Question and Answers: Cephas-Peter; Similarities With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F.F. Bruce, "Some Notes on the Fourth Evangelist,"

F.F. Bruce, “Some Notes on the Fourth Evangelist,” The Evangelical Quarterly 16 (1944): 101-109. Some Notes on the Fourth Evangelist F.F. Bruce [p.101] I. THE WITNESS OF PAPIAS In the preface to his five books of Exegesis of the Dominical Oracles (ap. Euseb. HE iii. 39), Papias says: “If ever anyone came who had kept company with the Elders, I would inquire about the words of the Elders: ‘What did Andrew or Peter, or Philip or Thomas or James, or John or Matthew or any other of the Lord’s disciples say? And what do Aristion and the Elder John, the Lord’s disciples, say?’” Most scholars to-day, following Eusebius, find two Johns in the fragment, and they may be right. Eusebius, to be sure, had an axe to grind, for he was glad to find a possible non-- apostolic author for the Apocalypse; but this cannot be said of such impartial scholars as Tregelles and Lightfoot, who also distinguished two Johns here. But the question is by no means closed. Against Tregelles and Lightfoot might be quoted Salmon and Zahn. Lawlor and Oulton, in their edition of Eusebius (1928), say in their note on this passage (Vol. ii. p. 112,): “But the reasoning of Eusebius seems unconvincing: and the argument of others who have reached the same conclusion on other lines is of doubtful validity (e.g. Schmiedel in Encyc. Bib., 2506ff.; Harnack, Chron. i. 660ff.).” And Professor C. J. Cadoux, who will not be suspected of conservative bias, writes in Ancient Smyrna (1938), p. -

Barnabas, His Gospel, and Its Credibility Abdus Sattar Ghauri

Reflections Reflections Barnabas, His Gospel, and its Credibility Abdus Sattar Ghauri The name of Joseph Barnabas has never been strange or unknown to the scholars of the New Testament of the Bible; but his Gospel was scarcely known before the publication of the English Translation of ‘The Koran’ by George Sale, who introduced this ‘Gospel’ in the ‘Preliminary Discourse’ to his translation. Even then it remained beyond the access of Muslim Scholars owing to its non-availability in some language familiar to them. It was only after the publication of the English translation of the Gospel of Barnabas by Lonsdale and Laura Ragg from the Clarendon Press, Oxford in 1907, that some Muslim scholars could get an approach to it. Since then it has emerged as a matter of dispute, rather controversy, among Muslim and Christian scholars. In this article it would be endeavoured to make an objective study of the subject. I. BRIEF LIFE-SKETCH OF BARNABAS Joseph Barnabas was a Jew of the tribe of Levi 1 and of the Island of Cyprus ‘who became one of the earliest Christian disciples at Jerusalem.’ 2 His original name was Joseph and ‘he received from the Apostles the Aramaic surname Barnabas (...). Clement of Alexandria and Eusebius number him among the 72 (?70) disciples 3 mentioned in Luke 10:1. He first appears in Acts 4:36-37 as a fervent and well to do Christian who donated to the Church the proceeds from the sale of his property. 4 Although he was Cypriot by birth, he ‘seems to have been living in Jerusalem.’ 5 In the Christian Diaspora (dispersion) many Hellenists fled from Jerusalem and went to Antioch 6 of Syria. -

Daily Discipleship

Luke 10:1-11, 16-20 July 3, 2016 Stories of Discipleship: A Harvester’s Story Focus Question: What are the joys and frustrations of harvesting for God’s kingdom? word of life “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few; therefore ask the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest.” Luke 10:2 (NRSV) Read Luke 10:1-11, 16-20 Jesus is on a mission. Time is getting short and there is so much to do. In Luke 9, Jesus predicts his own death and challenges would-be followers about the difficulties ahead. In Luke 10, Jesus appoints seventy disciples and sends them off by twos. These teams of two are to go to the villages and make preparations for Jesus to visit. Thirty-five teams is an impressive number of ambassadors to be dispersed for Jesus. 1. What would it have been like to be on one of those teams? 2. Why send so many teams? The seventy are no longer to be in the background, listening to Jesus. Like John the Baptist, the seventy are being asked to prepare the way for Jesus. Each person might be asked to speak clearly about the Messiah. Jesus is in the process of training his disciples and passing on the mission. It is an exciting transition, but these disciples are not to rely on their own abilities. “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few; therefore ask the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest.” (Luke 10:2 NRSV) 3. -

