Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release Wolfgang Rihm Is the LUCERNE

Media Release Wolfgang Rihm Is the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY’s New Artistic Director Matthias Pintscher Named Principal Conductor Lucerne, 04 September 2015 . Starting in the summer of 2016, the German composer Wolfgang Rihm will assume overall artistic directorship of the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY. The conductor and composer Matthias Pintscher will support him as Principal Conductor and will be responsible each summer for a central Academy program; he will additionally focus on developing the Academy Orchestra. Both contracts are for a period of five years. The founder of the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY, Pierre Boulez, will continue to remain in close dialogue with Wolfgang Rihm, Matthias Pintscher, and the Festival team as Honorary President of the Academy. For twelve years the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY has been regarded as a unique international educational campus in the field of contemporary classical music of the 20th and 21st centuries. It offers continuing training not only for some 120 instrumentalists between 18 and 32 years of age but also for young directors and composers. “I am extremely delighted that in the person of Wolfgang Rihm a leading figure of contemporary music will be taking over artistic leadership of the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY,” remarks Michael Haefliger, LUCERNE FESTIVAL’s Executive and Artistic Director. “On the strength of his experience and his knowledge in connection with the Academy, Wolfgang Rihm will be in a position to establish new directions for linking creativity with effective ways of working together for young instrumentalists, conductors, and composers. This summer Matthias Pintscher has returned for a third time as a teacher and conductor to help shape the Academy’s work in marvelous ways, as seen for example in the recent “Day for Pierre Boulez”. -

Klsp2018iema Broschuere.Indd

KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY IN TIROL. REBECCA SAUNDERS COMPOSER IN RESIDENCE. 15TH EDITION 29.08. – 09.09.2018 KLANGSPUREN INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY 2018 KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ is celebrating its 25th anniversary in 2018. The annual Tyrolean festival of contemporary music provides a stage for performances, encounters, and for the exploration and exchange of new musical ideas. With a different thematic focus each year, KLANGSPUREN aims to present a survey of the fascinating, diverse panorama that the music of our time boasts. KLANGSPUREN values open discourse, participation, and partnership and actively seeks encounters with locals as well as visitors from abroad. The entire beautiful region of Tyrol unfolds as the festival’s playground, where the most cutting-edge and modern forms of music as well as many young composers and musicians are presented. On the occasion of its own milestone anniversary – among other anniversaries that KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ 2018 will be celebrating this year – the 25th edition of the festival has chosen the motto „Festivities. Places.“ (in German: „Feste. Orte.“). The program emphasizes projects and works that focus on aspects of celebrations, festivities, rituals, and events and have a specific reference to place and situation. KLANGSPUREN INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY is celebrating its 15th anniversary. The Academy is an offshoot of the renowned International Ensemble Modern Academy (IEMA) in Frankfurt and was founded in the same year as IEMA, in 2003. The Academy is central to KLANGSPUREN and has developed into one of the most successful projects of the Tyrolean festival for new music. The high standards of the Academy are vouched for by prominent figures who have acted as Composers in Residence: György Kurtág, Helmut Lachenmann, Steve Reich, Benedict Mason, Michael Gielen, Wolfgang Rihm, Martin Matalon, Johannes Maria Staud, Heinz Holliger, George Benjamin, Unsuk Chin, Hans Zender, Hans Abrahamsen, Wolfgang Mitterer, Beat Furrer, Enno Poppe, and most recently in 2017, Sofia Gubaidulina. -

