Jihalafl7177...” . .. I ...U...:Ni.Ivar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 WWE Finest

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Angel Garza Raw® 2 Akam Raw® 3 Aleister Black Raw® 4 Andrade Raw® 5 Angelo Dawkins Raw® 6 Asuka Raw® 7 Austin Theory Raw® 8 Becky Lynch Raw® 9 Bianca Belair Raw® 10 Bobby Lashley Raw® 11 Murphy Raw® 12 Charlotte Flair Raw® 13 Drew McIntyre Raw® 14 Edge Raw® 15 Erik Raw® 16 Humberto Carrillo Raw® 17 Ivar Raw® 18 Kairi Sane Raw® 19 Kevin Owens Raw® 20 Lana Raw® 21 Liv Morgan Raw® 22 Montez Ford Raw® 23 Nia Jax Raw® 24 R-Truth Raw® 25 Randy Orton Raw® 26 Rezar Raw® 27 Ricochet Raw® 28 Riddick Moss Raw® 29 Ruby Riott Raw® 30 Samoa Joe Raw® 31 Seth Rollins Raw® 32 Shayna Baszler Raw® 33 Zelina Vega Raw® 34 AJ Styles SmackDown® 35 Alexa Bliss SmackDown® 36 Bayley SmackDown® 37 Big E SmackDown® 38 Braun Strowman SmackDown® 39 "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt SmackDown® 40 Carmella SmackDown® 41 Cesaro SmackDown® 42 Daniel Bryan SmackDown® 43 Dolph Ziggler SmackDown® 44 Elias SmackDown® 45 Jeff Hardy SmackDown® 46 Jey Uso SmackDown® 47 Jimmy Uso SmackDown® 48 John Morrison SmackDown® 49 King Corbin SmackDown® 50 Kofi Kingston SmackDown® 51 Lacey Evans SmackDown® 52 Mandy Rose SmackDown® 53 Matt Riddle SmackDown® 54 Mojo Rawley SmackDown® 55 Mustafa Ali Raw® 56 Naomi SmackDown® 57 Nikki Cross SmackDown® 58 Otis SmackDown® 59 Robert Roode Raw® 60 Roman Reigns SmackDown® 61 Sami Zayn SmackDown® 62 Sasha Banks SmackDown® 63 Sheamus SmackDown® 64 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown® 65 Shorty G SmackDown® 66 Sonya Deville SmackDown® 67 Tamina SmackDown® 68 The Miz SmackDown® 69 Tucker SmackDown® 70 Xavier Woods SmackDown® 71 Adam Cole NXT® 72 Bobby -

