Adapting the 24-Hour Comic to an Academic Setting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories PAUL A. CRUTCHER DAPTATIONS OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS FOR MAJOR MOTION pictures, TV programs, and video games in just the last five Ayears are certainly compelling, and include the X-Men, Wol- verine, Hulk, Punisher, Iron Man, Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Watchmen, 300, 30 Days of Night, Wanted, The Surrogates, Kick-Ass, The Losers, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and more. Nevertheless, how many of the people consuming those products would visit a comic book shop, understand comics and graphic novels as sophisticated, see them as valid and significant for serious criticism and scholarship, or prefer or appreciate the medium over these film, TV, and game adaptations? Similarly, in what ways is the medium complex according to its ad- vocates, and in what ways do we see that complexity in Batman graphic novels? Recent and seminal work done to validate the comics and graphic novel medium includes Rocco Versaci’s This Book Contains Graphic Language, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics. Arguments from these and other scholars and writers suggest that significant graphic novels about the Batman, one of the most popular and iconic characters ever produced—including Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, and Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Killing Joke—can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels and traditional films. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011 r 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

An Exploration of Comics and Architecture in Post-War Germany and the United States

An Exploration of Comics and Architecture in Post-War Germany and the United States A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Ryan G. O’Neill IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Rembert Hueser, Adviser October 2016 © Ryan Gene O’Neill 2016 Table of Contents List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………...……….i Prologue……………………………………………………………………………………….....…1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………...8 Chapter 1: The Comic Laboratory…………………………………………………...…………………………………….31 Chapter 2: Comics and Visible Time…………………………………………………………………………...…………………..52 Chapter 3: Comic Cities and Comic Empires………………………………...……………………………...……..…………………….80 Chapter 4: In the Shadow of No Archive…………………………………………………………………………..…….…………114 Epilogue: The Painting that Ate Paris………………………………………………………………………………...…………….139 Works Cited…..……………………………………………………………………………..……152 i Figures Prologue Figure 1: Kaczynski, Tom (w)(a). “Skyway Sleepless.” Twin Cities Noir: The Expanded Edition. Ed. Julie Schaper, Steven Horwitz. New York: Akashic Books, 2013. Print. Figure 2: Kaczynski, Tom (w)(a). “Skyway Sleepless.” Twin Cities Noir: The Expanded Edition. Ed. Julie Schaper, Steven Horwitz. New York: Akashic Books, 2013. Print. Figure 3: Image of Vitra Feuerwehrhaus Uncredited. https://www.vitra.com/de-de/campus/architecture/architecture-fire-station Figure 4: Kaczynski, Tom (w)(a). “Skyway Sleepless.” Twin Cities Noir: The Expanded Edition. Ed. Julie Schaper, Steven Horwitz. New York: Akashic Books, 2013. Print. Introduction Figure 1: Goscinny, René (w), Alberto Uderzo (i). Die Trabantenstadt. trans. Gudrun Penndorf. Stuttgart: Ehapa Verlag GmbH, 1974. Pp.28-29. Print. Figure 2: Forum at Pompeii, Vitruvius Vitrubius. The Ten Books on Architecture. trans. Morris Hicky Morgan, Ph.D., LL.D. Illustrations under the direction of Herbert Langford Warren, A.M. pp. 132. Print. Figure 3: Töpffer, Rodolphe. -

The History of Web Comics Pdf Free Download

THE HISTORY OF WEB COMICS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK T. Campbell | 192 pages | 06 Jun 2006 | Antarctic Press Inc | 9780976804390 | English | San Antonio, Texas, United States The History of Web Comics PDF Book When Alexa goes to put out the fire, her clothes get burnt away, and she threatens Sam and Fuzzy with the fire extinguisher. Columbus: Ohio State U P. Stanton , Eneg and Willie in his book 'The Adventures of Sweet Gwendoline' have brought this genre to artistic heights. I would drive back and forth between Massachusetts and Connecticut in my little Acura, with roof racks so I could put boxes of shirts on top of the car. I'll split these up where I think best using a variety of industry information. Kaestle et. The Creators Issue. To learn more or opt-out, read our Cookie Policy. Authors are more accessible to their readers than before, and often provide access to works in progress or to process videos based on requests about how they create their comics. Thanks to everyone who's followed our work over the years and lent a hand in one way or another. It was very meta. First appeared in July as shown. As digital technology continues to evolve, it is difficult to predict in what direction webcomics will develop. The History of EC Comics. Based on this analysis, I argue that webcomics present a valuable archive of digital media from the early s that shows how relationships in the attention economy of the digital realm differ from those in the economy of material goods. -

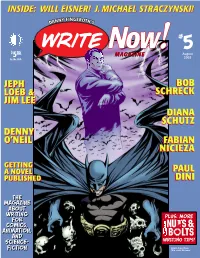

Inside: Will Eisner! J. Michael Straczynski!