With a Rich History Steeped in Tradition, the Courage to Stand Apart and An

With a rich history steeped in tradition, the courage to stand apart and an enduring joy of discovery, the Wiener Symphoniker are the beating heart of the metropolis of classical music, Vienna. For 120 years, the orchestra has shaped the special sound of its native city, forging a link between past, present and future like no other. In Andrés Orozco-Estrada - for several years now an adopted Viennese - the orchestra has found a Chief Conductor to lead this skilful ensemble forward from the 20-21 season onward, and at the same time revisit its musical roots. That the Wiener Symphoniker were formed in 1900 of all years is no coincidence. The fresh wind of Viennese Modernism swirled around this new orchestra, which confronted the challenges of the 20th century with confidence and vision. This initially included the assured command of the city's musical past: they were the first orchestra to present all of Beethoven's symphonies in the Austrian capital as one cycle. The humanist and forward-looking legacy of Beethoven and Viennese Romanticism seems tailor-made for the Symphoniker, who are justly leaders in this repertoire to this day. That pioneering spirit, however, is also evident in the fact that within a very short time the Wiener Symphoniker rose to become one of the most important European orchestras for the premiering of new works. They have given the world premieres of many milestones of music history, such as Anton Bruckner's Ninth Symphony, Arnold Schönberg's Gurre-Lieder, Maurice Ravel's Piano Concerto for the Left Hand and Franz Schmidt's The Book of the Seven Seals - concerts that opened a door onto completely new worlds of sound and made these accessible to the greater masses. -

AMERICAN ACADEMY in ROME PRESENTS the SCHAROUN ENSEMBLE CONCERT SERIES 14-16 JANUARY 2011 at VILLA AURELIA Exclusive Concert

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 11, 2011 AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME PRESENTS THE SCHAROUN ENSEMBLE CONCERT SERIES 14-16 JANUARY 2011 AT VILLA AURELIA Exclusive Concert Dates in Italy for the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin Courtesy of the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin Rome – The American Academy in Rome is pleased to present a series of three concerts by one of Germany’s most distinguished chamber music ensembles, the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin. Comprised of members of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin specializes in a repertoire of Classical, Romantic, 20th century Modernist, and contemporary music. 2011 marks the third year of collaboration between the Ensemble and the American Academy in Rome, which includes performances of work by current Academy Fellows in Musical Composition Huck Hodge and Paul Rudy, as well as 2009 Academy Fellow Keeril Makan. Featuring soprano Rinnat Moriah, the Ensemble will also perform music by Ludwig van Beethoven, John Dowland, Antonin Dvořák, Sofia Gubaidulina, Heinz Holliger, Luca Mosca, and Stefan Wolpe. The concerts are free to the public and will take place at the Academy’s Villa Aurelia from 14-16 January 2011. Event: Scharoun Ensemble Berlin (preliminary program*) 14 January at 9pm – Ludwig van Beethoven, John Dowland, Huck Hodge, and Stefan Wolpe 15 January at 9pm – Sofia Gubaidulina, Huck Hodge, Heinz Holliger and Keeril Makan 16 January at 11am – Antonin Dvořák, Luca Mosca, and Paul Rudy *subject to change Location: Villa Aurelia, American Academy in Rome Largo di Porta San Pancrazio, 1 Scharoun Ensemble Berlin The Scharoun Ensemble Berlin was founded in 1983 by members of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. -

A Perspective of New Simplicity in Contemporary Composition: Song of Songs As a Case Study Isabel Maria Pereira Barata Da Rocha

MESTRADO COMPOSIÇÃO E TEORIA MUSICAL A perspective of New Simplicity in contemporary composition: Song of Songs as a case study Isabel Maria Pereira Barata da Rocha 06/2017 A perspective of New Simplicity in contemporary composition: Song of Songs as a case study. Isabel Maria Pereira Barata da Rocha MESTRADO M COMPOSIÇÃO E TEORIA MUSICAL A perspective of New Simplicity in contemporary composition: Song of Songs as a case study Isabel Maria Pereira Barata da Rocha Dissertação apresentada à Escola Superior de Música e Artes do Espetáculo como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Composição e Teoria Musical Professor Orientador Professor Doutor Eugénio Amorim Professora Coorientadora Professora Doutora Daniela Coimbra 06/2017 A perspective of New Simplicity in contemporary composition: Song of Songs as a case study. Isabel Maria Pereira Barata da Rocha Dedico este trabalho a todos os homens e todas as mulheres de boa vontade. A perspective of New Simplicity in contemporary composition: Song of Songs as a case study. Isabel Maria Pereira Barata da Rocha A perspective of New Simplicity in contemporary composition: Song of Songs as a case study. Isabel Maria Pereira Barata da Rocha Agradecimentos À minha filha Luz, que me dá a felicidade de ser sua mãe, pelo incentivo. Aos meus pais Ana e Luís, pelo apoio incondicional. A Ermelinda de Jesus, pela ajuda sempre disponível. À Fátima, à Joana e à Mariana, pela amizade profunda. Ao José Bernardo e aos avós Teresa e António José, pelo auxílio. Ao Pedro Fesch, pela compreensão e pela aposta na formação dos professores em quem confia. -