A:Cts of the Apostles (Revised Version)

THE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE EDITION. A:CTS OF THE APOSTLES (REVISED VERSION) (CHAPTERS I.-XVI.) WITH BY THK REV. F. MARSHALL, M.A., (Lau Ezhibition,r of St, John's College, Camb,idge)• Recto, of Mileham, formerly Principal of the Training College, Ca11narthffl. and la1ely Head- Master of Almondbury Grammar School, First Edition 1920. Ten Impressions to 1932. Jonb.on: GEORGE GILL & SONS, Ln., MINERVA HOUSE, PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.4. MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ACTS OPTBE APOSTLES . <t. ~ -li .i- C-4 l y .A. lO 15 20 PREFACE. 'i ms ~amon of the first Sixteen Chapters of the Acts of the Apostles is intended for the use of Students preparing for the Local Examina tions of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and similar examinations. The Syndicates of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities often select these chapters as the subject for examination in a particular year. The Editor has accordingly drawn up the present Edition for the use of Candidates preparing for such Examinations. The Edition is an abridgement of the Editor's Acts of /ht Apostles, published by Messrs. Gill and Sons. The Introduction treats fully of the several subjects with which the Student should be acquainted. These are set forth in the Table of Contents. The Biographical and Geographical Notes, with the complete series of Maps, will be found to give the Student all necessary information, thns dispensing with the need for Atlas, Biblical Lictionary, and other aids. The text used in this volume is that of the Revised Version and is printed by permission of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but all editorial responsibility rests with the editor of the present volume. -

'Incident at Antioch': Chrysostom on Galatians 2:11-14

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Portal Apostolic authority and the ‘incident at Antioch’: Chrysostom on Galatians 2:11-14 Griffith, Susan B License: Creative Commons: Attribution-NoDerivs (CC BY-ND) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Griffith, SB 2017, Apostolic authority and the ‘incident at Antioch’: Chrysostom on Galatians 2:11-14. in Studia Patristica: Papers presented at the Seventeenth International Conference on Patristic Studies held in Oxford 2015. vol. 96, Studia Patristica, vol. 96, Peeters, Leuven, Belgium, pp. 117-126, Seventeenth International Conference on Patristic Studies, Oxford, United Kingdom, 10/08/15. Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Open access fees paid by COMPAUL project in 2016. General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

Growth Hour Study Spiritual Warfare 3 Luke 10:1-24; Ephesians 6:10-20 Sept

Growth Hour Study Spiritual Warfare 3 Luke 10:1-24; Ephesians 6:10-20 Sept. 8, 2019 ENGAGE This week we are looking at Luke 10:1-24 and Ephesians 6:10-20 The 72 are sent out, just as you and I are sent out, and Jesus speaks about authority and identity. My focus on Sunday will be that our authority is found in our identity with Christ. The armor of God is a picture of our identity in Christ as we face the enemy through life. The study below has many questions. My suggestion is to go through the questions and highlight one or two from each segment of the Luke passage that you will ask on Sunday. I have given you information for the Ephesians passage for your benefit. I will be preaching mostly from the Ephesians passage. If you focus on the sending of the 72 (all of us) and the authority we have in our identity in Christ, that should be beneficial for the Body as they come into worship service. Blessings to you all. EXAMINE Luke 10:1-24 A. Instructing the seventy disciples at their departure. 1. (Luke 10:1-3) Seventy disciples are appointed and sent out. After these things the Lord appointed seventy others also, and sent them two by two before His face into every city and place where He Himself was about to go. Then He said to them, "The harvest truly is great, but the laborers are few; therefore pray the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into His harvest. -

