Transcript of Interview with Sharon Lebewohl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 21, 2019

Inaugural Event Knighted in 2016 Grammy® Award ® Winner Grammy Award Winner Dec. 21-29, 2019 Leonard Nimoy Thalia Theatre at Symphony Space Center for Jewish History Theatre for the New City FOR TICKETS AND MORE INFORMATION: NY Drama Desk® Award yiddishfest.org Nominee 888-YILOVEJ (888-945-6835)YI PRESENTED BY MEDIA SPONSOR Manhattan Jewish Historical Initiative YI ❤ NY YIDDISHFEST SCHEDULE OF EVENTS WEDNESDAY, DEC. 25 SATURDAY, DEC 28 Immerse yourself in the joy of Yiddish culture — laugh, sing and celebrate 2 p.m. Lecture/Reading: 2 p.m. Reading - New Jewish ❤ the very essence of Hanukkah – at YI New York YiddishFest 2019, Exploring God of Vengeance: Voices: Selections from ‘A happening throughout New York City, Dec. 21-29. Multiple Jewish cultural The Basis of ‘Indecent’ with People’ by L M Feldman organizations will come together for a series of theatrical presentations, guest speaker David Mazower Theatre for the New City Klezmer concerts, film screenings, lectures, panel discussions and (Great-grandson of Sholem famous personalities in the world of Yiddishkayt (Jewishness). Asch)Theatre for the New City 8 p.m. Concert: Frank London and Deep Singh’s Sharabi plays Bagels & Bhangra with SATURDAY, DEC. 21 MONDAY, DEC. 23 THURSDAY, DEC. 26 Special Guest Avi Hoffman Theatre for the New City 7:30 p.m. Concert Tribute: 8 p.m. Premiere Concert: 8 p.m. Concert Tribute: The Heart of Yiddish: Joe Papp at the Ballroom The Great Fyvush Finkel Remembering Isaiah Sheffer Theatre for the New City Theatre for the New City Leonard Nimoy Thalia Theatre at Symphony Space TUESDAY, DEC. -

Newsletter 19/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 19/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 190 - September 2006 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 19/06 (Nr. 190) September 2006 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, sein, mit der man alle Fans, die bereits ein lich zum 22. Bond-Film wird es bestimmt liebe Filmfreunde! Vorgängermodell teuer erworben haben, wieder ein nettes Köfferchen geben. Dann Was gibt es Neues aus Deutschland, den ärgern wird. Schick verpackt in einem ed- möglicherweise ja schon in komplett hoch- USA und Japan in Sachen DVD? Der vor- len Aktenkoffer präsentiert man alle 20 auflösender Form. Zur Stunde steht für den liegende Newsletter verrät es Ihnen. Wie offiziellen Bond-Abenteuer als jeweils 2- am 13. November 2006 in den Handel ge- versprochen haben wir in der neuen Ausga- DVD-Set mit bild- und tonmäßig komplett langenden Aktenkoffer noch kein Preis be wieder alle drei Länder untergebracht. restaurierten Fassungen. In der entspre- fest. Wer sich einen solchen sichern möch- Mit dem Nachteil, dass wieder einmal für chenden Presseerklärung heisst es dazu: te, der sollte aber nicht zögern und sein Grafiken kaum Platz ist. Dieses Mal ”Zweieinhalb Jahre arbeitete das MGM- Exemplar am besten noch heute vorbestel- mussten wir sogar auf Cover-Abbildungen Team unter Leitung von Filmrestaurateur len. Und wer nur an einzelnen Titeln inter- in der BRD-Sparte verzichten. Der John Lowry und anderen Visionären von essiert ist, den wird es freuen, dass es die Newsletter mag dadurch vielleicht etwas DTS Digital Images, dem Marktführer der Bond-Filme nicht nur als Komplettpaket ”trocken” wirken, bietet aber trotzdem den digitalen Filmrestauration, an der komplet- geben wird, sondern auch gleichzeitig als von unseren Lesern geschätzten ten Bildrestauration und peppte zudem alle einzeln erhältliche 2-DVD-Sets. -

Pressive and Photographs So Beautifully, He Is Extremely Strong in This Role,” Comments Masterson

