Building a Better Mousetrap: Patenting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doc Adams Base Ball

For Immediate Release: Contact: [email protected] Doc Adams’ “Laws of Baseball” Sells for $3.26 Million at Auction Connecticut Legislator and Bank President’s Document Gets Record Price A rare piece of baseball history sold on Sunday, April 24th for a price far exceeding what experts predicted. “The Laws of Baseball”, an 1857 document, was handwritten by Daniel Lucius “Doc” Adams. The “Laws of Baseball” was purchased for $3.26 million, making the item the highest-priced baseball document ever sold. SCP Auctions, which managed the sale, reported that the new owner wishes to remain anonymous. The manuscript details many of the fundamental aspects of baseball as written by Adams and illustrates the influence and contributions he made to the game. At the time the document was written, Adams was President of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York City and chairman of the rules committee of the convention of New York and Brooklyn base ball clubs. In “The Laws of Baseball” Adams set the bases at 90 feet, established 9 players per side and 9 innings of play – all innovations at the time. This sale places the “Laws” as the third most expensive piece of sports history, behind a 1920 Yankees Babe Ruth jersey at $4.4 million and the James Naismith Rules of Basketball at $4.3 million. The Adams legacy has been garnering significant attention recently. SABR (Society for American Baseball Research) named Adams the 19th Century Overlooked Legend for 2014. His name was on the Pre-Integration Era Ballot for the Baseball Hall of Fame last year. -

Thesis 042813

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Utah: J. Willard Marriott Digital Library THE CREATION OF THE DOUBLEDAY MYTH by Matthew David Schoss A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History The University of Utah August 2013 Copyright © Matthew David Schoss 2013 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Matthew David Schoss has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Larry Gerlach , Chair 05/02/13 Date Approved Matthew Basso , Member 05/02/13 Date Approved Paul Reeve , Member 05/02/13 Date Approved and by Isabel Moreira , Chair of the Department of History and by Donna M. White, Interim Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT In 1908, a Special Base Ball Commission determined that baseball was invented by Abner Doubleday in 1839. The Commission, established to resolve a long-standing debate regarding the origins of baseball, relied on evidence provided by James Sullivan, a secretary working at Spalding Sporting Goods, owned by former player Albert Spalding. Sullivan solicited information from former players and fans, edited the information, and presented it to the Commission. One person’s allegation stood out above the rest; Abner Graves claimed that Abner Doubleday “invented” baseball sometime around 1839 in Cooperstown, New York. It was not true; baseball did not have an “inventor” and if it did, it was not Doubleday, who was at West Point during the time in question. -

A National Tradition

Baseball A National Tradition. by Phyllis McIntosh. “As American as baseball and apple pie” is a phrase Americans use to describe any ultimate symbol of life and culture in the United States. Baseball, long dubbed the national pastime, is such a symbol. It is first and foremost a beloved game played at some level in virtually every American town, on dusty sandlots and in gleaming billion-dollar stadiums. But it is also a cultural phenom- enon that has provided a host of colorful characters and cherished traditions. Most Americans can sing at least a few lines of the song “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” Generations of children have collected baseball cards with players’ pictures and statistics, the most valuable of which are now worth several million dollars. More than any other sport, baseball has reflected the best and worst of American society. Today, it also mirrors the nation’s increasing diversity, as countries that have embraced America’s favorite sport now send some of their best players to compete in the “big leagues” in the United States. Baseball is played on a Baseball’s Origins: after hitting a ball with a stick. Imported diamond-shaped field, a to the New World, these games evolved configuration set by the rules Truth and Tall Tale. for the game that were into American baseball. established in 1845. In the early days of baseball, it seemed Just a few years ago, a researcher dis- fitting that the national pastime had origi- covered what is believed to be the first nated on home soil. -

