Chattan Conflicting Statements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

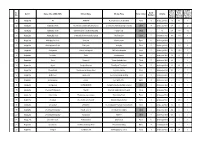

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur City District from 12.06.2016 to 18.06.2016

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur City district from 12.06.2016 to 18.06.2016 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 KOLAPPULLY HOUSE, 2078/16 U/S TOWN EAST 12.06.2016 M K AJAYAN, SI BAILED BY 1 RAGESH K R RAJAN 29 MALE MULAYAM P O, DIVANJIMOOLA 15(C) R/W 63 PS (THRISSUR at 00.15 OF POLICE POLICE VALAKKAVU ABKARAI ACT CITY) AMBATT HOUSE, 2079/16 U/S TOWN EAST 12.06.2016 M K AJAYAN, SI BAILED BY 2 VARGHESE A T THOMAS 46 MALE MULAYAM P O , DIVANJIMOOLA 15(C) R/W 63 PS (THRISSUR at 00.22 OF POLICE POLICE VALAKKAVU ABKARAI ACT CITY) MELAYIL HOUSE, 2080/16 U/S TOWN EAST RAMACHAND 12.06.2016 M K AJAYAN, SI BAILED BY 3 RAMAN 47 MALE MULAYAM P O , DIVANJIMOOLA 15(C) R/W 63 PS (THRISSUR RAN at 00.30 OF POLICE POLICE VALAKKAVU ABKARAI ACT CITY) MULLOOKKARAN 2081/16 U/S T OWN EAST 12.06.2016 M.K. AJAYAN, BAILED BY 4 SHIJI RAPPAI 39 MALE HOUSE, MULAYAM DIVANJIMOOLA 15(C) R/W 63 PS (THRISSUR AT 00.29 SI OF POLICE POLICE VALAKKAVU ABKARAI ACT CITY) PALUKKASSERY 2082/16 U/S TOWN EAST CHANDRASEKH 12.06.2016 M K AJAYAN, SI BAILED BY 5 RAJKUMAR 48 MALE HOUSE, MULAYAM P DIVANJIMOOLA 15(C) R/W 63 PS (THRISSUR ARAN at 00.50 OF POLICE POLICE O , VALAKKAVU ABKARAI ACT CITY) THACHATTIL HOUSE,NEAR 2084/16 U/S TOWN EAST V.K. -

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

Vasisthas Yoga Free Download

VASISTHAS YOGA FREE DOWNLOAD Swami Venkatesananda | 780 pages | 02 Mar 1993 | State University of New York Press | 9780791413647 | English | Albany, NY, United States Vasistha’s Yoga Gautam ed. Princeton University Press. In the first one, he was a Manasputra mind born son of Brahma. He shared with us, that these were HIS very special, precious books that he was studying in his own personal life. Atreya in suggested that the text must have preceded Gaudapada and Adi Shankarabecause it does not use their terminology, but does mention many Buddhist terms. The practice of atma-vichara"self-enquiry," described in the Yoga Vasisthahas been popularised due to the influence of Ramana Maharshi, who Vasisthas Yoga strongly influenced by Vasisthas Yoga text. Yoga Vasistha teachings are structured as stories and fables, [5] with a philosophical foundation similar to those Vasisthas Yoga in Advaita Vedanta[6] is particularly associated with drsti-srsti subschool of Advaita which holds that the "whole world of things is the object of mind". Lochtefeld He sat in the center of the huge stage, with a pile of books spread across the coffee table in front of him. This is one of the longest Hindu texts in Sanskrit after the Mahabharataand an important text of Yoga. They are not to be taken Vasisthas Yoga, nor is their significance to be stretched beyond the intention. Vasisthas Yoga Yajurveda Samaveda Atharvaveda. There are jewels in this scripture, but they must be mined. Moksha Moksha Anubhava Turiya Sahaja. Views Read Edit View history. Moksha Anubhava Turiya Sahaja. These have an embedded message of transcending "all thoughts of bigotry ", suggesting a realistic approach of mutual "coordination and harmony" between two rival religious ideas by abandoning disputed ideas from each and finding the complementary spiritual core in both. -

The Heart of Kerala!

