Connie Cabrera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ùرانك سùšù†Ø§Øªø±Ø§ ألبوù… قائم Ø

ÙØ ±Ø§Ù†Ùƒ سيناترا ألبوم قائم Ø© (الألبومات & الجدول الزم ني) Robin and the 7 Hoods – Original Score https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/robin-and-the-7-hoods-%E2%80%93- From The Motion Picture Musical Comedy original-score-from-the-motion-picture-musical-comedy-7352898/songs https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/songs-for-swingin%27-lovers%21- Songs for Swingin' Lovers! 1041548/songs 12 Songs of Christmas https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/12-songs-of-christmas-4548728/songs L.A. Is My Lady https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/l.a.-is-my-lady-2897354/songs I Remember Tommy https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/i-remember-tommy-2897925/songs Nice 'n' Easy https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/nice-%27n%27-easy-2897970/songs Sinatra & Company https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/sinatra-%26-company-1747713/songs https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/trilogy%3A-past-present-future- Trilogy: Past Present Future 614317/songs https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ol%27-blue-eyes-is-back- Ol' Blue Eyes Is Back 3881424/songs https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/a-swingin%27-affair%21- A Swingin' Affair! 1419881/songs The Sinatra Family Wish You a Merry https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-sinatra-family-wish-you-a-merry- Christmas christmas-2898718/songs Young at Heart https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/young-at-heart-8058542/songs Sings Days of Wine and Roses, Moon River https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/sings-days-of-wine-and-roses%2C- -

Following Hit Trail

August 4, 1962 50 Cents B1ILLE31:1A11:11111 IN/R..11910 WEEK Music -Phonograph Merchandising Radio -Tv Programming Coin Machine Operating Teen -Angle Albums MUSICBILLBOARD WEEK PAGE ONE RECORDS PAGE ONE RECORD Following Hit Trail SINGLES ALBUMS Blazed by Singles The slight pickup in LP sales which started in mid -July continued last week, sparked mainly by hit LP's with pop * NATIONAL BREAKOUTS * NATIONAL BREAKOUTS artists and a number of movie sound tracks. Though this was true in most markets there were a number of areas where LP SHE'S NOT YOU, ElvisPresley, RCA Victor MONO sales were still sluggish. Where LP business ranged from good 8041 to strong it was the fast sales pace of the hit items, especially ROSES ARE RED, Bobby Vinton, Epic LN 24020 the newer LP's, that created most of thetraffic.Hit LP's appear to be jumping to the top of charts at a much faster rate than they used to, and grabbing sales immediate?), upon STEREO release instead of after a month or two on the market. More and more the LP business, according to dealers,is following * REGIONAL BREAKOUTS No Breakouts This Week. the hit trend of the singles record market, perhaps because so These new records, not yet on BMW's Hot 100, have many of the new albums are teen -oriented. been reported getting strong sales action by dealers Meanwhile, singles business continued to flow its happy in major market(s)listedinparenthesis. way, with dealers and rackers reporting that this summer's 45 * NEW ACTION LP'S sales are the best in the last three summers. -

In This White House Guests: Ambassador Deborah Birx and Emily Procter

The West Wing Weekly 2:04: In This White House Guests: Ambassador Deborah Birx and Emily Procter [Intro music] JOSH: You’re listening to The West Wing Weekly. I’m Joshua Malina. HRISHI: And I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. Today we’re talking about season 2, episode 4. It’s called “In This White House” and we’ll be joined later on by special guest Emily Procter who makes her first appearance in The West Wing as Ainsley Hayes. JOSH: The teleplay is by Aaron Sorkin. The story by Peter Parnell and Allison Abner. This episode was directed by Ken Olin and it originally aired on October 25th, 2000. HRISHI: Here’s a synopsis from TV Guide. “The West Wing gets a right-winger as young republic lawyer Ainsley Hayes signs on as associate White House counsel. She’s offered the job at the insistence of the President after he sees her demolish Sam on a TV talk show. Meanwhile, the president of an AIDS ravaged African country visits the White House and spars with drug company executives.” JOSH: So, our discussion of this episode with Emily Procter is coming up, but first since the AIDS crisis in Africa is a central part of this episode we wanted to get some real-world context for the issue. HRISHI: I spoke to Ambassador-at-Large Deborah Birx. She was previously the director of the CDC’s division of global HIV and AIDS and now she serves as the United States Global AIDS Coordinator. DEBORAH: This is Debbie Birx, the Global AIDS Coordinator from the US Department of State. -