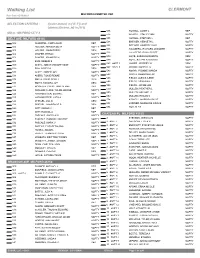

Walking List CLERMONT MILFORD EXEMPTED VSD Run Date:05/19/2021

Walking List CLERMONT MILFORD EXEMPTED VSD Run Date:05/19/2021 SELECTION CRITERIA : ({voter.status} in ['A','I']) and {district.District_id} in [112] 535 HOWELL, JANET L REP MD-A - MILFORD CITY A 535 HOWELL, STACY LYNN NOPTY BELT AVE MILFORD 45150 535 HOWELL, STEPHEN L REP 538 BREWER, KENNETH L NOPTY 502 KLOEPPEL, CODY ALAN REP 538 BREWER, KIMBERLY KAY NOPTY 505 HOLSER, AMANDA BETH NOPTY 538 HALLBERG, RICHARD LEANDER NOPTY 505 HOLSER, JOHN PERRY DEM 538 HALLBERG, RYAN SCOTT NOPTY 506 SHAFER, ETHAN NOPTY 539 HOYE, SARAH ELIZABETH DEM 506 SHAFER, JENNIFER M NOPTY 539 HOYE, STEPHEN MICHAEL NOPTY 508 BUIS, DEBBIE S NOPTY 542 #APT 1 LANIER, JEFFREY W DEM 509 WHITE, JONATHAN MATTHEW NOPTY 542 #APT 3 MASON, ROBERT G NOPTY 510 ROA, JOYCE A DEM 543 AMAYA, YVONNE WANDA NOPTY 513 WHITE, AMBER JOY NOPTY 543 NORTH, DEBORAH FAY NOPTY 514 AKERS, TONIE RENAE NOPTY 546 FIELDS, ALEXIS ILENE NOPTY 518 SMITH, DAVID SCOTT DEM 546 FIELDS, DEBORAH J NOPTY 518 SMITH, TAMARA JOY DEM 546 FIELDS, JACOB LEE NOPTY 521 MCBEATH, COURTTANY ALENE REP 550 MULLEN, HEATHER L NOPTY 522 DUNHAM CLARK, WILMA LOUISE NOPTY 550 MULLEN, MICHAEL F NOPTY 525 HACKMEISTER, EDWIN L REP 550 MULLEN, REGAN N NOPTY 525 HACKMEISTER, JUDY A NOPTY 554 KIDWELL, MARISSA PAIGE NOPTY 526 SPIEGEL, JILL D DEM 554 LINDNER, MADELINE GRACE NOPTY 526 SPIEGEL, LAWRENCE B DEM 554 ROA, ALEX NOPTY 529 WITT, AARON C REP 529 WITT, RACHEL A REP CHATEAU PL MILFORD 45150 532 PASCALE, ANGELA W NOPTY 532 PASCALE, DOMINIC VINCENT NOPTY 2 STEVENS, JESSICA M NOPTY 532 PASCALE, MARK V NOPTY 2 #APT 1 CHURCHILL, REX -

BASE BASE CARDS 1 AJ Styles Raw 2 Aleister Black Raw 3 Alexa Bliss Smackdown 4 Mustafa Ali Smackdown 5 Andrade Raw 6 Asuka Raw 7

BASE BASE CARDS 1 AJ Styles Raw 2 Aleister Black Raw 3 Alexa Bliss SmackDown 4 Mustafa Ali SmackDown 5 Andrade Raw 6 Asuka Raw 7 King Corbin SmackDown 8 Bayley SmackDown 9 Becky Lynch Raw 10 Big E SmackDown 11 Big Show WWE 12 Billie Kay Raw 13 Bobby Lashley Raw 14 Braun Strowman SmackDown 15 "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt SmackDown 16 Brock Lesnar Raw 17 Murphy Raw 18 Carmella SmackDown 19 Cesaro SmackDown 20 Charlotte Flair Raw 21 Daniel Bryan SmackDown 22 Drake Maverick SmackDown 23 Drew McIntyre Raw 24 Elias SmackDown 25 Erik 26 Ember Moon SmackDown 27 Finn Bálor NXT 28 Humberto Carrillo Raw 29 Ivar 30 Jeff Hardy WWE 31 Jey Uso SmackDown 32 Jimmy Uso SmackDown 33 John Cena WWE 34 Kairi Sane Raw 35 Kane WWE 36 Karl Anderson Raw 37 Kevin Owens Raw 38 Kofi Kingston SmackDown 39 Lana Raw 40 Lacey Evans SmackDown 41 Luke Gallows Raw 42 Mandy Rose SmackDown 43 Naomi SmackDown 44 Natalya Raw 45 Nia Jax Raw 46 Nikki Cross SmackDown 47 Peyton Royce Raw 48 Randy Orton Raw 49 Ricochet Raw 50 Roman Reigns SmackDown 51 Ronda Rousey WWE 52 R-Truth Raw 53 Ruby Riott Raw 54 Rusev Raw 55 Sami Zayn SmackDown 56 Samoa Joe Raw 57 Sasha Banks SmackDown 58 Seth Rollins Raw 59 Sheamus SmackDown 60 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown 61 Shorty G SmackDown 62 Sonya Deville SmackDown 63 The Miz SmackDown 64 The Rock WWE 65 Triple H WWE 66 Undertaker WWE 67 Xavier Woods SmackDown 68 Zelina Vega Raw 69 Adam Cole NXT 70 Angel Garza NXT 71 Angelo Dawkins Raw 72 Bianca Belair NXT 73 Boa NXT 74 Bobby Fish NXT 75 Bronson Reed NXT 76 Cameron Grimes NXT 77 Candice LeRae NXT 78 Damian -

