1944 Price, 20 Cents CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS Subscription price $4 a year. -

Hubert H. Harrison Papers, 1893-1927 MS# 1411

Hubert H. Harrison Papers, 1893-1927 MS# 1411 ©2007 Columbia University Libraries SUMMARY INFORMATION Creator Harrson, Hubert H. Title and dates Hubert H. Harrison Papers, 1893-1927 Abstract Size 23 linear ft. (19 doucument boxes; 7 record storage cartons; 1 flat box) Call number MS# 1411 Location Columbia University Butler Library, 6th Floor Rare Book and Manuscript Library 535 West 114th Street New York, NY 10027 Hubert H. Harrison Papers Languages of material English, French, Latin Biographical Note Born April 27, 1883, in Concordia, St. Croix, Danish West Indies, Hubert H. Harrison was a brilliant and influential writer, orator, educator, critic, and political activist in Harlem during the early decades of the 20th century. He played unique, signal roles, in what were the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the New Negro/Garvey movement) of his era. Labor and civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph described him as “the father of Harlem radicalism” and historian Joel A. Rogers considered him “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time” and “one of America’s greatest minds.” Following his December 17, 1927, death due to complications of an appendectomy, Harrison’s important contributions to intellectual and radical thought were much neglected. In 1900 Harrison moved to New York City where he worked low-paying jobs, attended high school, and became interested in freethought and socialism. His first of many published letters to the editor appeared in the New York Times in 1903. During his first decade in New York the autodidactic Harrison read and wrote constantly and was active in Black intellectual circles at St. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman"

Cummer Museum Presents "Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman" artandobject.com/news/cummer-museum-presents-augusta-savage-renaissance-woman Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY Augusta Savage, Portrait of a Baby, 1942. Terracotta. JACKSONVILLE, Fla. – Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman is the first exhibition to reassess Savage’s contributions to art and cultural history through the lens of the artist-activist. Organized by the Cummer Museum and featuring sculptures, paintings and works on paper, the show is on view through April 7, 2019. Savage is a native of Green Cove Springs, near Jacksonville, and became a noted Harlem Renaissance leader, educator, artist and catalyst for change in the early 20th century. The exhibition, curated by the Cummer Museum and guest curator Jeffreen M. Hayes, Ph.D., brings together works from 21 national public and private lenders, and presents Savage’s small- and medium-size sculptures in bronze and other media alongside works by artists she mentored. Many of the nearly 80 works on view are rarely seen publicly. 1/3 “While Savage’s artistic skill was widely Walter acclaimed nationally and internationally O. during her lifetime, this exhibition Evans provides a critical examination of her artistic legacy,” said Hayes. “It positions Savage as a leading figure whose far- reaching and multifaceted approach to facilitating cultural and social change is especially relevant in terms of today’s interest in activism.” A gifted sculptor, Savage (1892-1962) overcame poverty, racism and sexual discrimination to become one of the most influential American artists of the 20th century, playing a pivotal role in the development of some of this country’s most celebrated artists, including William Artis, Romare Bearden, Gwendolyn Bennett, Robert Blackburn, Gwendolyn Knight, Jacob Lawrence and Norman Lewis. -

The Studio Homes of Daniel Chester French by Karen Zukowski

SPRING 2018 Volume 25, No. 1 NEWSLETTER City/Country: The Studio Homes of Daniel Chester French by karen zukowski hat can the studios of Daniel Chester French (1850–1931) tell us about the man who built them? He is often described as a Wsturdy American country boy, practically self-taught, who, due to his innate talent and sterling character, rose to create the most heroic of America’s heroic sculptures. French sculpted the seated figure in Washington, D.C.’s Lincoln Memorial, which is, according to a recent report, the most popular statue in the United States.1 Of course, the real story is more complex, and examination of French’s studios both compli- cates and expands our understanding of him. For most of his life, French kept a studio home in New York City and another in Massachusetts. This city/country dynamic was essential to his creative process. BECOMING AN ARTIST French came of age as America recovered from the trauma of the Civil War and slowly prepared to become a world power. He was born in 1850 to an established New England family of gentleman farmers who also worked as lawyers and judges and held other leadership positions in civic life. French’s father was a lawyer who eventually became assistant secretary of the U.S. Treasury under President Grant. Dan (as his family called him) came to his profession while they were living in Concord, Massachusetts. This was the town renowned for plain living and high thinking, the home of literary giants Amos Bronson Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau at Walden Pond nearby. -