Welcome to the Heart of Kerala! http://www.neelambari.co.in w: +91 9400 525150 [email protected] f: http://www.facebook.com/NeelambariKerala Overview Neelambari is a luxurious resort on the banks of Karuvannur puzha (river). It is constructed in authentic Kerala style and evokes grandeur and tradition. The central building consists of a classical performance arena (Koothambalam) and a traditional courtyard (Nalukettu). The cottages are luxurious with their own private balconies, spacious and clean bathrooms and well appointed bedrooms (each unit has a space of more than 75 sqm). Neelambari is situated in a very serene atmosphere right on the bank of a river, in a quiet, verdant village in central Kerala. There are several natural and historical attractions in the vicinity. Despite its rural charm, the facility is well connected, being less than an hour drive from Cochin International Airport. It is also easily accessible by rail and road and the nearest city is Thrissur, just 13 kms away. The facility offers authentic Ayurveda treatment, Yoga lessons, nature and village tourism, kayak and traditional boat trips in the river as well as traditional cultural performances in its Koothambalam. http://www.neelambari.co.in w: +91 9400 525150 [email protected] f: http://www.facebook.com/NeelambariKerala Our location Neelambari is located in Arattupuzha, a serene little village in the outskirts of Thrissur City. Thrissur has a rightful claim as the cultural capital of Kerala for more reasons than one. A host of prestigious institutions that assiduously preserve and nurture the cultural traditions of Kerala such as the Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Academy, Kerala Sahitya Academy, Kerala Lalitha Kala Academy, Kerala Kalamandalam, Unnayi Warrier Kalanilayam are located in Thrissur. -

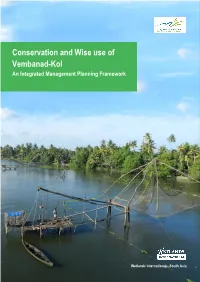

Conservation and Wise Use of Vembanad-Kol an Integrated Management Planning Framework

Conservation and Wise use of Vembanad-Kol An Integrated Management Planning Framework Wetlands International - South Asia Wetlands International – South Asia Mangroves for the Future WISA is the South Asia Programme of MFF is a unique partner- led initiative to Wetlands International, a global organization promote investment in coastal ecosystem dedicated to conservation and wise use of conservation for sustainable wetlands. Its mission is to sustain and development. It provides a collaborative restore wetlands, their resources and platform among the many different biodiversity. WISA provides scientific and agencies, sectors and countries who are technical support to national governments, addressing challenges to coastal wetland authorities, non government ecosystem and livelihood issues, to work organizations, and the private sector for towards a common goal. wetland management planning and implementation in South Asia region. It is MFF is led by IUCN and UNDP, with registered as a non government organization institutional partners : CARE, FAO, UNEP, under Societies Registration Act and steered and Wetlands International and financial by eminent conservation planners and support from Norad and SIDA wetland experts. Wetlands International-South Asia A-25, (Second Floor), Defence Colony New Delhi – 110024, India Telefax: +91-11-24338906 Email: [email protected] URL: http://south-asia.wetlands.org Conservation and Wise Use of Vembanad-Kol An Integrated Management Planning Framework Wetlands International – South Asia December 2013 Wetlands International - South Asia Project Team Acknowledgements Dr. Ritesh Kumar (Project Leader) Wetlands International – South Asia thanks the following individuals and organizations for support extended to management planning of Prof. E.J.James (Project Advisor) Vembanad-Kol wetlands Dr. -

