'Other' Borglum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRINCE of MONACO VISITS CENTER Albert II Attends Patrons Ball

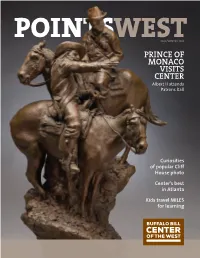

POINTSWEST fall/winter 2013 PRINCE OF MONACO VISITS CENTER Albert II attends Patrons Ball Curiosities of popular Cliff House photo Center’s best in Atlanta Kids travel MILES for learning About the cover: Herb Mignery (b. 1937). On Common Ground, 2013. Bronze. Buffalo Bill and Prince Albert I of Monaco hunting together in 1913. Created by the artist for to the point HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco. BY BRUCE ELDREDGE | Executive Director ©2013 Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Points West is published for members and friends of the Center of the West. Written permission is required to copy, reprint, or distribute Points West materials in any medium or format. All photographs in Points West are Center of the West photos unless otherwise noted. Direct all questions about image rights and reproduction to [email protected]. Bibliographies, works cited, and footnotes, etc. are purposely omitted to conserve space. However, such information is available by contacting the editor. Address correspondence to Editor, Points West, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, 720 Sheridan Avenue, Cody, Wyoming 82414, or [email protected]. ■ Managing Editor | Marguerite House ■ Assistant Editor | Nancy McClure ■ Designer | Desirée Pettet Continuity gives us roots; change gives us branches, ■ Contributing Staff Photographers | Mindy letting us stretch and grow and reach new heights. Besaw, Ashley Hlebinsky, Emily Wood, Nancy McClure, Bonnie Smith – pauline r. kezer, consultant ■ Historic Photographs/Rights and Reproductions | Sean Campbell like this quote because it describes so well our endeavor to change the look ■ Credits and Permissions | Ann Marie and feel of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West “brand.” On the one hand, Donoghue we’ve consciously kept a focus on William F. -

Leonard Gordon Park Master Plan Report

Leonard Gordon Park Master Plan Report Submitted To: Jersey City Division of Architecture February 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Honorable Steven M. Fulop, Mayor Department of Administration: Brian D. Platt, Business Administrator Brian Weller, ASLA, LLA, Division of Architecture, Director Keith Donath, Mayor’s Office Robert Byrne, RMC, CMR, City Clerk Municipal Council for the City of Jersey City: Department of Housing, Economic Development & Commerce: Rolando R. Lavarro, Jr. Council President Tanya Marione AICP, PP, Division of Planning, Director Joyce Watterman, Councilwoman-At-Large Dan Wrieden, Historic Preservation Officer Daniel Rivera, Councilman-At-Large Denise Ridley, Councilwoman, Ward A Laura Skolar, Jersey City Parks Coalition, President Mira Prinz-Arey, Councilwoman, Ward B Arthur Williams, Department of Recreation, Director Richard Boggiano, Councilman, Ward C Michael Yun, Councilman, Ward D All of the Jersey City residents that energetically participated James Solomon, Councilman, Ward E in the public meetings and questionnaires providing positive input that was utilized in the Leonard Gordon Park Master plan Jermaine D. Robinson, Councilman, Ward F development and other City Park development projects. ii City of Jersey City | Leonard Gordon Park Master Plan Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ...........................................................................................1 Section 1: Master Plan Process and Context ............................................ 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................6 -

Gordon Bond All Were Created by Sculptors Who Also Have Celebrated Works in Newark, New Jersey

Sitting in Military Park, at the heart of Newark’s downtown revival, Gutzon Borglum’s 1926 “Wars of America” monumental bronze is far more subtle than its massive size suggests, and possessing of a fascinating and complicated history few who pass by it each day are aware of. hat does Mount Rushmore, the Washington quarter, W and New York's famed Trinity Church Astor Doors all have in common? Gordon Bond All were created by sculptors who also have celebrated works in Newark, New Jersey. When people hear "Newark," they almost gardenstatelegacy.com/Monumental_Newark.html certainly don't think of a city full of monuments, memorials, and statuary by world renowned sculptors. Yet it is home to some forty-five public monuments reflecting a surprising artistic and cultural heritage—and an underappreciated resource for improving the City's image. With recent investment in Newark's revitalization, public spaces and the art within them take on an important role in creating a desirable environment. These memorials link the present City with a past when Newark was among the great American metropolises, a thriving center of commerce and culture standing its ground against the lure of Manhattan. They are a Newark’s “Wars of America” | Gordon Bond | www.GardenStateLegacy.com Issue 42 December 2018 chance for resident Newarkers to reconnect with their city's heritage anew and foster a sense of pride. After moving to Newark five years ago, I decided to undertake the creation of a new guidebook that will update and expand on that idea. Titled "Monumental Newark," the proposed work will go deeper into the fascinating back-stories of whom or what the monuments depict and how they came to be. -

