Writing Advice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top Hugo Nominees

Top 2003 Hugo Award Nominations for Each Category There were 738 total valid nominating forms submitted Nominees not on the final ballot were not validated or checked for errors Nominations for Best Novel 621 nominating forms, 219 nominees 97 Hominids by Robert J. Sawyer (Tor) 91 The Scar by China Mieville (Macmillan; Del Rey) 88 The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson (Bantam) 72 Bones of the Earth by Michael Swanwick (Eos) 69 Kiln People by David Brin (Tor) — final ballot complete — 56 Dance for the Ivory Madonna by Don Sakers (Speed of C) 55 Ruled Britannia by Harry Turtledove NAL 43 Night Watch by Terry Pratchett (Doubleday UK; HarperCollins) 40 Diplomatic Immunity by Lois McMaster Bujold (Baen) 36 Redemption Ark by Alastair Reynolds (Gollancz; Ace) 35 The Eyre Affair by Jasper Fforde (Viking) 35 Permanence by Karl Schroeder (Tor) 34 Coyote by Allen Steele (Ace) 32 Chindi by Jack McDevitt (Ace) 32 Light by M. John Harrison (Gollancz) 32 Probability Space by Nancy Kress (Tor) Nominations for Best Novella 374 nominating forms, 65 nominees 85 Coraline by Neil Gaiman (HarperCollins) 48 “In Spirit” by Pat Forde (Analog 9/02) 47 “Bronte’s Egg” by Richard Chwedyk (F&SF 08/02) 45 “Breathmoss” by Ian R. MacLeod (Asimov’s 5/02) 41 A Year in the Linear City by Paul Di Filippo (PS Publishing) 41 “The Political Officer” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 04/02) — final ballot complete — 40 “The Potter of Bones” by Eleanor Arnason (Asimov’s 9/02) 34 “Veritas” by Robert Reed (Asimov’s 7/02) 32 “Router” by Charles Stross (Asimov’s 9/02) 31 The Human Front by Ken MacLeod (PS Publishing) 30 “Stories for Men” by John Kessel (Asimov’s 10-11/02) 30 “Unseen Demons” by Adam-Troy Castro (Analog 8/02) 29 Turquoise Days by Alastair Reynolds (Golden Gryphon) 22 “A Democracy of Trolls” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 10-11/02) 22 “Jury Service” by Charles Stross and Cory Doctorow (Sci Fiction 12/03/02) 22 “Paradises Lost” by Ursula K. -

Earl Kemp: E*I* Vol. 3 No. 4

Vol. 3 No. 4 August 2004 --e*I*15- (Vol. 3 No. 4) August 2004, is published and © 2004 by Earl Kemp. All rights reserved. It is produced and distributed bi-monthly through http://efanzines.com by Bill Burns in an e-edition only. Contents -- eI15 -- August 2004 …Return to sender, address unknown….7 [eI letter column], by Earl Kemp Roaming Around Upstairs, by Jon Stopa 1950s Sleaze and the Larger Literary Scene, by Jay A. Gertzman On Writing: A Personal Journey, by Ian Williams Getting An Education, by J.G. Stinson Love in Loon, by Earl Kemp An Afterthought to Love in Loon, by Victor J. Banis Acres of Nubile Flesh, by Earl Kemp Señor Pig 2, by Earl Terry Kemp Wet Dreams in Paradiso, by Earl Kemp Thanks for Coming, by Jim Haynes "If You Could See Her Through My Eyes…..", by Earl Kemp A Poem for Ted Cogswell, by Avram Davidson Rounding up the Shaggy Dogs, by Bruce R. Gillespie Bombachos, Bigotes, and Bustos, by Avram Davidson You can tell this story as often as you want-people never get tired of it. If you have a perfectly ordinary guy walking down the street at noon, not thinking about anything, and he falls into a hole, that's bad fortune. He's down below the line. He struggles to get up out of the hole, finally makes it, and is a little happier when he is finished. He's faced something and survived. That's "Man in a Hole." --Kurt Vonnegut, "Teaching the Writer to Write," Kallikanzaros 4, March-April 1968 THIS ISSUE OF eI is dedicated to my hero Barney Rosset and to the much-missed Avram Davidson. -