Baseball Cards

THE KNICKERBOCKER CLUB 0. THE KNICKERBOCKER CLUB - Story Preface 1. THE EARLY DAYS 2. THE KNICKERBOCKER CLUB 3. BASEBALL and the CIVIL WAR 4. FOR LOVE of the GAME 5. WOMEN PLAYERS in the 19TH CENTURY 6. THE COLOR LINE 7. EARLY BASEBALL PRINTS 8. BIRTH of TRADE CARDS 9. BIRTH of BASEBALL CARDS 10. A VALUABLE HOBBY The Knickerbocker Club played baseball at Hoboken's "Elysian Fields" on October 6, 1845. That game appears to be the first recorded by an American newspaper. This Currier & Ives lithograph, which is online via the Library of Congress, depicts the Elysian Fields. As the nineteenth century moved into its fourth decade, Alexander Cartwright wrote rules for the Knickerbockers, an amateur New York City baseball club. Those early rules (which were adopted on the 23rd of September, 1845) provide a bit of history (perhaps accurate, perhaps not) for the “Recently Invented Game of Base Ball.” For many years the games of Townball, Rounders and old Cat have been the sport of young boys. Recently, they have, in one form or another, been much enjoyed by gentlemen seeking wholesome American exercise. In 1845 Alexander Cartwright and other members of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York codified the unwritten rules of these boys games into one, and so made the game of Base Ball a sport worthy of attention by adults. We have little doubt but that this gentlemanly pastime will capture the interest and imagination of sportsman and spectator alike throughout this country. Within two weeks of adopting their rules, members of the Knickerbocker Club played an intra-squad game at the Elysian Fields (in Hoboken, New Jersey). -

MEDIA and LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS of LATINOS in BASEBALL and BASEBALL FICTION by MIHIR D. PAREKH Presented to the Faculty of T

MEDIA AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF LATINOS IN BASEBALL AND BASEBALL FICTION by MIHIR D. PAREKH Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2015 Copyright © by Mihir Parekh 2015 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks to my supervisor, Dr. William Arcé, whose knowledge and expertise in Latino studies were vital to this project. I would also like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. Timothy Morris and Dr. James Warren, for the assistance they provided at all levels of this undertaking. Their wealth of knowledge in the realm of sport literature was invaluable. To my family: the gratitude I have for what you all have provided me cannot be expressed on this page alone. Without your love, encouragement, and support, I would not be where I am today. Thank you for all you have sacrificed for me. April 22, 2015 iii Abstract MEDIA AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF LATINOS IN BASEBALL AND BASEBALL FICTION Mihir D. Parekh, MA The University of Texas at Arlington, 2015 Supervising Professors: William Arcé, Timothy Morris, James Warren The first chapter of this project looks at media representations of two Mexican- born baseball players—Fernando Valenzuela and Teodoro “Teddy” Higuera—pitchers who made their big league debuts in the 1980s and garnered significant attention due to their stellar play and ethnic backgrounds. Chapter one looks at U.S. media narratives of these Mexican baseball players and their focus on these foreign athletes’ bodies when presenting them the American public, arguing that 1980s U.S. -

Baseball News Clippings

! BASEBALL I I I NEWS CLIPPINGS I I I I I I I I I I I I I BASE-BALL I FIRST SAME PLAYED IN ELYSIAN FIELDS. I HDBOKEN, N. JT JUNE ^9f }R4$.* I DERIVED FROM GREEKS. I Baseball had its antecedents In a,ball throw- Ing game In ancient Greece where a statue was ereoted to Aristonious for his proficiency in the game. The English , I were the first to invent a ball game in which runs were scored and the winner decided by the larger number of runs. Cricket might have been the national sport in the United States if Gen, Abner Doubleday had not Invented the game of I baseball. In spite of the above statement it is*said that I Cartwright was the Johnny Appleseed of baseball, During the Winter of 1845-1846 he drew up the first known set of rules, as we know baseball today. On June 19, 1846, at I Hoboken, he staged (and played in) a game between the Knicker- bockers and the New Y-ork team. It was the first. nine-inning game. It was the first game with organized sides of nine men each. It was the first game to have a box score. It was the I first time that baseball was played on a square with 90-feet between bases. Cartwright did all those things. I In 1842 the Knickerbocker Baseball Club was the first of its kind to organize in New Xbrk, For three years, the Knickerbockers played among themselves, but by 1845 they I had developed a club team and were ready to meet all comers. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