Mathews Is Elected Senior President Song Leader DR

ATTEND HEAR CONVOCATION DR. SMITH THE BALL STATE NEWS BALL STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE, MUNCIE, INDIANA, OCTOBER 6, 1944 Price Five Cents Vol. 24, No. 2 Z - 186 Mathews Is Elected Senior President Song Leader DR. H. AUGUSTINE SMITH Forty- Seven Fort Wayne Girl To Be Here Cadet Nurses Selected As New Enroll Here In Programs Leader of Class at Elli- Dr. H. Augustine Smith To New Group Housed ott — Take Classes With Carmen Moody, Loren Betz Speak, Display Pictures, Student Nurses. Paul Manship Lead Sings. and Dick Valandingham Forty-seven girls are enrolled this Head Other Classes — year in the Ball Memorial Hospital To Give Talk On October 9, 10, and 11 Dr. H. School of Nursing, beginning their Other Officers, SEC Mem- Augustine Smith, well-known song studies on September 18, it has been leader, authority on hymnology, and Famous Sculptor To Be bers Also Chosen. author, will be the guest speaker and announced by Miss Margaret I. Boal, director of nurses. Brought to Campus for leader of several programs for fac- Betty Mathews, active member of ulty and students of Ball State cam- All but four of this group are ca- Convo Program. det nurses, and six are enrolled in senior class, was elected president pus. the new four-year curriculum. The of the class of 1945. She is a gradu- Dr. Smith, who occupies the Chair arrival of this new group of students Members of the Muncie Art Asso- ate of Central High School of Fort of Sacred Music and Kindred Arts at To Be on Campus brings the total enrollment in the ciation and the Convocations Com- Wayne and is president of Alpha Boston University, will bring with mittee are bringing to our campus an Sigma Alpha and W. -

Gutzon Borglum Collection

Gutzon Borglum collection Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 1 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Gutzon Borglum collection AAA.borggutz Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Gutzon Borglum collection Identifier: AAA.borggutz Date: 1926-1981 Creator: Borglum, Gutzon, 1867-1941 Extent: 1 Reel (ca. 1,000 items (on 1 microfilm reel)) Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Microfilmed as part of the Archives of American Art's Texas project. Location of Originals Originals in the San Antonio Museum of Art. Available Formats 35mm microfilm reel 3056 available for use through interlibrary loan. Restrictions The Archives of American art does not -

A Kid's Guide To

A Kid’s Guide To Atlanta A Kid’s Guide To s guid kid’ e t PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERSa PROPERTYo OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS A Kid’s Guide to Atlanta is your own personal tour guide when you and your family venture out to explore all this great city has to offer! It’s jam packed with colorful pictures and fun facts about Atlanta’s history, landmarks, PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS neighborhoods, and more! Atlanta All the interesting stuff that makes Atlanta such an amazing place to discover is waiting inside, along with a way-cool map and stickers that will help you along your journey. PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF Lights Publishers Twin TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS Twin Lights Publishers, Inc. PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS Photography by Paul Scharff • Written by Sara Day PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS ’s guid PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERSkid PROPERTYe t OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS a o PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS Atlanta PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS Photography by Paul Scharff PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERSWritten by Sara Day PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS Copyright © 2013 by Twin Lights Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS permission of the copyright owners. -

Save Outdoor Sculpture!