2425 Hermon Atkins Macneil, 1866

#2425 Hermon Atkins MacNeil, 1866-1947. Papers, [1896-l947J-1966. These additional papers include a letter from William Henry Fox, Secretary General of the U.S. Commission to the International Exposition of Art and History at Rome, Italy, in 1911, informing MacNeil that the King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, is interested in buying his statuette "Ai 'Primitive Chant", letters notifying MacNeil that he has been made an honorary member of the American Institute of Architects (1928) and a fellow of the AmRrican Numismatic Society (1935) and the National Sculpture Society (1946); letters of congratulation upon his marriage to Mrs. Cecelia W. Muench in 1946; an autobiographical sketch (20 pp. typescript carbon, 1943), certificates and citations from the National Academy of Design, the National Institute of Arts and letters, the Architectural League of New York, and the Disabled American Veterans of the World War, forty-eight photographs (1896+) mainly of the artist and his sculpture, newspaper clippings on his career, and miscellaneous printed items. Also, messages of condolence and formal tri butes sent to his widow (1947-1948), obituaries, and press reports (1957, 1966) concerning a memorial established for the artist. Correspondents include A. J. Barnouw, Emile Brunet, Jo Davidson, Carl Paul Jennewein, Leon Kroll, and many associates, relatives, and friends. £. 290 items. Maim! entry: Cross references to main entry: MacNeil, Hermon Atkins, 1866-1947. Barnouw, Adrian Jacob, 1877- Papers, [1896-l947J-1966. Brunet, Emile, 1899- Davidson, Jo, 1883-1951 Fox, William Henry Jennewein, Carl Paul, 1890- Kroll, Leon, 1884- Muench, Cecelia W Victor Emmanuel III, 1869-1947 See also detailed checklists on file in this folder. -

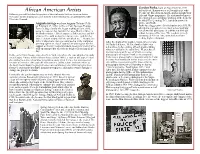

Artist Insert for Web.Indd

Gordon Parks, born on November 30, 1912 in Fort Scott, Kansas was a self-taught artist who became the fi rst African-American photographer for Following you will fi nd short biographies of three infl uential African American Artists. Life and Vogue magazines. He also pursued movie The source for this information came from the website Biography.com published by A&E directing and screenwriting, working at the helm for Television Network. the fi lms The Learning Tree, based on a novel he Augusta Savage was born Augusta Christine Fells wrote, and Shaft. on February 29, 1892, in Green Cove Springs, Florida. Parks faced aggressive discrimination as a child. He Part of a large family, she began making art as a child, attended a segregated elementary school and was using the natural clay found in her area. But her father, a not allowed to participate in activities at his high Methodist minister, didn’t approve of this activity and did school because of his race. The teachers actively whatever he could to stop her. Savage once said that her discouraged African-American students from father “almost whipped all the art out of me.” Despite her seeking higher education. father’s objections, Savage continued to make sculptures After the death of his mother, Sarah, when he was winning a prize in a local county fair which gave her the 14, Parks left home. He lived with relatives for support of the fair’s superintendent, George Graham Currie a short time before setting off on his own, taking who encouraged her to study art despite the racism of the whatever odd jobs, he could fi nd. -

12 Recent Acquisitions, April 2021 [email protected] 917-974-2420 Full Descriptions Available at Or Click on Any Image

12 Recent Acquisitions, April 2021 [email protected] 917-974-2420 full descriptions available at www.honeyandwaxbooks.com or click on any image WHIMSICAL NINETEENTH-CENTURY SEWING CARDS 1. [DESIGN]. Farbige Ausnähbilder (Colored Sewing Pictures). Germany: circa 1890. $1000. A graphically striking group of large-format nineteenth-century German sewing cards, designed as an entertainment and fine motor exercise for children. Marked with spaced dots for a needle to enter, the images include well-dressed children playing with a puppet, a ball, a parasol, and a shovel. A boy draws a caricature beneath his math problem; a girl prepares her dog for a walk; a younger child assembles all the props for a round of dress-up. There are also three separate images of children wielding pipes, one boy in a top hat actively smoking. Housed in its original color-printed envelope, this set is presumed incomplete: most images appear in one copy, two images in two copies, and one image in three. Not in OCLC. An unusual survival, cards unused and nearly fine. Group of fifteen color-printed sewing cards, measuring 8 x 6 inches. Two cards with light marginal browning. Housed in original envelope with color pictorial pastedown label. LET US NOW PRAISE FAMOUS MEN BY JAMES AGEE AND WALKER EVANS, FROM THE LIBRARY OF HUNTER S. THOMPSON 2. James Agee; Walker Evans; [Hunter S. Thompson]. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, (1960). $2500. First expanded edition, following the 1941 first edition, of a landmark work of American journalism, from the library of Hunter S. -

