Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to the Archival and Manuscript Collection of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., New York City

Research Report No. 30 A GUIDE TO THE ARCHIVAL AND MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., NEW YORK CITY A Detailed Inventory Yury Boshyk Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies University of Alberta Edmonton 1988 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies University of Alberta Occasional Research Reports Publication of this work is made possible in part by a grant from the Stephania Bukachevska-Pastushenko Archival Endowment Fund. The Institute publishes research reports periodically. Copies may be ordered from the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 352 Athabasca Hall, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T6G 2E8. The name of the publication series and the substantive material in each issue (unless otherwise noted) are copyrighted by the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. PRINTED IN CANADA Occasional Research Reports A GUDE TO THE ARCHIVAL AND MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., NEW YORK CITY A Detailed Inventory Yury Boshyk Project Supervisor Research Report No. 30 — 1988 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta Dr . Yury Boshyk Project Supervisor for The Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Research Assistants Marta Dyczok Roman Waschuk Andrij Wynnyckyj Technical Assistants Anna Luczka Oksana Smerechuk Lubomyr Szuch In Cooperation with the Staff of The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S. Dr. William Omelchenko Secretary General and Director of the Museum-Archives Halyna Efremov Dima Komilewska Uliana Liubovych Oksana Radysh Introduction The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the United States, New York City, houses the most comprehensive and important archival and manuscript collection on Ukrainians outside Ukraine. -

Paradox Illusions

3DUDGR[,OOXVLRQV $QGUL\=D\DUQ\XN $E,PSHULRSS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\$E,PSHULR )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by University of Winnipeg (15 Sep 2016 23:31 GMT) Andriy Zayarnyuk, Paradox Illusions Andriy ZAYARNYUK PARADOX ILLUSIONS Tarik Cyril Amar’s book engages with an extremely challenging and painful subject. Essentially, it is about present-day Lviv’s roots in the heinous mass murders of World War II and postwar displacements, as well as cruelties and hardships of the postwar Stalinist regime. While Ukrainians (Lviv’s cur- rent majority) often present themselves as victims of those twentieth-century tragedies, the book emphasizes their involvement as both perpetrators of atrocities and collaborators. The subject is tremendously important and the author should be commended for raising it, but the actual execution of his study is seriously flawed. The author sets out to explore how Lviv, an Eastern European borderland city, that was shaped by “four key forces of European and global twentieth- century history: Soviet Communism, Soviet nation-shaping (here, Ukrain- ization), nationalism and Nazism” (P. 1). Whereas, arguably, “Soviet nation- shaping” was not a global force on par with the other three and can hardly be disentangled from the larger “Soviet Communism,” it is central to Amar’s argument. The only aspect of Soviet Communism that the book engages with at any length is its nationality policies. Both local nationalists and the Nazis were molding the city according to their ideals—mostly through atrocious murders, including the murder of the city’s Jewish population. Finishing the ethnic cleansing, however, fell to the Soviets, who removed the Poles and turned the city into a Ukrainian one. -

By Iryna Koshulap Submitted to the Central European University

WOMEN, NATION, AND THE GENERATION GAP: DIASPORIC ACTIVISM OF THE UKRAINIAN NATIONAL WOMEN’S LEAGUE OF AMERICA IN THE POST-COLD WAR ERA By Iryna Koshulap Submitted to the Central European University Department of Gender Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Professor Allaine Cerwonka CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2013 Statement I hereby state that the thesis contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. The thesis contains no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Budapest, June 7, 2013 Iryna Koshulap CEU eTD Collection ©2013. Iryna Koshulap. All rights reserved. ii Abstract The present study examines a co-formative relationship between the diasporic and women‘s activism of the Ukrainian National Women‘s League of America at the time of Ukraine‘s independence. Founded in 1925, this voluntary-based non-profit organization of Ukrainian migrant women and women of Ukrainian descent has carried out philanthropic, educational, and cultural activities along with political protests and lobbying, taking a recognized place among organizations of the Ukrainian diaspora in the United States. Having been a women‘s organization in the Ukrainian diaspora and an ethnic organization in American and international women‘s movements from its inception, the UNWLA often considered its participation in international women‘s forums instrumental in promoting the cause of Ukraine‘s sovereignty. Instead of withdrawing from this arena in the early years of Ukraine‘s independence, however, the UNWLA started to adopt the women‘s rights and equality discourses for generating relations with the state and non-state actors in Ukraine and for conceptualizing a vision for the organization‘s future. -