Save Outdoor Sculpture! . A Survey of Sculpture in Vtrginia Compiled by Sarah Shields Driggs with John L. Orrock J ' Save Outdoor Sculpture! A Survey of Sculpture in Virginia Compiled by Sarah Shields Driggs with John L. Orrock SAVE OUTDOOR SCULPTURE Table of Contents Virginia Save Outdoor Sculpture! by Sarah Shields Driggs . I Confederate Monuments by Gaines M Foster . 3 An Embarrassment of Riches: Virginia's Sculpture by Richard Guy Wilson . 5 Why Adopt A Monument? by Richard K Kneipper . 7 List of Sculpture in Vrrginia . 9 List ofVolunteers . 35 Copyright Vuginia Department of Historic Resources Richmond, Vrrginia 1996 Save Outdoor Sculpture!, was designed and SOS! is a project of the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, and the National prepared for publication by Grace Ng Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Property. SOS! is supported by major contributions from Office of Graphic Communications the Pew Charitable Trusts, the Getty Grant Program and the Henry Luce Foundation. Additional assis Virginia Department of General Services tance has been provided by the National Endowment for the Arts, Ogilvy Adams & Rinehart, Inc., TimeWarner Inc., the Contributing Membership of the Smithsonian National Associates Program and Cover illustration: ''Ligne Indeterminee'~ Norfolk. Members of its Board, as well as many other concerned individuals. (Photo by David Ha=rd) items like lawn ornaments or commercial signs, formed around the state, but more are needed. and museum collections, since curators would be By the fall of 1995, survey reports were Virginia SOS! expected to survey their own holdings. pouring in, and the results were engrossing. Not The definition was thoroughly analyzed at only were our tastes and priorities as a Common by Sarah Shields Driggs the workshops, but gradually the DHR staff wealth being examined, but each individual sur reached the conclusion that it was best to allow veyor's forms were telling us what they had dis~ volunteers to survey whatever caught their eye. -

3/Rz^ Sjgfiature of Certifying Official/Title Bfate/ Amy Cradic

NPS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service /7Q National Register of Historic Places NAT. KtbiblhK OF HISTOR!P~ Registration Form NATIONAL PARK This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________________ historic name Theodore Roosevelt Monument______________________________________ other names/site number Roosevelt Common; Theodore Roosevelt Memorial_______________ 2. Location ______________________________________ street & number Roosevelt Common, Riveredge Road___________________ | | not for publication city or town Borough of Tenafly vicinity State New Jersey code NJ county Bergen code 003 zip code 07670 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I certify that this >c nomination | _ | request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x meets | | does not m§et~the National Register criteria. -

Who Was Solon Borglum? - Taken from “Solon H

Who was Solon Borglum? - taken from “Solon H. Borglum – A Man Who Stands Alone” written by his son-in-law, A. Mervyn Davies. James M. Borglum, a woodcarver in Denmark and a Mormon immigrated to Utah in 1864 with his new bride, Ida Mikkelson, followed by Ida’s family, as they were Mormons also. The following year James also married Ida’s youngest sister Christina. She had 2 sons......John Gutzon, March 25, 1867 (the family always called him Johnnie) and a year and a half later Solon Hannibal was born December 22, 1868. After 3 years of emotional pressures between the two sisters, by mutual consent Christina left the family and rejoined to her parents later remarried. She never stayed in touch with the Borglum family so her where about is unknown . While the boy were still very young James Borglum family changed religions and moved to Fremont NE. Eventually Ida had 4 boys and 3 girls, they raised all 9 children as one family. It became apparent that Nebraska’s treeless plains needed physicians more than they needed a woodcarver. So James studied medicine until he received his M.D. degree at the Missouri Medical (homeopathic) College in St. Louis, February 19, 1874. Now Dr. James Miller Borglum hung out his first shingle in Fremont, NE. Solon was a happy boy and had a passion for the outdoor and for horses and was the only member of his family to really appreciate fully the advantages of a stable full of horses, which the country doctor maintained. Solon learned to ride before he could walk. -

