In Hampton Roads? While Harrisonburg Had a 16-Year Value

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

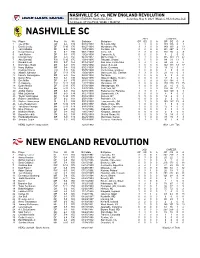

MLS Game Guide

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

Tribe Athletics

TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .................................................................................1 All-Time Roster ..................................................................................36 Quick Facts ............................................................................................2 Remembering Andy Crapol .............................................................36 Tradition ................................................................................................3 Jon Stewart .........................................................................................38 Albert-Daly Field .................................................................................4 International Trips .............................................................................39 Head Coach Chris Norris ....................................................................5 Tribe Athletics ...................................................................................40 Assistant Coaches .................................................................................7 The College .........................................................................................42 2009 Roster .............................................................................................8 W&M Administration .......................................................................44 Season Preview .....................................................................................9 Athletics Administration ..................................................................45 -

Soccer (Appendix 5)

Sports Facility Reports, Volume 6, Appendix 5 Soccer Major Indoor Soccer League (MISL) Team: Baltimore Blast Principal Owner: Edwin Hale, Sr. Arena: 1st Mariner Arena Date Built: 1962 UPDATE: 1st Mariner Bank is paying $750,000 annually for ten years for a naming rights deal that expires 2013. Team: California Cougars Principal Owner: John Thomas Arena: Stockton Events Center Date Built: End of 2005 or beginning of 2006 Facility Cost (millions): $64 - $70 M UPDATE: 2005-06 is the Cougars inaugural season. The Events Center was scheduled to be completed by October 2005, however due to weather complications it is not projected to be completed until January of 2006. Swinerton Builders is offering to speed up construction to complete the stadium by Dec 3, 2005, the ECHL’s Stockton Thunder scheduled first home game, if the city will pay $5 M for the added costs. Team: Chicago Storm Principal Owner: Viktor Jakovlevic Arena: UIC Pavilion Date Built: 1982 Facility Cost (millions): $10 M © Copyright 2005, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Team: Cleveland Force Principal Owner: North Coast Professional Sports, Ltd. Arena: Wolstein Center Date Built: 1991 Facility Cost (millions): $55 M UPDATE: Until January 2005, the Wolstein Center was known as the CSU Convocation Center. Because the Wolsteins donated $6.25 M to Cleveland State University, the University recognized their philanthropy by renaming the Center after them. Team: Kansas City Comets Principal Owner: Don and Patty Kincaid Arena: Kemper Arena Date Built: 1974 Facility Cost (millions): $22 M Facility Financing: $5.6 M came from general obligation bonds approved in 1954, R. -

Soccer Stadium

2005 SOC CER MEDIA INFORMATION ...............................................................................................................................2-3 Media Instructions ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Directions to Soccer Stadium ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Quick Facts ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Media List ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Travel Plans .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Why Monarchs? ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

2011 North American Soccer League Media Guide

2011 media guide Nasl.com 2011 NASL Media Guide Last Revision: November 7, 2011 Table of contents NASL Vision .............................................................................................. 1 QUICK FACTS About The North American Soccer League ......................................... 2 League Information The Commissioner .................................................................................. 3 Phone: (786) 728-8990 Board of Governors ................................................................................. 3 Fax: (786) 221-4873 Directors and Staff .................................................................................. 3 Website: www.nasl.com NASL Clubs ............................................................................................... 4 Mailing Address Team Markets and Roster Breakdown ................................................ 5 North American Soccer League Atlanta Silverbacks ................................................................................. 6 501 Brickell Key Drive, Suite 405 Atlanta Silverbacks Roster .................................................................... 7 Miami, FL 33131 Carolina RailHawks ................................................................................. 8 Media Contact Carolina RailHawks Roster .................................................................... 9 Kartik Krishnaiyer FC Edmonton ............................................................................................ 10 Director of Communications & Public -