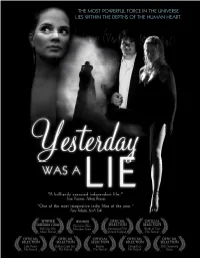

“YESTERDAY WAS A LIE” PRODUCTION INFORMATION A groundbreaking new noir film, YESTERDAY WAS A LIE is a “soulful and thought- provoking metaphysical journey” (Talking Pictures). Award-winning writer/director James Kerwin -- “one of these young guys on the edge of a digital revolution” (Soundwaves Cinema) -- crafts a thrilling, intricate detective drama that teases the boundaries of reality. Kipleigh Brown “exudes Bacall” (Slice of SciFi) as Hoyle, a girl with a sharp mind and a weak- ness for bourbon who finds herself on the trail of a reclusive genius (John Newton). But her work takes a series of unforeseen twists as events around her grow increasingly fragmented... discon- nected... surreal. With a sexy lounge singer (Chase Masterson) and a loyal partner (Mik Scriba) as her only allies, Hoyle is plunged into a dark world of intrigue and earth-shattering cosmological secrets. Haunted by an ever-present shadow (Peter Mayhew) whom she is destined to face, Hoyle discovers that the most powerful force in the universe -- the power to bend reality, the power to know the truth -- lies within the depths of the human heart. “Like Blade Runner before it, YESTERDAY WAS A LIE manages to meld film noir and science fiction into a fresh new world unlike anything we’ve seen be- fore” (iF Magazine). Also starring Nathan Mobley, Warren Davis, Megan Henning, Jennifer Slimko, and famed ra- dio personality Robert Siegel. 2 ABOUT THE PRODUCTION YESTERDAY WAS A LIE is the brainchild of writer/director James Kerwin, who made a splash in 2000 with his multi-festival-award-winning short film Midsummer. -

How to Feed Friends and Influence People

How to Feed Friends and Influence People How to Feed Friends and Influence People THE CARNEGIE DELI A Giant Sandwich, a Little Deli, a Huge Success Milton Parker Owner of The Carnegie Deli and Allyn Freeman JOHN WILEY & SONS, INC. Copyright © 2005 by Milton Parker. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. -

Celebrating NYC-ARTS

Celebrating NYC ARTS DECEMBER 2016 - YC-ARTS provides arts lovers in the tri-state area and beyond with an all-access pass to the city’s many eclectic cultural offerings. In the process, the weekly show makes a measurable impact on the institutions, artists and patrons N of these area treasures. Co-hosted by New York Emmy Award winners Philippe de Montebello and Paula Zahn, with events around town reported by News Correspondent Christina Ha, the series—now in its eighth season—showcases both world-renowned and local, community- based arts organizations with its weekly broadcast and comprehensive website. This month, viewers can enjoy an extra dose of the award-winning series with its first-ever two-hour special, Celebrating NYC-ARTS. Highlights include a feature segment at The Morgan Library & Museum, where the original manuscript of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is on display. Viewers are also taken inside the American Museum of Natural History for a look at the Origami Holiday Tree – a Big Apple holiday tradition for more than 40 years. © 2012 PAUL KOLNIK PREMIERES MONDAY, DECEMBER 19 AT 8PM “My family and I are longtime supporters of PBS, and we love NYC-ARTS in particular…the NYC-ARTS AIRS WEEKLY ON SUNDAYS AT 3PM short segments are the perfect length to give us a taste of what’s out there,” wrote Learn more at nyc-arts.org Jill Ratzan, a THIRTEEN member in New Jersey. The benefits have proven to be a two-way street, with many featured artists and venues reporting the positive impact of an appearance on NYC-ARTS. -

Introduction the Place Where Everyone Knows Your Name

Introduction ThE PlacE WhERE Everyone Knows Your Name s anything more emblematic of New York City than the overstuffed pastrami sandwich on rye? The pickled and smokedI meats sold in storefront Jewish delicatessens starting in the late nineteenth century became part of the heritage of all New Yorkers. But they were, of course, especially important to Jews; the history of the delicatessen is the history of Jews eating themselves into Americans. The skyscraper sandwich became a hallmark of New York. But it also became a potent symbol of affluence, of success, and of the attainment of the Ameri- can Dream. As the slogan for Reuben’s, an iconic delicatessen in the theater district boasted, “From a sandwich to a national institution.” This book traces the rise and fall of the delicatessen in Amer- ican Jewish culture. It traces the trajectory of an icon— a jour- ney that originates in the ancient world and rockets through the Middle Ages to postrevolutionary France, lands briefly on the Lower East Side, gathers steam in the tenements of the outer boroughs, and is catapulted out to the cities and suburbs of America, with a one- time detour into outer space. Along the way, we learn what happens when food takes on an ethnic col- oration and then gradually sheds that ethnic connection when it acculturates into America. 1 Merwin_2p.indd 1 7/10/15 12:35 PM 2 z Introduction We learn how Jews retained the taste and scent of brine— that of the seas that they had crossed in order to get to America and of the oceans that so many settled along, first in New York and later in Miami Beach and L.A.— in the foods that they ate. -

2016 in the United States Wikipedia 2016 in the United States from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

