A History of the Coleorton Railway and the Charnwood Forest Canal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rails: History and the Indispensable Connection with the Steel Industry

December 02, 2020 Rails: history and the indispensable connection with the steel industry In 1895, a steel palm tree appeared in Yuzovka (now Donetsk). It was forged by Aleksey Mertsalov, a forging operator at the local iron and steel plant. Five years later, at an international industrial exhibition in Paris, it was awarded the Grand Prix. Over time, it became a symbol of Donetsk and was even displayed on the coat-of-arms of Donetsk region. But few people know that this tree, exotic for our latitudes, was forged not just from a piece of iron, but from a whole steel rail. After all, steel for rails was one of the main types of products that were produced at the enterprise. Mertsalov’s palm tree has become more than a symbol of one industrial region in modern Ukraine; it is also a link between the steel industry and railways, which have been developing side-by-side for the past 200 years. Iron rails: history and development The first rails appeared in mining in the 16th century. However, these were primitive wooden structures along which ore cars moved. In the second half of the 17th century, the British industrialists of Derby, who owned the factories in Colbrookdale (today this village is known as part of the Ironbridge Gorge along the River Severn), also began to use wooden railroads. Steel began to be used for rails a little later. Over time, wooden structures were replaced with iron plates. This significantly increased the volume of transported goods using horse traction. Near the end of the century, in the coal mines of Sheffield, the wood began to be strengthened with iron strips and squares. -

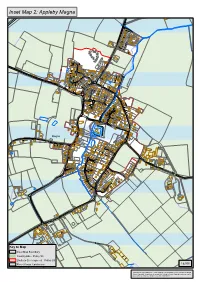

Inset Map 2: Appleby Magna

Inset Map 2: Appleby Magna Magna Key to Map Inset Map Boundary Countryside - Policy S3 Limits to Development - Policy S3 River Mease Catchment 1:6,000 Reproduction from Ordnance 1:1250 mapping with permission of the Controller of HMSO Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings Licence No: 100019329 Inset Map 3: Ashby de la Zouch Key to Map NWLDC Boundary Inset Map Boundary Countryside - Policy S2 Limits to Development - Policy S2 Housing Provision planning permissions - Policy H1 Housing Provision resolutions - Policy H2 Ec2(1) Housing Provision new allocations - Policy H3 Employment Provision Permissions - Policy Ec1 H3a Employment Allocations new allocations - Policy Ec2 Primary Employment Areas - Policy Ec3 EMA Safeguarded Area - Policy Ec5 Ec3 Leicester to Burton rail line - Policy IF5 River Mease Catchment H3a Ec2(1) National Forest - Policy En3 Sports Field H1b Ec3 H1a Ec3 Inset Map 4 Ec1a ASHBY-DE-LA-ZOUCH 1:9,000 Reproduction from Ordnance 1:1250 mapping with permission of the Controller of HMSO Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings Licence No: 100019329 Willesley W ill e s ley P ar k Inset Map 8: Castle Donington Trent Valley Washlands Ec3 CASTLE Inset Map 9 H1c Melbourne Paklands Key to Map Reproduction from Ordnance 1:1250 mapping with permission of the Controller of HMSO Crown Copyright. 1:11,000 Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead Inset Map Boundary -

Lyndale Cottage, 31 Worthington Lane, Newbold Coleorton, Leicestershire, LE67 8PJ

Lyndale Cottage, 31 Worthington Lane, Newbold Coleorton, Leicestershire, LE67 8PJ Lyndale Cottage, 31 Worthington Lane, Newbold Coleorton, Leicestershire, LE67 8PJ Guide Price: £400,000 Extending to approximately 2000 sqft, a substantial four/five bedroom period cottage dating back to 1750. The Cottage in this village setting boasts a large 26ft dual aspect living room with log burner, generous open plan living kitchen, separate utility, pantry and cloakroom together with study and vaulted conservatory. To the first floor there are five bedrooms including master with contemporary en-suite and a fully re-furbished family bathroom. Outside, cottage gardens and a detached outbuilding suitable for a workshop. Features • Substantial family cottage • Five bedrooms, two bathrooms • Large 26ft living room • Generous living kitchen and study • Cottage gardens • Potential workshop • Delightful village setting • Ideal for commuters Location The village boasts a local village pub, Primary School and excellent footpath links to the National Forest. Set approximately three miles east of Ashby town centre (a small market town offering a range of local facilities and amenities), Newbold Coleorton lies close to the A42 dual carriageway with excellent road links to both the M1 motorway corridor (with East Midland conurbations beyond) and west to Birmingham. The rolling hills of North West Leicestershire and the adjoining villages of Peggs Green, Coleorton, Worthington and Griffydam offer excellent countryside with National Forest Plantations linked by public footpaths, public houses and nearby amenities and facilities. Travelling Distances: Leicester - 16.2 miles Derby - 17.2 miles Ashby de la Zouch - 4.7miles East Midlands Airport - 6.3 miles Accommodation Details - Ground Floor side gardens. -