IINNSSIIDDEE:: WWIILLLL EEIISSNNEERR!! JJ.. MMIICCHHAAEELL SSTTRRAACCZZYYNNSSKKII!! $ 95 MAGAAZZIINEE August 5 2003 In the USA JJEEPPHH BBOOBB LLOOEEBB && SSCCHHRREECCKK JJIIMM LLEEEE DIANA SCHUTZ DDEENNNNYY OO’’NNEEIILL FFAABBIIAANN NNIICCIIEEZZAA GGEETTTTIINNGG AA NNOOVVEELL PPAAUULL PPUUBBLLIISSHHEEDD DDIINNII Batman, Bruce Wayne TM & ©2003 DC Comics MAGAZINE Issue #5 August 2003 Read Now! Message from the Editor . page 2 The Spirit of Comics Interview with Will Eisner . page 3 He Came From Hollywood Interview with J. Michael Straczynski . page 11 Keeper of the Bat-Mythos Interview with Bob Schreck . page 20 Platinum Reflections Interview with Scott Mitchell Rosenberg . page 30 Ride a Dark Horse Interview with Diana Schutz . page 38 All He Wants To Do Is Change The World Interview with Fabian Nicieza part 2 . page 47 A Man for All Media Interview with Paul Dini part 2 . page 63 Feedback . page 76 Books On Writing Nat Gertler’s Panel Two reviewed . page 77 Conceived by Nuts & Bolts Department DANNY FINGEROTH Script to Pencils to Finished Art: BATMAN #616 Editor in Chief Pages from “Hush,” Chapter 9 by Jeph Loeb, Jim Lee & Scott Williams . page 16 Script to Finished Art: GREEN LANTERN #167 Designer Pages from “The Blind, Part Two” by Benjamin Raab, Rich Burchett and Rodney Ramos . page 26 CHRISTOPHER DAY Script to Thumbnails to Printed Comic: Transcriber SUPERMAN ADVENTURES #40 STEVEN TICE Pages from “Old Wounds,” by Dan Slott, Ty Templeton, Michael Avon Oeming, Neil Vokes, and Terry Austin . page 36 Publisher JOHN MORROW Script to Finished Art: AMERICAN SPLENDOR Pages from “Payback” by Harvey Pekar and Dean Hapiel. page 40 COVER Script to Printed Comic 2: GRENDEL: DEVIL CHILD #1 Penciled by TOMMY CASTILLO Pages from “Full of Sound and Fury” by Diana Schutz, Tim Sale Inked by RODNEY RAMOS and Teddy Kristiansen . -

UNDERSTANDING COMICS SCOTT Mccloud

UNDERSTANDING COMICS SCOTT McCLOUD What do you know about comics? Scott McCloud can take you on a journey of discovery with this wonderful book.. To use the author’s own words: ‘This is a sort of comic book about COMICS’ ‘Although there is some history in it… it’s more an examination of the ART-FORM of comics, what it’s capable of, how it works. You know, how do we DEFINE comics, what are the BASIC ELEMENTS of comics, how does the mind PROCESS the language of comics – that sort of thing. I have a chapter on CLOSURE – all about what happens BETWEEN the panels, there’s one on how TIME flows through comics, another on the interaction of WORDS and PICTURES and STORYTELLING. I even put together a new COMPREHENSIVE THEORY of the CREATIVE PROCESS and its implications for comics and for ART IN GENERAL’ Contents: Chapter 1 - SETTING THE RECORD STRAIGHT Chapter 2 - THE VOCABULARY OF COMICS Chapter 3 - BLOOD IN THE GUTTER Chapter 4 - TIME FRAMES Chapter 5 - LIVING IN LINE Chapter 6 - SHOW AND TELL Chapter 7 - THE SIX STEPS Chapter 8 - A WORD ABOUT COLOUR Chapter 9 - PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER “In one lucid, well-designed chapter after another, he guides us through the elements of comics style, and … how words combine with pictures to work their singular magic. When the 215 page journey is finally over, most readers will find it difficult to look at comics in quite the same way ever again.” ---GARY TRUDEAU NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW “If you’ve ever felt bad about wasting your life reading comics, then check out Scott McCloud’s classic book immediately. -

Writing About Comics

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators English 100-v: Writing about Comics From the wild assertions of Unbreakable and the sudden popularity of films adapted from comics (not just Spider-Man or Daredevil, but Ghost World and From Hell), to the abrupt appearance of Dan Clowes and Art Spiegelman all over The New Yorker, interesting claims are now being made about the value of comics and comic books. Are they the visible articulation of some unconscious knowledge or desire -- No, probably not. Are they the new literature of the twenty-first century -- Possibly, possibly... This course offers a reading survey of the best comics of the past twenty years (sometimes called “graphic novels”), and supplies the skills for reading comics critically in terms not only of what they say (which is easy) but of how they say it (which takes some thinking). More importantly than the fact that comics will be touching off all of our conversations, however, this is a course in writing critically: in building an argument, in gathering and organizing literary evidence, and in capturing and retaining the reader's interest (and your own). Don't assume this will be easy, just because we're reading comics. We'll be working hard this semester, doing a lot of reading and plenty of writing. The good news is that it should all be interesting. The texts are all really good books, though you may find you don't like them all equally well. The essays, too, will be guided by your own interest in the texts, and by the end of the course you'll be exploring the unmapped territory of literary comics on your own, following your own nose. -