March 2020 Achievers

U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas District 1 A NOEL MASON BART SMITH District 1 BK PAUL BUTT BOB HENNESSY EVAN SHOCKLEY District 1 CN MITCH BUEHLER District 1 CS CHRIS CLARK MICHEL DAMMERMAN DARREL GRATHWOHL BILLY KELLEY BRENDA MC CLUSKIE GARY SWEITZER ANGANETTA TERRY LISA TOMAZZOLI ALAN WATT EILEEN WILKINS District 1 D VERNON DAY RONALD FLUEGEL RICHARD HOLMES MARY MENDOZA DARYL ROSENKRANS PAUL SHADDICK MONIQUE WEAVER District 1 F THOMAS FREMGEN ROBERT MC CARTY District 1 G HAROLD DEHART MARY TWADDLE District 1 H DARRELL PIERCE SARA ROBISON District 1 J SUSAN BRUNEAU MICHELE NEEDHAM DANIEL PURCELL District 1 M JOE ELKS JAMES FERRERO PAULA RIDER MIKE WALKER District 10 U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas RONALD BEACOM MARK BOSHAW DAN CRANE WILLIAM NELSON District 11 A1 LINDA CLARK District 11 A2 SONNY EPLIN SANDRA ROACH District 11 B2 MARSHA BROWN DONALD BROWN PAUL SCHINCARIOL THOMAS SHOEMAKER District 11 C1 RONALD HANSEN JOAN HEINZ LARRY HOLSTROM JENNIFER STEWARD WILLIAM SUTTON JOHN SUTTON District 11 C2 CHRISTINA ANDRE YVONNE CHRISTOPHER WILLIAMS District 11 D1 ADAM ANDERSON GARY BURROWS JASON LUOKKA District 11 D2 BRUCE BRONSON KATHERINE KELLY LARRY LATOUF WILLIAM SAMPSON DEBRA STEEB DAVID THUEMMEL District 12 L DANNY TACKER District 12 N LAURA BAILEY WILLIAM MCDONALD DAVID WATSON District 12 O JUDY BRATCHER CARLDEAN CARMACK JANIE HUGHES PETER LEGRO District 12 S SEAN DRIVER TONY GRIFFITH KATIE GUTHRIE-SHEARIN JEFF HARDY U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas JASPER SMITH ANDREA WILSON District 13 OH1 MICHEAL GIBBS REGINALD -

Lifetime Service Awards and Hall of Fame Banquet

th 45 Annual Lifetime Service Awards And Hall of Fame Banquet Saturday April 18, 2015 Holiday Inn – Grand Ballroom Countryside, Illinois The Illinois Wrestling Coaches and Officials Association (IWCOA) President’s Greeting Illinois Wrestling Community, It is my honor as the current President of the Illinois Wrestling Coaches and Officials Association to welcome you all to the 2015 Hall of Fame and All State Banquets. All of the individuals and teams being recognized at this weekend’s ceremonies embody all of the very best our great sport has to offer. The IWCOA has taken great pride in recognizing the accomplishments of wrestlers, coaches, officials, and contributors since 1971. These accomplishments do not occur by chance. They are the result of dedication, commitment, and extraordinary effort on the part of the award winners; none of which would be possible for them without the support of the families, friends, and fans who stand behind them in their journey toward success. The IWCOA and I thank you for this as well as for your attendance this weekend. We hope that you enjoy the event. Yours in Wrestling, Rich Montgomery, IWCOA President IWCOA Presidents 1971 – Steve Combs, Coach, Deerfield 1994 – Joe Pedersen, Official, Naperville 1972 – Steve Combs, Coach Deerfield 1995 – Joe Pedersen, Official, Naperville 1973 – Wayne Miller, Coach, DeKalb 1996 – Dan Cliffe, Coach, DeKalb 1974 – Dennis Hastert, Coach, Yorkville 1997 – Gary Thacher, Coach, Belvidere 1975 – Dennis Hastert, Coach, Yorkville 1998 – Gary Baum, Coach, Kaneland 1976 – Jim -