TABLE of CONTENTS August 2000 Issue 475 Vol

TABLE OF CONTENTS August 2000 Issue 475 Vol. 45 No.2 CHARLES N. BROWN 33rd Year of Publication 21-Time Hugo Winner Publisher & Editor-in-Chief MAIN STORIES MARK R. KELLY Electronic Editor-in-Chief 2000 Locus Awards Winners/9 KIRSTEN GONG WONG Vinge, Marusek Win Campbell, Sturgeon Memorial Awards/10 Managing Editor Potter Phenom Continues/10 FAREN C. MILLER Warner Aspect First Novel Contest Gets Towering Response/10 CAROLYN F. CUSHMAN Resnick Wins Eiffel Tower Award/10 Editors THE DATA FILE CYNTHIA RUSCZYK Editorial Assistant SF/Scientists and the Interstellar Sail/11 EDWARD BRYANT Bertelsmann Book HQ Moves to US/11 Wildside Buys Cosm os/11 KAREN HABER Announcements/11 Worldcon Update/60 Awards News/60 MARIANNE JABLON Market News/60 Legal News/60 Rushdie Update/61 RUSSELL LETSON Readings & Signings/61 Financial N ew s/61 Book N ew s/61 JONATHAN STRAHAN Magazine News/61 POD Notes/61 Online Update/61 GARY K. WOLFE Multi-Media News/61 Publications Received/61 Contributing Editors Multi-Media Received/61 International Rights/62 Other Rights Sales/62 WILLIAM G. CONTENTO Catalogs Received/62 Computer Projects PHOTO STORIES BETH GWINN Photographer Dramatic Nebula Presentation/11 Fantasy Art on the Web/11 Locus, The Newspaper of the Science Fiction Field (ISSN 0047-4959), is published monthly, at $4.95 per copy, by INTERVIEWS Locus Publications, 34 Ridgew ood Lane, O akland CA 94611. Please send all m ail to: Locus Publications, P.O. Brian Aldiss: Young Turk to Grand Master/6 Box 13305, Oakland CA 94661. Telephone (510) 339- 9196; (510) 339-9198. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Asfacts July13.Pub

ASFACTS 2013 JULY “H EAT WAVE & H UMIDITY ” I SSUE NEBULA WINNERS ANNOUNCED The 2012 Nebula Awards were presented May 18, 2013, in a ceremony at SFWA’s 48th Annual Nebula Awards Weekend in San Jose, CA. Gene Wolfe was hon- ored with the 2012 Damon Knight Grand Master Award for his lifetime contributions and achievements in the field. A list of winners follows: First Novel: Throne of the Crescent Moon by Saladin Novel: 2312 by Kim Stanley Robinson, Novella: Ahmed, Young Adult Book: Railsea by China Miéville, After the Fall, Before the Fall, During the Fall by Nancy Novella: After the Fall, Before the Fall, During the Fall Kress, Novelette: “Close Encounters” by Andy Duncan, by Nancy Kress, Novelette: “The Girl-Thing Who Went Short Story: “Immersion” by Aliette de Bodard, Ray Out for Sushi” by Pat Cadigan, Short Story: “Immersion” Bradbury Award for Outstanding Dramatic Presentation: by Aliette de Bodard, Anthology: Edge of Infinity edited Beasts of the Southern Wild , and Andre Norton Award by Jonathan Strahan, and Collection: Shoggoths in Bloom for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy Book: Fair by Elizabeth Bear. Coin by E.C. Myers. Non-Fiction: Distrust That Particular Flavor by Carl Sagan and Ginjer Buchanan received Solstice William Gibson, Art Book: Spectrum 19: The Best in Awards, and Michael H. Payne was given the Kevin Contemporary Fantastic Art edited by Cathy Fenner & O’Donnell Jr. Service to SFWA Award. Arnie Fenner, Artist: Michael Whelan, Editor: Ellen Dat- low, Magazine: Asimov’s , and Publisher: Tor. ROGERS & D ENNING HOSTING PRE -CON PARTY RICHARD MATHESON DEAD Patricia Rogers and Scott Denning will uphold a local fannish tradition when they host the Bubonicon 45 LOS ANGELES (Associated Press) -- Richard Pre-Con Party 7:30-10:30 pm Thursday, August 22, at Matheson, the prolific sci-fi and fantasy writer whose I their home in Bernalillo – located at 909 Highway 313. -

