FDA Oral History, Wilkens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liquid Lunch

Liquid Lunch Easy-Intermediate Clogging Line Dance Choreographer: Karen Tripp Music by Caro Emerald (album: The Shocking Miss Emerald), 113 bpm [email protected] Begin with left foot. Dashes in description indicate separate beats. RF indicates right foot lead. INTRO: Wait 8 beats (4) – 1 Brush & Turn 1/4 L DS-BrSl(1/4 L)-DS-RS (4) 4 – 2 Single Touches / Touch Up DS-TchSl PART A: repeats with opposite foot (8) – 1 Clogover Slur Vine DS(s)-DS(xf)-DS(s)-SlurS(xb)-DS(s)-DS(xf)-DS-RS (4) 2 1 Flatland RF Dt(bk)Sl-BrSl-DS-RS (4) – 1 Triple DS-DS-DS-RS PART B: (8) 1 Turning Cowboy DS-DS-DS-BrSl(1/4 L)-DS(1/4 L)-RS-RS-RS; to face back forward on beats 1–3 and back on beats 6–8 (8) 2 Brush Donkeys DS-BrSl-Tch(xf)Sl-Tch(f)Sl (8) 1 Turning Cowboy to face front (4) 2 Basics DS-RS (4) 1 Over the Log (p)St(f)-(p)St(f)-St(bk)St(bk)-(p)Clap PART C1: repeats with same foot facing back (4) – 1 Rooster Run DS(s)-DS(xf)-To(s)To(xb)-To(s)St(xf); move L (4) 1 Push-off / Side Rocks DS-RS-RS-RS; move L (4) 2 1 Turning Rocks / Turning Push-off 1/2 R DS-RS-RS-RS; turn 1/2 R (4) – 1 Double Rock 2 / Fancy Double DS-DS-RS-RS BRIDGE: (8) 1 8-Cnt Roundout / Cross Toe Heels DS-ToHw(xf)-ToHw(bk)-ToHw(s)-ToHw(xf)-ToHw(bk)-ToHw(s)- ToHw(s) ABBREVIATIONS Repeat A: [Clogover Slur Vine, Flatland, Triple, repeat all] D, Dt = DoubleToe Repeat B: [Turning Cowboy, Brush Donkeys, Turning Cowboy, Basics, Over the Log] S, St = Step Repeat C1: [Rooster Run, Push-off, Turning Rocks, Double Rock 2, repeat all] DS = Dt-Step Repeat Bridge: [8-Cnt Roundout] Br = Brush BREAK: repeats with -

Karaoke-Katalog Update Vom: 17/06/2020 Singen Sie Online Auf Gesamter Katalog

Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 17/06/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Dance Monkey - Tones and I Rote Lippen soll man küssen - Gus Backus Amoi seg' ma uns wieder - Andreas Gabalier Perfect - Ed Sheeran Tears In Heaven - Eric Clapton Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens My Way - Frank Sinatra You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Angels - Robbie Williams 99 Luftballons - Nena Up Where We Belong - Joe Cocker Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Zombie - The Cranberries All of Me - John Legend Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch New York, New York - Frank Sinatra Blinding Lights - The Weeknd Niemals In New York Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Creep - Radiohead EXPLICIT Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Let It Be - The Beatles Always Remember Us This Way - A Star is Born Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer A Million Dreams - The Greatest Showman Kuliko Jana, Eine neue Zeit - Oonagh Eine Nacht - Ramon Roselly In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley (Everything I Do) I Do It For You - Bryan Adams Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Egal - Michael Wendler Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Der hellste Stern (Böhmischer Traum) - DJ Ötzi Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Uber den Wolken - Reinhard Mey Losing My Religion - R.E.M. -

