From Sea to Sea (To Sea) to

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizenship Study Materials for Newcomers to Manitoba: Based on the 2011 Discover Canada Study Guide

Citizenship Study Materials for Newcomers to Manitoba: Based on the 2011 Discover Canada Study Guide Table of Contents ____________________________________________________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I TIPS FOR THE VOLUNTEER FACILITATOR II READINGS: 1. THE OATH OF CITIZENSHIP .........................................................................................1 2. WHO WE ARE ...............................................................................................................7 3. CANADA'S HISTORY (PART 1) ...................................................................................13 4. CANADA'S HISTORY (PART 2) ...................................................................................20 5. CANADA'S HISTORY (PART 3) ...................................................................................26 6. MODERN CANADA ....................................................................................................32 7. HOW CANADIANS GOVERN THEMSELVES (PART 1) .............................................. 40 8. HOW CANADIANS GOVERN THEMSELVES (PART 2) .............................................. 45 9. ELECTIONS (PART 1) ................................................................................................. 50 10. ELECTIONS (PART 2) ...............................................................................................55 11. OTHER LEVELS OF GOVERNMENT IN CANADA ................................................... 60 12. HOW MUCH DO YOU KNOW ABOUT YOUR GOVERNMENT? .............................. -

CANADA: a Profile

CANADA: a profile Motto Area From Sea to Sea 9,984,670 km² (the 2nd country in the world) Anthem O Canada Population 33,160,800 Royal anthem Canada’s flag depicts the God Save the maple leaf, the Canadian Queen Density symbol which dates back to the The Royal Canadian Mounted Capital 3.2/ km² early 18th century. Police is one of the Canadian Ottawa symbols, along with the maple leaf, beaver, Canada goose, The name Canada comes Largest city Currency common loon and the Crown. from the word kanata, Toronto Canadian dollar ($) meaning village or settlement. (CAD) Jacques Cartier, the explorer Official languages of Canada, misused this word English, French to refer to not only the village, Time zone but the entire area of the Status (UTC = Universal country. Parliamentary Coordinated Time) democracy and -3.5 to -8 federal constitutional monarchy Internet TLD The Royal Coat of Arms .ca Ice Hockey, the national winter Canada, being part of the Government sport in Canada, is represented British Commonwealth, The British by the National Hockey League shares the Royal Coat of Monarch Calling code (NHL) at the highest level. Arms with the United Governor-General +1 Kingdom of Great Britain and Prime Minister The Horseshoe Fall in Ontario Northern Ireland. is the largest component of the Niagara Falls. CANADA: A FACTFILE 1. The Official Name of the Country Canada is a country occupying most of northern North America, washed by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, by the Pacific Ocean in the west and by the Arctic Ocean in the north. -

Sea to Sea to Sea: Canada's National Marine Conservation Areas System

Canadian Heritage Patrimoine canadien Parks Canada Pares Canada SEA TO SEA Canada's National Marine Conservation Areas System Plan SEA TO SEA TO SEA Canada's National Marine Conservation Areas System Plan 1995 Parks Canada Department of Canadian Heritage ©Ministry of Supply and Services, 1995 Published under the authority of the Minister of the Department of Canadian Heritage Ottawa, 1995. Authors: Francine Mercier and Claude Mondor Editor: Sheila Ascroft Design: Sheila Ascroft and Suzanne H. Rochette Cover design: Dorothea Kappler Illustrations: Dorothea Kappler Desktop production: Suzanne H. Rochette A limited number of copies of this report are available. For more information, contact: Parks Establishment Branch National Parks Directorate Parks Canada Department of Canadian Heritage 25 Eddy Street, 4th floor Hull, QC K1A 0M5 Printed on 50% recycled paper. Issued also in French under the title: D'un ocean a Vautre: Plan de reseau des aires marines nationales de conservation du Canada Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Parks Canada Sea to sea to sea: Canada's National Marine Conservation System Plan Issued also in French under title: D'un ocean a l'autre. "Authors: Francine Mercier and Claude Mondor." —T.p. verso. ISBN 0-662-23045-0 Cat. no. R62-283/1995E 1. Marine resources conservation — Government policy — Canada. 2. Marine parks and reserves — Canada. I. Mercier, Francine M. (Francine Marie) II. Mondor, Claude (Claude A.) III. Parks Canada. IV. Title. V. Title: Canada's National Marine Conservation System Plan. GC1023.15S42 -

