HLB 24 1 BOOK.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merrymount Press Records: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8j96csq No online items Merrymount Press Records: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Diann Benti and Kate Peck. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © January 2020 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Merrymount Press Records: mssMerrymount 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Merrymount Press Records Dates (inclusive): 1893-1950 Collection Number: mssMerrymount Creator: Merrymount Press Extent: 364 boxes and 236 volumes (439.92 linear feet) Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection consists of the business records of the Merrymount Press of Boston, Massachusetts, and papers of its owner Daniel Berkeley Updike (1860-1941). The Press, which operated for 45 years, was known for its excellence in typography and design, especially in the field of decorative printing and bookmaking. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation [Identification of item]. Merrymount Press Records, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. -

TM Cleland Papers

T. M. Cleland Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Prepared by Grover Batts with the assistance of Thelma Queen Revised by Joseph K. Brooks Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2012 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms011089 Collection Summary Title: T. M. Cleland Papers Span Dates: 1880-1964 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1920-1963) ID No.: MSS16147 Creator: Cleland, T. M. (Thomas Maitland), 1880-1964 Extent: 6,750 items ; 27 containers ; 11 linear feet Language: Collection material in English, Swedish, and French Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Book designer and illustrator. Correspondence, drawings, and title pages and designs for books and advertisements. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Altschul, Frank, 1887-1981--Correspondence. Anthoensen, Fred, 1882-1969--Correspondence. Armitage, Merle, 1893-1975--Correspondence. Artzybasheff, Boris, 1899-1965--Correspondence. Beilenson, Peter, 1905-1962--Correspondence. Bennett, Paul A., 1897-1966--Correspondence. Biddle, George, 1885-1973--Correspondence. Bradley, Will, 1868-1962--Correspondence. Cleland family--Correspondence. Cleland family. Cleland, Elinor Woodruff, b. 1871--Correspondence. Cleland, T. M. (Thomas Maitland), 1880-1964. Colish, Abraham, 1882-1963--Correspondence. Cotten, Joseph, 1905-1994--Correspondence. Covey, Arthur Sinclair, 1877-1960--Correspondence. Dothard, Robert L.--Correspondence. -

Stanley Marcus Did

Printed & bound A Newsletter for Bibliophiles February 2019 Printed & Bound focuses on the book as a collectible item and as an example of the printer’s art. It provides information about the history of printing and book production, guidelines for developing a book collection, and news about book-related publications and events. Articles in Printed & Bound may be reprinted free of charge SOMESUCH MINIATURE BOOKS provided that full attribution is given (name and date of Not many collectors of miniature books start their own publication, title and author of publishing companies to produce these tiny tomes, but that’s article, and copyright exactly what Stanley Marcus did. Already a noted collector information). Please request permission via email of rare and fine press books, as well as CEO of his family’s ([email protected]) before renowned Neiman-Marcus stores, Marcus then became a reprinting articles. Unless collector of miniature books. otherwise noted, all content is As his collection grew, Marcus’s first wife, Billie, written by Paula Jarvis, Editor decided that she would like to present him with a miniature and Publisher. version of his memoirs, Minding the Store, for his seventieth Printed & Bound birthday. However, while researching the world of Volume 6 Number 1 publishing, she realized that she should involve her husband February 2019 Issue in the process. Thus, Stanley Marcus embarked on his own publishing enterprise, dedicated to miniature books, and in © 2019 by Paula Jarvis c/o Nolan & Cunnings, Inc. 1975 brought out Minding the Store under his new Somesuch 28800 Mound Road Press imprint. (He had originally hoped to name it Nonesuch Warren, MI 48092 Press after the road he lived on, but that name was already in use by an English firm.) This first production was a bit Printed & Bound is published in disappointing as Marcus discovered that the greatly reduced February, June, and October. -

A Finding Aid to the William Mills Ivins Papers, 1878-1964, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the William Mills Ivins Papers, 1878-1964, in the Archives of American Art Cathy Stover 1988 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Professional and Personal Papers, circa 1908-1961................................ 6 Series 2: Writings, circa 1910-1960....................................................................... 18 Series 3: Publications, 1896-1958......................................................................... 22 Series 4: Miscellaneous, 1915, undated............................................................... -