Scharoun Ensemble Berlin

SCHAROUN ENSEMBLE BERLIN Founded in 1983 by members of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the Scharoun Ensemble is one of Germany’s leading chamber-music organizations. With its wide repertoire, ranging from composers of the Baroque period by way of Classical and Romantic chamber music to contemporary works, the Scharoun Ensemble has been inspiring audiences in Europe and overseas for more than a quarter of a century. Innovative programming, a refined tonal culture and spirited interpretations are hallmarks of the ensemble, which performs in a variety of instrumental combinations. The permanent core of the Scharoun Ensemble is a classical octet (clarinet, bassoon, horn, two violins, viola, cello and double bass), apart from Wolfram Brandl and Claudio Bohorquez they are made up entirely of members of the Berlin Philharmonic. When called for, the ensemble brings in additional instrumentalists as well as noted conductors. The Scharoun Ensemble has prepared and presented various programmes under the direction of Claudio Abbado, Sir Simon Rattle, Daniel Barenboim and Pierre Boulez. It has also performed with singers including Thomas Quasthoff, Simon Keenlyside and Barbara Hannigan, and, for interdisciplinary projects, the ensemble has engaged such artists as Fanny Ardant, Loriot and Dominique Horwitz. Bridging the gap between tradition and the modern is the Scharoun Ensemble’s principal artistic focus. It has given world premieres of many 20th- and 21st-century compositions while dedicating itself with equal passion to the interpretation of works from past centuries. Among the cornerstones of its repertoire are Franz Schubert’s Octet d803, with which the ensemble made its public debut in 1983, and Ludwig van Beethoven’s Septet Op.20. -

Digital Concert Hall Where We Play Just for You

www.digital-concert-hall.com DIGITAL CONCERT HALL WHERE WE PLAY JUST FOR YOU PROGRAMME 2016/2017 Streaming Partner TRUE-TO-LIFE SOUND THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL AND INTERNET INITIATIVE JAPAN In the Digital Concert Hall, fast online access is com- Internet Initiative Japan Inc. is one of the world’s lea- bined with uncompromisingly high quality. Together ding service providers of high-resolution data stream- with its new streaming partner, Internet Initiative Japan ing. With its expertise and its excellent network Inc., these standards will also be maintained in the infrastructure, the company is an ideal partner to pro- future. The first joint project is a high-resolution audio vide online audiences with the best possible access platform which will allow music from the Berliner Phil- to the music of the Berliner Philharmoniker. harmoniker Recordings label to be played in studio quality in the Digital Concert Hall: as vivid and authen- www.digital-concert-hall.com tic as in real life. www.iij.ad.jp/en PROGRAMME 2016/2017 1 WELCOME TO THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL In the Digital Concert Hall, you always have Another highlight is a guest appearance the best seat in the house: seven days a by Kirill Petrenko, chief conductor designate week, twenty-four hours a day. Our archive of the Berliner Philharmoniker, with Mozart’s holds over 1,000 works from all musical eras “Haffner” Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s for you to watch – from five decades of con- “Pathétique”. Opera fans are also catered for certs, from the Karajan era to today. when Simon Rattle presents concert perfor- mances of Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre and The live broadcasts of the 2016/2017 Puccini’s Tosca. -