SYNAXARION, COPTO-ARABIC, List of Saints Used in the Coptic Church

(CE:2171b-2190a) SYNAXARION, COPTO-ARABIC, list of saints used in the Coptic church. [This entry consists of two articles, Editions of the Synaxarion and The List of Saints.] Editions of the Synaxarion This book, which has become a liturgical book, is very important for the history of the Coptic church. It appears in two forms: the recension from Lower Egypt, which is the quasi-official book of the Coptic church from Alexandria to Aswan, and the recension from Upper Egypt. Egypt has long preserved this separation into two Egypts, Upper and Lower, and this division was translated into daily life through different usages, and in particular through different religious books. This book is the result of various endeavors, of which the Synaxarion itself speaks, for it mentions different usages here or there. It poses several questions that we cannot answer with any certainty: Who compiled the Synaxarion, and who was the first to take the initiative? Who made the final revision, and where was it done? It seems evident that the intention was to compile this book for the Coptic church in imitation of the Greek list of saints, and that the author or authors drew their inspiration from that work, for several notices are obviously taken from the Synaxarion called that of Constantinople. The reader may have recourse to several editions or translations, each of which has its advantages and its disadvantages. Let us take them in chronological order. The oldest translation (German) is that of the great German Arabist F. Wüstenfeld, who produced the edition with a German translation of part of al-Maqrizi's Khitat, concerning the Coptic church, under the title Macrizi's Geschichte der Copten (Göttingen, 1845). -

Weekly Schedule

Assumption of the Holy Virgin Orthodox Church 2101 South 28th St. (corner of 28th St. & Snyder Ave.) Philadelphia, PA 19145 * Church Phone: (215) 468-3535 Website: http://www.holyassumptionphilly.org http://www.facebook.com/holyassumptionphilly Mailing Address: PO Box 20083 * Point Breeze Station | Philadelphia PA 19145-0383 Sunday, August 21, 2016 | 9th Sunday After Pentecost Tone 8 –Afterfeast of the Dormition. Apostle Thaddeus of the Seventy (ca. 44 A.D.) Martyr Bassa (Vassa) of Edessa and her sons (2nd c.) V. Rev. Mark W Koczak, Acting Rector 615 West 11th Street | New Castle, DE 19720-6020 Phone: Home: 302-322-0943 | Mobile: 302-547-4952 Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Parish President – Matthew Andrews Phone: 856-217-8075 Weekly Schedule Today: Philadelphia Orthodox Clergy Brotherhood Service of Supplication to the Theotokos (Akathist) - 4:00PM St. Nicholas Serbian Orthodox Church 506 Stahr Road – Elkins Park, PA 19027 Phone: 215.782.8448 Website: www.stnicholasphilly.com Saturday: August 27 – NO Great Vespers on this day! Sunday: August 28 – Uncovering Relics of Ven. Job; Ven. Moses the Black of Scete Reading of Hours – 9:30am Divine Liturgy – 10:00am Fellowship & coffee hour to follow the Divine Liturgy 1 Texts for the Liturgical Service Troparion (Tone 8) Thou didst descend from on high, O Merciful One! / Thou didst accept the three day burial / to free us from our sufferings! // O Lord, our Life and Resurrection, glory to Thee! Troparion (Tone 1 – Dormition) In giving birth thou didst preserve thy virginity. / In falling asleep thou didst not forsake the world, O Theotokos. -

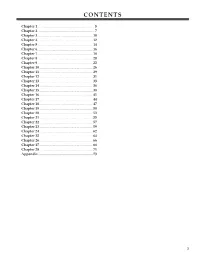

Student Guide Sample

CONTENTS Chapter 1 ............................................................................................. 5 Chapter 2 ............................................................................................. 7 Chapter 3 .......................................................................................... 10 Chapter 4 .......................................................................................... 12 Chapter 5 .......................................................................................... 14 Chapter 6 .......................................................................................... 16 Chapter 7 .......................................................................................... 18 Chapter 8 .......................................................................................... 20 Chapter 9 .......................................................................................... 23 Chapter 10 ....................................................................................... 26 Chapter 11 ....................................................................................... 29 Chapter 12 ....................................................................................... 31 Chapter 13 ....................................................................................... 33 Chapter 14 ....................................................................................... 36 Chapter 15 ....................................................................................... 38 -

