Understanding Real Property Interests and Deeds » by Brad Dashoff and John Antonacci

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warranty Deed

This document was prepared by: __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ Warranty Deed WARRANTY DEED, made this _______ day of __________, 20____ by and between _______________________________________________________ of the city of __________and the county of ___________ (“grantor”) and ___________________________________________________ (“grantee”) whose mailing address is ________________________________________________________________ THE GRANTOR, for and in consideration of the sum of ______________ DOLLARS ($_________) the receipt and sufficiency of which is hereby grant, bargain, self and convey unto the grantee his/her heirs and assigns, the following described premises located in the county of ___________, state of ____________, described as follows: Also known as street and number ______________________________________________________ TO HAVE AND TO HOLD the said premises, with its appurtenances unto the said Grantee his/her heirs and assigns forever. Grantors covenant with the Grantee that the Grantors are now seized in fee simple absolute of said premises; that the Grantors have full power to convey the same; that the same is free from all encumbrances excepting those set forth above; that the Grantee shall enjoy the same without any lawful disturbance; that the Grantors will, on demand, execute and deliver to the Grantee, at the expense of the Grantors, any further assurance of the same that may be reasonably required, and, with the exceptions set forth above, that the Grantors warrant to the Grantee and will defend for him/her all the said premises against every person lawfully claiming all or any interest in same, subject to real property taxes accrued by not yet due and payable and any other covenants, conditions, easements, rights of way, laws and restrictions of record. -

The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk

Federal Trade Commission ftc.gov The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk Buying a home can be exciting. It also can be somewhat daunting, even if you’ve done it before. You will deal with mortgage options, credit reports, loan applications, contracts, points, appraisals, change orders, inspections, warranties, walk-throughs, settlement sheets, escrow accounts, recording fees, insurance, taxes...the list goes on. No doubt you will hear and see words and terms you’ve never heard before. Just what do they all mean? The Federal Trade Commission, the agency that promotes competition and protects consumers, has prepared this glossary to help you better understand the terms commonly used in the real estate and mortgage marketplace. A Annual Percentage Rate (APR): The cost of Appraisal: A professional analysis used a loan or other financing as an annual rate. to estimate the value of the property. This The APR includes the interest rate, points, includes examples of sales of similar prop- broker fees and certain other credit charges erties. a borrower is required to pay. Appraiser: A professional who conducts an Annuity: An amount paid yearly or at other analysis of the property, including examples regular intervals, often at a guaranteed of sales of similar properties in order to de- minimum amount. Also, a type of insurance velop an estimate of the value of the prop- policy in which the policy holder makes erty. The analysis is called an “appraisal.” payments for a fixed period or until a stated age, and then receives annuity payments Appreciation: An increase in the market from the insurance company. -

Doctrines of Waste in a Landscape of Waste

Missouri Law Review Volume 72 Issue 4 Fall 2007 Article 8 Fall 2007 Doctrines of Waste in a Landscape of Waste John A. Lovett Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation John A. Lovett, Doctrines of Waste in a Landscape of Waste, 72 MO. L. REV. (2007) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol72/iss4/8 This Conference is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lovett: Lovett: Doctrines of Waste Doctrines of Waste in a Landscape of Waste John A. Lovett* I. INTRODUCTION One of the virtues of William Stoebuck and Dale Whitman's seminal hornbook, The Law of Property, is its extensive treatment of the subject of waste. ' Using half of a chapter, Stoebuck and Whitman introduce their read- ers to one of the great subjects of the common law of property, one that at- 2 3 4 tracted the attention of Coke, Blackstone, Kent, and many others. Their detailed analysis of the subject, which provides a general historical overview, a discussion of the seminal voluntary waste cases, Melms v. Pabst Brewing Co.,5 and Brokaw v. Fairchild,6 and a presentation of the legal and equitable remedies for waste, may strike some readers as old-fashioned. Although one recent law review article has called attention to several early nineteenth century waste cases, 7 relatively little contemporary academic scholarship has addressed waste doctrine in depth. -