Occupation and Inter-Ethnic Relations in Lviv 1939-1944

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): Christoph Mick Article Title: Incompatible Experiences: Poles, Ukrainians and Jews in Lviv under Soviet and German Occupation, 1939-44 Year of publication: 2011 Link to publication: http://jch.sagepub.com/ Link to published article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022009410392409 Publisher statement: Mick, C. (2011). Incompatible Experiences: Poles, Ukrainians and Jews in Lviv under Soviet and German Occupation, 1939-44. Journal of Contemporary History, 46(2), pp. 336- 363. Incompatible experiences: Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews in Lviv under Soviet and German occupation, 1939-1944 „What men think is more important in history than the objective facts.‟ (A.J.P. Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848-1918 (Oxford, New York 1991), 17) Perceptions of reality and not reality itself determine the behaviour of people. Such perceptions are at the same time subjective and socially determined. While most historians would agree with these statements, in historical practice such truisms are often disregarded. When the perceptions of historical actors diverge from the reconstructed reality, this is seen as an expression of false consciousness. To avoid such specious conclusions I have chosen an approach based on what in German is termed Erfahrungsgeschichte, that is, the history of experience. -

Ukraine. 1932-1933. Genocide by Famine

On the cover: «Bitter Childhood Memory» from the National Museum «Memorial to Victims of Holodomor» in Kyiv. Sculptors- Mykola Obezyuk and Petro Drozdowskiy. UKRAINE 1932-1933 GENOCIDE BY FAMINE Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance «The Memorial to Victims of the Holodomor» National Museum Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine Ministry of Information Policy of Ukraine The following institutions provided materials for the Exhibit: The H. S. Pshenychny Central State Archives of Film, Photo and Sound State Archive Branch of the Security Services of Ukraine The Ivan Honchar Museum — National Center of Folk Culture National Art Museum of Ukraine Institute of History of Ukraine, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine The M. Ptukha Institute of Demography and Social Studies, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine ISBN Photographs provided by V. Udovytchenko and S. Lypovetsky HOLODOMOR – EXPLANATION AND PREVENTION The word Holodomor means the deliberate mass mur- Eyewitnesses to the crime of the Holodomor and its history der by famine from which there is no salvation. Ukrainians teach us what is worth doing and what is ineffective in pre- use this name when referring to the National Catastrophe of venting genocides and in fighting those who plan and organ- 1932 – 33. ize them We begin with the fact that the Holodomor was one of It is always imperative for us to study the past intensive- the most important events not only in Ukraine’s history, but ly so that we can immediately recognize the symptoms of also in 20th century world history. Without understanding evil. Even though evil has different faces, its nature is always this, it is difficult to grasp the nature of totalitarianism and the same. -