Rick L. Pope Phonograph Record Collection 10 Soundtrack/WB/Record

1 Rick L. Pope Phonograph Record Collection 10 soundtrack/WB/record/archives 12 Songs of Christmas, Crosby, Sinatra, Waring/ Reprise/record/archives 15 Hits of Jimmie Rodgers/Dot / record/archives 15 Hits of Pat Boone/ Dot/ record/archives 24 Karat Gold From the Sound Stage , A Double Dozen of All Time Hits from the Movies/ MGM/ record/archives 42nd Street soundtrack/ RCA/ record/archives 50 Years of Film (1923-1973)/WB/ record set (3 records and 1 book)/archives 50 Years of Music (1923-1973)/WB/ record set (3 records and 1 book)/archives 60 years of Music America Likes Best vols 1-3/RCA Victor / record set (5 pieces collectively)/archives 60 Years of Music America Likes Best Vol.3 red seal/ RCA Victor/ record/archives 1776 soundtrack / Columbia/ record/archives 2001 A Space Oddyssey sound track/ MGM/ record/archives 2001 A Space Oddyssey sound track vol. 2 / MCA/ record/archives A Bing Crosby Christmas for Today’s Army/NA/ record set (2 pieces)/archives A Bing Crosby Collection vol. 1/ Columbia/record/archives A Bing Crosby Collection vol. 2/ Columbia/record/archives A Bing Crosby Collection vol. 3/ Columbia/record/archives A Bridge Too Far soundtrack/ United Artists/record/archives A Collector’s Porgy and Bess/ RCA/ record/archives A Collector’s Showboat/ RCA/ record/archives A Christmas Sing with Bing, Around the World/Decca/record/archives A Christmas Sing with Bing, Around the World/MCA/record/archives A Chorus Line soundtrack/ Columbia/ record/ archives 2 A Golden Encore/ Columbia/ record/archives A Legendary Performer Series ( -

A Portrait of Tommy Dorsey

A PORTRAIT OF TOMMY DORSEY Prepared by Dennis M. Spragg Glenn Miller Archive Updated April 21, 2015 1 THE TALENTED AND TEMPERAMENTAL TD Although he celebrated his birthday as November 19, 1905, according to Schuylkill County records, Thomas Francis “Tommy” Dorsey, Jr. was born November 27, 1905 in Mahanoy Plane, a small town outside Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, the second son of Thomas Francis “Pop” Dorsey (born 1872) and Theresa “Tess” Langton (married 1901), Americans of Irish ancestry. Their firstborn son was James Francis “Jimmy” Dorsey, born February 29, 1904. The Dorsey couple bore two additional offspring, Mary, born 1907 and Edward, born 1911. Edward only lived to the age of three. Shenandoah was located in the heart of Pennsylvania coal country. Coal miner Pop Dorsey was once quoted as saying; “I would do anything to keep my sons out of the mines”. The Dorsey parents were interested in music and musically inclined. They saw music as a path for their sons to escape what they considered the “dead-end” future of coal mining. Pop and Tess Dorsey instilled a love of music in their sons. The father favored the cornet as an instrument and his sons fought over who would play it better. Ultimately, Jimmy Dorsey would gravitate to reed instruments and Tommy Dorsey to brass instruments. As children, the sons played in local parades and concerts. As they grew into adolescence, the brothers took nonmusical jobs to supplement the Dorsey family income. Young Tommy worked as a delivery boy. In 1920, the family moved to Lansford, Pennsylvania, where Pop Dorsey became leader of the municipal band and a music teacher. -

