Creating the Craft of Tape Recording by John T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Jack Mullin/Bill Palmer Tape Restoration Project*

THETHE JACKJACK MULLIN/BILLMULLIN/BILL PPALMERALMER TTAPEAPE RESTORARESTORATIONTION PROJECPROJECTT** Richard L. Hess Glendale, California, USA hat do you do when you are entrusted him with some of the original to do: rise to the technical and logistical presented with three large German tapes that John T. (Jack) Mullin challenge. Wcartons of flangeless reels of and William A. (Bill) Palmer, a San The tapes arrived in three cardboard 50+-year-old tape? There is no meta- Francisco filmmaker, had used for a cartons that looked quite old. Inside was data,1 no list of contents, no tape speed, variety of purposes right after World an amazing array of packaging. As is no A or B wind information, no EQ War II. often the case in a restoration project, we curves—only tape. Where do you These tapes represent the earliest days had the old recordings and a modern begin? of magnetic recording in the United tape reproducer,3 but no knowledge of I recently found myself in this posi- States, including performances, either the original equipment used to tion. It all started innocently enough. As outtakes, and between-take banter by make the tapes or knowledge of the a member of the AES Los Angeles Bing Crosby, Dinah Shore, Peggy Lee, recording conventions common in the Section Committee, I had undertaken Burl Ives, and Claudette Colbert. late 1940s. Some of the initial chal- the organization of a program at one of Perhaps the gem of this collection is a lenges that presented themselves were: the Section’s monthly meetings. Also as portion of Bing Crosby’s 1947 • The tapes were on AEG (Allgemeine- a member of the AES Technical Christmas Eve show. -

Ampex Collection Addenda ARS.0109

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4v19s146 No online items Guide to the Ampex Collection Addenda ARS.0109 Finding aid prepared by Franz Kunst Archive of Recorded Sound Braun Music Center 541 Lasuen Mall Stanford University Stanford, California, 94305-3076 650-723-9312 [email protected] © 2011 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Ampex Collection ARS.0109 1 Addenda ARS.0109 Descriptive Summary Title: Ampex Collection Addenda Dates: 1944-1998 Collection number: ARS.0109 Repository: Archive of Recorded Sound Collection size: 1 box: 1 folder ; 17 open reel tapes (three 5" reels ; nine 7" reels ; four 10.5" reels ; one 12" reel) Abstract: Various smaller collections related to the Ampex Corporation, the development of magnetic recording on tape, and stereophonic sound. Access Open for research; material must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Contact the Archive for assistance. Publication Rights Property rights reside with repository. Publication and reproduction rights reside with the creators or their heirs. To obtain permission to publish or reproduce, please contact the Head Librarian of the Archive of Recorded Sound. Preferred Citation Ampex Collection Addenda, ARS-0109. Courtesy of the Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Sponsor This finding aid was produced with generous financial support from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. Related Collections Stanford University Special Collections holds the Ampex Corporation Records, M1230. The Archive of Recorded Sound holds the Richard Hess Mullin-Palmer Tape Restoration Project Collection, ARS.0035. Scope and Contents This is a group of small collections, assembled from various donors, related to the history of the Ampex Corporation and its role in the development of sound recording on tape and stereophonic sound. -

WWII to MP3 Society of Sound (416) 937-5826 Jack Mullin

THE AUDIO ENGINEERING SOCIETY B U L L E T I N www.torontoaes.org J UNE 2012 2011-2012 AES TORONTO EXECUTIVE Movie Presentation and Year End Social Chairman Robert DiVito Sound Man: WWII to MP3 Society of Sound (416) 937-5826 Jack Mullin Vice Chairman Frank Lockwood Lockwood ARS date Tuesday, 26 June 2012 (647) 349-6467 time 7:00 PM Recording Secretary Karl Machat where Ryerson University Mister’s Mastering RCC 204, Eaton Theatre, Rogers Communications Building House 80 Gould Street, Toronto, ON (416) 503-3060 Corner of Gould and Church, east of Yonge St (Dundas Subway) Treasurer Jeff Bamford Engineering For parking info and map, goto www.ryerson.ca/parking/ Harmonics (416) 465-3378 Pizza and refreshments will be provided Past Chair Sy Potma as part of our year end social. Fanshawe College, MIA (519) 452- This month’s meeting will NOT be available live on-line. 4430 x.4973 Membership Blair Francey Music Marketing Inc From 1877, with the birth of Edison’s cylinder phonograph, how much time 416-789-6848 elapsed before home audio achieved today’s quality? How good was magnetic tape recording in the U.S. in 1948? Who built the first magnetic Bulletin Editor Earl McCluskie Chestnut Hall Music videotape recorder? (519) 894-5308 Learn the answers to these and other historical puzzles and see firsthand Committee Members on DVD the growth of entertainment technology as we present Sound Keith Gordon Dan Man: WWII to MP3. VitaSound Audio Mombourquette DM Services (519) 696-8950 Sound Man: WWII to MP3 Advisors/Contributing Members Director: Don Hardy Jr. -