Ukrainianization, Terror and Famine: Coverage in Lviv's Dilo and The

1 Author's Accepted Manuscript of an article published in Nationalities Papers: The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity 40.3 (2012): 431-52. Available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com. Ukrainianization, terror and famine: coverage in Lviv’s Dilo and the nationalist press of the 1930s Myroslav Shkandrij The years 1932-34 were a turning point in Soviet Ukraine. Ukrainian nationalism was declared the “greatest danger,” replacing Russian great-power chauvinism which had held this distinction since the Twelfth Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik) in 1923. Pavel Postyshev arrived from Moscow to implement the new line, which was that Ukrainianization had hitherto been a “Petliurite” operation aimed at developing a national culture and state, instead of being a tool for bolshevization (See Martin 356, 362-68). Sweeping arrests and show trials were conducted in order to intimidate those who were conducting Ukrainianization and to make the republic completely subservient to the party centre in Moscow. By the late thirties, korenizatsiia (the policy of rooting bolshevik rule in local populations) was seen as best done through Russification, and not through cooperation with supporters of a national renaissance that, in Stalin’s view, had interfered with the strengthening of bolshevik power (Iefimenko 13). After gaining control of the party and crushing the Ukrainian peasantry, Stalin began undermining Ukrainianization by linking it to nationalism and the disasters of collectivization. An incorrect, “Petliurite” Ukrainianization, it was pronounced, had stimulated resistance to party policies, caused shortages in grain-requisitioning and led to revolts. The Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party stated on December 14, 1932, that a lack of “bolshevik vigilance” had allowed “the twisting of the party line” (Ibid. -

N in Ukraine 27 Hennadii Yefimenko

VOL 1 • ISSUE 1 • 2009 n i n o m In Memoriam: Raphael Lemkln [1900-1959] Raphael Lemkin on the Ukrainian genocide Memories of Communist and Nazi Crimes Polish Diplomats on the Holodomor Red Cross Documents on the Great Famine HOLODOMOR STUDIES EDITOR Roman Serbyn Universite du Quebec a Montreal, Canada Email: Serbvn.Roman@Videotron. ca HOLODOMOR STUDIES is published semi annually. Subscription rates are: Institutions - $40.00; Individuals - $20.00. USA postage is $6.00; Canadian postage is $12.00; foreign postage is $20.00. Send payment to: Charles Schlacks, Publisher, P.O. Box 1256, Idyllwild, CA 92549-1256, USA. Email: [email protected] Cover Design: Olena Sullivan, Toronto, Can ada. www.olena.ca Manuscripts submitted for possible publication should be sent to the editor. Manuscripts ac cepted for publication should be sent to the pub lisher as email attachments or on CDs suitable for Windows XP and Word 2003. Copyright © 2009 by Charles Schlacks, Pub lisher All rights reserved Printed in the USA Vol. 1, No. 1 Winter-Spring 2009 HOLODOMOR STUDIES TABLE OF CONTENTS PUBLISHER’S PREFACE v Charles Schlacks EDITOR’S FOREWORD vii Roman Serbyn IN MEMORIAN: RAPHAEL LEMKIN [1900-1959] Lemkin on the Ukrainian Genocide 1 Roman Serbyn Soviet Genocide in Ukraine 3 Raphael Lemkin ARTICLES Competing Memories o f Communist and Nazis Crimes in Ukraine 9 Roman Serbyn The Soviet Nationalities Policy Change of 1933, or Why “Ukrainian Nationalism ” Became the Main Threat to Stalin in Ukraine 27 Hennadii Yefimenko Foreign Diplomats on the -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1995, No.11

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE: • Ambassador Yuri Shcherbak meets with community leaders — page 3. • Senate hearings examine U.S. foreign aid — page 8. • Ukrainian American named director of Ukraine s national symphony — page 1 1. THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXIII No. 11 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, MARCH 12, 1995 75 cents Ivan Kedryn-Rudnytsky, dean Ukraine to receive IMF loan will be in Kyyiv next week to lend his of Ukrainian journalists, dies at 98 *£S£5Z" personal support to this government pro gram," said Graeme Justice, the IMF's senior resident representative in Ukraine. signed a memorandum on March 3 avin Rudnytsky, perhaps the last representa- 1||^^ > P £ Mr. Camdessus spoke to President Leonid Kuchma on Wednesday evening and agreed to visit Kyyiv on March 9. (That decades, and a long-time Svoboda editor- ^^^^^^ШХ^ш^^^^^^^Ш^ International Monetary Fund, announced a visit has since been postponed to March 10, said the presidential press office, with Mr. Camdessus traveling to Moscow on March 9 and then to Ukraine.) The IMF director told the Ukrainian president that he would "exert maximum served in the Austrian army (1914-1916), ^^^^^ИВИІ^ ІіїІІІІІ approximately $1.5 billion which will be effort" to ensure Ukraine obtained a sub and later joined the Ukrainian National ^^^^^^^^Ш ШШШШЯ disbursed in several installments throughout stantial loan package within the next few :: ч weeks. Mr. Rudnytsky studied at the University ^^^^^^^ ^pl^ ^•^ ІІ5і§§5 prime minister in the Ukrainian govern The main purpose of his visit is to or" Vienna in 1920-1923, where he worked ^^^^^^Ш Щт ІІІІ1І1І ment durin§ a news conference, In show support for economic reform in, as co-editor of the weekly journal Volia, ІІІ^^^^^^^Ш^Ь ..^^^^Д addition, Ukraine has also request- Ukraine and confirm the IMF's intention adopting the pseudonym Kedryn, among ||||^^^^^^^^ДШ^^^^^И ed the second drawing of the IMF's sys- (Continued on page 3) After graduating, he moved to Lviv and IS it secured last October. -