4/30/2017 2016 in the United States Wikipedia 2016 in the United States From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Events in the year 2016 in the United States. Contents 1 Incumbents 1.1 Federal government 1.2 Governors 1.3 Lieutenant governors 2 Events 2.1 January 2.2 February 2.3 March 2.4 April 2.5 May 2.6 June 2.7 July 2.8 August 2.9 September 2.10 October 2.11 November 2.12 December 3 Deaths 3.1 January 3.2 February 3.3 March 3.4 April 3.5 May 3.6 June 3.7 July 3.8 August 3.9 September 3.10 October 3.11 November 3.12 December 4 See also 5 References Incumbents Federal government President: Barack Obama (DIllinois) Vice President: Joe Biden (DDelaware) Chief Justice: John Roberts (New York) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2016_in_the_United_States 1/60 4/30/2017 2016 in the United States Wikipedia Speaker of the House of Representatives: Paul Ryan (RWisconsin) Senate Majority Leader: Mitch McConnell (RKentucky) Congress: 114th https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2016_in_the_United_States 2/60 4/30/2017 2016 in the United States Wikipedia Governors and Lieutenant governors Governors Governor of Alabama: Robert J. Bentley Governor of Mississippi: Phil Bryant (Republican) (Republican) Governor of Alaska: Bill Walker Governor of Missouri: Jay Nixon (Independent) (Democratic) Governor of Arizona: Doug Ducey Governor of Montana: Steve Bullock (Republican) (Democratic) Governor of Arkansas: Asa Hutchinson Governor of Nebraska: Pete Ricketts (Republican) (Republican) Governor of California: Jerry Brown Governor of Nevada: Brian Sandoval (Democratic) -

RE: GARY JOHN La ROSA

GARY JOHN LA ROSA DIRECTOR / CHOREOGRAPHER - SDC 646.408.8065 FIDDLER ON THE ROOF Conceived and Directed: o RAISING THE ROOF: A Gala Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of Fiddler on the Roof, Town Hall, NYC (with: Topol, Joshua Bell, Andrea Martin, Sheldon Harnick, Chita Rivera, Karen Ziemba, Fyvush Finkel, Jackie Hoffman, Jerry Zaks, Austin Pendleton, Pia Zadora, Jeffrey Lyons, Adrienne Barbeau, Mike Burstyn, Hal Prince and more than two dozen members of the Original Broadway and the 1971 Motion Picture casts. With an ensemble of 50 additional Fiddler alumni. o WONDER OF WONDERS: FIDDLER AT 50! SCW Cultural Arts, Great Neck, NY (Concert with commentary - with author Alisa Solomon and a cast including Bill Nolte and Lori Wilner) Director/Choreographer: o THE MUNY, St. Louis, MO / STARLIGHT THEATRE, Kansas City, MO (with Lewis J. Stadlen) (Kevin Kline Award nomination; Judy Award – Best Musical Production) o BARRINGTON STAGE COMPANY, Pittsfield, MA (with: Brad Oscar) (BroadwayWorld Awards – Best Direction - Large Theatre / Best Choreography – Large Theatre) o FULTON THEATRE, Lancaster, PA (with Stephen Berger) (HIGHEST GROSSING SHOW IN THE 150-YEAR HISTORY OF THE THEATRE) o STAGES ST. LOUIS, St. Louis, MO (with Bruce Sabath; St. Louis Circle Award nomination) o MAINE STATE MUSIC THEATRE, Brunswick, ME (1995 and 2016 seasons) o CAPE FEAR REGIONAL THEATRE, Fayetteville, NC (with: Bill Nolte) o WESTCHESTER BROADWAY THEATRE, Elmsford, NY (with: Mike Burstyn) o WEST VIRGINIA PUBLIC THEATRE, Morgantown, WV (with Spiro Malas) o PLAYHOUSE ON THE -

1 Interview with Jack Lebewohl, Second Avenue

Interview with Jack Lebewohl, Second Avenue Deli, 07/27/17 Part I, talking at table with Jonathan Boyarin and Gavriel Bellino [01/03] Bantering: JL: How do you make a flood? EJS: That’s a nice variation on the theme (an old insurance joke). EJS: With your permission, I’m going to ask you a little bit about Yiddish Theater and your brother Abe, about how he fell in love so to speak with the Yiddish Theater. Did that happen first in Europe, in Lemberg (L’viv), or did it happen after the War, because in 1954 he’s opening this Deli on Second Avenue. JL: I’ll tell you. My brother was 8 years old when World War II started. He and my mother are sent to Kazakhstan; and my father was sent to Siberia. So my brother didn’t have an opportunity to taste the Yiddish theater in Lemberg, Lvov. He definitely didn’t have an opportunity to taste the Yiddish theater in Kazakhstan. And post-War, when he got back to Poland and the D.P. camp, there was no Yiddish theater. He scrambled to stay alive; that’s all he really did. When he came to the United States, in 1950, he scrambled to make a living; he definitely didn’t have the time or money to go to the Yiddish Theater. His first exposure to “the Yiddish theater,” was on Second Avenue in 1954 when he opened up the Second Avenue Deli. Then all of a sudden he started to meet people associated with the Yiddish theater, and you got to remember, that the Yiddish theater was passed its heyday and prime. -

