Don't Let Them Silence Taslima Nasreen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ssc Special Daily Quiz -740 Total Questions-40, Time - 40 Minutes, Marks - 40 Arena of General Knowledge 1

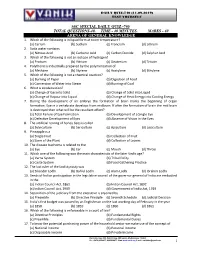

DAILY QUIZ-740 (11.09.2019) TEST YOURSELF SSC SPECIAL DAILY QUIZ -740 TOTAL QUESTIONS-40, TIME - 40 MINUTES, MARKS - 40 ARENA OF GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. Which of the following is in liquid form at room temperature? (a) Cerium (b) Sodium (c) Francium (d) Lithium 2. Soda water contains (a) Nitrous Acid (b) Carbonic Acid (c) Carbon Dioxide (d) Sulphur Acid 3. Which of the following is not an isotope of hydrogen? (a) Protium (b) Yttrium (c) Deuterium (d) Trituim 4. Polythene is industrially prepared by the polymerization of (a) Methane (b) Styrene (c) Acetylene (d) Ethylene 5. Which of the following is not a chemical reaction? (a) Burning of Paper (b) Digestion of Food (c) Conversion of Water into Steam (d) Burning of Coal 6. What is condensation? (a) Change of Gas into Solid (b) Change of Solid into Liquid (c) Change of Vapour into Liquid (d) Change of Heat Energy into Cooling Energy 7. During the development of an embryo the formation of brain marks the beginning of organ formation. Eye in a vertebrate develops from midbrain. If after the formation of brain the mid brain is destroyed then what will be the resultant effect? (a) Total Failure of Eye Formation (b) Development of a Single Eye (c) Defective Development of Eyes (d) Absence of Vision in the Eyes 8. The artificial rearing of honey bees is called (a) Sylviculture (b) Sericulture (c) Apiculture (d) Lociculture 9. Pineapple is a (a) Single Fruit (b) Collection of Fruit (c) Stem of the Plant (d) Collection of Leaves 10. The disease trachoma is related to the (a) Eye (b) Ear (c) Mouth (d) Throat 11. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

Khushwantnama -The Essence of Life Well- Lived

Dr. Sunita B. Nimavat [Subject: English] International Journal of Vol. 2, Issue: 4, April-May 2014 Research in Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN:(P) 2347-5404 ISSN:(O)2320 771X Khushwantnama -The Essence of Life Well- Lived DR. SUNITA B. NIMAVAT N.P.C.C.S.M. Kadi Gujarat (India) Abstract: In my research paper, I am going to discuss the great, creative journalist & author Khushwant Singh. I will discuss his views and reflections on retirement. I will also focus on his reflections regarding journalism, writing, politics, poetry, religion, death and longevity. Keywords: Controversial, Hypocrisy, Rejects fundamental concepts-suppression, Snobbish priggishness, Unpalatable views Khushwant Singh, the well known fiction writer, journalist, editor, historian and scholar died at the age of 99 on March 20, 2014. He always liked to remain controversial, outspoken and one who hated hypocrisy and snobbish priggishness in all fields of life. He was born on February 2, 1915 in Hadali now in Pakistan. He studied at St. Stephen's college, Delhi and king's college, London. His father Shobha Singh was a prominent building contractor in Lutyen's Delhi. He studied law and practiced it at Lahore court for eight years. In 1947, he joined Indian Foreign Service and worked under Krishna Menon. It was here that he read a lot and then turned to writing and editing. Khushwant Singh edited ‘ Yojana’ and ‘ The Illustrated Weekly of India, a news weekly. Under his editorship, the weekly circulation rose from 65000 copies to 400000. In 1978, he was asked by the management to leave with immediate effect. -