The Name of the Merrymount Press Is Derived

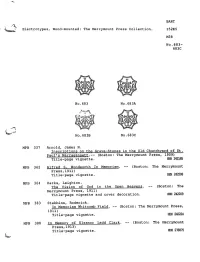

BART -^ Electrotypes, Wood-mounted: The Merrymount Press Collection. I52E5 M38 No.683- 683C No.683A No.683B No.683C MPB 337 Arnold, James N. Inscriptions on the Grave-Stones in the Old Churchyard of St. Paul's Narraaansett.— (Boston: The Merrymount Press, 1909) Title-page vignette. HEH 242185 MPB 362 Alfred S. Woodworth In Memoriam. — (Boston: The Merrymount Press,1911) Title-page vignette. HEH 242208 MPB 364 Parks, Leighton. The Vision of God in the Open Heavens. — (Boston: The Merrymount Press, 1911) Title-page vignette and cover decoration. HEH 242209 MPB 383 Stebbins, Roderick. In Memoriam Whitcomb Field. — (Boston: The Merrymount Press, 1911) Title-page vignette. HEH 242224 MPB 388 In Memory of Eleanor Ladd Clark. — (Boston: The Merrymount Press,1913) Title-page vignette. HEH 278875 aw> BART -A I52E5 M38 No.683- 683C MPB 403 Parker, Cortland. In Memoriam Arthur Rverson. — (Boston: The Merrymount Press, 1914) Title-page vignette. HEH 242233 MPB 458 A Brief History of St. Mary's Church, South Portsmouth & Holy Cross Chapel, Middletown, R.I. — (Boston: The Merrymount Press,1916) Title-page vignette. HEH 279756 MPB 470 Groton School. Responsive Readings. — Groton, Mass. (Boston: The Merrymount Press) Title-page vignette. HEH 278976 MPB 482 Mary Anna Inaell. — (Boston: The Merrymount Press, 1917) Cover-title vignette. HEH 242300 MPB 724 Peabody, Endicott. S In Memoriam William Amorv Gardner. — Groton: Groton School, 1930 (Boston: The Merrymount Press) Title-page vignette. HEH 242457 MPB 788 In Memoriam Gladys Emily Streibert. — New York, 1935 (Boston: The Merrymount Press) Title-page vignette. HEH 242498 MPB 834 Schneider, Herbert Wallace. Meditations in Season on the Elements of Christian Philosophy.- New York: Oxford University Press, 1938 (Boston: The Merrymount Press) Title-page vignette. -

The Contributions of Linn Boyd Benton and Morris Fuller Benton to the Technology of Typesetting and Typeface Design

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 5-1-1986 The Contributions of Linn Boyd Benton and Morris Fuller Benton to the technology of typesetting and typeface design Patricia Cost Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Cost, Patricia, "The Contributions of Linn Boyd Benton and Morris Fuller Benton to the technology of typesetting and typeface design" (1986). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sc~l of Printing Rochester Institute of Techno~ Rochester I New York CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL MASTER'S niESIS This is to certify that the Master's Thesis of Patricia Knittel Cost name of student with a major in Printing Technology has been approved by the Thesis Comnittee as satisfactory for the thesis requirement for the Master of Science degree at the convocation of June 24, 1986 date Thesis Comnittee: Herbert Johnson Thesis Advisor Archibald Provan Thesis Advisor Joseph L. Noga Graduate Progran Coordinator Miles Southworth Director THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF LINN BOYD BENTON AND MORRIS FULLER BENTON TO THE TECHNOLOGY OF TYPESETTING AND TYPEFACE DESIGN by Patricia Knittel Cost A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the School of Printing in the College of Graphic Arts and Photography of the Rochester Institute of Technology May 1986 Thesis Advisors: Herbert H. -

Call 392 Ronald Peters Collection of Private Press Printers and The

Ms Ronald Peters Collection of Private Press Printers and The Call Typophiles • 392 Collection ofcorrespondence, drawings, drafts, proofs, production materials, and printed epehemera by and about private press printers, including The Typophiles, 1913-1977. Gift ofRonald Peters, 2000. Extent: 64 Boxes (8 metres) • • Ms. Call. Peters Collection 2 392 • Arrangement Note These papers are arranged largely as they were received from Ronald Peters, and this finding aid is adapted from one Peters provided, retaining his comments. • • Ms. Call. Peters Collection 3 392 .:' • Boxes & Items 1-8, Thomas Maitland Cleland ovs 63 For a description ofthis collection see The Wide Open Mind; a Catalogue ofa Thomas Maitland Collection. Toronto: Privately printed, 1992 Boxes 1-2 Manuscripts, 1913-1954 Box 1 1913, Giambattista Bodoni folder 1 Lewis Buddy to Cleland, 1913, 1 TLS. Buddy had edited Wisdom of Horace Walpole. It was privately printed in 1905 on hand-made Italian paper (75) copies and on imperial Japan (5 copies), and was the first to be printed in the Bodoni type especially case for Harvard University Press. The volume originally appeared as volume 5, Detached Thoughts in the Works ofHorace Walpole (1798). folders 2-5 "Giambattista Bodoni ofParma". Lecture given to Society of Printers, Boston, 22 April 1913 folder 2 Typescript with holograph revisions in folder with printed title on cover, 30 leaves folder 3 Holograph text, 25 leaves • folder 4 Holograph and typescript, 28 leaves. Removed for folder with printed label pasted on cover folder 5 A Keepsake in Honour ofGiambattista Bodoni ... Society ofPrinters ... April Twenty-second, Nineteen hundred & thirteen" folders 6-8 " Life ofGiambattista Bodoni" by Giuseppi De Lama.