Caro Emerald

Cruise-lovers are in for a treat this New Year's Eve as P&O Cruises are set to host a spectacular live BBC Radio 2 outside broadcast in Madeira aboard Oceana with a performance from Dutch jazz singer Caro Emerald. The artist will be playing two CARO EMERALD sets of her best-loved songs in a first-ever live BBC performance on board a P&O Cruises ship. Caro Emerald will be introduced by presenter Ana Matronic who will be broadcasting live on Radio 2 from 11 pm. Caro Emerald has fashioned her own niche of retro jazz with sampling and modern pop since the release of her multi-platinum debut album, Deleted Scenes from the Cutting Floor, in 2010, while Matronic is best known as the lead singer of Scissor Sisters, whose hits include I Don't Feel like Dancin' and 'Take Your Mama'. - burtonmail.co.uk In August 2010, Caro Emerald's debut album, Deleted Scenes from the Cutting Room Floor, spent its 30th week at #1 in the Dutch album charts, setting an all-time record and beating Michael Jackson's "Thriller" by one week. The album became the biggest selling album of 2010 in the Netherlands with over 350.000 copies to date. Worldwide, over 1.4 million copies have been sold. On October 3, 2010, Emerald was awarded the Dutch music prize "Edison Award" for Best Female Artist. In May 2013, Caro's second album, The Shocking Miss Emerald, was released. It entered at #1 in the UK album chart. + + + + + Thanks to UncleBoko for sharing the show at Dime. -

1 Marvin Gaye What's Going on 2 Otis Redding

1 Marvin Gaye What's going on 2 Otis Redding (Sittin' on) The dock of the bay 3 Amy Winehouse Back to black 4 Marvin Gaye Let's get it on 5 Kyteman Sorry 6 Bill Withers Ain't no sunshine 7 Stevie Wonder Superstition 8 John Legend All of me 9 Aretha Franklin Respect 10 Miles Davis So what 11 Sam Cooke A change is gonna come 12 Curtis Mayfield Move on up 13 Al Green Let's stay together 14 James Brown It's a man's man's man's world 15 Michael Jackson Billie Jean 16 Gregory Porter Be good (lion's song) 17 Temptations Papa was a rollin' stone 18 Beyonce ft. Jay-Z Crazy in love 19 Dave Brubeck Take five 20 Earth Wind & Fire September 21 Erykah Badu Tyrone (live) 22 Gregory Porter 1960 what 23 Stevie Wonder As 24 Daft Punk ft. Pharrell & Nile RodgersGet lucky 25 Gladys Knight & The Pips Midnight train to Georgia 26 James Brown Sex machine 27 Michael Kiwanuka Home again 28 Michael Jackson Don't stop 'till you get enough 29 B.B. King The thrill is gone 30 Luther Vandross Never too much 31 Stevie Wonder Sir Duke 32 Michael Jackson Off the wall 33 Donny Hathaway A song for you 34 Bobby Womack Across 110th street 35 Earth Wind & Fire Fantasy 36 Bill Withers Grandma's hands 37 Roots ft. Cody Chesnutt The seed (2.0) 38 Billy Paul Me and mrs Jones 39 Marvin Gaye I heard it through the grapevine 40 Etta James At last 41 Chaka Khan I'm every woman 42 Bill Withers Lovely day 43 Giovanca How does it feel 44 Isaac Hayes Theme from Shaft 45 Alicia Keys Empire state of mind (part 2) 46 Chic Le freak 47 Dusty Springfield Son of a preacher man 48 Pharrell Happy -

