Woodstock Scholarship an Interdisciplinary Annotated Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Music Sustainable: the Ac Se of Marketing Summer Jamband Festivals in the U.S., 2010 Melissa A

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 8-2012 Making Music Sustainable: The aC se of Marketing Summer Jamband Festivals in the U.S., 2010 Melissa A. Cary Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Cary, Melissa A., "Making Music Sustainable: The asC e of Marketing Summer Jamband Festivals in the U.S., 2010" (2012). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1206. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1206 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAKING MUSIC SUSTAINABLE: THE CASE OF MARKETING SUMMER JAMBAND FESTIVALS IN THE U.S., 2010 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Geography and Geology Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science By Melissa A. Cary August 2012 I dedicate this thesis to the memory my grandfather, Glen E. Cary, whose love and kindness is still an inspiration to me. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS During the past three years there have been many people who have supported me during the process of completing graduate school. First and foremost, I would like to thank the chair of my thesis committee, Dr. Margaret Gripshover, for helping me turn my love for music into a thesis topic. -

She Has Good Jeans: a History of Denim As Womenswear

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2018 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2018 She Has Good Jeans: A History of Denim as Womenswear Marisa S. Bach Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018 Part of the Fashion Design Commons, and the Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Bach, Marisa S., "She Has Good Jeans: A History of Denim as Womenswear" (2018). Senior Projects Spring 2018. 317. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018/317 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. She Has Good Jeans: A History of Denim as Womenswear Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Arts of Bard College by Marisa Bach Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2018 Acknowledgements To my parents, for always encouraging my curiosity. To my advisor Julia Rosenbaum, for guiding me through this process. You have helped me to become a better reader and writer. Finally, I would like to thank Leandra Medine for being a constant source of inspiration in both writing and personal style. -

Hawaii Marine Night Landing Volume 28, Number 4 January 28, 1999 Island Hopping A-5 B-1

Hawaii Marine Night Landing Volume 28, Number 4 January 28, 1999 Island Hopping A-5 B-1 . 1/3 gets ambush aining Pfc. Otto C. Pleil-Muele Combat Correspondent Hidden behind brush. Marines frOm A Company, 1st Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment, surprised their enemy with a flurry of lead, then jumped from their hid- ing places and stormed the enemy with a fiery attack. Though the Marines were only filling target dummies full of holes, the ambush training they were getting Jan. 21 at the rifle range here was important, according to many A Co. Marines. "This training is advanced and it will help me get better in my (military occupa- tional specialty)," said Pfc. Carmine Costanzo, a rifleman with 1st Platoon, A 4 Co. '"It's going to help me know what I have to do in combat." Unlike -similar ambush exercises in the 11 past, this one featured a moving sled with target dummies that Marines aimed at res,""'''14,,''' from nearly 200 yards down range. "The whole intent was to give Marines '49411*4..'4% something to shoot- at besides pop-up tar- ill Photo by Pk. Otto C. Ploil-Muete See 1/3, A-4 Marines of A Co., 1/3, await their opponents in a practice ambush exercise at MCB Hawaii Kaneohe Bay Jan. 21. Anthrax K-Bay Marines fire vaccine heavy weapons in Japan is safe Lance Cpl. Erickson J. Barnes "Coming here allows us the opportunity to fire these Camp Fuji Correspondent Commandant of the Marine Corps weapons at greater distances and affords us to be more-effec- CAMP FUJI, Japan - Nearly freezing temperatures tive with indirect fire," said Golden. -

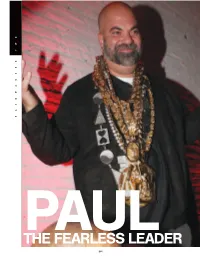

The Fearless Leader Fearless the Paul 196

TWO RAINMAKERS PAUL THE FEARLESS LEADER 196 ven back then, I was taking on far too many jobs,” Def Jam Chairman Paul Rosenberg recalls of his early career. As the longtime man- Eager of Eminem, Rosenberg has been a substantial player in the unfolding of the ‘‘ modern era and the dominance of hip-hop in the last two decades. His work in that capacity naturally positioned him to seize the reins at the major label that brought rap to the mainstream. Before he began managing the best- selling rapper of all time, Rosenberg was an attorney, hustling in Detroit and New York but always intimately connected with the Detroit rap scene. Later on, he was a boutique-label owner, film producer and, finally, major-label boss. The success he’s had thus far required savvy and finesse, no question. But it’s been Rosenberg’s fearlessness and commitment to breaking barriers that have secured him this high perch. (And given his imposing height, Rosenberg’s perch is higher than average.) “PAUL HAS Legendary exec and Interscope co-found- er Jimmy Iovine summed up Rosenberg’s INCREDIBLE unique qualifications while simultaneously INSTINCTS assessing the State of the Biz: “Bringing AND A REAL Paul in as an entrepreneur is a good idea, COMMITMENT and they should bring in more—because TO ARTISTRY. in order to get the record business really HE’S SEEN healthy, it’s going to take risks and it’s going to take thinking outside of the box,” he FIRSTHAND told us. “At its height, the business was run THE UNBELIEV- primarily by entrepreneurs who either sold ABLE RESULTS their businesses or stayed—Ahmet Ertegun, THAT COME David Geffen, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert FROM ALLOW- were all entrepreneurs.” ING ARTISTS He grew up in the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, surrounded on all sides TO BE THEM- by music and the arts. -