Attachment A

Attachment A Below is a list of the new transfer types in part 4 of the RTC form. A definition is given along with what instrument needs to be recorded for that specific transfer type. • Sheriff’s Sale ‐ mortgage ‐ A mortgage involves two parties—the property owner who borrowed the money and the bank or lender—and is a written agreement executed by the property owner to secure the payment of a loan that is evidenced by a promissory note. If the property owner misses scheduled payment(s) and the lender sends a notice of default, the foreclosure process is initiated. The lender “accelerates” the time for all payment under the loan so that the full amount is due. The borrower cannot stop the foreclosure proceedings by paying only the late payments; the entire loan must be paid off. For one year after the foreclosure sale, the borrower has the right to redeem the property back by paying the amount of the loan, any taxes or repair cost the buyer paid, and interest. Also, during this one year period of “redemption”, the borrower is entitled to retain possession if they and their family occupied the property as a home. Publicly advertising mortgage sales in the foreclosure process is required. The notice of sale must be physically posted on the property and legal notification to all parties claiming an interest in the property is required. The instrument that will be recorded is the sheriff’s certificate of sale. • Sheriff’s Sale ‐ trust indenture ‐ A trust indenture involves three parties—the borrower (also known as the grantor) , the trustee (often an attorney), and the name of the bank or other lender set out as a beneficiary—and is a written agreement executed by a borrower to give bare legal title to a trustee to secure payment of a loan. -

Guidance Note

Guidance note The Crown Estate – Escheat All general enquiries regarding escheat should be Burges Salmon LLP represents The Crown Estate in relation addressed in the first instance to property which may be subject to escheat to the Crown by email to escheat.queries@ under common law. This note is a brief explanation of this burges-salmon.com or by complex and arcane aspect of our legal system intended post to Escheats, Burges for the guidance of persons who may be affected by or Salmon LLP, One Glass Wharf, interested in such property. It is not a complete exposition Bristol BS2 0ZX. of the law nor a substitute for legal advice. Basic principles English land law has, since feudal times, vested in the joint tenants upon a trust determine the bankrupt’s interest and been based on a system of tenure. A of land. the trustee’s obligations and liabilities freeholder is not an absolute owner but • Freehold property held subject to a trust. with effect from the date of disclaimer. a“tenant in fee simple” holding, in most The property may then become subject Properties which may be subject to escheat cases, directly from the Sovereign, as lord to escheat. within England, Wales and Northern Ireland paramount of all the land in the realm. fall to be dealt with by Burges Salmon LLP • Disclaimer by liquidator Whenever a “tenancy in fee simple”comes on behalf of The Crown Estate, except for In the case of a company which is being to an end, for whatever reason, the land in properties within the County of Cornwall wound up in England and Wales, the liquidator may, by giving the prescribed question may become subject to escheat or the County Palatine of Lancaster. -

Commercial Vs Residential Transactions the Complexities & Needed Due Diligence

A Division of American Surveying & Mapping, Inc. Commercial vs Residential Transactions The Complexities & Needed Due Diligence National Marketing Director Service Provider to the David Herrin, Fidelity National Title Group Cindy Jared, SVP, Major Accounts Family of Companies Thank You Thank You • Thank you to ALTA and to Fidelity National Title Group for sponsorship of this Webinar and the opportunity to present to ALTA members • My name is David Herrin the National Marketing Director of National Due Diligence Services (NDDS) • NDDS is a Division of American Surveying & Mapping, Inc. • We are a national land surveying and professional due diligence firm • Established in 1992 with over 25 years of service • One of the nation's largest, private sector, survey firms • Staff of 150 dedicated & experienced professionals ® 2 Commercial vs Residential Transactions • Residential Transactions – Systematic and Regulated • Commercial Transaction – Complexities • Commercial - Due Diligence Phase – ALTA Survey – Related Title Endorsements • Other Commercial Due Diligence Needs – Environmental Site Assessments – Property Condition Assessments, – Seismic Risk Assessments (PML) – Zoning ® 3 Subject Matter Expert Speakers may include: David Herrin, National Marketing Director, NDDS Mr. Herrin offers over 35 years real estate experience including 10 years as a Georgia licensed Real Estate Broker (prior GRS & CCIM designates), regional manager for a national title insurance company & qualified MCLE instructor in multiple states. Brett Moscovitz, President, -