1403. I'm Getting Sentimental Over

1403. I’m Getting Sentimental Over You Backgrounds Of S. Radic Tommy Dorsey (905-1956/) was a US-American jazz musician (trombonist and trumpeter) who, together with his brother Jimmy Dorsey, founded Dorsey's Novelty Six in Shenandoah in the 1920s; they also played with the California Ramblers and the studio band The Little Ramblers. In New York, the two brothers initially went their separate ways; Tommy Dorsey played in Paul Whiteman's orchestra from 1927 to 1928, among other things. From 1934 to 1935, together with his brother, he Yamaha Tyros 5 By Rico led the very successful Dorsey Brother Band, in which successful band leaders such as Glenn Miller and Bob Crosby were later active as musicians. In 1935 Tommy founded his own Big Band, which became one of the most popular and successful orchestras of the Big Band The Midi editing proved to be relatively "difficult". The era. Stylistically situated between dance music and solo sound with trombone is still good - but the fully jazz, Dorsey featured such well-known jazz musicians written bag band improvisation is not easy! After a lot of of the time as Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Charlie Shavers, experimentation, I recorded the improvisation with the Bunny Berigan and Buddy DeFranco. Arrangers for Trombone movement of my Wersi-Pegasus. Here there Dorsey included Sy Oliver and Paul Weston, singers are two playing solutions: a) the very good note readers Jack Leonard, Frank Sinatra, Edythe Wright, Connie can of course play the complete set with the right hand Haines and Jo Stafford. One of his greatest hits was I'll b) the less experienced could also use the so-called Never Smile Again with Sinatra 1940, which he also AOC circuit and only play the monophonic melody, which sang in the musical Las Vegas Nights (1941). -

Frank Sinatra Them from a Reel-To-Reel Tape Or Tapes

Thanks to Dave for sharing the tracks on the net. Dave noted: More I Remember Tommy Sessions is a more thorough version of the May 3 sessions, compiled from several CDs I received in trade from a collector who said he transferred Frank Sinatra them from a reel-to-reel tape or tapes. Sound quality is nearly as good as “Inside More I Remember Tommy Sessions Tommy.” If you have “Inside Tommy,” you already have most of what’s here. So what does that leave? More session chatter, false starts, partial runthroughs, et., but no complete alternate takes that aren’t already on “Inside Tommy.” Disc 1 18. take 1 (alternate take) 2:57 The One I Love Belongs to Somebody Else 19. session chatter 2:43 01. session chatter 2:19 20. take 2 (false start) 0:28 02. partial runthrough 1:10 21. take 3 (false start) 0:42 03. session chatter 1:04 22. take 4 (false start) 0:18 04. partial runthrough 1:12 23. take 5 (alternate take) 2:57 05. session chatter 0:58 24. take 6 (tune up only) 2:13 06. partial runthrough 1:10 25. take 7 (alternate take) 2:44 07. session chatter 2:40 26. playback and session chatter 5:24 08. take 1 (incomplete take) 1:40 27. take 8 (false start) 0:17 09. session chatter 3:54 28. take 9 (false start) 1:03 10. take 2 (alternate take) 2:46 29. take 10 (false start - 11. session chatter 2:56 deliberate foul-up) 0:28 30. -

Frank Sinatra

Thanks to the person who shared these tracks on chanting tongue-in-cheek responses to the the net in 2007. lyric delivered by Lawrence’s replacement, young Frank Sinatra. Uploader’s notes: Frank Sinatra When Sinatra and Oliver tackled “The One I Inside I Remember Tommy: The Sessions More session excerpts, this time for I REMEMBER Love” in 1961, the conventional thing to do TOMMY. As always, it’s a mixed bag of alternate would have been to dispense with the band takes, incomplete takes, false starts, session chants altogether and perhaps replace them chatter, etc, plus a single spoken line for a with instrumental riffs - which, in fact, is what promotional bit of some kind. To the best of Sinatra did when he subsequently performed my knowledge, none of the material has been the song live (see the VEGAS box set for one released commercially. example). I’ve deliberately refrained from commenting on However, whether for old times’ sake or the music in my previous torrent descriptions, maybe just for the fun of it, Sinatra and Oliver as the music generally speaks for itself, but couldn’t resist taking a different approach, let me offer one historical note here for the so in the 1961 version, it’s Oliver himself one sake of relative newcomers. This album marks hears reprising (that word again!) the original, the reunion of Sinatra with one of the most light-hearted band chant lyrics (which he important arrangers from his formative years, himself may have dreamed up) in response to Melvin James “Sy” Oliver. -