Crisis Management Plan Thrissur Pooram 2018

T H R I S S U R P O O R A M Sree Vadakkunnatha Temple Thiruvambady Temple Paramekkavu Bhagathy Temple Chekbukkavu Bhagavathy Temple Kanimangalam SasthaTemple Panamukkumpally Sastha Temple Paramekkavu Bhagathy Temple Karamukku Bhagavathy Temple Laloor Bhagavathy Temple Choorakkottukavu Bhagavathy Temple Paramekkavu Bhagathy Temple Ayyanthole Bhagavathy Temple Neithalakkavu Bhagavathy Temple : Thrissur Pooram 2018 : : CHAPTER – I : [ INTRODUCTION 1.1 PURPOSE The purpose of the Crisis Management Plan for Thrissur Pooram is to set out actions to be taken by the in the event of any crisis or emergency occurring in connection with Thrissur Pooram. The Crisis Management Plan is designed to assist Crowd Management and Emergency Operations and creation of a system for protection of life and property in the event of a natural, manmade or hybrid hazard requiring emergency activation. The Crisis Management Plan provides guidance for all line departments in order to minimize threats to life and property. 1.2 SCOPE Crisis Management Plan covers all phases of crisis management right from mitigation, preparedness, emergency response, relief to recovery. The plan discusses roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder and should be used as a guide by all the concerned line departments to prepare their respective department to play these critical roles and responsibilities. 1.3 OBJECTIVE To protect the life of people who have assembled for the event and to avoid confusion among major stakeholders during emergency and to develop a basic structure for time sensitive, safe, secure, orderly and efficiently handling the crisis. Crisis Management Plan Page No: 1 : Thrissur Pooram 2018 : Aerial VIEW of THEKINKAD MAIDAN Page No: 2 Crisis Management Plan : Thrissur Pooram 2018 : CHAPTER – 2 [THRISSUR POORAM – POORAM OF CULTURAL CAPITAL 2.1 HISTORY & RITUALS OF THRISSUR POORAM Life in Kerala is punctuated by the annual festivals dedicated to village deities. -

LIST of PRIVATE LABS APPROVED by STATE for COVID TESTING AS on 21-08-2020 Cost of Tests Fixed by Government of Kerala in Private Sector

LIST OF PRIVATE LABS APPROVED BY STATE FOR COVID TESTING AS ON 21-08-2020 Cost of tests fixed by Government of Kerala in Private Sector. TYPE OF RESULT RATE( Inclusive of Tax) TEST RT-PCR CONFIRMATORY Rs 2750/- OPEN CBNAAT CONFIRMATORY Rs 3000/- TRUENAT If STEP1 is positive, require step 2 for confirmation STEP 1- Rs 1500/- STEP 1 negative is confirmatory STEP2- Rs1500/-( required only if STEP1 turns positive) ANTIGEN Positive results are confirmatory. Rs 625/- Negative results in a symptomatic person require + cost of further RT-PCR/CBNAAT/TRUENAT test RT- PCR/CBNAAT/TRUENAT if required Private Labs approved for RT-PCR open system 1. DDRC SRL Diagnostics Pvt Ltd, Panampilly Nagar, Ernakulam 2. MIMS Lab Services, Govindapuram, Kozhikode 3. Lab Services of Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences & Research Centre, AIMSPonekkara, Kochi 4. Dane Diagnostics Pvt Ltd, 18/757 (1), RC Road, Palakkad 5. Medivision Scan & Diagnostic Research Centre Pvt Ltd, Sreekandath Road, Kochi 6. MVR Cancer Centre & Research Institute, CP 13/516 B, C, Vellalaserri NIT (via), Poolacode, Kozhikode 7. Aza Diagnostic Centre, Stadium Puthiyara Road, Kozhikode 8. Neuberg Diagnostics Private Limited, Thombra Arcade, Ernakulam 9. Jeeva Specialty Laboratory, Thrissur 10. MES Medical College, Perinthalmanna, Malappuram Private Labs approved for XPERT/CBNAAT Testing 1. Amrita Institute of Medical Science, Kochi 2. Aster Medcity, Aster DM Healthcare Ltd, Kutty Sahib Road, Kothad, Cochin 3. NIMS Medicity, Aralumoodu, Neyyattinkara, Thiruvananthapuram 4. Rajagiri Hospital Laboratory Services, Rajagiri Hospital, Chunangamvely, Aluva 5. Micro Health LAbs, MPS Tower, Kozhikode 6. Believers Church Medical College Laboratory, St Thomas Nagar, Kuttapuzha P.O., Thiruvalla 7. -