Railway and Canal Historical Society Early Railway

RAILWAY AND CANAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY EARLY RAILWAY GROUP Occasional Paper 255 [ editor’s note: this paper is in reply to a query in Circular 37: “Charnwood Forest Canal tramway rails. The following enquiry is from Michael Gillingham via Wendy Freer: I wondered if you would be able to give me any leads on some of my investigations re the cast iron fish belly rails that are said to have been used on the tram road at Nanpantan. It is said that this was the first time edge rails were used! …” And see the related notes on the Kidderminster rail in Circular 37 and Railway & Canal Historical Society, Early Railway Group Occasional Paper [ERG OP]256, Rowan Patel, ‘Butterley Company Edge Rails: their use at Belvoir Castle and elsewhere’. ____________________________ The Leicester Navigationʼs Forest Line: a myth debunked Michael Lewis One of the least successful projects of the Canal Mania was the Charnwood Forest Line of the Leicester Navigation, which was intended to bring coal from pits around Coleorton to the main waterway at Loughborough. It was to be a hybrid transport route, with railways on the steeper stretches at each end but a canal on the level central portion. “The bodies of the Trams were made to lift off, or to be placed on their wheels, by means of cranes” and stowed in canal boats1: an early instance of containerisation. And not only was the system a fiasco, but there are few early railways whose story has been more befogged by misinformation and misinterpretation. Although the general outline was elucidated in an invaluable paper of 19552, until recently the nature of the rails has remained obscure, for none has been found in the field. -

Chairman's Update

LEICESTERSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL HIGHWAYS FORUM FOR NORTH WEST LEICESTERSHIRE 14TH JULY 2016 CHAIRMAN’S UPDATE REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR OF ENVIRONMENT AND TRANSPORT T5 Street Lighting Transformation Project 2016/17 1. Leicestershire Highways is upgrading the County Councils street lighting stock to LEDs, in order to make substantial savings in energy, carbon and maintenance costs. Leicestershire County Council will be carrying out over 68,000 street light replacements across the county and are programmed to complete all installations within the next 3 years. Initially we are concentrating on the low level street lights (5 & 6m columns) which are mainly in residential areas with the high level installations (6m & above) due to commence from October this year. 2. The first low level installations were successfully carried out in Shepshed, as programmed in March this year, before a full roll-out of four installation teams started work in Loughborough, Hugglescote and Whitwick throughout April and into May. The project is progressing well and is on programme both in time and budget. 3. Details of the full construction programme for the project are being prepared in a suitable format to share with Members and residents and we anticipate this information will be available by the end of June. 4. The table below provides the implementation programme to the end of the current financial year. 2016 May Whitwick, Loughborough, Coalville June Coalville cont., Oadby & Wigston July Ravenstone, Packington, Coleorton, Ellistown, Swannington, Ibstock, Anstey, -

The Myth of the Standard Gauge

The Myth of the Standard Guage: Rail Guage Choice in Australia, 1850-1901 Author Mills, John Ayres Published 2007 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith Business School DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/426 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366364 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au THE MYTH OF THE STANDARD GAUGE: RAIL GAUGE CHOICE IN AUSTRALIA, 1850 – 1901 JOHN AYRES MILLS B.A.(Syd.), M.Prof.Econ. (U.Qld.) DEPARTMENT OF ACCOUNTING, FINANCE & ECONOMICS GRIFFITH BUSINESS SCHOOL GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2006 ii ABSTRACT This thesis describes the rail gauge decision-making processes of the Australian colonies in the period 1850 – 1901. Federation in 1901 delivered a national system of railways to Australia but not a national railway system. Thus the so-called “standard” gauge of 4ft. 8½in. had not become the standard in Australia at Federation in 1901, and has still not. It was found that previous studies did not examine cause and effect in the making of rail gauge choices. This study has done so, and found that rail gauge choice decisions in the period 1850 to 1901 were not merely one-off events. Rather, those choices were part of a search over fifty years by government representatives seeking colonial identity/autonomy and/or platforms for election/re-election. Consistent with this interpretation of the history of rail gauge choice in the Australian colonies, no case was found where rail gauge choice was a function of the disciplined search for the best value-for-money option. -