A Mari Usque Ad Mare: How Social Workers Achieved Labor Mobility in Canada

A Mari Usque Ad Mare: How Social Workers Achieved Labor Mobility in Canada Richard Silver, S.W., attorney Legal Counsel Ordre des travailleurs sociaux et des thérapeutes conjugaux et familiaux du Québec ASWB Spring Meeting 2015 2 Traditional Canadian social work paradigm • Educational requirements for registration similar across the country (B.S.W. or M.S.W.) • Transfer from one jurisdiction to another easy for graduates and professionals • But problems for some professionals registered through: Foreign credential recognition Substantial equivalencies Grandparenting provisions Exceptional provincial provisions 3 Agreement on Internal Trade (1994) • Federal, provincial and territorial governments seek elimination of barriers to free movement of workers, goods, services and investments • Removes existing and prevents new trade barriers and harmonises provincial standards • Reduces costs for business, increases market access and facilitates labor mobility • Chapter 7: labor mobility 4 Implementation of AIT: 1995-2008 • No deadline set by governments • Allowed reasonable time for compliance • Federal Government funded regulators to compare occupational standards and develop Mutual Recognition Agreements • Progress but no full compliance for most professions, including social workers 5 Social Work MRA (2007) • Social work university degree from approved program: • Full acceptance • Degree accepted by province: • QC, MAN, SA • Further training, supervision, exam may be required: others • International credentials – all except BC • Grandparented -

Social Studies Grade 6 Cluster 1.Qxp

GRADE Canada: A Country of Change (1867 to Present) 6 Building a Nation (1867 to 1914) 1 CLUSTER Cluster 1 Learning Experiences: Building a Overview GRADE Nation 6 (1867 to 1914) 1 CLUSTER 6.1.1 A New Nation KC-001 Explain the significance of the British North America Act. Examples: federal system of government, constitutional monarchy, British-style parliament... KC-002 Compare responsibilities and rights of citizens of Canada at the time of Confederation to those of today. Include: Aboriginal peoples, francophones, women. KL-022 Locate on a map of Canada the major landforms and bodies of water. KL-023 Locate on a map the major settlements of Rupert’s Land and the original provinces of Canada in 1867. VC-001 Appreciate the rights afforded by Canadian citizenship. 6.1.2 Manitoba Enters Confederation KH-027 Identify individuals and events connected with Manitoba’s entry into Confederation. Include: Louis Riel, Red River Resistance, Métis Bill of Rights, provisional government. KH-027F Identify the roles of Father Noël-Joseph Ritchot and Archbishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché in Manitoba’s entry into Confederation. KH-033 Identify factors leading to the entry into Confederation of Manitoba, Northwest Territories, British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, Yukon, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nunavut, and specify the year of entry. VH-012 Value the diverse stories and perspectives that comprise the history of Canada. 6.1.3 “A mari usque ad mare” [From Sea to Sea] KH-029 Describe the role of the North West Mounted Police. KH-030 Relate stories about the gold rushes and describe the impact of the gold rushes on individuals and communities. -