Chapter Five: the Margins of Science Fiction: Gene Wolfe

CHAPTER FIVE THE MARGINS OF SCIENCE FICTION GENE WOLFE: IN SEARCH OF LOST SUZANNE: A LUPINE COLLAGE Mischievous Gene Wolfe’s ripping yarns—Wolfe is, in many respects, a good old-fashioned storyteller—are often also baffling, but scrupulously fair in their subtle deployment of clues and cues. Or so we tell ourselves hearteningly, bashing through thickets toward the masked designs and methods of his delicious fictions. Enigma can seem Wolfe’s raison d’étre. Addedto narrative sleight- of-handis the rich color of this erudite engineer’s cultural apparatus. His vocabulary is notoriously arcane, where naming the odd or specialized is called for, yet decently plain when straight-speaking is proper. Sf critics of the stamp of Peter Nicholls, Thomas M. Disch, and John Clute gnawed at his multi-volume masterpiece The Book of the New Sun. He hasan intimate knowledge of history and place, of Dickens and Proust. The opening scene in his first triumph, The Fifth Head of Cerberus, begins: “When I was a boy my brother David and I had to go to bed early, whether we were sleepy or not.” It is no accident that the overture of Marcel Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu (variously translated as Remembrance of Things Past and, more faithfully, In Search of Lost Time) begins: “For a long time I used to go to bed early.” This is not learned dog; it is relaxed cultivation. But beyond such knowingness, Wolfe is, as I say, a trickster and a tease. Two entire email lists, run by Ranjit Bhatnagar and archived on the Internet, have been devoted to unknotting the mysteries of his work, especially The Book ofthe New Sun and The Book ofthe Long Sun. -

An Evening to Honor Gene Wolfe

AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE Program 4:00 p.m. Open tour of the Sanfilippo Collection 5:30 p.m. Fuller Award Ceremony Welcome and introduction: Gary K. Wolfe, Master of Ceremonies Presentation of the Fuller Award to Gene Wolfe: Neil Gaiman Acceptance speech: Gene Wolfe Audio play of Gene Wolfe’s “The Toy Theater,” adapted by Lawrence Santoro, accompanied by R. Jelani Eddington, performed by Terra Mysterium Organ performance: R. Jelani Eddington Closing comments: Gary K. Wolfe Shuttle to the Carousel Pavilion for guests with dinner tickets 8:00 p.m Dinner Opening comments: Peter Sagal, Toastmaster Speeches and toasts by special guests, family, and friends Following the dinner program, guests are invited to explore the collection in the Carousel Pavilion and enjoy the dessert table, coffee station and specialty cordials. 1 AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE By Valya Dudycz Lupescu A Gene Wolfe story seduces and challenges its readers. It lures them into landscapes authentic in detail and populated with all manner of rich characters, only to shatter the readers’ expectations and leave them questioning their perceptions. A Gene Wolfe story embeds stories within stories, dreams within memories, and truths within lies. It coaxes its readers into a safe place with familiar faces, then leads them to the edge of an abyss and disappears with the whisper of a promise. Often classified as Science Fiction or Fantasy, a Gene Wolfe story is as likely to dip into science as it is to make a literary allusion or religious metaphor. A Gene Wolfe story is fantastic in all senses of the word. -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 10-1-1994 SFRA ewN sletter 213 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 213 " (1994). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 153. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SFRA Review Issue #213, September/October 1994 IN THIS ISSUE: SFRA INTERNAL AFFAIRS: President's Message (Mead) 5 Treastrrer's Report (Ewald) 6 SFRA Executive Committee Meeting Minutes (Gordon) 7 SFRA Business Meeting Minutes (Gordon) 10 Campaign Statements and Voting Instructions 12 New Members/Renewals (Evvald) 15 Letters 16 Corrections 18 Editorial (Sisson) 18 NEWS AND INFORMATION 21 SELECfED CURRENT & FORTHCOMING BOOKS 25 FEATURES Special Feattrre: The Pilgrim Award Banquet Pioneer Award Presentation Speech (Gordon) 27 Pioneer Award Acceptance Speech (Tatsumi & McCaffery) 29 Pilgrim Award Presentation Speech (Wendell) 32 Pilgrim Award Acceptance Speech (Clute) 35 REVIEWS: Nonfiction: Asimov, Isaac. 1. Asimov: A Memoir. (Gunn) 41 Cave, Hugh B. Magazines I Remember: Some Pulps, Their Editors, and What It Was Like to Write for Them. (Hall) 43 Fausett, David. Writing the New World: Irnaginary Voyages and Utopias of the Great Southern Land. -