Burning Man's Mathematical Underbelly

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2018 Burning Man’s Mathematical Underbelly Seth S. Cottrell CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/306 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Burning Man’s Mathematical Underbelly A math degree can take you to a lot of places, both physically and figuratively, and if you play your cards right, you too can argue counterfactual definiteness with a shaman. First in 2008, and several times since, a fellow math PhD and I traveled to the Burning Man art festival to sit in the desert and talk with the locals about whatever they happened to be curious about. Burning Man began in 1986, when a group of people (who would argue endlessly over any finite list of their names) decided to assemble annually on a San Francisco beach and burn a wooden human effigy. In 1990, membership and a lack of fire permits forced Burning Man to combine with Zone #4, a “Dadaist temporary autonomous zone” piloted by the Cacophony Society, in the Black Rock Desert 110 miles outside of Reno, Nevada. Figure 1: Although The Man itself changes very little from year to year, his surroundings do. In this version from 2009, he’s surrounded by a forest of two by fours. -

Gets Taste of Fame Casualties

Inside ROLLER HOCKEY MILITARY Doer's Profile A-8 PLAYOFFS APPRECIATION WEEK Military Appreciation Week B-1 EVENTS Sports Standings B-3 B-1 B-1 Vol. 27, No. 18 Serving the base of choice for the 21st century 14, 1998 4th Force Recon gets taste of fame Cpl. Barry Melton wanted these Marines to put their Combat Correspondent best faces forward." A Marine sniper slips into position The recon Marines developed a like a cheetah preparing to dash out scenario for Hagi and gave the best to attack his prey. With sweat trick- spin on how they would do it as a ling from his cheeks, he hears foot- unit, said GySgt. Michael Gallager, steps getting closer. the operations chief at 4th Force. As he sights in on his objective, he Hagi was treated to Marines partic- attempts to see if the enemy is with- ipating in scuba exercises, scout in his effective range of fire. snipers, a four-man jump from a However, to the Marine's surprise, CH-53D and recon Marines on he sees the intruders mean no harm patrol. at all. They just want to make him Recon Marines took Hagi through famous. a jump brief, slapped a parachute Marines from 4th Force pack on his back and let him get a Reconnaissance Company here feel for what it's like to prepare for were thrown into the limelight a jump. Thursday when Guy Hagi, a news "Any good exposure for the mili- broadcaster with KHNL Channel 8 tary is good by me," Gallager said. -

Floor Plans for First and Third Floors of the Newly-Leased Building

VOLUME 78, ISSUE 6 For the Students and the Community November 13, 2000 Honors College Prvsident Speaks at Leadership Weekend Gets Approval By Adam Ostaszewski "The department has not had 3. great News Editor history at Baruch- in fact it's had a bad one." said Regan. "Mv goal is to Baruch and Beyond ~ - ~ Addressing a crowd of more than strengthen it." Regan even alluded to By Edward Ellis roo student leaders at the 17th annu the department's initiative to add a Contributing Writer al Leadership Weekend. Baruch Caribbean Studies department. President Edward Regan responded The president also addressed sever The City University of New York to the recent controversy surrounding al other issues on a wide variety of has begun recruiting 100 students to the resignation ofBlack and Hispanic topics. ranging from the new building participate in the first-ever Honors Studies Department Chair Arthur to fundraising to his vision for set College. The $5 million project is _._---Lewin.~ Baruch. to begin in the fall 200I. The pro Regan failed to address the resigna- Regan expects that Baruch wi II gram will target students with at tion of Lewin, but mentioned the continue to improve in every way. He .least a 1350 SAT score in addition to recent resignation on another profes noted that the SAT scores of incom other criteria: sor of the same department. "She ing freshmen. as well as starting Members of the Honors College resigned against my urging," said salaries for Baruch graduates are on will study at Baruch. Brooklyn. City, Regan, referring to Professor Martha the rise. -