BUT WILL IT PLAY in GRAND RAPIDS? the ROLE of GATEKEEPERS in MUSIC SELECTION in 1960S TOP 40 RADIO

BUT WILL IT PLAY IN GRAND RAPIDS? THE ROLE OF GATEKEEPERS IN MUSIC SELECTION IN 1960s TOP 40 RADIO By Leonard A. O’Kelly A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Media and Information Studies - Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT BUT WILL IT PLAY IN GRAND RAPIDS? THE ROLE OF GATEKEEPERS IN MUSIC SELECTION IN 1960s TOP 40 RADIO By Leonard A. O’Kelly The decision to play (or not to play) certain songs on the radio can have financial ramifications for performers and for radio stations alike in the form of ratings and revenue. This study considers the theory of gatekeeping at the individual level, paired with industry factors such as advertising, music industry promotion, and payola to explain how radio stations determined which songs to play. An analysis of playlists from large-market Top 40 radio stations and small-market stations within the larger stations’ coverage areas from the 1960s will determine the direction of spread of song titles and the time frame for the spread of music, shedding light on how radio program directors (gatekeepers) may have been influenced in their decisions. By comparing this data with national charts, it may also be possible to determine whether or not local stations had any influence over the national trend. The role of industry trade publications such as Billboard and The Gavin Report are considered, and the rise of the broadcast consultant as a gatekeeper is explored. This study will also analyze the discrepancy in song selection with respect to race and gender as compared to national measures of popularity. -

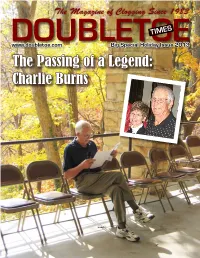

Charlie Burns

The Magazine of Clogging Since 1983 TIMES DOUBLETOEwww.doubletoe.com Big Special Holiday Issue 2013 The Passing of a Legend: Charlie Burns DOUBLETOE July/Augustfoot 2010print CloggingNovember/December Group Trips 2013 In This Issue Lee Froehle has been coordinating clogging trips and OnIndex Dancer... .........................................................................................2 tours for more than a decade and has taken her own Editorial “Changing Channels” ...........................................4 groups to Europe, DisneyIn and This around the IssueU.S. She Calendar Even Santa of Events has a ................................................................... reindeer that pays homage 6 has also organized Clogging Expos for over 1,000 toVirginia the hobby Clogger we Dorothylove. Thanks Stephenson to the ........................ vast 8 Index .........................................................................................people in Washington, DC, plus Hawaii. Ireland, 2 resourcesCherryholmes of the Interview internet, ................................................ I found this story about14 EditorialScotland “On and Dancer” more. ........................................................ Whether you are a small group 2 theDancers reindeer in Action “Dancer.” Photo Contest ..............................23 A Clogger’swanting Nighta fun trip, Before a cruise Christmas for a few ..........................families or a 4 Choreography Dancer is one “Get of theBack” more laid back reindeer of Calendarlarge studioof Events -

Alex Garland

The Beach — Alex Garland The Beach Alex Garland Boom-Boom Vietnam, me love you long time. All day, all night, me love you long time. "Delta One-Niner, this is Alpha patrol. We are on the north-east face of hill Seven-Zero- Five and taking fire, I repeat, taking fire. Immediate air assistance required on the fucking double. Can you confirm?" Radio static. "I say again, this is Alpha patrol and we are taking fire. Immediate air assistance required. Can you confirm? We are taking fire. Please confirm. We are… Incoming, incoming!" Boom. "… Medic!" Dropping acid on the Mekong Delta, smoking grass through a rifle barrel, flying on a helicopter with opera blasting out of loudspeakers, tracer-fire and paddy-field scenery, the file:///C|/Users/User/Desktop/PdfBook/FILMAN~1/THEBEA~1.HTM[2015-09-01 오후 1:24:59] The Beach — Alex Garland smell of napalm in the morning. Long time. Yea, though I walk through the valley of death I will fear no evil, for my name is Richard. I was born in 1974. BANGKOK Bitch The first I heard of the beach was in Bangkok, on the Khao San Road. Khao San Road was backpacker land. Almost all the buildings had been converted into guest-houses, there were long-distance-telephone booths with air-con, the cafés showed brand-new Hollywood films on video, and you couldn't walk ten feet without passing a bootleg-tape stall. The main function of the street was as a decompression chamber for those about to leave or enter Thailand, a halfway house between East and West. -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 5-23-1940 The aC rroll News- Vol. 20, No. 16 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 20, No. 16" (1940). The Carroll News. 378. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/378 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Edited For and By the Students of John Carroll University ZSS7-A VoL XX CLEVELAND, OHIO, MAY 23, 1940 No. 16 94 S·en iors Receive Diplomas on June 6 ~--------------------------------------- Class of '41 Elect:s McCart:hy Rev. A.J. Hogan Joyce Elecl:ed Pres_idenl: President After Tie Vote . Guest Spea~er Of Union Execul:ive Cou.ncil McCarthy, Marcus, Trudel, and Myers Head Next Year's At Graduatton Junior From Y oungsto wn Gains Top Post in Student Seniors as Union Rules on Disputed Ballot The 1940 .Commencement ex- Governing B ody by Wide Margin; Ennen Elected Vice-Presiden t Following a tie vote in the regularly scheduled junior class elec ercises will see a class largest in As the Carroll Union Executive Council for 1940-1941 met for tion, Joseph McCarthy of Cleveland won the presidency of next year's the history of John Carroll Univer- the first time, on May 16, William Joyce of Youngstown, Ohio, was • senior class in a run-off election. -