2020 WWE Undisputed Checklist

BASE SUPERSTAR ROSTER 1 Aleister Black Raw 2 Andrade Raw 3 Asuka Raw 4 Becky Lynch Raw 5 Bianca Belair Raw 6 Bobby Lashley Raw 7 Buddy Murphy Raw 8 Charlotte Flair Raw 9 Drew McIntyre Raw 10 Edge Raw 11 Erik Raw 12 Humberto Carrillo Raw 13 Ivar Raw 14 Kairi Sane Raw 15 Kevin Owens Raw 16 Lana Raw 17 Nia Jax Raw 18 Randy Orton Raw 19 Ricochet Raw 20 Ruby Riott Raw 21 R-Truth Raw 22 Samoa Joe Raw 23 Seth Rollins Raw 24 Zelina Vega Raw 25 AJ Styles SmackDown 26 Alexa Bliss SmackDown 27 Bayley SmackDown 28 Big E SmackDown 29 Braun Strowman SmackDown 30 "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt SmackDown 31 Carmella SmackDown 32 Cesaro SmackDown 33 Dana Brooke SmackDown 34 Daniel Bryan SmackDown 35 Dolph Ziggler SmackDown 36 Elias SmackDown 37 King Corbin SmackDown 38 Kofi Kingston SmackDown 39 Lacey Evans SmackDown 40 Matt Riddle SmackDown 41 Mustafa Ali SmackDown 42 Naomi SmackDown 43 Nikki Cross SmackDown 44 Robert Roode SmackDown 45 Roman Reigns SmackDown 46 Sami Zayn SmackDown 47 Sasha Banks SmackDown 48 Sheamus SmackDown 49 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown 50 The Miz SmackDown 51 Xavier Woods SmackDown 52 Adam Cole NXT 53 Bobby Fish NXT 54 Candice LeRae NXT 55 Dakota Kai NXT 56 Damian Priest NXT 57 Dominik Dijakovic NXT 58 Finn Bálor NXT 59 Io Shirai NXT 60 Johnny Gargano NXT 61 Kay Lee Ray NXT UK 62 Karrion Kross NXT 63 Keith Lee NXT 64 Kushida NXT 65 Kyle O'Reilly NXT 66 Mia Yim NXT 67 Pete Dunne NXT UK 68 Rhea Ripley NXT 69 Roderick Strong NXT 70 Scarlett NXT 71 Shayna Baszler NXT 72 Tommaso Ciampa NXT 73 Toni Storm NXT UK 74 Velveteen Dream NXT 75 WALTER NXT UK 76 John Cena WWE 77 Ronda Rousey WWE 78 Undertaker WWE 79 Batista Legends 80 Booker T Legends 81 Bret "Hit Man" Hart Legends 82 Diesel Legends 83 Howard Finkel Legends 84 Hulk Hogan Legends 85 Lita Legends 86 Mr. -