Der Bingle Technology

Der Bingle Technology by Steve Schoenherr No revolution has shaped the modern mass media more profoundly than the recording revolution. To record is the ability to create an exact duplicate of an act of communication, to preserve and replicate this act quickly and cheaply, and distribute countless copies of this act to consumers everywhere, so they can replay it over and over whenever they so desire. Johannes Gutenburg birthed the revolution in 1454 with his movable-type printing press. Louis Daguerre used chemistry to permanently fix a photographic image in 1839 and William Fox Talbot replicated positive prints from a single negative.Thomas Edison added the recordability of sounds in 1877 with his phonograph and of motion in 1893 with his kinetoscope. The man who would have the greatest impact on the mass media in the 20th century was not an inventor or scientist, but a crooner. A crooner, you say? Yes, it was Bing Crosby who was the leader of the revolution. The 1600 records he made during his 51-year career as a pop singer have never been equaled in number or influence. Bing sold 500 million copies during his career and only Elvis would sell more. His White Christmas was the No. 1 recorded song in total sales (35+ million) for over 50 years. He sang on 4000 radio shows from 1931 to 1962 and was the top-rated radio star for 18 of those years. He appeared in 100 movies and was the first popular singer to win a Academy Award for Best Actor (Going My Way, in 1944). -

Richard Hess Mullin-Palmer Tape Restoration Project Collection ARS.0035

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5k4036nc No online items Guide to The Richard Hess Mullin-Palmer Tape Restoration Project Collection ARS.0035 Finding aid prepared by Franz Kunst Archive of Recorded Sound Braun Music Center 541 Lasuen Mall Stanford University Stanford, California, 94305-3076 650-723-9312 [email protected] © 2009 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Guide to The Richard Hess ARS.0035 1 Mullin-Palmer Tape Restoration Project Collection ARS.... Descriptive Summary Title: Richard Hess Mullin-Palmer Tape Restoration Project Collection Dates: 1934-2008 Dates: Bulk, 1946-1950 Collection number: ARS.0035 Creator: Hess, Richard L. Collection Size: 6 linear feet: 110 digital files ; 54 open reel tapes Physical Description: Six boxes of audiotape are held by the Archive of Recorded Sound. The remainder of the collection is digital. Repository: Archive of Recorded Sound Abstract: Tapes and digitally transferred files from the early years of American tape recording. Transfers were done by engineer and researcher Richard L. Hess. Digital files are only available at Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound. Language of Material: English Access Open for research; material must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Contact the Archive for assistance. Publication Rights Property rights reside with repository. Literary rights reside with creators of the documents or their heirs. To obtain permission to publish or reproduce, contact the Head Librarian of the Archive of Recorded Sound. Preferred Citation Richard Hess Mullin-Palmer Tape Restoration Project Collection, ARS0035. Courtesy of the Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. -

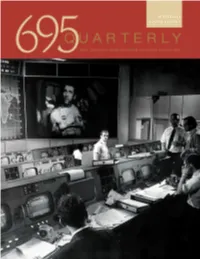

WINTER 2010 VOLUME 2 ISSUE 1 Table of QUARTERLY Contents 695 Volume 2 Issue 1

WINTER 2010 VOLUME 2 ISSUE 1 Table of QUARTERLY Contents 695 Volume 2 Issue 1 18 20 22 Features Departments 46th Annual CAS Award Nominees ..................... 10 From the Editors & Business Representative ..........4 Tech Emmy ..................................................................14 From the President ......................................................5 Goodin and Abrams honored News & Announcements ............................................6 Cat 5 .............................................................................15 Production Tracking Database Is there anything it can’t do? Education & Training ....................................................8 Inventions & Innovations .......................................... 18 Preparing for the demands of production The 24-frame video playback DISCLAIMER: I.A.T.S.E. LOCAL 695 and IngleDodd Publishing have used their best Smart Cart ................................................................... 20 efforts in collecting and preparing material for inclusion in the 695 Quarterly Magazine but Replacing the four-wheel Gator cannot warrant that the information herein is complete or accurate, and do not assume, and hereby disclaim, any liability to any person for any loss or damage caused by errors or omissions in the 695 Quarterly Magazine, whether such errors or omissions result Zaxcom 992 ................................................................ 22 from negligence, accident or any other cause. Further, any responsibility is disclaimed for changes, additions, -