“And Joses, Who by the Apostles Was Surnamed Barnabas, (Which Is

Sunday, March 21, 2010 Sermon Outline…page 1 “And Joses, who by the apostles was surnamed Barnabas, (which is, being interpreted, The son of consolation,) a Levite, and of the country of Cyprus, Having land, sold it, and brought the money, and laid it at the apostles’ feet.” Acts 4:36,37. In this unique way the Holy Spirit introduces God’s Elect throughout the ages to Barnabas, whom the Holy Ghost elsewhere calls, “a good man, and full of the Holy Ghost and of faith;” to wit: “Now they which were scattered abroad upon the persecution that arose about Stephen traveled as far as Phenice, and Cyprus, and Antioch, preaching the word to none but unto the Jews only. And some of them were men of Cyprus (think, Joses, surnamed Barnabas) and Cyrene, which, when they were come to Antioch, spake unto the Grecians, preaching the Lord Jesus. And the hand of the Lord was with them; and a great number believed, and turned unto the Lord. Then tidings of these things came unto the ears of the church which was in Jerusalem; and they sent forth BARNABAS, that he should go as far as Antioch. Who, when he came, and had seen the grace of God, was glad, and exhorted them all, that with purpose of heart they would cleave unto the Lord. FOR HE WAS A GOOD MAN, AND FULL OF THE HOLY GHOST AND OF FAITH; and much people was added unto the Lord. Then departed BARNABAS to Tarsus, for to seek Saul. And when he had found him, he brought him unto Antioch. -

S T M a R Y ' S C a T H O L I C C H U R C H – 2

S T M A R Y ’ S C A T H O L I C C H U R C H – 2 2 8 E A S T J E F F E R S O N S T R E E T – I O W A C I T Y I O W A 5 2 2 4 5 ST MARY OF THE VISITATION CATHOLIC CHURCH SACRED ART KEY MAIN ALTAR 1 ST ANNE (WITH MARY) (1st cent. B.C.-1st cent A.D.) Patron saint of housewives and women in labor JUL 26TH She was Mary’s mother, wife of St. Joachim, and grandmother to Jesus -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 THE VISITATION Mary visits her cousin, Elizabeth (mother of John the Baptist) (Luke 1:39-56) MAY 31ST "Blessed is she who believed that what was spoken to her by the Lord would be fulfilled" -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 ST PATRICK (5th cent.-c.493) Patron saint of Ireland, Nigeria, and engineers MAR 17TH He promulgated the Christian faith in Ireland -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 ST BONIFACE (675-754) Patron -

The Secret Tradition

Margaret Barker The Secret Tradition First published in the Journal of Higher Criticism 2.1 1995 pp.31-67. This present version has some corrections and additions to the references [author’s note].1 ‘This is the kind of divine enlightenment into which we have been initiated by the hidden tradition of our inspired teachers, a tradition at one with Scripture. We now grasp these things in the best way we can, and as they come to us, wrapped in the sacred veils of that love toward humanity with which scripture and hierarchical traditions cover the truths of the mind with things derived from the realm of the senses.’ Dionysius On the Divine Names 5992B ‘But see to it that you do not betray the Holy of Holies. Let your respect for the things of the hidden God be shown in knowledge that comes from the intellect and is unseen. Keep these things of God unshared and undefiled by the uninitiated.’ Dionysius The Ecclesiastical Hierachy 372A There was far more to the teaching of Jesus than is recorded in the canonical gospels. For several centuries a belief persisted among Christian writers that there had been a secret tradition entrusted to only a few of his followers. Eusebius quotes from a now lost work of Clement of Alexandria, Hypotyposes: ‘James the Righteous, John and Peter were entrusted by the LORD after his resurrection with the higher knowledge. They imparted it to the other apostles, and the other apostles to the seventy, one of whom was Barnabas.’ (History 2.1) This brief statement offers three important pieces of evidence: the tradition was given to an inner circle of disciples; the tradition was given after the resurrection; and the tradition was a form of higher knowledge i.e.