Conner Rosenkranzl

CONNER • ROSENKRANZ LLC 19th & 20th Century American Sculpture Saul Baizerman (1889-1957) Born in Vitebsk, Russia, Saul at the American Artists School in New York and the Baizerman was motivated to become a sculptor University of Southern California. from an early age. Discouraged by his teachers, While Baizerman’s reputation was founded on however, the young and idealistic Baizerman his human-scale works in hammered copper, the turned instead to politics, becoming an active small-scale The City and the People series was to member of the Bolshevik movement. After become his most ambitious and long-lived project. spending a year and a half in an Odessa prison for In fact, it would be one that he would continue having helped rob a bank in order to finance the to work on until his death in 1957. Begun in the cause, Baizerman managed to escape and emigrate early 1920s, this series of approximately 56 small to the United States in 1910. The following year works—generally four to eight inches in height— he renewed his interest in art, taking classes at was originally carved in plaster and then cast in the National Academy of Design, the Beaux-Arts bronze. The final stage required the artist to rework Institute of Design (under Solon Borglum) and the surface with hammers and awls, thus making at the Educational Alliance, where he became each figure unique. The Unemployed, Man with acquainted with Moses Soyer and Chaim Gross. Shovel and Digger are among the earliest works in Having gained technical proficiency, Baizerman the series, having been modeled in 1920 and cast taught sculpture, drawing and anatomy classes at in 1925. -

Transatlantica, 2 | 2017 the Frontier in Paris: Artists from the American West in the French Capital,

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 2 | 2017 (Hi)stories of American Women: Writings and Re- writings / Call and Answer: Dialoguing the American West in France The Frontier in Paris: Artists from the American West in the French Capital, 1890–1900 James R. Swensen Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/10747 DOI: 10.4000/transatlantica.10747 ISSN: 1765-2766 Publisher Association française d'Etudes Américaines (AFEA) Electronic reference James R. Swensen, “The Frontier in Paris: Artists from the American West in the French Capital, 1890–1900 ”, Transatlantica [Online], 2 | 2017, Online since 13 May 2019, connection on 20 May 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/10747 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ transatlantica.10747 This text was automatically generated on 20 May 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. The Frontier in Paris: Artists from the American West in the French Capital, ... 1 The Frontier in Paris: Artists from the American West in the French Capital, 1890–1900 James R. Swensen Introduction Transatlantica, 2 | 2017 The Frontier in Paris: Artists from the American West in the French Capital, ... 2 Figure 1 J.T. Harwood, Paris Still Life (I), c. 1890. Oil on Canvas, 16 x10 inches, Private Collection. Figure 2 J.T. Harwood, Paris Still Life (II), c. 1890. Oil on Canvas, 16 x10 inches, Private Collection. Transatlantica, 2 | 2017 The Frontier in Paris: Artists from the American West in the French Capital, .. -

Designs in Glass

DESIGNS IN GLASS BY TWENTY-SEVEN CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS • STEUBEN . I TWENTY-SE VE N CONTE:\I POHAH Y ARTI ST S THE C OLLE C TIO N O F DE S IG r s I N G LA SS BY TW EN T Y - SEVEN C O N T EM POR A R Y A RTI S T S • S T EUBEN G L ASS I Nc . NE W Y O R K C IT Y C OPYl\ I G H T BY S T EU B EN GLA SS I NC. JA NUA l\Y 1940 c 0 N T E N T s Foreword . SA \l A. L E w 1so 1-1 N Preface tHANK J E WE TT '> l ATll ER, Jn. Nature of the Collecl ion . J o 11 N \I . GATES Numbt·r T l IOMAS BENTON C ll HISTIAN BEH.AHD . 2 MUlHll EAD BONE :J J EAN COCTEAU 'I- J OllN STEUA HT CURRY •• SA LVADOR DA LI (> G IORG IO DE C HllU CO 7 AND 11E DEHAIN s HAOUL D Uf<'Y !I EH!C G ILL 10 DUNCAN G HA NT 11 .! Oll N G HEGOl\Y 12 .! EAL II GO 1 :1 PETEH ll UHD I I MOISE KISLING I ii LEON KROLL . I(> MAHI E LA URENCIN 17 f<'EH NA 'D LEGEH I S ARIST IDE MA LLLO L H> PAUL M.ANS llL P 20 ll ENIH MATISSE 2 1 !SA M U 'OGUClll . 22 G EOHG IA O'KEEf<'FE 2:J .! OSE •!AH IA SEHT 21 PAVEL T C ll E LI T C ll EW .