First Look at the Checklist

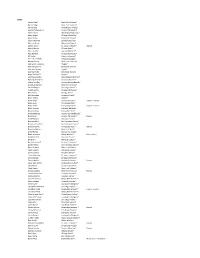

BASE Aaron Hicks New York Yankees® Aaron Judge New York Yankees® Aaron Nola Philadelphia Phillies® Adalberto Mondesi Kansas City Royals® Adam Eaton Washington Nationals® Adam Engel Chicago White Sox® Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® Adam Ottavino Colorado Rockies™ Addison Reed Minnesota Twins® Adolis Garcia St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie Albert Almora Chicago Cubs® Alex Colome Seattle Mariners™ Alex Gordon Kansas City Royals® All Smiles American League™ AL™ West Studs American League™ Always Sonny New York Yankees® Andrelton Simmons Angels® Andrew Cashner Baltimore Orioles® Andrew Heaney Angels® Andrew Miller Cleveland Indians® Angel Stadium™ Angels® Anthony Rendon Washington Nationals® Antonio Senzatela Colorado Rockies™ Archie Bradley Arizona Diamondbacks® Aroldis Chapman New York Yankees® Austin Hedges San Diego Padres™ Avisail Garcia Chicago White Sox® Ben Zobrist Chicago Cubs® Billy Hamilton Cincinnati Reds® Blake Parker Angels® Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ League Leaders Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ League Leaders Blake Treinen Oakland Athletics™ Boston's Boys Boston Red Sox® Brad Boxberger Arizona Diamondbacks® Brad Keller Kansas City Royals® Rookie Brad Peacock Houston Astros® Brandon Belt San Francisco Giants® Brandon Crawford San Francisco Giants® Brandon Lowe Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie Brandon Nimmo New York Mets® Brett Phillips kansas City Royals® Brian Anderson Miami Marlins® Future Stars Brian McCann Houston Astros® Bring It In National League™ Busch Stadium™ St. Louis Cardinals® Buster Posey San Francisco -

The History of Baseball the Rise of America and Its “National Game”

The History of Baseball The Rise of America and its “National Game” “Baseball, it is said, is only a game. True. And the Grand Canyon is only a hole in Arizona.” – George Will History 389-007 Dr. Ryan Swanson Contact: [email protected] Office hours: Monday 1:30-3pm, by appt. Robinson B 377D Baseball. America’s National Pastime. The thinking man’s and thinking woman’s sport. A rite of spring and ritual of fall. A game that explains the nation, or at least that’s what some have contended. ―Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America,‖ argued French historian Jacques Barzan, ―had better learn Baseball.‖ The game is at once simple, yet complex. And so is the interpretation of its history. In this course we will examine the development of the game of baseball as means of better understanding the United States. Baseball evidences many of the contradictions and conflicts inherent in American history—urban v. rural, capital v. labor, progress v. nostalgia, the ideals of the Bill of Rights v. the realities of racial segregation, to name a few. This is not a course where we will engage in baseball trivia, but rather a history course that uses baseball as its lens. Course Objectives 1. Analyze baseball’s rich primary resources 2. Understand the basic chronology of baseball history 3. Critique 3 secondary works 4. Interpret the rise and fall of baseball’s racial segregation 5. Write a thesis-driven, argumentative historical paper Structure The course will utilize a combination of lectures and discussion sessions. -

