Creative Non-Fiction in Tertiary Journalism Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEE GUTKIND the Age of the Expert

In FACT LEE GUTKIND The Age of the Expert RECENTLY, I GOT TO poke fun at my boss in front of a crowd. I took some of his writing and pointed out how incredibly boring his prose was, how he went on and on, pontificating LEE GUTKIND is the founder and about a variety of subjects, offering ideas and theories in a way that totally went above the editor of Creative Nonfiction. head of any reader who wasn’t already attuned to his way of thinking. Basically, you might say the problem was this: My boss, Dan Sarewitz—co-author of “Living with the Genie: Essays on Technology and the Quest for Human Mastery” and co-director of the Consortium for Science Policy & Outcomes (CSPO) at Arizona State University, where I am Distinguished Writer in Residence—is a science policy wonk, not a creative writer. So I offered some suggestions about how Dan might tell stories that would illustrate his ideas and, at the same time, engage readers—keep them from falling asleep. Dan took my presentation in the spirit in which it was given: to make a point about how academics should loosen up and recognize there’s another world out there. Then he struck back. He pulled out a copy of my book “Almost Human: Making Robots Think” and focused on a few of my chapters to show what a lightweight I was—how I allowed many important issues to slip by, undeveloped, because I did not think clearly and deeply enough about them. I was so obsessed with narrative and style that I breezed over substance, losing or at least minimizing my ability to make an impact on my readers and perhaps change their perspectives—or so he said. -

Your Creative Future Starts Here

ENROLLMENT Prospective students should review all enrollment documents and videos before their scheduled evaluation. Lincoln Park holds several enrollment seminars a year, usually January through March. YOUR The seminar consists of a tour, admissions video and a meeting with the arts department directors. The admissions video, an overview video from each director and evaluation requirement are all CREATIVE also on our website. EVALUATION FUTURE GUIDELINES STARTS Students interested in applying for the Literary Arts Department should prepare a portfolio of their best written work from one or more genres. HERE. Prospective students will then meet with Literary Arts staff for an evaluation interview. For the complete evaluation guidelines, visit our website, www.lppacs.org. SCHOOL OVERVIEW Through the creative opportunities it offers to its students Lincoln Park is committed to providing the highest-quality education possible. It does so by using an unbeatable blend of cuting-edge technology and old-fashioned academic rigor. Founded in 2006, Lincoln Park is a tuition-free public charter school. It offers world-class training for PA students in music, theatre, dance, literary arts, media arts, health science and the arts, and pre-law and the arts, along with a flexible and challenging academic program. All of these opportunities are provided in a working performing arts center, equipped wioth numerous amenities. Lincoln Park is dedicated to providing student centered service in a professional and compassionate manner. The school utilizes a highly-trained and committed staff, which 1 Lincoln Park, Midland PA 15059 includes a number of professsional artists. 724-643-9004 www.lppacs.org [email protected] Notice of Nondiscriminatory Policy Students at Lincoln Park benefit from individualized As to students, Lincoln Park admits students of any race, color, national and ethnic educational strategies, tailored to each students’ origin to all the rights, privileges, programs, and activities generally accorded or made available to the students at the school. -

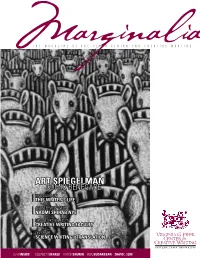

Marginalia Spring 06.Indd

THE MAGAZINE OF THE PIPER CENTER FOR CREATIVE WRITING ART SPIEGELMAN COMIX RENEGADE LISA DAVIS ON THIS WRITER’S LIFE AN INTERVIEW WITH NAOMI SHIHAB NYE NEW BOOKS BY ASU’S CREATIVE WRITING FACULTY ON GENRE: SCIENCE WRITING | TRANSLATION ALSOINSIDE ELIZABETHSEARLE AARONSHURIN INDUSUDARESAN DAVIDL.ULIN IN THIS ISSUE VOL 2, ISS 2 SPRING 2005 FEATURES EDITOR COMIX WITHOUT SPANDEX ......................................................................... 4 Charles Jensen W. Todd Kaneko explains why Art Spiegelman’s work should be required reading and looks back at how his work has infl uenced a growing interest in “comix.” COPYEDITOR Elizabyth Hiscox HOMECOMING ROYALTY .............................................................................. 7 Tina Hammerton recounts the triumphant returns of ASU Alums Jorn Ake, Kevin Haworth, CONTRIBUTORS Ruth Ellen Kocher, and Richard Yañez for a special Homecoming event. Lisa Davis Patricia Sanders Matthew Gavin Frank Elizabeth Searle THE SCIENCE OF WRITING ......................................................................... 10 Michael Green Aaron Shurin Matthew Gavin Frank explores a burgeoning genre combining the aesthetic of art with the Tina Hammerton Indu Sudaresan exploration of science. Elizabyth Hiscox Greg Thielen Douglas S. Jones David L. Ulin W. Todd Kaneko TRUE TALES OF AN ASU GRAD .................................................................. 13 Molly Meneely Michael Green talks with ASU graduate and autobiographical essayist Laurie Notaro. Naomi Shihab Nye BOOKS IN BLOOM ..................................................................................... -