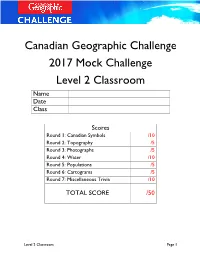

Questions Classroom.Pdf

Canadian Geographic Challenge 2017 Mock Challenge Level 2 Classroom Name Date Class Scores Round 1: Canadian Symbols /10 Round 2: Topography /5 Round 3: Photographs /5 Round 4: Water /10 Round 5: Populations /5 Round 6: Cartograms /5 Round 7: Miscellaneous Trivia /10 TOTAL SCORE /50 Level 2 Classroom Page 1 Round 1: Canadian Symbols ( /10) This round will test your knowledge of Canadian provincial, territorial, and national symbols. # Question Answer 1 The leaf of which tree appears on the Canadian flag? A) Birch B) Maple C) Elm D) Pine 2 Manitoba’s provincial animal, shown here, was once hunted nearly to extinction. What is the name of this animal? A) Plains Bison B) Wood Bison C) North American Moose D) Grizzly Bear 3 Which of the following provinces does not have a species of owl as its provincial bird? A) Quebec B) Saskatchewan C) Alberta D) British Columbia 4 An inukshuk can be found on which territorial flag? A) Nunavut B) Northwest Territories C) Yukon D) British Columbia 5 Which province’s flag features a lion and group of oak trees? A) Nova Scotia B) New Brunswick C) Newfoundland and Labrador D) Prince Edward Island Level 2 Classroom Page 2 # Question Answer 6 The common loon, which appears on the Canadian $1 coin, is the provincial bird of which province? A) Alberta B) British Columbia C) Quebec D) Ontario 7 What is the provincial mineral of Saskatchewan? A) Nickel B) Potash C) Amethyst D) Tin 8 Canada’s national motto is A Mari Usque Ad Mare. What does this translate to? A) True North Strong and Free B) From Sea to Sea C) Glorious and Free D) Our Land and Our Home 9 How many times does the fleur-de-lis appear on the Quebec flag? A) 1 B) 3 C) 4 D) 5 10 Which musical instrument appears on the Canadian coat of arms? A) Guitar B) Drum C) Harp D) Flute Level 2 Classroom Page 3 Round 2: Topography ( /5) This round will test your ability to analyze and interpret topographic maps and diagrams. -

Canadian English: a Linguistic Reader

Occasional Papers Number 6 Strathy Language Unit Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario Canadian English: A Linguistic Reader Edited by Elaine Gold and Janice McAlpine Occasional Papers Number 6 Strathy Language Unit Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario Canadian English: A Linguistic Reader Edited by Elaine Gold and Janice McAlpine © 2010 Individual authors and artists retain copyright. Strathy Language Unit F406 Mackintosh-Corry Hall Queen’s University Kingston ON Canada K7L 3N6 Acknowledgments to Jack Chambers, who spearheaded the sociolinguistic study of Canadian English, and to Margery Fee, who ranges intrepidly across the literary/linguistic divide in Canadian Studies. This book had its beginnings in the course readers that Elaine Gold compiled while teaching Canadian English at the University of Toronto and Queen’s University from 1999 to 2006. Some texts gathered in this collection have been previously published. These are included here with the permission of the authors; original publication information appears in a footnote on the first page of each such article or excerpt. Credit for sketched illustrations: Connie Morris Photo credits: See details at each image Contents Foreword v A Note on Printing and Sharing This Book v Part One: Overview and General Characteristics of Canadian English English in Canada, J.K. Chambers 1 The Name Canada: An Etymological Enigma, 38 Mark M. Orkin Canadian English (1857), 44 Rev. A. Constable Geikie Canadian English: A Preface to the Dictionary 55 of Canadian English (1967), Walter S. Avis The -