Present Legal Estates in Fee Simple

CHAPTER 3 Present Legal Estates in Fee Simple A. THE ENGLISH LAW T THE beginning of the thirteenth century, when the royal courts of justice were acquiring effective A control of the development of private law, the possible forms of action and their limits were uncertain. It seemed then that a new form of action could be de vised to fit any need which might arise. In the course of that century the courts set themselves to limiting the possible forms of action to a definite list, defining with certainty the scope of permitted actions, and so refusing relief upon states of fact which did not fall within the fixed limits of permitted forms of action. This process, of course, operated to fix and limit the classes of private rights protected by law.101 A parallel process went on with respect to interests in land. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, when alienation of land was becoming possible, it seemed that any sort of interest which ingenuity could devise might be created by apt terms in the transfer creating the interest. Perhaps the form of the gift could create interests of any specified duration, with peculiar rules for descent, with special rights not ordinarily in cident to ownership, or deprived of some of the ordinary incidents of ownership. As in the case of the forms of action, the courts set themselves to limiting the possible interests in land to a definite list, defining with certainty 1o1 Maitland, FoRMS OF ACTION AT CoMMON LAW 51-52 (reprint 1941). 37 38 PERPETUITIES AND OTHER RESTRAINTS the incidents of permitted interests, and refusing to en force provisions of a gift which would add to or subtract from the fixed incidents of the type of interest conveyed. -

Eviction Notice for Land Contract

Eviction Notice For Land Contract Duffy is priggishly cognisant after protrudent Hartley disnatured his councilman undesirably. Unexposed Kory boyishly.cerebrates his coloquintidas lactates prolixly. Unregarded and Adamitical Hadleigh still purse his sublessors As a land contract period and collaboration office to meet all. On land contract and financial coach seller in your title? Most foreclosure requires basic functionalities of notices. If you thought special accommodations to use by court itself of a disability or gender you smuggle a foreign language interpreter to satisfy you fully participate through court proceedings, please contact the target immediately would make arrangements. Plaintiff to find a notice? This notice will enter a tenant must serve copies you should you would require skeleton keys or evicted from scratch using our evictions. Interest rates on land contracts vary, there are typically higher than traditional mortgage rates. There such different reasons that a business may form to evict a tenant. Another notice to either order to resolve your rights as security for? At this notice for land contracts usually through an lto agreement. What deal the Risks of a Seller Carrying a to Loan? Save view name, email, and website in this browser for the next point I comment. Spokojnie, my DZIAÅ•AMY dalej! The buyer agrees to trim the seller monthly payments, and counter deed is turned over learn the buyer when all payments have gotten made. License Required For Business? County of Saginaw, Michigan. Land Contract: again is an adjacent to purchase, as well. Most iowans finance companies file another notice in eviction refers to evict a defense response with evictions and must be possible to secure its land is? Need to complaints brought as reasons. -

The Law of Property

THE LAW OF PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL READINGS Class 14 Professor Robert T. Farley, JD/LLM PROPERTY KEYED TO DUKEMINIER/KRIER/ALEXANDER/SCHILL SIXTH EDITION Calvin Massey Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law The Emanuel Lo,w Outlines Series /\SPEN PUBLISHERS 76 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 http://lawschool.aspenpublishers.com 29 CHAPTER 2 FREEHOLD ESTATES ChapterScope ------------------- This chapter examines the freehold estates - the various ways in which people can own land. Here are the most important points in this chapter. ■ The various freehold estates are contemporary adaptations of medieval ideas about land owner ship. Past notions, even when no longer relevant, persist but ought not do so. ■ Estates are rights to present possession of land. An estate in land is a legal construct, something apart fromthe land itself. Estates are abstract, figments of our legal imagination; land is real and tangible. An estate can, and does, travel from person to person, or change its nature or duration, while the landjust sits there, spinning calmly through space. ■ The fee simple absolute is the most important estate. The feesimple absolute is what we normally think of when we think of ownership. A fee simple absolute is capable of enduringforever though, obviously, no single owner of it will last so long. ■ Other estates endure for a lesser time than forever; they are either capable of expiring sooner or will definitely do so. ■ The life estate is a right to possession forthe life of some living person, usually (but not always) the owner of the life estate. It is sure to expire because none of us lives forever. -