The Chart Book – Albums the NME Album Charts

The Chart Book – Albums The NME Album Charts Volume 1 - 1962-1969 Compiled by Lonnie Readioff Contents Introduction Introduction ............................................................................................. 2 The New Musical Express may have begun the Singles chart (in 1952), but they where the last to Chart Milestones ...................................................................................... 3 the party in terms of creating an Album chart, only starting a Top 10 in 1962. Even then, albums would still chart on the main Singles chart, when sales we’re sufficiently large (Noticeably the The Artist Section ..................................................................................... 4 Beatles and the Rolling Stones achieved this). Having said this though, NME was sampling a Analysis Section ....................................................................................... 71 larger array of shops than the chart now considered the Official one fo the 1960’s, and so this Most Weeks On Chart By Artist ........................................................... 72 chart – together with Melody Maker – are equally merits of the position of “National” chart for Most Weeks On Chart By Year ............................................................ 74 the 1960’s. Most Weeks On Chart By Record ........................................................ 77 The small chart size here was simply all that NME decided to produce, and indeed it would be The Number 1’s ....................................................................................... -

DSN 37305 2016 Triplcate Sessions

37305 Studio C Capitol Recording Studios Los Angeles, California February 2016 Triplicate recording sessions produced by Jack Frost. 1. I Guess I'll Have To Change My Plan (Arthur Schwartz & Howard Dietz) 2. The September Of My Years (Jimmy van Heusen & Sammy Cahn) 3. I Could Have Told You (Jimmy van Heusen & Carl Sigman) 4. Once Upon A Time (Charles Strouse & Lee Adams) 5. Stormy Weather (Harold Arlen & Ted Koehler) 6. This Nearly Was Mine (Richard Rodgers & Oscar Hammerstein II) 7. That Old Feeling (Sammy Fain & Lew Brown) 8. It Gets Lonely Early (Jimmy van Heusen & Sammy Cahn) 9. My One And Only Love (Guy Wood & Robert Mellin) 10. Trade Winds (Cliff Friend & Charles Tobias) 11. Braggin' (Artie Manners & Jimmy Shirl) 12. As Time Goes By (Herman Humpfield) 13. Imagination (Jimmy van Heusen & Johnny Burke) 14. How Deep Is The Ocean (Irving Berlin) 15. P.S. I Love You (Gordon Jenkins & Johnny Mercer) 16. The Best Is Yet To Come (Cy Coleman & Carolyn Leigh) 17. But Beautiful (Jimmy van Heusen & Johnny Burke) 18. Here's That Rainy Day (Jimmy van Heusen & Johnny Burke) 19. Where Is The One (Alec Wilder & Ed Finckel) 20. There's A Flaw In My Flute (Jimmy van Heusen & Johnny Burke) 21. Day In Day Out (Rube Bloom & Johnny Mercer) 22. I Couldn't Sleep A Wink Last Night (Jimmy McHugh & Harold Adamson) 23. Sentimental Journey (Bud Green, Les Brown & Ben Homer) 24. Somewhere Along The Way (Kurt Adams & Sammy Gallup) 25. When The World Was Young (M. Philippe-Gerard & Johnny Mercer) 26. These Foolish Things (Jack Strachey, Harry Link & Holt Marvell) 27. -

BUY 3 and DELIVERY IS FREE Select the Album You Want and Copy/Paste the Whole Row Into a PM to Admin