Tonalitysince 1950

Tonality Since 1950 Tonality Since 1950 documents the debate surrounding one of the most basic technical and artistic resources of music in the later 20th century. The obvious flourishing of tonality – a return to key, pitch center, and consonance – in recent decades has undermi- ned received views of its disintegration or collapse ca. 1910, in- tensifying the discussion of music’s acoustical-theoretical bases, and of its broader cultural and metaphysical meanings. While historians of 20th-century music have often marginalized tonal practices, the present volume offers a new emphasis on emergent historical continuities. Musicians as diverse as Hindemith, the Beatles, Reich, and Saariaho have approached tonality from many different angles: as a figure of nostalgic longing, or as a universal law; as a quoted artefact of music’s sedimented stylistic past, or as a timeless harmonic resource. Essays by 15 leading contributors cover a wide repertoire of concert and pop/rock music composed Tonal in Europe and America over the past half-century. Tonality Since 1950 Since 1950 ISBN 978-3-515-11582-7 www.steiner-verlag.de Musikwissenschaft Franz Steiner Verlag Franz Steiner Verlag Edited by Felix Wörner, TonaWörner / Scheideler/ Rupprecht liUllricht Scheideler and Philipy Rupprecht Tonality Since 1950 Edited by Felix Wörner, Ullrich Scheideler and Philip Rupprecht Tonality Since 1950 Edited by Felix Wörner, Ullrich Scheideler and Philip Rupprecht Franz Steiner Verlag Mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.d-nb.de> abrufbar. Dieses Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. -

Zeitgenössische Musik

Montag, 9. bis Freitag, 13. Februar 2015 AKADEMIE FÜR ZEITGENÖSSISCHE MUSIK Internationale Masterclasses Luzern Flöte | Saxofon | Klarinette | Trompete | Gitarre | Violine | Violoncello | Kontrabass | Klavier | Akkordeon | Gesang | Schlagzeug | Harfe | Kammermusik | Komposition | Improvisation 2 Im Mittelpunkt des Kurses steht eine intensive Auseinandersetzung mit dem Repertoire des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts. Neben der Zusammenarbeit mit dem Composer-in-Residence Wolfgang Rihm finden diverse Workshops und Seminare zu den Themen Aufführung, Geschichte und Analyse der Neuen Musik statt. Die Dozierenden sind Mitglieder der europaweit führenden Ensembles für Neue Musik sowie international gefragte Solistinnen und Pädagogen. Sie werden im Unterricht sowie in Form von Vorträgen Fragen thematisieren, die für Verständnis und Ausführung von zeitgenössischer Musik entscheidend sind. 3 Dozierende David Alberman, Dieter Ammann, Sascha Armbruster, Anne Bassand, Marco Blaauw, Erik Borgir, Andreas Brenner, Uli Fussenegger, Pirmin Grehl, Florian Hoelscher, Anne-Maria Hölscher, Angelika Luz, Urban Mäder, Heinrich Mätzener, Ulrich Mosch, Pascal Pons, Wolfgang Rihm, Mats Scheidegger Kursprogramm Montag, 09. Februar 2014 09.00 Uhr Einschreibung 10.00 bis 12.45 Uhr Instrumentalunterricht | Seminare 14.00 bis 17.30 Uhr Kammermusik | Workshops 19.00 Uhr Dozierendenkonzert Dienstag, 10. bis Freitag, 13. Februar 2015 09.15 bis 12.45 Uhr Instrumentalunterricht | Seminare 14.00 bis 17.30 Uhr Kammermusik | Workshops 19.00 bis 21.00 Uhr Abendveranstaltungen Workshops -

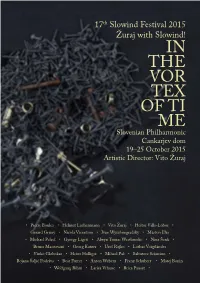

In the Vor Tex of Ti Me

17th Slowind Festival 2015 Žuraj with Slowind! IN THE VOR TEX OF TI Slovenian PhilharmonicME Cankarjev dom 19–25 October 2015 Artistic Director: Vito Žuraj • Pierre Boulez • Helmut Lachenmann • Vito Žuraj • Heitor Villa-Lobos • Gérard Grisey • Nicola Vicentino • Ivan Wyschnegradsky • Márton Illés • Michael Pelzel • György Ligeti • Alwyn Tomas Westbrooke • Nina Šenk • Bruno Mantovani • Georg Katzer • Uroš Rojko • Lothar Voigtländer • Vinko Globokar • Heinz Holliger • Mihael Paš • Salvatore Sciarrino • Bojana Šaljić Podešva • Beat Furrer • Anton Webern • Franz Schubert • Matej Bonin • Wolfgang Rihm • Larisa Vrhunc • Brice Pauset • Valued Listeners, It is no coincidence that we in Slowind decided almost three years ago to entrust the artistic direction of our festival to the penetrating, successful and (still) young composer Vito Žuraj. And it is precisely in the last three years that Vito has achieved even greater success, recently being capped off with the prestigious Prešeren Fund Prize in 2014, as well as a series of performances of his compositions at a diverse range of international music venues. Vito’s close collaboration with composers and performers of various stylistic orientations was an additional impetus for us to prepare the Slowind Festival under the leadership of a Slovenian artistic director for the first time! This autumn, we will put ourselves at the mercy of the vortex of time and again celebrate to some extent. On this occasion, we will mark the th th 90 birthday of Pierre Boulez as well as the 80 birthday of Helmut Lachenmann and Georg Katzer. In addition to works by these distinguished th composers, the 17 Slowind Festival will also present a range of prominent composers of our time, including Bruno Mantovani, Brice Pauset, Michael Pelzel, Heinz Holliger, Beat Furrer and Márton Illés, as well as Slovenian composers Larisa Vrhunc, Nina Šenk, Bojana Šaljić Podešva, Uroš Rojko, and Matej Bonin, and, of course, the festival’s artistic director Vito Žuraj. -