Ontario 'S Oceans

Ontario’s Oceans Ontario’s Conserving Canada’s Marine Biodiversity A Curriculum Resource for Ontario Teachers Introduction The national motto of Canada – A Mari usque ad Mare; From Sea to Sea, is certainly a fitting description of this majestic country, defined as much by its oceans as its land. Bounded by three oceans – Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic, Canada has the longest ocean coastline in the world. For the seven million Canadians living in coastal communities, oceans provide recreational, environmental, employment, income, and cultural opportunities. Canada has the potential to be a world leader in ocean conservation. The reality, however, is that the health of our marine environments is at risk or already declining. There are major declines in some fish stocks, changes in the structure of marine ecosystems, altered ocean chemistry, continued introduction of pollutants and invasive species, increasing numbers of marine species-at-risk, habitat alteration and degradation, and declining biodiversity and productivity. In recognition of the importance of oceans to biodiversity and to people, the United Nations has proclaimed May 22nd 2012 as “The International Day for Marine Biodiversity”. Most students in Ontario have little interaction with Canada’s oceans, being hundreds of kilometres away from the nearest marine coastline. (Don’t forget, Ontario is bordered on the north by marine coastline!) Despite this, or maybe because of it, students are often fascinated by sharks, puffins, and whales – all Canadian marine animals! This package provides marine biodiversity activities for both elementary and secondary students in Ontario. As a multidisciplinary topic, Ontario curriculum connections are made for life sciences, chemistry, earth sciences, and mathematics. -

CRC Bulletin, Volume 11, No. 2

Conférence religieuse canadienne Bulletin Canadian Religious Conference Volume 11, Issue 2 — Spring 2014 In this issue: 3. An Association “A mari usque ad mare” — Fr. Yvon Pomerleau, OP 15. CRC Administrative Council Meeting in Quebec — Loretteville (QC), 4. The Figures Speak for Themselves! January 8-10, 2014 SMNDA — Fr. Yvon Pomerleau, OP — Élisabeth Villemure, 16. “The Service of Leadership Has 5. CRC Administrative Council Meeting Enriched My Life” — Panel Presentation in the “West” — Saskatoon (SK), by France Croussette, AM May 1-3, 2013 — Anne Lewans, OSU 17. My Commitment in Religious Life over the Years — Panel Presentation 6. Religious Life 50 Years after Vatican II: by Gaétan Sirois, FSC Who Have We Become? — Panel The Renewal of Religious Life Presentation by Patricia Derbyshire, SCSL 18. Is Ongoing — Panel Presentation 7. “My Own Journey in Religious Life” by Gaétane Guillemette, NDPS — Panel Presentation by Joyce Harris, SSA “Live the Parable of the Good Samaritan” 8. Who Have We Become…? 19. Structural Changes, a Time of — Lorette Langlais, SBC Transformation — Panel Presentation by Margaret Patricia Brady, OSB 9. “Key Insights, Emerging Directions” 20. CRC Administrative Council Meeting — Sœur Teresita Kambeitz, OSU in Atlantic Canada — Moncton (N.-B.), March 19-21, 2014 — Rosemary MacDonald, CSM 10. CRC Administrative Council Meeting 21. The Evolution of the Service of in Ontario — Mississauga (ON), Leadership since Vatican II — Panel October 2-4, 2013 — George T. Smith, CSB Presentation by Dolores Bourque, FMA 22. “Social Justice Is an Integral Pillar 11. Life in Community: A “Voyage of My Faith” — Panel Presentation of Discovery” — Panel Presentation by Auréa Cormier, NDSC by Jean Goulet, CSC 23. -