A Light in the Darkness •Fi the Taper Burns of Donington Le Heath Manor

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 6 Issue 1 92-118 4-23-2017 A Light in the Darkness – the Taper Burns of Donington le Heath Manor House Alison Fearn PhD Candidate, University of Leicester Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Fearn, Alison. "A Light in the Darkness – the Taper Burns of Donington le Heath Manor House." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 6, 1 (2017): 92-118. https://digital.kenyon.edu/ perejournal/vol6/iss1/23 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fearn A Light in the Darkness – the Taper Burns of Donington le Heath Manor House By Alison Fearn, PhD candidate, University of Leicester Summary In 2016 the author undertook an in-depth survey and analysis of the medieval manor house of Donington le Heath in Leicestershire. During the investigation, a large number of markings and graffiti were recorded across the structure. Further analysis of the markings, their form, and their distribution led to the conclusion that most were ritual in nature and were created to add a significant layer of spiritual protection to vulnerable areas of the structure. Introduction The vast majority of the markings recorded at Donington le Heath are considered to be “ritual protection marks”; symbols that had an apotropaic function, which, in their simplest form were designed to ward off evil influences and misfortune. -

The White House Zion Hill Coleorton LE67 8JP

The White House Zion Hill Coleorton LE67 8JP £675,000 A DELIGHTFUL COUNTRY COTTAGE of charm & character with a STYLISH MODERN INTERIOR, occupying a wonderful mature plot with a SWEEPING GRAVEL DRIVE, spacious versatile interior of over 2,500 sq ft, with 3 reception rooms, fitted kitchen, 5 DOUBLE BEDROOMS 3 bathrooms, double garage, LARGE GARDENS Property Features and quartz work surfaces with matching units within the utility room. Completing the ground floor is the versatile Country Cottage 5 DoubleBedrooms bedroom five, currently doubling as a home office with a Excellent Plot 3 Reception rooms large en-suite bathroom. On the first floor are a further four genuine double bedrooms including the master bedroom Versatile Interior 3 Bathrooms with built in wardrobes and en-suite shower room, the main family bathroom has also been re-fitted with a stylish Over 2,500 sq ft Bespoke Kitchen modern suite. Double garage Super Fast Broadband An impressive sweeping gravel driveway with electric gates off Clay Lane provides more than ample parking and access Full Description to the attached double garage. The mature and established lawned gardens wrap around the property, with a sunken sun terrace, ideally positioned for outdoor entertaining and within the grounds are the ruins of a stone building and a The White House is a delightful country cottage of charm & number of mature fruit trees. character which occupies an excellent private well screened plot on the corner of Zion Hill and Clay Lane. Dating back in Lying in a semi rural position within the sought after hamlet part to the 18th century, the property has been further of Peggs Green in the parish of Coleorton, which is a small extended and adapted, creating a versatile spacious interior village with 3 great pubs, village post office, Church and of over 2500 sq ft including the garage, which also offers village primary school, lying approximately four miles from huge potential to further extend & convert if required. -

A History of Woolcombing, Yarn Spinning & Framework Knitting In

A HISTORY OF WOOLCOMBING, YARN SPINNING & FRAMEWORK KNITTING IN LOCAL VILLAGES BY SAMUEL T STEWART – MAY 2020 1 EXTRACTS FROM THE REPORTS IN PART 3 2 CONTENTS PART 1 – PAGE 4 A SYNOPSIS OF THE WOOL COMBING INDUSTRY BASED MAINLY ON RESEARCH CARRIED OUT BY THE AUTHOR ON THE SHERWINS’ OF COLEORTON PART 2 – PAGE 7 THE FRAMEWORK KNITTING INDUSTRY PART 3 – PAGE 13 REPORTS FROM THE COMMISSIONERS’ ON FRAMEWORK KNITTERS IN LEICESTERSHIRE, CARRIED OUT BY ORDER OF THE HOUSE OF LORDS IN 1845 - Reports from Belton (page 14) - Reports from Whitwick (page 17) - Report from Osgathorpe (page 32) - Reports from Thringstone (page 33) FURTHER RECOMMENDED READING – FRAMEWORK KNITTING BY MARILYN PALMER SHIRE LIBRARY © Samuel T Stewart – May 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise without first seeking the written permission of the author 3 PART 1 A SYNOPSIS OF THE WOOL COMBING INDUSTRY BASED ON RESEARCH CARRIED OUT ON THE SHERWINS’ OF COLEORTON The author has written a book entitled “The Coleorton Sherwins’ 1739-1887” from which certain parts of the following are taken. This is on the author’s website as a free to down load and read pdf doc. In order to understand the Framework Knitting industry which features later, it is necessary to first understand something about the production of the raw material (yarns) used in the knitting process. It should be noted that the word “Hosier” is a general description for a manufacturer involved in the hosiery industry. -