Regional Transport Authority – Malappuram 7 May 2015

1 REGIONAL TRANSPORT AUTHORITY – MALAPPURAM 7 MAY 2015 AGENDA (PUBLIC) 1. REGULAR STAGE CARRIAGE PERMIT Item No. 1 G2/100796/2013 Agenda (1) To peruse the judgment from Hon. STAT MVAA No. 8/2014; Dtd. 22.01.2015. (2) To re-consider the application for regular Stage Carriage permit to operate on the route Kombankallu Colony – Manjeri Seethi Haji Memorial Bus Stand (via) Kathalakkal Colony, Pookkadi, Perumthura Colony, Perumthura School padi, Kodothkunnu SC Colony, Ucharakadavu Palam, Ucharakadavu, Chanthappadi, Hospital Padi, Melattur, Colony, Edayattur, Valarad Colony, Valarad, Choorakkavu, Pandikkad (also via Olipuzha, Kizhakke Pandikkad), Valluvangad, Nellikuth, Chola, Chengana Bye Pass Jn, Kovilakam kundu, Indira Gandhi Bus Terminal, Kacheripadi, General Hospital, Central Jn, Malamkulam as O.S- Reg. (Vehicle not Offered) Applicant : V. Subrahmannian, S/o Kunhukuttan, Valayangadi House, East Pandikkad, PO Kolaparamba, Manjeri via, Malappuram 676522 Proposed Timings Seethihaji Bus stand IGBT Bus Pandikkad Melattur Kombankallu Colony stand A D A A D A D A D 5.50am 6.15p 6.35 8.00 7.55p 7.25p 7.00 6.40 Edayattur 8.07 8.37p 9.02 9.05 9.25 11.10 11.05p 10.35p 10.05 10.10 9.45 Edayattur 11.15 11.45 12.10p 12.30 Edayattur 1.55 1.50p 1.20p 12.55p 12.35 Edayattur 2.04 2.34p 2.59p 3.19 Edayattur 5.02 4.57p 4.27p 3.55 4.02 3.35 Edayattur 5.15 5.45 6.10p 6.30 Edayattur 8.02 7.57p 7.27p 7.00 7.02 6.40 Edayattur 8.34 9.04p 9.29p 9.49 10.35 10.10p 9.50 halt Edayattur Item No. -

Ground Floor ,Nadar Building No-1371, Trichy Road ,Ciombatore

Sl.No IFSC Code Branch Name District State Branch Address Email Id Contact Number JT Trade Centre, Near X-ray Junction, TSC Road, Alleppy- 1 ESMF0001189 CHERTHALA ALAPUZHA KERALA [email protected] 9656058079 Cherthala Road, Alleppy Dist-688524, Kerala. Kainakari Building Ground Floor & First Floor 15/492D, BL-04/27 GF and 1329 sq feet First floor Near to Power 2 ESMF0001197 ALAPUZHA ALAPUZHA KERALA [email protected] 9633553111 House Shavakottapalam Ernakulam- Alapuzha Road Alapuzha PIN 688007 Geo Commercial Complex, Ground Floor VI/62,63, BL- 3 ESMF0001208 MAVELIKARA ALAPUZHA KERALA 55/17, Mitchel Junction, Haripad- Chengannur Road, [email protected] 8589905454 Mavelikara, PIN-690514 Door No 21/22, Gloria Arcade, Near R K Junction, N H 4 ESMF0001230 HARIPAD ALAPUZHA KERALA [email protected] 8589905709 66, Haripad, Alapuzha, Pin : 690514 Golden House, 820 , 8th Block, Ganapati Temple Road 5 ESMF0001172 KORAMANGALA BANGALORE KARNATAKA [email protected] 9902114807 Koramangla,Bangalore,560034 TRICHY ROAD - Ground Floor ,Nadar Building No-1371, Trichy Road 6 ESMF0001175 COIMBATORE TAMIL NADU [email protected] 7904758925 COIMBATORE ,Ciombatore,641018 38/211 A, Grace Tower, Near Edappally Bye Pass 7 ESMF0001103 EDAPALLY ERNAKULAM KERALA [email protected] 8589969687 Junction, Edappally – Ernakulam 682024 20/1170 A, Near Jacobite Church, Kottayam Road, 8 ESMF0001111 PERUMBAVOOR ERNAKULAM KERALA [email protected] 8589020431 Perumbavoor, Ernakulum 683542. Ground Floor, Pearl tower,Near Signal 9 -