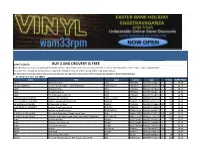

HOW TO ORDER: BUY 3 AND DELIVERY IS FREE Select the album you want and copy/paste the whole row into a PM to Admin. Prices are inclusive of VAT. P&P is £2.79 inc VAT (MyHermes courier) <2Kilos £3.50 for signed/tracked Once your PM is received we will contact you re payment via PayPal or BACS, all orders must be paid for in full before delivery. All orders taken over Easter will be delivered to you by Friday 21st April (last orders must be PM'd to Admin by midnight on Bank Holiday Monday) All albums are new and 180gm Artist Title Label Cat No Ean In Stock WAM PRICE 10 CC Bloody Tourists UMC 5705484 0602557054842 LP 12 17.39 10.000 MANIACS In The City Of Angels - 1993 Broadcast PARACHUTE PARA037LP 0803341505629 2LP 3 16.79 10CC How Dare You UMC 5705482 0602557054828 LP 19 16.79 10CC Deceptive Bends UMC 5705481 0602557054811 LP 6 16.79 10CC The Original Soundtrack UMC 5705483 0602557054835 LP 3 16.79 13TH FLOOR ELEVATOR Rockius Of Levitatum VINYL LOVERS 901233 0889397901233 LP 207 10.19 13TH FLOOR ELEVATORS Easter Everywhere Gold Vinyl CHARLY CHARLYL197 0803415819713 LP 118 18.59 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 Seconds To Mars VIRGIN 4799365 0602547993656 2LP 24 25.19 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Sounds Good Feels Good CAPITOL 4753191 0602547531919 LP 2 17.39 68 In Humour And Sadness EONE MUSIC EOMLP9436 0099923943617 LP 1 13.98 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST We Got It From Here Thank You 4 Your RCA 88985377871 0889853778713 2LP 143 17.39 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST People's Instinctive Travels And The Paths Of Rhythm SONY MUSIC 88875172371 0888751723719 2LP 118 14.99 A-HA -

37305 Studio C Capitol Recording Studios Los Angeles, California February 2016

37305 Studio C Capitol Recording Studios Los Angeles, California February 2016 Triplicate recording sessions produced by Jack Frost. 1. I Guess I'll Have To Change My Plan (Arthur Schwartz & Howard Dietz) 2. The September Of My Years (Jimmy van Heusen & Sammy Cahn) 3. I Could Have Told You (Jimmy van Heusen & Carl Sigman) 4. Once Upon A Time (Charles Strouse & Lee Adams) 5. Stormy Weather (Harold Arlen & Ted Koehler) 6. This Nearly Was Mine (Richard Rodgers & Oscar Hammerstein II) 7. That Old Feeling (Sammy Fain & Lew Brown) 8. It Gets Lonely Early (Jimmy van Heusen & Sammy Cahn) 9. My One And Only Love (Guy Wood & Robert Mellin) 10. Trade Winds (Cliff Friend & Charles Tobias) 11. Braggin' (Artie Manners & Jimmy Shirl) 12. As Time Goes By (Herman Humpfield) 13. Imagination (Jimmy van Heusen & Johnny Burke) 14. How Deep Is The Ocean (Irving Berlin) 15. P.S. I Love You (Gordon Jenkins & Johnny Mercer) 16. The Best Is Yet To Come (Cy Coleman & Carolyn Leigh) 17. But Beautiful (Jimmy van Heusen & Johnny Burke) 18. Here's That Rainy Day (Jimmy van Heusen & Johnny Burke) 19. Where Is The One (Alec Wilder & Ed Finckel) 20. There's A Flaw In My Flute (Jimmy van Heusen & Johnny Burke) 21. Day In Day Out (Rube Bloom & Johnny Mercer) 22. I Couldn't Sleep A Wink Last Night (Jimmy McHugh & Harold Adamson) 23. Sentimental Journey (Bud Green, Les Brown & Ben Homer) 24. Somewhere Along The Way (Kurt Adams & Sammy Gallup) 25. When The World Was Young (M. Philippe-Gerard & Johnny Mercer) 26. These Foolish Things (Jack Strachey, Harry Link & Holt Marvell) 27.