International Association for Literary Journalism Studies

LITERARY JOURNALISM STUDIES LITERARY SPQ+A: David Abrahamson interviews Michael Norman Return address: Literary Journalism Studies School of Journalism Ryerson University Literary Journalism Studies 350 Victoria Street Vol. 7, No. 2, Fall 2015 Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5B 2K3 In This Issue n Michael Jacobs on Tom Wolfe’s Acid Test n John C. Hartsock on Svetlana Alexievich n Magdalena Horodecka on Kapuściński + Herodotus n Kate McQueen on Sling’s German Crime Reportage n Julien Gorbach on Ben Hecht’s Proto–New Journalism VOL. 7, NO. 2, FALL 2015 7, NO. 2, FALL VOL. n Josh Roiland on the Case for ‘Literary Journalism’ n Nicholas Lemann on the Journalism in Literary Journalism Published at the Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University 1845 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208, United States The Journal of the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies Jack Robinson, who in late 1965 snapped the cover picture of Tom Wolfe at the New York Herald Tribune, shot countless pictures of politicians, film stars, rock stars, celebrities, and, yes, writers, for the New York Times, Vogue, and Life magazines, from the 1950s until the early 1970s, at which point he fled Andy Warhol’s Factory scene, and its excesses, for Memphis, Tennessee. There, he led a much quieter, sober existence as a stained-glass window maker. Courtesy the Jack Robinson Archive, LLC; www.robinsonarchive.com. Literary Journalism Studies The Journal of the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies Vol. 7, No. 2, Fall 2015 ––––––––––––––––– Information -

To Think, to Write, to Publish

To Think, To Write, To Publish Science and Innovation Policy through the Looking Glass of Creative nonfiction By Lee Gutkind, David Guston, and Gwen Ottinger To Think, in which two different kinds of people have to learn to think together under difficult circumstances and do things that, while not utterly unprecedented, are still rare and challenging. Sonja Schmid knows she has only three minutes to make her point—and she has to share that time with her new partner. Ross Carper is standing behind her. He’s in his early 30s, balding, wearing a striped jersey, and reading over her shoulder as she follows her notes. She describes a cigarette break she shared with an aging Russian nuclear reactor operator she had been interviewing, which led to a special moment when their conversation went beyond technical talking points to a personal topic—his relationship with his reactors. Schmid, with a cascade of wavy black hair, black-rimmed glasses, and chic red scarf, is an assistant professor in the Department of Science and Technology in Society at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Carper is a writer with the Envi- ronmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Schmid has a PhD in Science and Technology Studies and Carper an MFA in fiction writing. They met each other only a few hours ago and yet they are already collaborating on a writing project that will consume them for 18 months. Now they have but three minutes to convince four very critical editors that readers—educated people who had rarely, if ever, given thought to nuclear reactors or their operators—would want to read about Schmid’s w Drawing of physician, research. -

For Immediate Release the Heinz Endowments and the Pittsburgh

For Immediate Release The Heinz Endowments and The Pittsburgh Foundation Announce Sixteen Grants to Artists and Organizations Awards Totaling $216,206 Will Support Projects Throughout Region Pittsburgh, PA, May 25, 2012 – The Heinz Endowments and The Pittsburgh Foundation have awarded grants to sixteen artists and organizations during the first funding cycle of Investing in Professional Artists, a program jointly sponsored by the foundations. Applications to the new program were received from 137 individuals and organizations from twenty-three cities and towns throughout the region. A peer panel comprising regional and national experts from a variety of artistic disciplines reviewed applications and made awards to thirteen artists and three organizations based on the quality of the artist’s work and the potential of the proposed project to advance the artist’s career. Grantees include established and emerging artists working in visual arts, multimedia, dance, music, theater and literature. A complete list of grants appears below. Investing in Professional Artists is a multi-year program whose goals are to support creative development of professional artists in the region; create career advancement and recognition opportunities for artists; encourage creative partnerships between artists and local organizations, and increase the visibility of working artists in the region’s cultural life. National Panelists included Lee Gutkind (Founding Editor of Creative Nonfiction Journal), Bill Horrigan (Curator-at-Large at the Wexner Center), Valerie Cassel Oliver (Senior Curator at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston), Steven Stucky (Pulitzer Prize-winning composer), Laurie Uprichard (former Executive Director of Danspace Project and the Dublin Dance Festival), Meiyin Wang (Associate Producer of Under The Radar Festival and Symposium in New York). -

True Stories, Well Told

Creative "" Nonfiction Has Been Keeping It Real for YOUR STUDENT. 20 Years LEADING. When students are immersed in challenging coursework — from rigorous post-AP classes to college-level research — it’s no wonder they go on to the nation’s finest colleges and beyond. Come visit and see why WT is unlike any other school in the region. wenty years ago, a battle Visit to learn more: [email protected] • 412-578-7518 raged within literary circles. True Stories, It was a war of words over the genre known as creative nonfiction. TNonfiction writers were increasingly City Campus, Shadyside Allison Park presenting information in vivid, unconven- Co-ed, Pre-K through Grade 12 Co-ed, Pre-K through Grade 5 tional ways in order to attract a broader www.winchesterthurston.org www.wtnorth.org Well Told readership to a wide range of subjects, but not everyone was buying it. Not, that is, BY MARY S. GILBERT until East End resident Lee Gutkind took matters into his own hands. MELODY FARRIN PHOTOS BY The genre—in which writers employ a technique variously referred to as experien- MCCABE tial reportage, immersion, or true story- telling—already had a distinguished histo- BROS., ry. Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, Ernest Inc. Hemingway’s Death in the Afternoon, and $##!# George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London are well-known examples. By Funeral Homes &" inserting themselves into situations with their subjects and using a first-person nar- rative, those authors and others like them &#$!& made their subjects come alive, communi- cating ideas and emotions along with infor- %%% "!"" mation.