Sperrfrist 27

räsonanz Press Release March 2017 räsonanz – donor Concerts 2017 for the First Time in Munich and Lucerne MusicAeterna Choir from Perm hosted for the First Time in Munich | Swiss Premiere of Rihm’s Requiem-Strophen As part of an initiative by the EvS Music Foundation the Mahler Chamber Orchestra as well as the MusicAeterna Choir will be coming to Munich in 2017 to perform under the baton of Teodor Currentzis. This will be the famous Perm-based choir’s debut performance in the regional capital. The concert will be organized by Bayerischer Rundfunk’s musica viva. The symphony orchestra along with the choir of Bavaria’s regional broadcaster Bayerischer Rundfunk will be hosted in Lucerne under the baton of Mariss Jansons to perform the Swiss debut of Wolfgang Rihm’s Requiem-Strophen – the presenter is LUCERNE FESTIVAL. After the successful launch of the concert series räsonanz – donor concert 2016 in Munich the initiative is now to be extended from 2017 to include a concert in Lucerne. Next year it is also planned for Munich and Lucerne to host one concert each. “As a member of the Board of Trustees Pierre Boulez himself expressed the wish almost 20 years ago for the foundation to become more actively involved in the contemporary music scene and to launch its own initiatives. With räsonanz the foundation is sure to have reached its highest point until now through its focus on major composers,” explains Michael Roßnagl, Managing Director at the EvS Music Foundation. The aim of the initiative is to enable contemporary works with large line-ups to be performed by top international orchestras in Munich and Lucerne. -

Wolfgang RIHM

Wolfgang RIHM Lichtzwang (In memoriam Paul Celan) Dritte Musik Gedicht des Malers • Tianwa Yang, Violin Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz Christoph-Mathias Mueller Wolfgang Rihm (b. 1952) Lichtzwang (In memoriam Paul Celan) • Dritte Musik • Gedicht des Malers Wolfgang Rihm was born in Karlsruhe on 13 March 1952. compositional career as well as providing an overview of Written in 1993 and first performed in Baden Baden on Written during 2012–14 and premiered in Vienna on He began composing at the age of 11 – studying with his varied stylistic thinking. Contemporary without being 7 May 1993 by Gottfried Schneider with the South West 9 January 2015 by Renaud Capuçon (also the dedicatee) Eugen Werner Velte at the Staatliche Hochschule für self-consciously ‘modern’, while making relatively German Radio Symphony Orchestra and Michael Gielen, with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra and Philippe Musik in Karlsruhe during 1968–72, with Karlheinz infrequent recourse to the novel or unorthodox playing Dritte Musik is (as the title implies) Rihm’s third concertante Jordan, Gedicht des Malers (‘Poem of the Painter’) was Stockhausen in Cologne during 1972–73 as well as with techniques favoured by many of his contemporaries, these work for violin and orchestra, but it is also a revision and inspired by an imagined image of the German artist Max the late Klaus Huber at Freiburg’s Staatliche Hochschule works are free in their evolution while lacking nothing in expansion of Dunkles Spiel (1989–90) for chamber Beckmann (1884–1950) portraying the Belgian violinist für Musik during 1973–76. He received an honorary formal logic or expressive consistency – thereby making orchestra.