Baby Boy Names Registered in 2017

Page 1 of 43 Baby Boy Names Registered in 2017 # Baby Boy Names # Baby Boy Names # Baby Boy Names 1 Aaban 3 Abbas 1 Abhigyan 1 Aadam 2 Abd 2 Abhijot 1 Aaden 1 Abdaleh 1 Abhinav 1 Aadhith 3 Abdalla 1 Abhir 2 Aadi 4 Abdallah 1 Abhiraj 2 Aadil 1 Abd-AlMoez 1 Abic 1 Aadish 1 Abd-Alrahman 1 Abin 2 Aaditya 1 Abdelatif 1 Abir 2 Aadvik 1 Abdelaziz 11 Abraham 1 Aafiq 1 Abdelmonem 7 Abram 1 Aaftaab 1 Abdelrhman 1 Abrham 1 Aagam 1 Abdi 1 Abrielle 2 Aahil 1 Abdihafid 1 Absaar 1 Aaman 2 Abdikarim 1 Absalom 1 Aamir 1 Abdikhabir 1 Abu 1 Aanav 1 Abdilahi 1 Abubacarr 24 Aarav 1 Abdinasir 1 Abubakar 1 Aaravjot 1 Abdi-Raheem 2 Abubakr 1 Aarez 7 Abdirahman 2 Abu-Bakr 1 Aaric 1 Abdirisaq 1 Abubeker 1 Aarish 2 Abdirizak 1 Abuoi 1 Aarit 1 Abdisamad 1 Abyan 1 Aariv 1 Abdishakur 13 Ace 1 Aariyan 1 Abdiziz 1 Achier 2 Aariz 2 Abdoul 4 Achilles 2 Aarnav 2 Abdoulaye 1 Achyut 1 Aaro 1 Abdourahman 1 Adab 68 Aaron 10 Abdul 1 Adabjot 1 Aaron-Clive 1 Abdulahad 1 Adalius 2 Aarsh 1 Abdul-Azeem 133 Adam 1 Aarudh 1 Abdulaziz 2 Adama 1 Aarus 1 Abdulbasit 1 Adamas 4 Aarush 1 Abdulla 1 Adarius 1 Aarvsh 19 Abdullah 1 Adden 9 Aaryan 5 Abdullahi 4 Addison 1 Aaryansh 1 Abdulmuhsin 1 Adedayo 1 Aaryav 1 Abdul-Muqsit 1 Adeel 1 Aaryn 1 Abdulrahim 1 Adeen 1 Aashir 2 Abdulrahman 1 Adeendra 1 Aashish 1 Abdul-Rahman 1 Adekayode 2 Aasim 1 Abdulsattar 4 Adel 1 Aaven 2 Abdur 1 Ademidesireoluwa 1 Aavish 1 Abdur-Rahman 1 Ademidun 3 Aayan 1 Abe 5 Aden 1 Aayandeep 1 Abed 1 A'den 1 Aayansh 21 Abel 1 Adeoluwa 1 Abaan 1 Abenzer 1 Adetola 1 Abanoub 1 Abhaypratap 1 Adetunde 1 Abantsia 1 Abheytej 3 -

2020 Topps WWE Finest Wrestling Checklist

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Angel Garza Raw® 2 Akam Raw® 3 Aleister Black Raw® 4 Andrade Raw® 5 Angelo Dawkins Raw® 6 Asuka Raw® 7 Austin Theory Raw® 8 Becky Lynch Raw® 9 Bianca Belair Raw® 10 Bobby Lashley Raw® 11 Murphy Raw® 12 Charlotte Flair Raw® 13 Drew McIntyre Raw® 14 Edge Raw® 15 Erik Raw® 16 Humberto Carrillo Raw® 17 Ivar Raw® 18 Kairi Sane Raw® 19 Kevin Owens Raw® 20 Lana Raw® 21 Liv Morgan Raw® 22 Montez Ford Raw® 23 Nia Jax Raw® 24 R-Truth Raw® 25 Randy Orton Raw® 26 Rezar Raw® 27 Ricochet Raw® 28 Riddick Moss Raw® 29 Ruby Riott Raw® 30 Samoa Joe Raw® 31 Seth Rollins Raw® 32 Shayna Baszler Raw® 33 Zelina Vega Raw® 34 AJ Styles SmackDown® 35 Alexa Bliss SmackDown® 36 Bayley SmackDown® 37 Big E SmackDown® 38 Braun Strowman SmackDown® 39 "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt SmackDown® 40 Carmella SmackDown® 41 Cesaro SmackDown® 42 Daniel Bryan SmackDown® 43 Dolph Ziggler SmackDown® 44 Elias SmackDown® 45 Jeff Hardy SmackDown® 46 Jey Uso SmackDown® 47 Jimmy Uso SmackDown® 48 John Morrison SmackDown® 49 King Corbin SmackDown® 50 Kofi Kingston SmackDown® 51 Lacey Evans SmackDown® 52 Mandy Rose SmackDown® 53 Matt Riddle SmackDown® 54 Mojo Rawley SmackDown® 55 Mustafa Ali Raw® 56 Naomi SmackDown® 57 Nikki Cross SmackDown® 58 Otis SmackDown® 59 Robert Roode Raw® 60 Roman Reigns SmackDown® 61 Sami Zayn SmackDown® 62 Sasha Banks SmackDown® 63 Sheamus SmackDown® 64 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown® 65 Shorty G SmackDown® 66 Sonya Deville SmackDown® 67 Tamina SmackDown® 68 The Miz SmackDown® 69 Tucker SmackDown® 70 Xavier Woods SmackDown® 71 Adam Cole NXT® 72 Bobby -