Sl. No. District Name of the LSGD (CDS)

LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Sl. No Of Parcel Home Sponsored District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Rural / Urban Initiative No. Members By Unit Delivery by LSGI's (April 7) (April 7) (April 7) 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI church, Kodukulanji Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 27 40 0 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Ruchikoottu Janakiya Bhakshanasala Coir Machine Manufacturing Company Urban 4 Janakeeya Hotel 107 0 20 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Samrudhi janakeeya bhakshanashal Pazhaveedu Urban 5 10 256 171 12 4 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Community kitchen thavakkal group MCH junction Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 96 144 0 5 Alappuzha Ambalppuzha North Swaruma Neerkkunnam Rural 10 Janakeeya Hotel 0 0 0 6 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 229 6 7 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 Janakeeya Hotel 30 135 0 8 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 79 57 0 9 Alappuzha Aroor Navaruchi Vyasa charitable trust Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 38 0 0 10 Alappuzha Aryad Anagha Catering Near Aryad Panchayat Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 80 60 0 11 Alappuzha Bharanikavu Sasneham Janakeeya Hotel Koyickal chantha Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 182 0 0 12 Alappuzha Budhanoor sampoorna mooshari parampil building Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 0 0 13 Alappuzha Chambakulam Jyothis Near party office Rural 4 Janakeeya Hotel 0 0 0 14 Alappuzha Chenganoor SRAMADANAM chengannur market building complex Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 30 35 0 15 Alappuzha Chennam Pallippuram Friends Chennam pallipuram panchayath -

Kerala: Radical Reform As Development in an Indian State

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 149 RC 020 745 AUTHOR Franke, Richard W.; Chasin, Barbara H. TITLE Kerala: Radical Reform As Development in an Indian State. 2nd Edition. INSTITUTION Institute for Food and Development Policy, San Francisco, Calif. SPONS AGENCY Montclair State Coll., Upper Montclair, N.J.; National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-935028-58-7 PUB DATE 94 CONTRACT BNS-85-18440 NOTE 170p. AVAILABLE FROMFood First Books, Subterranean Company, Box 160, 265 South 5th St., Monroe, OR 97456 ($10.95). PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Caste; *Developing Nations; *Economic Development; Equal Education; Females; Foreign Countries; *Literacy; *Poverty Programs; Public Health; Resource Allocation; Rural Areas; Rural Urban Differences; *Social Action; Social Change IDENTIFIERS *India (Kerala State); Land Reform; *Reform Strategies; Social Justice; Social Movements ABSTRACT Kerala, a state in southwestern India, has implemented radical reform as a development strategy. As a result, Kerala now has some of the Third World's highest levels of health, education, and social justice. Originally published in 1989, this book traces the role that movements of social justice played in Kerala's successful struggle to redistribute wealth and power. A 21-page introduction updates the earlier edition. This book underlines the following positive lessons that the Kerala experience offers to developing countries: Radical reforms deliver benefits to the poor even when per capita incomes remain low. Popular movements and militant progressive organizations with dedicated leaders are necessary to initiate and sustain reform. Despite their other benefits, radical reforms cannot necessarily create employment or raise per capita income.