Afrindian Fictions

Afrindian Fictions Diaspora, Race, and National Desire in South Africa Pallavi Rastogi T H E O H I O S TAT E U N I V E R S I T Y P R E ss C O L U MB us Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rastogi, Pallavi. Afrindian fictions : diaspora, race, and national desire in South Africa / Pallavi Rastogi. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-0319-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-0319-1 (alk. paper) 1. South African fiction (English)—21st century—History and criticism. 2. South African fiction (English)—20th century—History and criticism. 3. South African fic- tion (English)—East Indian authors—History and criticism. 4. East Indians—Foreign countries—Intellectual life. 5. East Indian diaspora in literature. 6. Identity (Psychol- ogy) in literature. 7. Group identity in literature. I. Title. PR9358.2.I54R37 2008 823'.91409352991411—dc22 2008006183 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–08142–0319–4) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–08142–9099–6) Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Typeset in Adobe Fairfield by Juliet Williams Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the Ameri- can National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction Are Indians Africans Too, or: When Does a Subcontinental Become a Citizen? 1 Chapter 1 Indians in Short: Collectivity -

M Nurul Islam Executive Editor Sk Hafizur Rahman Associate Editors Najib Anwar Ekramul Haque Shaikh Graphics Md Golam Kibriya

Al-AmeenZ Mission Advisors Ekram Ali Prof Rafikul Islam Dr Sk Md Hassan Editor M Nurul Islam Executive Editor Sk Hafizur Rahman Associate Editors Najib Anwar Ekramul Haque Shaikh Graphics Md Golam Kibriya Published by M Nurul Islam from 53B Elliot Road, Kolkata 700 016 on behalf of Al- Ameen Mission Trust and printed at Diamond Art Press, 37/A Bentinck Street, Kolkata 700 069. Ph: 033-3297 3580 Fax: 033-2229 3769 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.alameenmission.in facebook.com/alameenmission.newsletter (M Nurul Islam) A R C H I V E School Bells Echo Amidst Paddy Fields In 1986, Nurul Islam set up a hostel with 11 students, collecting one fist of rice from every home in his village, Khalatpur. In January 1987, it was named as Al-Ameen Mission which has today become a model for excellent education standards. By A Staff Reporter are over 300 students following the West Bengal Council of Higher Secondary Education syllabus. The Al-Ameen In a country like India, we cannot leave the less privileged Mission receives over 6000 applications for admissions to the merciless hands of the market forces. The solution from the whole of West Bengal. The admission test is to this problem perhaps lies somewhere, far away from held at 28 centres. The students go through a pre-se- the issue of reservations in higher education that is ter- lection exam, an interview and a test of reasoning. The ribly resented by the more meritorious. In a village called intake of students for the campus is around 500 to 600. -

Name Fname Rollno Aarti Devi Amar Singh 551011 Ajay Nand Kishor

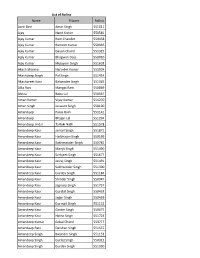

List of Rollno Name FName Rollno Aarti Devi Amar Singh 551011 Ajay Nand Kishor 550581 Ajay Kumar Ram Chander 550458 Ajay Kumar Ramesh Kumar 550336 Ajay Kumar Gayan Chand 551315 Ajay Kumar Bhagwan Dass 550010 Ajay Kumar Mulayam Singh 551603 Akash Sharma Narinder Kumar 551904 Akashdeep Singh Pal Singh 551414 Akashpreet Kaur Balwinder Singh 551365 Alka Rani Mangat Ram 550869 Alvina Babu Lal 550561 Aman Kumar Vijay Kumar 551270 Aman Singh Jaswant Singh 550190 Amandeep Paras Ram 551141 Amandeep Bhajan Lal 551294 Amandeep Jindal Tarloki Nath 551578 Amandeep Kaur Jarnail Singh 551871 Amandeep Kaur Harbhajan Singh 550169 Amandeep Kaur Sukhmander Singh 550781 Amandeep Kaur Manjit Singh 551490 Amandeep Kaur Sarbjeet Singh 551677 Amandeep Kaur Jasraj Singh 551491 Amandeep Kaur Sukhwinder Singh 551300 Amandeep Kaur Gurdev Singh 551184 Amandeep Kaur Shinder Singh 550347 Amandeep Kaur Jagroop Singh 551737 Amandeep Kaur Gurdial Singh 550453 Amandeep Kaur Jagsir Singh 550459 Amandeep Kaur Gurmail SIngh 551122 Amandeep Kaur Ginder Singh 550675 Amandeep Kaur Natha Singh 551724 Amandeep Kumar Gokal Chand 550777 Amandeep Rani Darshan Singh 551537 Amandeep Singh Baljinder Singh 551153 Amandeep Singh Gurtej Singh 550312 Amandeep Singh Gurdev Singh 551030 List of Rollno Name FName Rollno Amandeep Singh Balwinder SIngh 550016 Amandeep Singh Surjeet Singh 551251 Amandeep Singh Subhash Singh 551637 Amandeep Singh Angraj Singh 551622 Amandeep Singh Gurcharan Singh 551596 Amandeep Singh Nathu Ram 550748 Amandeep Singh Jarnail Singh 550058 Amandeep Singh Shinder -