William A. Palmer (1911-1996): Audio & Film Inventor and Filmmaker

WILLIAM A. PALMER (1911-1996): AUDIO & FILM INVENTOR AND FILMMAKER Veteran San Francisco filmmaker, inventor, and audio recording pioneer Bill Palmer died of a stroke on Thursday, 6 June 1996, at his home in Menlo Park, California, at the age of 85. Palmer founded W.A. Palmer & Co. in San Francisco in 1936, later renamed W.A. Palmer Films, Inc., a business over which he actively presided until his death. Working with Bing Crosby, ABC, and Ampex just after World War II, Palmer was the essential catalyst that began the era of high-quality audio magnetic tape recording in America. Palmer and his colleague, John T. (Jack) Mullin of San Francisco, perfected an American version of the German "Magnetophon" high-fidelity audio tape recorder in 1946. A memorable Palmer-Mullin demonstration of their magnetic recorders at the MGM studios in Hollywood in October, 1946, grabbed the town's attention with a stunningly clear recording of a studio performance by Jose Iturbi, George E. Stoll and the MGM Symphony Orchestra. The new medium was demonstrably superior to the then-new method of optical film recording for the production of film sound tracks, the MGM 200-mil push-pull system. In just one year, Palmer and Mullin took audio recording from "poor" by today's standards to contemporary analog quality. A critical listening test of the early MGM and Bing Crosby recordings made on the modified Magnetophons reveals sonic quality perfectly acceptable for any network or local FM broadcast today. Using the Mullin-Palmer tape machines in 1946, Merv Griffin in San Francisco was the first U.S. -

The History of NBC West Coast Studios

1 The History Of NBC West Coast Studios By Bobby Ellerbee and Eyes Of A Generation.com Preface and Acknowledgement This is a unique look at the events that preceded the need for NBC television studios in Hollywood. As in New York, the radio division led the way. This project is somewhat different than the prior reports on the New York studios of NBC and CBS for two reasons. The first reason is that in that in those reports, television was brand-new and being developed through the mechanical function to an electronic phenomenon. Most of that work occurred in and around the networks’ headquarters in New York. In this case, both networks were at the mercy of geological and technological developments outside their own abilities: the Rocky Mountains and AT&T. The second reason has to do with the success of the network’s own stars. Their popularity on radio soon translated to public demand once “talking pictures” became possible. That led many New York based radio stars to Hollywood and, in a way, Mohamed had to come to the mountain. This story is told to the best of our abilities, as a great deal of the information on these facilities is now gone…like so many of the men and women who worked there. I’ve told this as concisely as possible, but some elements are dependent on the memories of those who were there many years ago, and from conclusions drawn from research. If you can add to this with facts or photos, please contact me as this is an ongoing project. -

Santa Clara Magazine Volume 48 Number 1, Summer 2006 Santa Clara University

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Santa Clara Magazine SCU Publications 2006 Santa Clara Magazine Volume 48 Number 1, Summer 2006 Santa Clara University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/sc_mag Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Business Commons, Education Commons, Engineering Commons, Law Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Santa Clara University, "Santa Clara Magazine Volume 48 Number 1, Summer 2006" (2006). Santa Clara Magazine. Book 18. http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/sc_mag/18 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the SCU Publications at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Magazine by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V OLUME 48 N UMBER 1 Magazine SantaPublished for the Alumni and Friends of SantaClara Clara University Summer 2006 Three Roommates in Paris At the University of Paris in 1529, Pierre Favre, Francisco Xavier, and In˜igo de Loyola shared a room. Out of this relationship, the Society of Jesus was born. Page 14 PHOTO: CHARLES BARRY CHARLES BARRY PHOTO: Jack Mullin ’36 Biodiversity: Jill Mason ’99 8 and the art of 20 Who cares? 30 is back from sound the brink sscm_1205258_Sum06_r4.1.inddcm_1205258_Sum06_r4.1.indd C 44/25/06/25/06 44:40:11:40:11 PPMM from the editor This is my last letter to you. I have enjoyed my Dear Readers: brief stint as acting editor. And I have certainly acquired a huge respect for magazine editors everywhere. -