Consumer Cynicism: Developing a Scale to Measure Underlying Attitudes Influencing Marketplace Shaping and Withdrawal Behaviours Amanda E

bs_bs_banner International Journal of Consumer Studies ISSN 1470-6423 Consumer cynicism: developing a scale to measure underlying attitudes influencing marketplace shaping and withdrawal behaviours Amanda E. Helm1, Julie Guidry Moulard2 and Marsha Richins3 1Division of Business, Xavier University of Louisiana, New Orleans, LA 70125, USA 2College of Business, Louisiana Tech University, Ruston, LA 71272, USA 3Department of Marketing, College of Business, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA Keywords Abstract Consumer activism, consumer rebellion, consumer cynicism, consumer skepticism, This article develops the construct of consumer cynicism, characterized by a perception of consumer alienation, consumer trust. a pervasive, systemic lack of integrity in the marketplace and investigates how cynical consumers behave in the marketplace. The construct was developed based on a qualitative Correspondence study and triangulated through developing a scale and investigating antecedents and Amanda E. Helm, Division of Business, Xavier consequential marketplace behaviours. The cynicism construct is uniquely suited to explain University of Louisiana, New Orleans, LA the underlying psychological processes hinted at in practitioner perceptions of the growing 70125, USA. E-mail: [email protected] mistrust and consumer research about rebellion behaviours, as well as to offer insight on consumers’ response to the increasingly sophisticated market. Previous research has doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12191 offered a glimpse of extreme rebellion behaviours such -

Tennessee, United States of America Destination Guide

Tennessee, United States of America Destination Guide Overview of Tennessee Key Facts Language: English is the most common language spoken but Spanish is often heard in the south-western states. Passport/Visa: Currency: Electricity: Electrical current is 120 volts, 60Hz. Plugs are mainly the type with two flat pins, though three-pin plugs (two flat parallel pins and a rounded pin) are also widely used. European appliances without dual-voltage capabilities will require an adapter. Travel guide by wordtravels.com © Globe Media Ltd. By its very nature much of the information in this travel guide is subject to change at short notice and travellers are urged to verify information on which they're relying with the relevant authorities. Travmarket cannot accept any responsibility for any loss or inconvenience to any person as a result of information contained above. Event details can change. Please check with the organizers that an event is happening before making travel arrangements. We cannot accept any responsibility for any loss or inconvenience to any person as a result of information contained above. Page 1/8 Tennessee, United States of America Destination Guide Travel to Tennessee Climate for Tennessee Health Notes when travelling to United States of America Safety Notes when travelling to United States of America Customs in United States of America Duty Free in United States of America Doing Business in United States of America Communication in United States of America Tipping in United States of America Passport/Visa Note Page 2/8 Tennessee, United States of America Destination Guide Airports in Tennessee Memphis International (MEM) Memphis International Airport www.flymemphis.com Location: Memphis The airport is situated seven miles (11km) southeast from Memphis. -

Big Sur for Other Uses, See Big Sur (Disambiguation)

www.caseylucius.com [email protected] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Big Sur For other uses, see Big Sur (disambiguation). Big Sur is a lightly populated region of the Central Coast of California where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. Although it has no specific boundaries, many definitions of the area include the 90 miles (140 km) of coastline from the Carmel River in Monterey County south to the San Carpoforo Creek in San Luis Obispo County,[1][2] and extend about 20 miles (30 km) inland to the eastern foothills of the Santa Lucias. Other sources limit the eastern border to the coastal flanks of these mountains, only 3 to 12 miles (5 to 19 km) inland. Another practical definition of the region is the segment of California State Route 1 from Carmel south to San Simeon. The northern end of Big Sur is about 120 miles (190 km) south of San Francisco, and the southern end is approximately 245 miles (394 km) northwest of Los Angeles. The name "Big Sur" is derived from the original Spanish-language "el sur grande", meaning "the big south", or from "el país grande del sur", "the big country of the south". This name refers to its location south of the city of Monterey.[3] The terrain offers stunning views, making Big Sur a popular tourist destination. Big Sur's Cone Peak is the highest coastal mountain in the contiguous 48 states, ascending nearly a mile (5,155 feet/1571 m) above sea level, only 3 miles (5 km) from the ocean.[4] The name Big Sur can also specifically refer to any of the small settlements in the region, including Posts, Lucia and Gorda; mail sent to most areas within the region must be addressed "Big Sur".[5] It also holds thousands of marathons each year. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available.