APPENDIX 1 a Full Text of the Interview with Gauri Deshpande Who Was A

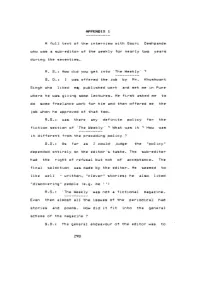

APPENDIX 1 A full text of the interview with Gauri Deshpande who was a sub-editor of the weekly for nearly two years during the seventies. R. S.: How did you get into The Weekly' ? G. D.: I was offered the job by Mr. Khushwant Singh who liked m«y published work and met me in Pune where he was giving some lectures. He first asked me to do some freelance work for him and then offered me the job when he approved of that too. R.S.: was there any definite policy for the fiction section of "The Weekly' ? What was it ? How was it different from the preceding policy ? B.D.: As far as I could judge the "policy" depended entirely on the editor's taste. The sub-editor had the right of refusal but not of acceptance. The final selection was made by the editor. He seemed to like well - written, "clever" stories; he also liked "discovering" people (e.g. me II) R.S.: 'The Weekly' was not a fictional magazine. Even then almost all the issues of the periodical had stories and poems. How did it fit into the general scheme of the magazine ? G.D.: The general endeavour of the editor was to 298 make 'The Weekly' into a brighter, more popular, more accessible paper; less 'colonial' if one can say that. The changes he made in typography, layout, covers, photographs, even payment scales, all point to this. The often controversial themes of his main photo features (e.g. communities of india) and the bright new look fiction were part of the general policy. -

The Partition of India Midnight's Children

THE PARTITION OF INDIA MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN, MIDNIGHT’S FURIES India was the first nation to undertake decolonization in Asia and Africa following World War Two An estimated 15 million people were displaced during the Partition of India Partition saw the largest migration of humans in the 20th Century, outside war and famine Approximately 83,000 women were kidnapped on both sides of the newly-created border The death toll remains disputed, 1 – 2 million Less than 12 men decided the future of 400 million people 1 Wednesday October 3rd 2018 Christopher Tidyman – Loreto Kirribilli, Sydney HISTORY EXTENSION AND MODERN HISTORY History Extension key questions Who are the historians? What is the purpose of history? How has history been constructed, recorded and presented over time? Why have approaches to history changed over time? Year 11 Shaping of the Modern World: The End of Empire A study of the causes, nature and outcomes of decolonisation in ONE country Year 12 National Studies India 1942 - 1984 2 HISTORY EXTENSION PA R T I T I O N OF INDIA SYLLABUS DOT POINTS: CONTENT FOCUS: S T U D E N T S INVESTIGATE C H A N G I N G INTERPRETATIONS OF THE PARTITION OF INDIA Students examine the historians and approaches to history which have contributed to historical debate in the areas of: - the causes of the Partition - the role of individuals - the effects and consequences of the Partition of India Aims for this presentation: - Introduce teachers to a new History topic - Outline important shifts in Partition historiography - Provide an opportunity to discuss resources and materials - Have teachers consider the possibilities for teaching these topics 3 SHIFTING HISTORIOGRAPHY WHO ARE THE HISTORIANS? WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF HISTORY? F I E R C E CONTROVERSY HAS RAGED OVER THE CAUSES OF PARTITION. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