Principles of Magnetic Recording

Chapter 6.1 Principles of Magnetic Recording E. Stanley Busby 6.1.1 Introduction Magnetic recording enjoys a rich history. The Danish inventor Valdemar Poulsen made the first magnetic sound recorder when, in 1898, he passed the current from a telephone through a recording head held against a spiral of steel wire wound on a brass drum. Upon playback, the magnetic variations in the wire induced enough voltage in the head to power a telephone receiver. Amplification was not available at the time. The hit of the Paris Exposition of 1900, Poulsen’s recorder won the grand prize. In this mag- netic analog of Edison’s acoustic recorder (which impressed a groove on a rotating tinfoil-cov- ered drum), one whole cylinder held only 30 s of sound. In a few years, the weak and highly distorted output of Poulsen’s device was vastly improved by adding a fixed magnetizing current, called bias, to the output of the telephone. This centered the signal current variations on the steepest part of the curve of remanent magnetism, greatly improving the gain and linearity of the system. In 1923, two researchers working for the U.S. Navy first applied high-frequency ac bias. This eliminated even-order distortion, greatly reduced the noise induced by the surface roughness of the medium, and improved the amplitude of the recovered signal. Except in some toys, ac bias is used in all audio recorders. Wire recording, further developed in the United States, found wide use during World War I1 and entered the home recording market by the late 1940s. -

Jack Mullin with Ampex Model 200, Which Revolutionized The

Just after World War 11, Mullin introduced Bing Crosby to tape recording, a move that boosted the performer's career. Working with Bing Crosby Enterprises, U.S. broad- casters, and manufacturers, including Ampex in Redwood City, Mullin was instrumental in helping launch high- quality audio magnetic tape recording in America. He also built the first suc- cessful prototype of a video tape recorder (VTR), which led to the commercial VTR for television broadcasters, the forerunner of to- day's consumer VCR. In 1946, Mullin redesigned and im- proved his two German Magne- tophons with financial and mechani- cal engineering assistance from his partner, W. A. Palmer, a pioneer film- maker. Mullin and Palmer created new methods for producing high-fi- delity sound on 16-mm film using "wild"(unsynchronized) magnetic tape, a first in the U.S. The Mullin- Jack Mullin with Ampex Model 200, which revolutionized Palmer Magnetophons were used to the entertainment and ~nformationindustries. produce the first American commer- cial entertainment disc professionally mastered on tape, "Songs by Merv Griffin," released in 1946. The first ohn T. (Jack) Mullin, audio and broadcasting. Mullin reasoned the public demonstration of hi-fi tape, on video engineer, and honorary Germans had some kind of outstand- May 16, 1946 in San Francisco, JAES member, died of heart fail- ing, new recording technology. stunned the audience of engineers, ure on Thursday, June 24, at his home In Paris, starting in the late summer who could not believe they were not in Carnarillo, Califomia, at the age of .of. 1994, Mullin's missjon was to ex- hearing live music. -

Santa Clara Magazine Volume 48 Number 1, Summer 2006 Santa Clara University

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Santa Clara Magazine SCU Publications Summer 2006 Santa Clara Magazine Volume 48 Number 1, Summer 2006 Santa Clara University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/sc_mag Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Business Commons, Education Commons, Engineering Commons, Law Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Santa Clara University, "Santa Clara Magazine Volume 48 Number 1, Summer 2006" (2006). Santa Clara Magazine. 18. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/sc_mag/18 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the SCU Publications at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Magazine by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V OLUME 48 N UMBER 1 Magazine SantaPublished for the Alumni and Friends of SantaClara Clara University Summer 2006 Three Roommates in Paris At the University of Paris in 1529, Pierre Favre, Francisco Xavier, and In˜igo de Loyola shared a room. Out of this relationship, the Society of Jesus was born. Page 14 PHOTO: CHARLES BARRY CHARLES BARRY PHOTO: Jack Mullin ’36 Biodiversity: Jill Mason ’99 8 and the art of 20 Who cares? 30 is back from sound the brink sscm_1205258_Sum06_r4.1.inddcm_1205258_Sum06_r4.1.indd C 44/25/06/25/06 44:40:11:40:11 PPMM from the editor This is my last letter to you. I have enjoyed my Dear Readers: brief stint as acting editor. And I have certainly acquired a huge respect for magazine editors everywhere.