Catalogue Karaoké Mis À Jour Le: 29/07/2021 Chantez En Ligne Sur Catalogue Entier

Catalogue Karaoké Mis à jour le: 29/07/2021 Chantez en ligne sur www.karafun.fr Catalogue entier TOP 50 J'irai où tu iras - Céline Dion Femme Like U - K. Maro La java de Broadway - Michel Sardou Sous le vent - Garou Je te donne - Jean-Jacques Goldman Avant toi - Slimane Les lacs du Connemara - Michel Sardou Les Champs-Élysées - Joe Dassin La grenade - Clara Luciani Les démons de minuit - Images L'aventurier - Indochine Il jouait du piano debout - France Gall Shallow - A Star is Born Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen La bohème - Charles Aznavour A nos souvenirs - Trois Cafés Gourmands Mistral gagnant - Renaud L'envie - Johnny Hallyday Confessions nocturnes - Diam's EXPLICIT Beau-papa - Vianney La boulette (génération nan nan) - Diam's EXPLICIT On va s'aimer - Gilbert Montagné Place des grands hommes - Patrick Bruel Alexandrie Alexandra - Claude François Libérée, délivrée - Frozen Je l'aime à mourir - Francis Cabrel La corrida - Francis Cabrel Pour que tu m'aimes encore - Céline Dion Les sunlights des tropiques - Gilbert Montagné Le reste - Clara Luciani Je te promets - Johnny Hallyday Sensualité - Axelle Red Anissa - Wejdene Manhattan-Kaboul - Renaud Hakuna Matata (Version française) - The Lion King Les yeux de la mama - Kendji Girac La tribu de Dana - Manau (1994 film) Partenaire Particulier - Partenaire Particulier Allumer le feu - Johnny Hallyday Ce rêve bleu - Aladdin (1992 film) Wannabe - Spice Girls Ma philosophie - Amel Bent L'envie d'aimer - Les Dix Commandements Barbie Girl - Aqua Vivo per lei - Andrea Bocelli Tu m'oublieras - Larusso -