Canada's Senate

CANADA’S SENATE: A Chamber of THOUGHT AND ACTION SBK>QB SK>Q CANADA sencanada.ca © 2018 Senate of Canada 1-800-267-7362 [email protected] 2 sencanada.ca ABOUT THE SENATE The Senate is the Upper House in Canada’s Senators also propose their own bills and generate Parliament. It unites a diverse group of discussion about issues of national importance in the accomplished Canadians in service of their country. collegial environment of the Senate Chamber, where ideas are debated on their merit. Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, famously called it a chamber of sober second thought The Senate was created to ensure Canada’s regions were but it is much more than that. It is a source of ideas, represented in Parliament. Giving each region an equal inspiration and legislation in its own right. number of seats was meant to prevent the more populous provinces from overpowering the smaller ones. Parliament’s 105 senators shape Canada’s future. Senators scrutinize legislation, suggest improvements Over the years, the role of senators has evolved. In addition and fix mistakes. In a two-chamber Parliament, the Senate to representing their region, they also advocate for acts as a check on the power of the prime minister and underrepresented groups like Indigenous peoples, cabinet. Any bill must pass both houses — the Senate visible minorities and women. and the House of Commons — before it can become law. There shall be one Parliament for Canada, consisting of the Queen, an Upper House styled the Senate, and the House of Commons. -

What Day Is National Flag Day B) National Flag Day Came Into Th On? Celebration on February 15 1996

What day is National Flag day B) National Flag Day came into th on? celebration on February 15 1996. This is because on February a) July 1st 15th 1965, the now National Flag, b) February 15th st was raised on parliament hill for c) September 1 the first time. d) November 11th Whose face is on the Canadian A) John A Macdonald, ten dollar bill? Canada’s first prime minister face is on the a) John A MacDonald current Canadian ten dollar b) William Lyon Mackenzie bill. (The purple one) King c) Wilfred Laurier d) Stephen Harper What is Canada’s Motto? A) ‘From Sea to Sea’ came to be Canada’s motto when a) A Mari Usque Ad Mare – From Sea to Sea the Canadian Pacific b) Fortis et Liber – Strong and free Railway promoters wanted c) Quaerite Prime Regnum Dei – Seek a slogan to represent ye first the Kingdom of God Canada. d) Splendor Sine Occasu – Splendour without diminishment How many Provinces and B) In Canada there are 10 Territories are there in Canada? provinces and 3 Territories, totaling to make 13. a) 51 b) 13 c) 10 d) 23 Which flag was favoured by the A) In 1964 when Lester B. Current Prime Minister at the Pearson was Prime time (Lester B. Pearson)? Minister he was in favour of this flag. In his mind it represented Canada to a a) tee with the blue representing Canada’s Motto “From Sea to Sea” b) and the maple leaf in Red which is Canada’s national symbol and colours. -

The Road to Confederation

The Road to Confederation Canada becomes a country 1860-1870 1 The Union of the Canadas • Politics and Economics • after 1845 - railway development the issue • need for government involvement • “all my politics is railroads” • true for most major politicians 2 The Union of the Canadas • “Rep by Pop” • Canada West not happy with legislative union • difficult to run things with a split • needed to have a double majority to pass laws • majority from Canada East or Canada West and majority in the combined Assembly 3 The Union of the Canadas • George Brown • need for a federal union 4 The Union of the Canadas • Toward Confederation • Reform Party - 1859 George Brown promotes federal union • a wider British North American union? • Kicked around during the 1860s • external pressures • internal strife 5 Impact of the American Civil War • Historian Frank Underhill “Somewhere on Parliament Hill in Ottawa…there should be erected a monument to this American ogre who has so often performed the function of saving us from drift and indecision.” 6 Impact of the American Civil War • Britain’s role in the Civil War • CSS Alabama • Union claimed Britain knew what was going on • wanted compensation - perhaps Canada • Trent affair • Mason and Slidell taken off ship • sent troops to Canada to defend • need for a rail link in Canada - economics and military 7 Impact of the American Civil War • The St. Alban’s raid • Oct. 1864 St. Alban’s Vermont • robbed 3 banks - $200 000 • killed and wounded 3 people • escaped to Canada • released by Canadian judge • United States military threatens retaliation if southern raiders not turned over 8 The Great Coalition • Failure of Canadian government • Reformers and Conservatives alike could not maintain a government • June 1864 - Macdonald- Tache coalition fails • Governor General Monck urged talks between Conservatives and Reformers 9 The Great Coalition • John A.