Conditio Sine Qua Non, EWJUS, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2017

Review Essay: Conditio sine qua non 275 Review Essay Conditio sine qua non Ola Hnatiuk Centre for East European Studies, University of Warsaw Department of History, National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy Translated from Ukrainian by Iaroslava Strikha Mariusz Sawa. Ukraiński emigrant: Działalność i myśl Iwana Kedryna- Rudnyckiego (1896-1995) [Ukrainian Emigrant: The Activities and Thought of Ivan Kedryn-Rudnytsky (1896–1995)]. Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2016. 400 pp. Illustrations. Bibliography. Indexes. PLN 31,00, cloth. iographies do not constitute a well-developed genre of writing in B Ukraine. Popular biographies and biographic scholarly monographs are in short supply, even those dealing with the most prominent and central figures of Ukrainian history. Book-length biographies about Galicians are particularly scant: with few exceptions, these individuals’ “Galician nature”—assigned a status of marginality in the historiographic paradigm that has been carried over from the twentieth century—has caused them to be excluded from the pantheon of important figures about whom biographies are written. The elevated genre of intellectual biography, which spans the disciplines of history, philosophy, and political studies, is represented by very few works (first and foremost among them is Prorok u svoii vitchyzni: Franko ta ioho spil'nota [1856-1886] [A Prophet in His Own Homeland: Franko and His Community (1856-1886)] by Iaroslav Hrytsak). The publishing market in Poland is a completely different story: biographies (and memoirs) are among the most popular published genres. Furthermore, Poland has the most active publishing market outside of Ukraine with regard to books on Ukrainian topics, including the history of Ukraine. Each year, several dozen books on Ukrainian issues are published; naturally, these include biographies. -

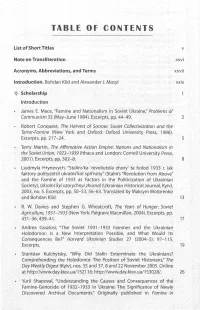

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Short Titles v Note on Transliteration xxvi Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms xxvii Introduction, Bohdan Klid and Alexander J. Motyi xxtx 1) Scholarship 1 Introduction James E. Mace, "Famine and Nationalism in Soviet Ukraine," Problems of Communism 33 (May-June 1984). Excerpts, pp. 44-49, 2 Robert Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986). Excerpts, pp. 217-24. 5 . Terry Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939 (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2001). Excerpts, pp. 302-8. 8 • Liudmyla Hrynevyeh, "Stalins'ka 'revoliutsiia zhory' ta holed 1933 r. iak faktory polityzatsiT ukraTns'koY spil'noty" (Stalin's "Revolution from Above" and the Famine of 1933 as Factors in the Politicization of Ukrainian Society), Ukra'ins'kyi istorychnyi zhurnal (Ukrainian Historical journal, Kyiv), 2003, no, 5. Excerpts, pp. 50-53, 56-63. Translated by Maksym Motorenko and Bohdan Klid. 13 R. W. Davies and Stephen G, Wheatcroft, The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931-1933 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). Excerpts, pp. 431-36,439-41. 1? • Andrea Graziosi, "The Soviet 1931-1933 Famines and the Ukrainian Holodomor: Is a New Interpretation Possible, and What Would Its Consequences Be?" Harvard Ukrainian Studies 27 (2004-5); 97-115. Excerpts. 19 • Stanislav Kulchytsky, "Why Did Stalin Exterminate the Ukrainians? Comprehending the Holodomor. The Position of Soviet Historians," The Day Weekly Digest {Kyiv), nos. 35 and 37, 8 and 22 November 2005. Online at http://www.day.kiev.ua/152116; http://www.diiy.kiev.ua/153028/. -