Parliamentary Information

The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LVI NO. 4 DECEMBER 2010 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. 24. Ansari Road. Darya Ganj, New Delhi-2 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor T.K. Viswanathan Secretary-General Lok Sabha Associate Editor P.K. Misra Joint Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Assistant Editors Kalpana Sharma Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Pulin B. Bhutia Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Sanjeev Sachdeva Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat © Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUME LVI NO.4 DECEMBER 2010 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 375 AooResses Addresses at the Conferment of the Outstanding Parliamentarian Awards for the years 2007, 2008 and 2009, New Delhi, 18 August 2010 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Conferences and Symposia 394 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 397 Exchange of Partiamentary Delegations 398 Bureau of Parliamentary Studies and Training 400 PROCEDURAL MATTERS 401 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 405 DocuMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 414 SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha 426 Rajya Sabha 450 State Legislatures 469 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 4n APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Fifth Session of the Fifteenth Lok Sabha 481 II. Statement showing the work transacted during the Two Hundred and Twentieth Session of the Rajya Sabha 486 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union territories during the period 1 July to 30 September 2010 491 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and assented to by the President during the period 1 July to 30 September 2010 498 V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States and the Union territories during the period 1 July to 30 September 2010 499 VI. -

Static GK Capsule 2017

AC Static GK Capsule 2017 Hello Dear AC Aspirants, Here we are providing best AC Static GK Capsule2017 keeping in mind of upcoming Competitive exams which cover General Awareness section . PLS find out the links of AffairsCloud Exam Capsule and also study the AC monthly capsules + pocket capsules which cover almost all questions of GA section. All the best for upcoming Exams with regards from AC Team. AC Static GK Capsule Static GK Capsule Contents SUPERLATIVES (WORLD & INDIA) ...................................................................................................................... 2 FIRST EVER(WORLD & INDIA) .............................................................................................................................. 5 WORLD GEOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................................................ 9 INDIA GEOGRAPHY.................................................................................................................................................. 14 INDIAN POLITY ......................................................................................................................................................... 32 INDIAN CULTURE ..................................................................................................................................................... 36 SPORTS ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Padma Vibhushan * * the Padma Vibhushan Is the Second-Highest Civilian Award of the Republic of India , Proceeded by Bharat Ratna and Followed by Padma Bhushan

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Padma Vibhushan * * The Padma Vibhushan is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India , proceeded by Bharat Ratna and followed by Padma Bhushan . Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service", without distinction of race, occupation & position. Year Recipient Field State / Country Satyendra Nath Bose Literature & Education West Bengal Nandalal Bose Arts West Bengal Zakir Husain Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh 1954 Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher Public Affairs Maharashtra V. K. Krishna Menon Public Affairs Kerala Jigme Dorji Wangchuck Public Affairs Bhutan Dhondo Keshav Karve Literature & Education Maharashtra 1955 J. R. D. Tata Trade & Industry Maharashtra Fazal Ali Public Affairs Bihar 1956 Jankibai Bajaj Social Work Madhya Pradesh Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi Public Affairs Madhya Pradesh Ghanshyam Das Birla Trade & Industry Rajashtan 1957 Sri Prakasa Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh M. C. Setalvad Public Affairs Maharashtra John Mathai Literature & Education Kerala 1959 Gaganvihari Lallubhai Mehta Social Work Maharashtra Radhabinod Pal Public Affairs West Bengal 1960 Naryana Raghvan Pillai Public Affairs Tamil Nadu H. V. R. Iyengar Civil Service Tamil Nadu 1962 Padmaja Naidu Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit Civil Service Uttar Pradesh A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar Medicine Tamil Nadu 1963 Hari Vinayak Pataskar Public Affairs Maharashtra Suniti Kumar Chatterji Literature