On Jack's Revisions and Transfictional Crossing from Fables To

Second-degree Rewriting Strategies: On Jack’s Revisions and Transfictional Crossing from Fables to Jack of Fables Christophe Dony Introduction Bill Willingham, Mark Buckingham, et al.’s Vertigo series Fables (2002-2015), as its name suggests, revolves around the present-day lives of known fables, legends, and folk- and fairytale characters such as Snow White, Mowgli, Cinderella, and the Big Bad Wolf (Bigby) after they have been forced to leave their magical “native” fairytale homelands. As a result of their forced migration, these folk- and fairytale characters—who are referred to as Fables in the series—have found refuge in “our reality,” in which they have established a New York stronghold. This refugee facility of sorts for fictional characters is known as Fabletown; it is magically protected and concealed from humans who are, consequently, unable to detect the presence of Fables in the “real world.” This process of re-narrativization1 governing Fables, i.e. how known characters and their attendant storyworlds are re-configured in a new narrative, goes hand in hand with genre- meshing practices. Fables’ characters are articulated in other “pulpy” genres and settings than those they are generally associated with, i.e. the fairytale and the marvelous. As comics critic and narratologist Karin Kukkonen explains at length in her examination of comics storytelling strategies (see Kukkonen, Contemporary Comics Storytelling 74-86), Fables meshes fairytale traditions and narratives with, for example, noir/detective fiction in the first story arc “Legends in Exile” (Fables #1-5), and with the political fable/thriller canvas of George Orwell’s Animal Farm in the series’ eponymous story arc (Fables # 6-10). -

PDF Download Reinventing Comics How Imagination and Technology

REINVENTING COMICS HOW IMAGINATION AND TECHNOLOGY ARE REVOLUTIONIZING AN ART FORM 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Scott McCloud | 9780060953508 | | | | | Reinventing Comics How Imagination and Technology Are Revolutionizing an Art Form 1st edition PDF Book That said, this is a fascinating book for a number of reasons. TM: You made a point in Understanding Comics about how time equals space in comics. But there is a stunning jewel in the surrounding stone, and if you chipped away everything else the book would still be worth whatever you paid for it these days probably like a quarter for this chapter alone. We have in stock every item we list. This is a very long book, so people have time to adjust to my style. Whereas Understanding Comics was a timeless philosophical study for the sake of the art, Reinventing Comics moors itself firmly in the late 90s, exhaustively studying the history and industry of comics as it stood in the 90s and how it may shape up in the then-future. SM: I agree with you to an extent about there being a fundamental reader participation component to comics and that achieving that transparency in comics is a lot harder than it is in novels. But I was looking for a strong emotional effect. As others have noted, "Reinventing Comics" is more a product of its time and thus less timeless than McCloud's "Understanding Comics. May 09, zilby rated it it was ok Shelves: kw. That I put enough speed bumps [in] the growing complexity of those pages, that people would more naturally slow down. -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

Cohn, Neil. "Un-Defining 'Comics.'" International Journal of Comic Art, Vol

Cohn, Neil. "Un-Defining 'Comics.'" International Journal of Comic Art, Vol. 7 (2). October 2005. Un-Defining “Comics”: Separating the cultural from the structural in “comics” By Neil Cohn Perhaps the most befuddling and widely debated point in comics scholarship lies at its very core, namely, the definition of “comics” itself. Most arguments on this issue focus on the roles of a few distinct features: images, text, sequentiality, and the ways in which they interact. However, there are many other aspects of this discussion that receive only passing notice, such as the industry that produces comics, the community that embraces them, the content which they represent, and the avenues in which they appear. The complex web of categorization that these issues create makes it no wonder that defining the very term “comics” becomes difficult and is persistently wrought with debate. This piece offers a dissection of the defining features that “comics” encompass, with aims to understand both what those features and the term “comics” really mean across both cultural and structural bounds. Un-defining Comics The most prominent positions of debate in this issue focus on the “form” or “medium” of comics. Simply, comics consist of images and text, most often with the images in sequence. However, comics utilize these forms in a variety of different ways. In most, a sequence of images clearly exists to define a narrative, integrating text throughout, though this is not the only interplay between these elements. Single panel comics such as The Family Circus and The Far Side have been fully recognized as comics for decades.