Barrowmore Model Railway Journal·

ISSN 1745-9842 Barrowmore Model Railway Journal· Number33 December 2012 Published on behalf ofBarrowmore Model Railway Group by the Honorary Editor: David Goodwin, "Cromef', Church Road, Saughall, Chester CHI 6EN; tel. 01244 880018. E-mail: [email protected] Contributions are welcome: (a) as e-mails or e-mail attachments; (b) a hard copy of a computer file; (c) a typed manuscript; (d) a hand-written manuscript, preferably with a contact telephone number so that any queries can be sorted out; (e) aCD/DVD; (f) a USB storage flash drive. · Any queries to the Editor, please. The NEXT ISSUE will be dated March 2013, and contributions should get to the Editor as soon as possible, but at least before 1 February 2013. ++111I11l++H+++l1 I 111 1111111II111++++11I111111++++++++1III11II11111111 1111++++1I11111 Copies of this magazine are also available to non-members: a cheque for £9 (payable to 'Barrowmore Model Railway Group') will provide the next four issues, posted direct to your home. Send your details and cheque to the Editor at the above address. I I I I 11III11 11IIII11 I l++I 111 I I I I I I 11 I I I 11III11IIIIl+II11 I 11 I l++++++++++++++++++++I I I I I I I I The cover illustration for this issue is one of a couple of photographs of Barrowmore, of unknown provenance, discovered by Harry Wilson when he was unpacking some belongings transferred from his former house in Tarvin. Readers will recall that Harry rented a couple of units at Barrowmore, using them for storage of the book-stock of his bookselling business. -

2021 May-June

GRAND TRUNK Barnton Slippage at Soot Hill See pp. 12/13 May/June 2021 www.trentandmerseycanalsociety.org.uk Chairman’s Bit As you can read on page 14, our canal has finally been reopened at Soot Hill near Anderton. We can personally report that passage both ways was easy, having just been though (and back) on a return cruise to Worsley. There are signs asking you to proceed at tick-over, a buoyed channel, and two CRT staff to explain why you need to be careful. The landslip is quite spectacular! Let us hope that the earth doesn’t move again, or there could be a renewed closure! On our return trip we were delayed deep within Barnton Tunnel. We were about half-way through when another boat came in towards us. Despite much honking (from both boats) we eventually stopped “bow to bow”. Apparently, they hadn’t seen that we were already in the tunnel! They were surprised to find that they couldn’t pass us inside the tunnel, and horrified to realise that they would have to reverse back out (as we were already ¾ of the way through). Ten minutes later (and in the open air) we politely said “Thank you”, they were full of apologies, and we parted without any hard feelings. Cheshire Lock working parties resumed in April, unfortunately without one stalwart (see page 17). It was great to be at work again, enjoying the open air, the sunshine and chatting to fellow workers (at the regulation Covid-19 distance of course!). Sorry that there is no news yet about our Winter Season of talks for 2021-22. -

A Building Stone Atlas of Leicestershire

Strategic Stone Study A Building Stone Atlas of Leicestershire First published by English Heritage April 2012 Rebranded by Historic England December 2017 Introduction Leicestershire contains a wide range of distinctive building This is particularly true for the less common stone types. In stone lithologies and their areas of use show a close spatial some parts of the county showing considerable geological link to the underlying bedrock geology. variability, especially around Charnwood and in the north- west, a wide range of lithologies may be found in a single Charnwood Forest, located to the north-west of Leicester, building. Even the cobbles strewn across the land by the includes the county’s most dramatic scenery, with its rugged Pleistocene rivers and glaciers have occasionally been used tors, steep-sided valleys and scattered woodlands. The as wall facings and for paving, and frequently for infill and landscape is formed principally of ancient volcanic rocks, repair work. which include some of the oldest rocks found in England. To the west of Charnwood Forest, rocks of the Pennine Coal The county has few freestones, and has always relied on the Measures crop out around Ashby-de-la-Zouch, representing importation of such stone from adjacent counties (notably for the eastern edge of the Derbyshire-Leicestershire Coalfield. To use in the construction of its more prestigious buildings). Major the north-west of Charnwood lie the isolated outcrops of freestone quarries are found in neighbouring Derbyshire Breedon-on-the-Hill and Castle Donington, which are formed, (working Millstone Grit), Rutland and Lincolnshire (both respectively, of Carboniferous Limestone and Triassic working Lincolnshire Limestone), and in Northamptonshire (Bromsgrove) Sandstone.