Emmy Award Winners

CATEGORY 2035 2034 2033 2032 Outstanding Drama Title Title Title Title Lead Actor Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Comedy Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Limited Series Title Title Title Title Outstanding TV Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actor—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title CATEGORY 2031 2030 2029 2028 Outstanding Drama Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Comedy Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. -

May 15, 2019 Restaurant Guide to New York City Here Are Evaluations

May 15, 2019 Restaurant Guide to New York City Here are evaluations of restaurants that I’ve tried in New York. You’ll see that the great majority of them receive grades of A or B. I don’t think that this is because I’m an easy grader. Rather, I generally don’t go to a place unless it has received at least a 4.0 from the generally reliable Zagat guide or I’ve gotten a recommendation from a source whose judgment I trust. Still, there are clunkers now and then. Also, I grade on a curve in the sense that a great hamburger joint and a great upscale French restaurant can both merit an A+, even though the dining experiences will be rather different. (Using the jargon of economics, I’m more or less looking at the marginal utility per dollar!) For the most part, these restaurants fall in the mid-price range (for Manhattan), roughly $40 to $60 per person, without drinks. Bon appétit! Restaurant Neighborhood Date Grade Comments 33 Greenwich Greenwich October 2017 A- Southern. Updated versions of southern food were Village outstanding. Try the shrimp and grits and the meatloaf sandwich. The service, while pleasant, was too slow and inattentive. 44& ½ Hell’s Kitchen Hell’s Kitchen November 2006 B+ American. Some of the dishes were terrific (goat cheese souffle’ appetizer), but some, like the main course duck, were only ok. November 2009 A Upgraded this to an A—everything was excellent, January 2010 A service was good, and portions were substantial. October 2017 A- Everything was good. -

Thomashefskybrochure.Pdf

1 ACT I 2 Joseph Rumshinsky Overture to Khantshe in amerike (1912) 3 Traditional “A mantl fun alt-tsaytikn shtof” (A Coat from Old-time Stu!) Ms. Blazer 4 Percy Gaunt The Bowery (1892) 5 Abraham Goldfaden “Mirele’s Romance” from Koldunye (The Sorceress) (1879) Ms. Widmann-Levy 6 Abraham Goldfaden Overture to Koldunye (1878) 7 Abraham Goldfaden “Babkelekh” from Koldunye (1878) Mr. Brancoveanu 8 Giacomo Minkowsky “Vi gefloygn kum ikh vider” (As if on Wings I Come) from Aleksander, der kroyn prints fun yerusholaim (Alexander, Crown Prince of Jerusalem) (1892) Ms. Widmann-Levy Mr. Brancoveanu 9 Louis Friedsell “Kaddish” from Der Yeshive bokher (The Yeshiva Student) (1899) Mr. Hensley 10 Arnold Perlmutter Medley from Dos pintele yid and Herman Wohl (A Little Spark of Jewishness) (1909) Words by Louis Gilrod “Pintele yid” and Boris Thomashefsky “Shtoyst zikh on” (Give a Guess) “Bar Mitzvah March” Ms. Blazer, Mr. Hensley Ms. Widmann-Levy , Mr. Brancoveanu I N T E R M I S S I O N ACT II 11 Arnold Perlmutter Reprise from Dos pintele yid and Herman Wohl 12 Louis Friedsell and Others Greenhorn Medley (1905-08) Words by Isidore Lillian Ms. Blazer 13 Nora Bayes “Who Do You Suppose Married My Sister? and Jack Norworth Thomashefsky” (1910) Mr. Tilson Thomas Joseph Rumshinsky Uptown, Downtown (1916) 14 Joseph Rumshinsky “Khantshe” from Khantshe in amerike (1912) Words by Isidore Lillian Ms. Blazer 15 Arnold Perlmutter “Lebn zol Columbus” (Long Live Columbus) and Herman Wohl from Der griner milyoner Words by Boris (The Green Millionaire) (1916) Thomashefsky Mr. Hensley Mr. Brancoveanu Unknown Incidental Music from Minke di dinstmoyd (Minke the Maid) (1917) Joseph Rumshinsky Title Song from Vi mener libn Words by Moishe Richter (The Way Men Love) (1919) Mr.