CREATING COMMUNITY. CINQUE GALLERY ARTISTS MAY 3 – JULY 4, 2021 1 Charles Alston

CREATING COMMUNITY. CINQUE GALLERY ARTISTS MAY 3 – JULY 4, 2021 1 Charles Alston. Emma Amos. Benny Andrews. Romare Bearden. Dawoud Bey. Camille Billops. Robert Blackburn. Betty Blayton-Taylor. Frank Bowling. Vivian Browne. Nanette Carter. Elizabeth Catlett-Mora. Edward Clark. Ernest Crichlow. Melvin Edwards. Tom Feelings. Sam Gilliam. Ray Grist. Cynthia Hawkins. Robin Holder. Bill Hutson. Mohammad Omar Khalil. Hughie Lee-Smith. Norman Lewis. Whitfield Lovell. Alvin D. Loving. Richard Mayhew. Howard McCalebb. Norma Morgan. Otto Neals. Ademola Olugebefola. Debra Priestly. Mavis Pusey. Ann Tanksley. Mildred Thompson. Charles White. Ben Wigfall. Frank Wimberley. Hale Woodruff ESSAY BY GUEST EXHIBITION CURATOR, SUSAN STEDMAN RECOLLECTION BY GUEST PROGRAMS CURATOR, NANETTE CARTER 2 CREATING COMMUNITY. CINQUE GALLERY ARTISTS CREATING COMMUNITY. CINQUE GALLERY ARTISTS Charles Alston. Emma Amos. Benny Andrews. Romare Bearden. Dawoud Bey. Camille Billops. Robert Blackburn. Betty Blayton-Taylor. Frank Bowling. Vivian Browne. Nanette Carter. Elizabeth Catlett-Mora. Edward Clark. Ernest Crichlow. Melvin Edwards. Tom Feelings. Sam Gilliam. Ray Grist. Cynthia Hawkins. Robin Holder. Bill Hutson. Mohammad Omar Khalil. Hughie Lee-Smith. Norman Lewis. Whitfield Lovell. Alvin D. Loving. Richard Mayhew. Howard McCalebb. Norma Morgan. Otto Neals. Ademola Olugebefola. Debra Priestly. Mavis Pusey. Ann Tanksley. Mildred Thompson. Charles White. Ben Wigfall. Frank Wimberley. Hale Woodruff ESSAY BY GUEST EXHIBITION CURATOR, SUSAN STEDMAN RECOLLECTION BY GUEST PROGRAMS CURATOR, NANETTE CARTER MAY 3 — JULY 4, 2021 THE PHYLLIS HARRIMAN MASON GALLERY THE ART STUDENTS LEAGUE OF NEW YORK Cinque Gallery Announcement. Artwork by Malcolm Bailey (1947—2011). Cinque Gallery Inaugural, Solo Exhibition, 1969—70. 3 CREATING COMMUNITY. CINQUE GALLERY ARTISTS A CHRONICLE IN PROGRESS Former “306” colleagues. -