The Ongoing Fable of Baseball by MARK Mcguire

NEW Y ORK Volume 2 • Number 4 • Spring 2003 8 Americans revere Cooperstown and Abner Doubleday as icons of baseball, although historical evidence leaves both birthplace and inventor in doubt The Ongoing Fable of Baseball BY MARK McGUIRE he National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York contains: •2.6 million library documents • 30,000 “three-dimensional” artifacts, Tincluding 6,251 balls, 447 gloves, Babe Ruth’s bowling ball, and Christy Mathewson’s piano •half a million photographs •more than 15,000 files on every Major Leaguer who ever played • 12,000 hours of recordings • 135,000 baseball cards • one pervasive, massive, enduring myth Hall of Famer Hughie Jennings For in this mecca of the sport, history and historical fancy co-exist. Undoubtedly, the village that’s synonymous with baseball’s glory is the home of baseball. It’s just not baseball’s hometown. NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY LIBRARY BASEBALL HALL OF FAME NATIONAL NEW YORK archives • SPRING 2003 9 Many kids first learning about the game’s lore hear that baseball was invented by Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown. But most histori- ans––and even the Hall––acknowledge that the Doubleday tale is a myth concocted with the thinnest of evidence early in the twentieth century, a yarn promoted by a sporting goods Abner Doubleday fired the first magnate determined to prove that the game Union shot of the Civil War at was a uniquely American invention. Fort Sumter. And Doubleday was truly a unique American. NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY A West Point graduate, he fought in the Mexican War in 1846–48. -

Spalding's Official Base Ball Guide, 1910

Library of Congress Spalding's official base ball guide, 1910 SPALDING'S OFFICIAL BASE BALL GUIDE 1910 ,3I ^, Spalding's Athletic Library - FREDERICK R. TOOMBS A well known authority on skating, rowing. boxing, racquets, and other athletic sports; was sporting editor of American Press Asso- ciation, New York; dramatic editor; is a law- yer and has served several terms as a member of Assembly of the Legislature of the State of New York; has written several novels and historical works. R. L. WELCH A resident of Chicago; the popularity of indoor base ball is chiefly due to his efforts; a player himself of no mean ability; a first- class organizer; he has followed the game of indoor base ball from its inception. DR. HENRY S. ANDERSON Has been connected with Yale University for years and is a recognized authority on gymnastics; is admitted to be one of the lead- ing authorities in America on gymnastic sub- jects; is the author of many books on physical training. CHARLES M. DANIELS Just the man to write an authoritative book on swimming; the fastest swimmer the world has ever known; member New York Athletic Club swimming team and an Olym- pic champion at Athens in 1906 and London, 1908. In his book on Swimming, Champion Daniels describes just the methods one must use to become an expert swimmer. GUSTAVE BOJUS Mr. Bojus is most thoroughly qualified to write intelligently on all subjects pertaining to gymnastics and athletics; in his day one of America's most famous amateur athletes; has competed Spalding's official base ball guide, 1910 http://www.loc.gov/resource/spalding.00155 Library of Congress successfully in gymnastics and many other sports for the New York Turn Verein; for twenty years he has been prom- inent in teaching gymnastics and athletics; was responsible for the famous gymnastic championship teams of Columbia University; now with the Jersey City high schools. -

Daniel Lucius “Doc” Adams, Md

DANIEL LUCIUS “DOC” ADAMS, MD 1814: Born , Mont Vernon, NH 1835: Graduated from Yale 1831-1833: Attended Amherst College, 1838: Graduated from Harvard Medical transferred to Yale in 1833 School. Practiced medicine with his father in NH, later Boston 1839: Moved to New York City, set up his medical practice and became actively involved in treating the poor. Began playing base ball 1845: Joined the newly formed New York Knickerbockers Base Ball Club 1839-1862: 1. Played with the New York Base Ball Club and the New York Knickerbockers. (1B, 2B, 3B, SS and umpire) The latter was one of the first organized baseball teams which played under a set of rules similar to the game today. June 19, 1846: 2. Played in the “first” officially recognized baseball game at the Elysian Fields, Hoboken, New Jersey 1846: 3. Elected Vice-President of the Knickerbockers, and President in ’47, ’48, ’49, ’56, ’57 and ’61, and served as a director in other years. 1849/50: 4. Credited with creating the position of shortstop and was the first to occupy it. 5. Personally made the balls and oversaw the making of bats, not only for the Knickerbockers but for other NYC clubs, to standardize the game’s equipment. 1848, 1853: 6. Elected presiding officer of the first conventions and Rules Committees to standardize the rules of the game. 1857/58: 7. Elected presiding officer of the convention of twelve New York teams: the National Association of Base Ball Players was formed. • The distance between bases was fixed at 90 feet and pitcher’s base to home at 45 feet.