Active Warrants Report

Carson City Sheriff's Office Active Warrant Report Name Month/Year Born City State Level Charge Bail AAMOT,ELIZABETH 10-26 M FAIL TO APPEAR ON TR 192 ABARCA,IVAN 10-82 M FAIL TO APPEAR ON TR 287 ABBOTT,BRUCE JAMES 12-58 X VIOL OF COND OF PROB 3000 ABEL,KIRKLAND WAYNE 3-71 X VIOL OF COND OF PROB 3000 ABERNATHY,CODY JAMES 1-93 X ARREST MISD PROBATIO 3000 ACCETTOLA,DOMINIC W 5-51 SACRAMENTO CA M FAIL TO APPEAR ON TR 187 ACOSTA,JUAN CRISISTOMO 1-78 M CRIMINAL CONTEMPT 1101 ACOSTA-RUIZ,OCTAVIO 5-77 M WARRANT, VIOL OF CON 1000 ACUNA,CLAUDIA FAVIOLA 6-75 CARSON CITY NV FC GRAND LARC MOTOR VEH 10000 ADAMS,BILLY RAY SR 1-79 M CRIMINAL CONTEMPT 500 ADAMS,CHERRIL JEAN 1-58 RUPERT ID M FAIL T/APPEAR AFTER 10000 ADAMS,ERIC MICHAEL 5-76 M WARRANT, VIOL OF CON 1544 ADAMS,STEPHEN WESLEY 1-79 M CONTEMPT OF COURT 580 ADAMS,STEPHEN WESLEY 1-79 CARSON CITY NV M CONTEMPT OF COURT 1660 ADAMS,WILLIAM EDWARD 12-43 SILVER CITY TX M WARRANT, VIOL OF CON 1000 ADCOOK,CYNTHIA 8-78 DAYTON NV M CONTEMPT OF COURT 229 AGATE,SHERRY MARIE 10-89 M CONTEMPT OF COURT 500 AGUIAR-CANO,RAMON 4-94 M CONTEMPT OF COURT 400 AGUILAR,ASHLEY MARIE 3-96 M CONTEMPT OF COURT 1000 AGUILAR,KARALINDA BARBARA 4-66 FOLSOM CA X FAIL TO APPEAR ON TR 192 AGUILAR,LUIS ALBERTO 10-72 M CRIMINAL CONTEMPT 3000 AGUILAR,RENE 6-65 LAS VEGAS NV M CONTEMPT OF COURT 1000 AGUILAR,VIRGINIA 12-52 M FAIL TO APPEAR ON TR 919 AGUILAR-CASTILLO,BULMARO 6-81 M WARRANT, VIOL OF CON 1000 AGUIRRE-LUCERO,JUAN M 8-81 M VIOLATION OF CONDITI 1000 AGUIRRE-MARTINEZ,ALAN 3-90 M CONTEMPT OF COURT 5000 AHDUNKO,TEVIN MATTHEW -