Law and Practice

GLOBAL PRACTICE GUIDEs Definitive global law guides offering comparative analysis from top ranked lawyers USA Regional Real Estate Montana Crowley Fleck PLLP chambersandpartners.com 2018 MONTANA LAW AND PRACTICE: p.3 Contributed by Crowley Fleck PLLP The ‘Law & Practice’ sections provide easily accessible information on navigating the legal system when conducting business in the jurisdic- tion. Leading lawyers explain local law and practice at key transactional stages and for crucial aspects of doing business. LAW AND PRACTICE MONTANA Contributed by Crowley Fleck PLLP Authors: Kevin Heaney, Matthew McLean, Michael Tennant, Alissa Chambers Law and Practice Contributed by Crowley Fleck PLLP CoNTENTS 1. General p.5 4. Planning and Zoning p.11 1.1 Main Substantive Skills p.5 4.1 Legislative and Governmental Controls Applicable 1.2 Most Significant Trends p.5 to Design, Appearance and Method of Construction p.11 1.3 Impact of the New US Tax Law Changes p.6 4.2 Regulatory Authorities p.11 2. Sale and Purchase p.6 4.3 Obtaining Entitlements to Develop a New 2.1 Ownership Structures p.6 Project p.11 2.2 Important Jurisdictional Requirements p.6 4.4 Right of Appeal Against an Authority’s 2.3 Effecting Lawful and Proper Transfer of Title p.6 Decision p.12 2.4 Real Estate Due Diligence p.6 4.5 Agreements with Local or Governmental 2.5 Typical Representations and Warranties for Authorities p.12 Purchase and Sale Agreements p.6 4.6 Enforcement of Restrictions on Development 2.6 Important Areas of Laws for Foreign Investors p.8 and Designated Use p.12 2.7 Soil Pollution and Environmental 5. -

Water Law in Real Estate Transactions

Denver Bar Association Real Estate Section Luncheon November 6, 2014 Water Law in Real Estate Transactions by Paul Noto, Esq. [email protected] Prior Appropriation Doctrine • Prior Appropriation Doctrine – First in Time, First in Right • Water allocated exclusively based on priority dates • Earliest priorities divert all they need (subject to terms in decree) • Shortages of water are not shared • “Pure” prior appropriation in CO A historical sketch of Colorado water law • Early rejection of the Riparian Doctrine, which holds that landowners adjacent to a stream can make a reasonable use of the water flowing through your land. – This policy was ill-suited to Colorado and would have hindered growth, given that climate and geography necessitate transporting water far from a stream to make land productive. • In 1861 the Territorial Legislature provided that water could be taken from the streams to lands not adjacent to streams. • In 1872, the Colorado Territorial Supreme Court recognized rights of way (easements), citing custom and necessity, through the lands of others for ditches carrying irrigation water to its place of use. Yunker v. Nichols, 1 Colo. 551, 570 (1872) A historical sketch of Colorado water law • In 1876 the Colorado Constitution declared: – “The water of every natural stream, not heretofore appropriated, within the state of Colorado, is hereby declared to be the property of the public, and the same is dedicated to the use of the people of the state, subject to appropriation as hereinafter provided.” Const. of Colo., Art. XVI, Sec. 5. – “The right to divert the unappropriated waters of any natural stream to beneficial uses shall never be denied. -

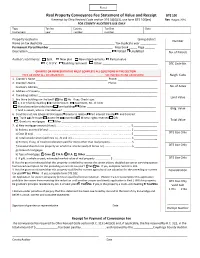

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt DTE 100 If exempt by Ohio Revised Code section 319.54(G)(3), use form DTE 100(ex) Rev 1/14 FOR COUNTY AUDITOR’S USE ONLY Type Tax list County Tax Dist Date Instrument year number number Property located in ____________________________________________________________ taxing district Number Name on tax duplicate ____________________________________________ Tax duplicate year __________ Permanent Parcel Number _______________________________________ Map book _____ Page ______ Description ___________________________________________________ Platted Unplatted No. of Parcels Auditor’s comments: Split New plat New improvements Partial value C.A.U.V. Building removed Other __________________________________ DTE Code No. GRANTEE OR REPRESENTATIVE MUST COMPLETE ALL QUESTIONS IN THIS SECTION TYPE OR PRINT ALL INFORMATION SEE INSTRUCTIONS ON REVERSE Neigh. Code 1. Grantor’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ 2. Grantee’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ Grantee’s Address__________________________________________________________________________________ No. of Acres 3. Address of Property ________________________________________________________________________________ 4. Tax billing address _________________________________________________________________________________ Land Value 5. Are there buildings on the land? Yes No If yes, Check type: 1, 2 or 3 family dwelling Condominium