Record Vs. Opponents

RECORD VS. OPPONENTS SIX CAA CHAMPIONSHIPS • 12 NCAA TOURNAMENT APPEARANCES • 436 ALL-TIME VICTORIES • 12 ALL-AMERICANS • 75 ALL-CAA SELECTIONS • FOUR CAA PLAYERS OF THE YEAR • 46 NSCAA ALL-REGION SELECTIONS Goals Meetings Goals Meetings Opponent G Overall Home Away N’tral Pct. WM Opp. First Last Opponent G Overall Home Away N’tral Pct. WM Opp. First Last Adelphi 1 1-0-0 0-0-0 0-0-0 1-0-0 1.000 4 0 9/24/95 9/24/95 Maryland 7 3-4-0 1-0-0 2-3-0 0-1-0 .429 6 7 12/1/96 9/27/05 Air Force 1 1-0-0 0-0-0 0-0-0 1-0-0 1.000 2 0 9/25/94 9/25/94 UMBC 4 3-0-1 1-0-1 2-0-0 0-0-0 .875 8 1 9/21/90 11/7/02 Akron 3 0-3-0 0-0-0 0-1-0 0-2-0 .000 0 4 11/8/87 9/30/90 Mary Washington 2 2-0-0 1-0-0 1-0-0 0-0-0 1.000 6 1 9/4/85 9/3/86 Alabama A&M 2 1-1-0 1-0-0 0-0-0 0-1-0 .500 3 3 1980 9/18/93 Methodist 2 2-0-0 2-0-0 0-0-0 0-0-0 1.000 7 2 9/20/73 11/9/85 Alderson-Broaddus 2 1-1-0 0-1-0 1-0-0 0-0-0 .500 2 3 10/9/83 9/8/84 Miami (Ohio) 1 1-0-0 1-0-0 0-0-0 0-0-0 1.000 5 0 9/5/97 9/5/97 American 34 20-10-4 10-3-2 7-6-2 3-1-0 .647 61 41 1969 9/26/04 Monmouth 1 1-0-0 0-0-0 0-0-0 0-0-0 1.000 2 1 10/24/98 10/24/98 Appalachian State 5 0-4-1 0-2-1 0-1-0 0-1-0 .100 3 10 11/11/72 8/31/02 Mt. -

Part 4: the State of Soccer in Hampton Roads

The State Of Soccer In Hampton Roads THE STATE OF SOCCER IN HAMPTON ROADS Soccer isn’t the same as Bach or Buddhism. But it is often more deeply felt than religion, and just as much a part of the community’s fabric, a repository of traditions. – Franklin Foer, “How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization” t has been called “The Beautiful Game” (a nickname popularized by Pelé, the legendary Brazilian footballer) and “The World’s Game.” With apologies to soccer purists, the second name is probably more accurate. The scope and size of the sport of soccer – football to most of the world – are undeniably large. Soccer is played by the young and old, men and women, believers of different (or no) faiths, the poor and rich, from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. It is becoming increasingly popular in the United States, ranking fourth among all sports in terms of popularity in a recent Gallup survey.1 While American football dominated the list Iof favorite sports in the U.S., with 37 percent of respondents saying it was their favorite sport to watch, soccer, at 7 percent, was only 2 percentage points behind baseball (9 percent) and 4 percentage points behind basketball (11 percent) in terms of popularity. To say that soccer has an avid global fan base would be an understatement.1 record four championships, including the 2-0 victory over the Netherlands The 2018 World Cup in Russia drew an estimated 3.6 billion viewers, nearly in the finals earlier this year. The 5-2 victory over Japan in the 2015 FIFA half of the world’s population.2 The top professional soccer clubs are among Women’s World Cup final was the most-watched soccer match in U.S. -

Organization and Programs ™ 02

™ ™ 20181 TECHNICAL TRAINING Organization and Programs ™ 02 TECHNICAL TRAINING Mission Statement Our mission at Own Touch is to In order to transform our mission into The Own create an atmosphere where Touch Way, our focus areas are as follows: soccer players are transformed into technically proficient, • High quality, professional technical training skillfully advanced, passionate • Measurable development of soccer skills and confident athletes. We foster a learning environment • Increased experience that challenges players to perform, yet embraces mistakes, • Good sportsmanship which is a natural and necessary • Strong work ethic part of development. Our programs reflect our philosophy • A fun, exciting, positive, supportive, and of growing the love of the safe environment beautiful game from the inside • A comprehensive age-appropriate out, as a family. training program Excellence is desired. • A peer learning environment where players Commitment is required. work and learn from each other ™ 03 TECHNICAL TRAINING Philosophy Soccer players throughout most of world, grew up playing soccer in the streets - learning finesse, control and TOUCH – all skills that improve confidence and performance. Here in America, we grow up playing on teams. Teams must focus on team tactics to win games. Own Touch turns that philosophy inside out and focuses on individual development. When players learn to develop their touch, they learn precision, which leads to keeping possession of the ball, which leads to opportunities to score, and ultimately . to win. Here at Own Touch, we are dedicated to helping our trainees master individual technical skills that will become ingrained in their athletic memory. ™ 04 TECHNICAL TRAINING Technical Vision Technical Vision from Director Bob Jenkins Our goal is to train players to be as efficient as possible with technical ability and movement. -