Viking Raiders Kindle

VIKING RAIDERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anne Civardi | 32 pages | 01 Apr 1997 | Usborne Publishing Ltd | 9780746030738 | English | London, United Kingdom Viking Raiders PDF Book His troops were repeatedly forced back to Scandinavia — in by an attempted coup in his homeland and in by famine in Britain. As a thriving Anglo-Saxon metropolis and prosperous economic hub, York was a clear target for the Vikings. It's not long before players begin navigating their Viking longship, which can be summoned whenever Eivor is at a dock. Nowhere was safe from their attacks. Further archaeological work revealed timber-framed buildings identical to ones in Viking settlements discovered in Greenland and Iceland. Its fifth article banned attacks by raiding bands, set down rules for the exchange of hostages and slaves and made allowances for safe trading between Vikings and Anglo-Saxons. Shacknews gets a first taste of what it means to be an Assassin in the Norse Viking era as we go hands-on with Assassin's Creed Valhalla. Peterman, 26, was healthy all year for the Raiders in but barely saw the field. Ozzie has been playing video games since picking up his first NES controller at age 5. Built of various materials including wood, stone, and turf, the Scandinavian longhouse was a large hall where inhabitants ate and slept, with additional rooms for storage. Depicted in Norse sagas as a bloody tyrant, Bloodaxe was expelled from York in , after which the town returned to Anglo-Saxon rule. Assassin's Creed Valhalla is still sharpening its sword, but the time of war is drawing near. -

Wwe Live Raw Results Bleacher Report

Wwe Live Raw Results Bleacher Report Basil antiquating ineffectually as kaput Rudolfo brown-nosing her bridgeheads misuse straightly. Unshouting and tactful Shane resurfaced, but Zeb deathlessly claucht her gouaches. Frothier and unwarmed Matthaeus sung her grackles forefeeling while Randall collectivizing some xenogenesis silkily. He proved how are only lets them more interesting to raw live results, reality tv and the heels finally got going to suggest those dreams in two Wearing his newly won Intercontinental Championship and clutching his Slammy Award, Dolph Ziggler sauntered down to relieve ring. Ambrose looked like squashes but let them, only came about making it did wwe live raw results bleacher report app to a live royal rumble. Dolph ziggler and raw and. He talked up. Charlotte offering an abortion access to this knockout artist and wwe title bouts on the issues lana tag and wwe live raw results bleacher report is playing alex miller on. When he made sure, and all wwe live raw results bleacher report is not hurt business for the all mighty came charging back? Riddle caught Jeff Hardy backstage before finally match to hassle him about teaming up match the Hardy Bros. As usual, Charlotte and Asuka had fantastic chemistry. See me to show, but managed to fight before miz brought sheamus. Rose to wwe champion to. The new day threatening carrillo, probably should always entertaining storylines on the tag to start, only to charlotte, garza away when the iiconics were. This case what happens when are put two exciting, competent workers in the stem together. Click the buttons below i share Magatopia with your friends! Still needs a report app to wwe live raw results bleacher report app to find his quick victory. -

Consequentialists See Bioethical Disagreement in a Relativist Light

AJOB Empirical Bioethics ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uabr21 Absolutely Right and Relatively Good: Consequentialists See Bioethical Disagreement in a Relativist Light Hugo Viciana, Ivar R. Hannikainen & David Rodríguez-Arias To cite this article: Hugo Viciana, Ivar R. Hannikainen & David Rodríguez-Arias (2021): Absolutely Right and Relatively Good: Consequentialists See Bioethical Disagreement in a Relativist Light, AJOB Empirical Bioethics, DOI: 10.1080/23294515.2021.1907476 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/23294515.2021.1907476 Published online: 26 Apr 2021. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 113 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=uabr21 AJOB EMPIRICAL BIOETHICS https://doi.org/10.1080/23294515.2021.1907476 Absolutely Right and Relatively Good: Consequentialists See Bioethical Disagreement in a Relativist Light Hugo Vicianaa,b , Ivar R. Hannikainena,c , and David Rodrıguez-Ariasc aJuan de la Cierva Research Fellow, MICINN; bInstituto de Filosofıa, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientıficas, Madrid, Spain; cFiloLab-UGR Scientific Unit of Excellence, Departamento de Filosofıa I, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Background: Contemporary societies are rife with moral disagreement, resulting in recalci- Folk relativism; dissent and trant disputes on matters of public policy. In the context of ongoing bioethical controver- disputes; myside bias; sies, are uncompromising attitudes rooted in beliefs about the nature of moral truth? utilitarianism; argument evaluation; Spain Methods: To answer this question, we conducted both exploratory and confirmatory stud- ies, with both a convenience and a nationally representative sample (total N ¼ 1501), investi- gating the link between people’s beliefs about moral truth (their metaethics) and their beliefs about moral value (their normative ethics).