Exhibition of I'roduc ['Ions By

EXHIBITION OF I'RODUC ['IONS BY NEURO ARTISTS WOMAN HOLDING A JUG James A. Porter 1'KBSKNTIiD BY TUB H ARMON FOUNDATIO N AT THE ART C E N T I: R 193 3 PEARL Sjrgent Johnson Recipient of the Roben C. Ugden Prize of fiJ0 'Ilie Picture''^^r^Ä;Ä,sÄ^^ by James .1. I ft'^'/!t All the photogtaphic Kork for this catalog ami tl„- i-\i„h ;• , , e ^mesLat^Al!en,213W:tJ^ZTZ7o^^T" Negro photographer THF HARMON FOUNDATION IN COOPERATION WITH THE NATIONAL ALLIANCE OF ART AND INDUSTRY PRES E S' T S A S' E N H I B I T I O N O F W 0 R K 1! V N F G R O AR TI S TS A T T H E A R T C E N T K R 65 RAST ?6TH STREET NEW YORK, X. Y. February 2(1 to March 4, 1933 l inclusive) Weck Days from 10 A.M. to 6 P.M. Sunday, February 26, from 1 to 6 P.M. Evenings of February 20, 2S, 27 and March 2, until ten o'clock Il A R M O X F O U N 1) AT 1 O X INCORPORATKD 140 NASSAU STREET NEW YORK, N. Y. \V. Burke Harmon, President Helen Griffiths Harmon, Vice President Samuel Medine Lindsay, Economic Advise Mary Beattie Brady, Director Evelyn S. Brown, Assistant Director PROFILE OF NEGRO GIRL Eirl: Wi'.ton Richardson Received the Hon Bernent P trina! Prize of $75. FOREWORD 'l'Ili'". 1933 exhibition of work by Negro artists spoiv -*- sored by the Harmon Foundation is the fifth held by the organization in the City of New York. -

HIST 103-001: AMERICAN PLURALISM Fall 20201

HIST 103-001: AMERICAN PLURALISM Fall 20201 Prof. Timothy J. Gilfoyle, for asynchronous (recorded) online lectures, MW, 1:30-2:20pm Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.luc.edu/history/faculty/gilfoyle.shtml he, him, his Zoom Office Hours: Monday, 9:30-12 noon & by appointment Junior Professors for synchronous (live) online Zoom discussions and section times: Nathan Ellstrand: Mon. 2:50-3:40pm (Section 121); 4:10-5pm (Section 120) Anthony Stamilio: Fri. 10:50-11:40 (Section 124); 12:10-1pm (Section 125) COURSE DESCRIPTION “Without a vivid link to the past, the present is chaos and the future unreadable.” Jason Epstein This course explores the multicultural origins and social evolution of the United States, sometimes called the “American republican experiment." The course focuses on major conflicts and themes from the pre-Columbian era to the present as they affected the pluralistic variety of ethnic, racial, religious, economic and sexual groups that ultimately produced something called "Americans." American civic culture cherishes both liberty and equality, individual freedom and social justice. These impulses, frequently in conflict with each other, pervade political, economic, and social life in the United States. This course provides an introduction to the history of these tensions as they shaped the American polity. Since much of this history remains unknown, forgotten, or shrouded in mythology, the course provides a framework to understand and critique American democracy. Many of the American revolutionaries believed the study of history was a prerequisite to citizenship, for a society or community with little knowledge of its past has little chance of comprehending its own identity. -

The Thurston Collection of Laboratory Artifacts at Cornell University

The Thurston Collection of Laboratory Artifacts at Cornell University ! Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering An ASME Heritage Collection !2 of !20 Mechanical Engineering Heritage Collection Robert H. Thurston Collection – Cornell University Early Engineering Laboratory Devices and Testing Machines The devices in this collection, used at Cornell between 1885 and 1905, exemplify Robert Henry Thurston’s vision of the central role of the engineering laboratory in training mechanical engineers. Building on his work at Stevens Institute of Technology, Thurston fully implemented his vision at Cornell’s Sibley College of Mechanical Engineering and Mechanic Arts, which under his leadership became the largest and most influential mechanical engineering program in the U.S. Thurston’s emphasis on engineering laboratories achieved national and international recognition as the key to moving engineering training from shop to university. American Society of Mechanical Engineers 2019 College of Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York Founded in 1865 Lance Collins, Ph.D., Professor and Dean Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Mark Campbell, Ph.D., Professor and Director Cover illustrations: Top: Large gear from the Thurston torsion testing machine, 1880; Middle: Thurston’s lubrication testing machine c.1873. Photos; FC Moon !3 of !20 Robert Henry Thurston Collection of 19th Century Engineering Laboratory Equipment The Thurston Collection consists of laboratory testing machines and pedagogical tools used to instruct mechanical engineering students at Cornell’s Sibley School of Mechanical Engineering during the late 19th century (see list of artifacts on p. 11). Its historical importance is due to its association with Robert H. Thurston. Thurston was the leading proponent of the engineering testing laboratory as a means of giving mechanical engineering students training that would be, simultaneously practical and scientific.