LIKE MEN DO: STORIES by Anthony D.E

© COPYRIGHT by Anthony D.E. Wilson 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DEDICATION To David, Jack, Lisa and Walter. LIKE MEN DO: STORIES BY Anthony D.E. Wilson ABSTRACT This collection examines the often-hidden emotions of men, the frequently tenu- ous relationship between fathers and sons, and the way men act when they aren’t the way society wants them to be. Brothers, both adopted, face the prospect of being fathers themselves; a lonely man finds connection through violence; a best friend wonders how far he can go to repay his indebtedness; a giant seeks to find what makes him feel small; a father considers the gravity of his betrayal as he looks back on the mistakes of his own dad; and a man looks back on a night decades earlier that exemplified the helplessness he feels. Amidst all of these stories are narratives about how men live in a world of expecta- tions, where acknowledging the depth of their souls often is seen as a weakness instead of strength. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank all the men in my life who inspired these stories, whether through their presence or their absence. I owe a debt of gratitude to all the professors who have helped me recognize what’s good and what’s not, including Denise Orenstein, E.J. Levy, Andrew Holleran, Richard McCann and David Keplinger. Also, a hat tip is due to all the other students in American University’s graduate creative writing program, who daily provide inspiration and welcome criticism. I want to thank my thesis committee, Glenn Moomau and Rachel Louise Snyder, whose comments pushed this piece further than I thought it could go. -

Amund Storsveen July 2013 Issue 207 • £3.50 SINGIN’ & DANCIN’ in the RAIN!

The monthly magazine dedicated to Line dancing Amund Storsveen July 2013 Issue 207 • £3.50 SINGIN’ & DANCIN’ IN THE RAIN! PULL-OUT INSIDE • 14 GREAT DANCE SCRIPTS INCLUDING : DAME DE ESO • WISH FOR YOU • LIQUID LUNCH • MY FIRST LOVE cover207.indd 1 28/06/2013 08:59 1120291 1120291 HH.indd 1 28/06/2013 09:00 July 2013 What makes a dance great for you? Music? Steps? The perfect combination of both? The name of the script’s author? Is that name one of your main considerations to try out something new? Does a Maggie or Robbie dance make the grade for you because you know it is going to be fantastic? I am always amazed at the tidal wave of stepsheets that reach our office week in, week out. I am also stunned when I see how many of those come from relative unknowns. Sometimes, I get to think that writing a dance in Line dance terms and hoping to see it “make it” is a very real stroke of luck. I know that those hundreds of weekly dances are not all gold but I also know that a good proportion of them deserve a better chance than what they do get. Kath, our dance editor, has a hard task each month because we agreed, years ago now, to make sure we offer a good selection of new names and more established choreographers, each month. Her research is always extensive as she tries hard to give a lot of new people a break. However, the truth remains that to get a hit in terms of Line dance is not easy. -

Read an Excerpt

Waiter to the Rich and Shameless Confessions of a Five-Star Beverly Hills Server By Paul Hartford Copyright © 2014 Paul Hartford All rights reserved. DEDICATION To all hospitality workers, whether you’re serving the Rich and Shameless or the poor and blameless, and to all corporate grunts plugging away in a 9 to 5 world, dreaming about getting out but not yet having the courage to actually do it. And to my wonderful wife who stood by my side and worked so hard with me on this book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE PROLOGUE CHAPTER 1: ALMOST FAMOUS CHAPTER 2: MODERN TIMES CHAPTER 3: COCKTAIL CHAPTER 4: THE PARTY CHAPTER 5: THE WAY WE WERE CHAPTER 6: TRAINING DAY CHAPTER 7: A STAR IS BORN CHAPTER 8: THE LIVES OF OTHERS CHAPTER 9: RUTHLESS PEOPLE CHAPTER 10: THE MAN WHO WOULD BE KING CHAPTER 11: HOW TO SUCCEED IN BUSINESS WITHOUT REALLY TRYING CHAPTER 12: THE HANGOVER CHAPTER 13: SUNSET BOULEVARD CHAPTER 14: IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE CHAPTER 15: ORDINARY PEOPLE CHAPTER 16: UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN CHAPTER 17: ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST CHAPTER 18: TITANIC CHAPTER 19: WHAT DREAMS MAY COME EPILOGUE Preface The events in this story are all true and celebrities’ names have not been altered. According to my lawyer I didn’t need to do so. However, the names of my co-workers have been changed to protect the innocent and the guilty. And, the name of the establishment has been altered – mostly to protect myself from their powerful hand – at the request of my attorney whose job it is to protect me from lawsuits.