Program Guide

™ ™ 20181 TECHNICAL TRAINING Organization and Programs ™ 02 TECHNICAL TRAINING Mission Statement Our mission at Own Touch is to In order to transform our mission into The Own create an atmosphere where To u c h Way , our focus areas are as follows: soccer players are transformed into technically proficient, • High quality, professional technical training skillfully advanced, passionate • Measurable development of soccer skills and confident athletes. We foster a learning environment • Increased experience that challenges players to perform, yet embraces mistakes, • Good sportsmanship which is a natural and necessary • Strong work ethic part of development. Our programs reflect our philosophy • A fun, exciting, positive, supportive, and of growing the love of the safe environment beautiful game from the inside • A comprehensive age-appropriate out, as a family. training program Excellence is desired. • A peer learning environment where players Commitment is required. work and learn from each other ™ 03 TECHNICAL TRAINING Philosophy Soccer players throughout most of world, grew up playing soccer in the streets - learning finesse, control and TOUCH – all skills that improve confidence and performance. Here in America, we grow up playing on teams. Teams must focus on team tactics to win games. Own Touch turns that philosophy inside out and focuses on individual development. When players learn to develop their touch, they learn precision, which leads to keeping possession of the ball, which leads to opportunities to score, and ultimately . to win. Here at Own Touch, we are dedicated to helping our trainees master individual technical skills that will become ingrained in their athletic memory. ™ 04 TECHNICAL TRAINING Technical Vision Technical Vision from Director Bob Jenkins Our goal is to train players to be as efficient as possible with technical ability and movement. -

Mscguidelow.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Season Preview Page 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2008 SEASON INFORMATION Table of Contents -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Quick Facts ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Tradition -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Albert-Daly Field --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 Head Coach Chris Norris ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Assistant Coaches ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 Season Preview ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------10 The Tribe ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------12 2007 SEASON INFORMATION 2007 Season Review --------------------------------------------------------------------------------22 Staff 2007 Statistics -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------23 Page 6 RECORD BOOK AND HISTORY Single-Season Records -----------------------------------------------------------------------------24 Career Records ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------25 Team Honors -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------26 Honors and Awards ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------27 -

08 MS Media Guide.Indd

BIG SOUTH CHAMPIONS 2008 SEASON 2007 BIG SOUTH CHAMPIONS A GOAL REALIZED; THE FLAMES CAPTURE PROGRAM’S FIRST-EVER BIG SOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP Ever since joining the Big South Conference, neither team could tally the contest’s fi rst goal, the Liberty Flames men’s soccer program has as the match went to intermission, 0-0. set a goal of winning a conference champion- Despite carrying play by outshooti ng the ship. And despite several championship ap- Bulldogs 9-1, the Flames could not get the up- pearances and being a perennial contender per hand. A shot by midfi elder Josh Boateng in in the Big South, the soccer season always the opening fi ve mintues hit the crossbar and seemed to come to an end without a confer- the UNC Asheville goalkeeper turned back two ence ti tle. other att empts to keep the contest scoreless. However, the 2007 campaign had turned In the second half, the defensive struggle out to be a banner year for Head Coach Jeff conti nued with neither team att empti ng a shot Alder’s program during the regular season. through the fi rst 18 minutes. At 63:02, the For the fi rst ti me since 2002, the Flames had half’s fi rst shot by UNC Asheville’s Scott Szy- reached double-digits in wins with a 10-4-2 manski found the left corner of the Liberty net, record. Behind an outstanding defensive ef- and the Flames found themselves down, 1-0. fort, Liberty had shut out eight opponents to However, Liberty remained poised and con- place among the nati on’s elite in shutout per- ti nued to work its off ensive patt erns in search centage. -

Organization and Programs ™ 02

™ ™ 20181 TECHNICAL TRAINING Organization and Programs ™ 02 TECHNICAL TRAINING Mission Statement Our mission at Own Touch is to In order to transform our mission into The Own create an atmosphere where Touch Way, our focus areas are as follows: soccer players are transformed into technically proficient, • High quality, professional technical training skillfully advanced, passionate • Measurable development of soccer skills and confident athletes. We foster a learning environment • Increased experience that challenges players to perform, yet embraces mistakes, • Good sportsmanship which is a natural and necessary • Strong work ethic part of development. Our programs reflect our philosophy • A fun, exciting, positive, supportive, and of growing the love of the safe environment beautiful game from the inside • A comprehensive age-appropriate out, as a family. training program Excellence is desired. • A peer learning environment where players Commitment is required. work and learn from each other ™ 03 TECHNICAL TRAINING Philosophy Soccer players throughout most of world, grew up playing soccer in the streets - learning finesse, control and TOUCH – all skills that improve confidence and performance. Here in America, we grow up playing on teams. Teams must focus on team tactics to win games. Own Touch turns that philosophy inside out and focuses on individual development. When players learn to develop their touch, they learn precision, which leads to keeping possession of the ball, which leads to opportunities to score, and ultimately . to win. Here at Own Touch, we are dedicated to helping our trainees master individual technical skills that will become ingrained in their athletic memory. ™ 04 TECHNICAL TRAINING Technical Vision Technical Vision from Director Bob Jenkins Our goal is to train players to be as efficient as possible with technical ability and movement.