Women and Holodomor-Genocide : Victims, Survivors, Perpetrators

WOMEN AND HOLODOMOR-GENOCIDE : VICTIMS, SURVIVORS, PERPETRATORS SECOND SYMPOSIUM Commemorating the 85th Anniversary of the Holodomor-Genocide California State University, Fresno Henry Madden Library, 2206 OCTOBER 5, 2018 Cover art: “The Bitter Memory of Childhood” This haunting statue of a young girl clutching a handful of wheat stalks stands in the middle of the alley leading to the Memorial in Commemoration of the Victims of the Holodomor in Kyiv, Ukraine. The statue is dedicated to the most vulnerable victims of the Ukrainian famine-genocide – children. The statue, as part of the memorial complex, was conceptualized and designed by the Ukrainian folk artist Anatoliy Haydamaka and architect Yuriy Kovalyov for the 75th commemorative year. Wheat is the symbol of life, prosperity, spiritual wealth. It is the grain which, for centuries, has been associated with our nation’s livelihood. During the 1932-1933, however, it became a weapon of the genocide orchestrated to destroy the very fabric of that nation. On August 7, 1932, Joseph Stalin authored a law with a sentence ten years of imprisonment or death for the misappropriation of collective farm property. This law led to mass arrests and executions. Even children caught picking handfuls of grain from collective farm fields were convicted. It became known as the law of “Five Ears of Grain.” While serving as a reminder of the devastation characterized by the law, the wheat symbolizes the Ukrainian nation’s determination to live and prosper; the nation’s future. PROGR AM Friday, October 5 BREAKFAST Poster Exhibit “We Were Killed Because We Are Ukrainians” Presented by the Holodomor Victims Memorial, Kyiv, Ukraine 8:00 a.m. -

3) EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS and MEMOIRS Introduction This Section

3) EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS AND MEMOIRS Introduction This section contains descriptions, reports, and memoirs of the famine by eyewitnesses and contemporaries. In Kapoot, Carveth Wells, a world traveler and writer, notes that “the farther we penetrated into the Ukraine” in July 1932, “the less food there was and the more starvation to be seen on every side.” This is followed by one of the first reports of 1933 about the famine, filed by Gareth Jones: it was immediately disputed by the New York Times reporter Walter Duranty. Two other journalists, Malcolm Muggeridge and William Chamberlin, both saw the famine as a struggle between the Soviet state and the peasantry and blamed the authorities for it. The French journalist Suzanne Bertillon interviewed Martha Stebalo, an American citizen of Ukrainian origin who had visited famine-stricken Ukraine in July–August 1933. She concludes that the Kremlin organized the famine to destroy Ukrainian hopes of self-rule. Harry Lang, a journalist with the Yiddish-language Jewish Daily Forward (New York), provides horrific details of the famine, notes the resistance of Ukraine’s peasants to collective farming, likens a village to “cemeteries of houses,” and recognizes that the famine was man- made. He visits a model Jewish collective farm, noting that aid from Jews living abroad helped save its members from starvation. Whiting Williams, who traveled in Ukraine in 1933, describes how peasants hoped to save their children by abandoning them in Kharkiv. He was told that these “wild children” would be “unloaded out in the open country—too far out for it to be possible to walk back to town.” Eugene Lyons describes how Western journalists downplayed or failed to report on the famine.