2004 World Fantasy Awards Information Each Year the Convention Members Nominate Two of the Entries for Each Category on the Awards Ballot

2004 World Fantasy Awards Information Each year the convention members nominate two of the entries for each category on the awards ballot. To this, the judges can add three or more nominees. No indication of the nominee source appears on the final ballot. The judges are chosen by the World Fantasy Awards Administration. Winners will be announced at the 2004 World Fantasy Convention Banquet on Sunday October 31, 2004, at the Tempe Mission Palms Hotel in Tempe, Arizona, USA. Eligibility: All nominated material must have been published in 2003 or have a 2003 cover date. Only living persons may be nominated. When listing stories or other material that may not be familiar to all the judges, please include pertinent information such as author, editor, publisher, magazine name and date, etc. Nominations: You may nominate up to five items in each category, in no particular order. You don't have to nominate items in every category but you must nominate in more than one. The items are not point-rated. The two items receiving the most nominations (except for those ineligible) will be placed on the final ballot. The remainder are added by the judges. The winners are announced at the World Fantasy Convention Banquet. Categories: Life Achievement; Best Novel; Best Novella; Best Short Story; Best Anthology; Best Collection; Best Artist; Special Award Professional; Special Award Non-Professional. A list of past award winners may be found at http://www.worldfantasy.org/awards/awardslist.html Life Achievement: At previous conventions, awards have been presented to: Forrest J. Ackerman, Lloyd Alexander, Everett F. -

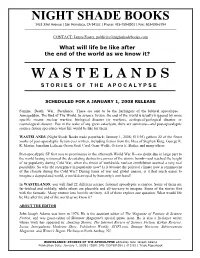

W a S T E L a N D S

NIGHT SHADE BOOKS 1423 33rd Avenue | San Francisco, CA 94122 | Phone: 415-759-8901 | Fax: 603-590-2754 _____________________________________________________________________________________ CONTACT: James Foster, [email protected] What will life be like after the end of the world as we know it? W A S T E L A N D S S T O R I E S O F T H E A P O C A L Y P S E SCHEDULED FOR A JANUARY 1, 2008 RELEASE Famine. Death. War. Pestilence. These are said to be the harbingers of the biblical apocalypse— Armageddon, The End of The World. In science fiction, the end of the world is usually triggered by more specific means: nuclear warfare, biological disaster (or warfare), ecological/geological disaster, or cosmological disaster. But in the wake of any great cataclysm, there are survivors—and post-apocalyptic science fiction speculates what life would be like for them. WASTELANDS (Night Shade Books trade paperback; January 1, 2008; $15.95) gathers 22 of the finest works of post-apocalyptic fiction ever written, including fiction from the likes of Stephen King, George R. R. Martin, Jonathan Lethem, Orson Scott Card, Gene Wolfe, Octavia E. Butler, and many others. Post-apocalyptic SF first rose to prominence in the aftermath World War II—no doubt due in large part to the world having witnessed the devastating destructive power of the atomic bomb—and reached the height of its popularity during Cold War, when the threat of worldwide nuclear annihilation seemed a very real possibility. So why the resurgence in popularity now? Is it because the political climate now is reminiscent of the climate during the Cold War? During times of war and global unease, is it that much easier to imagine a depopulated world, a world destroyed by humanity's own hand? In WASTELANDS , you will find 22 different science fictional apocalyptic scenarios. -

Lightspeed Magazine Issue 22, March 2012

Lightspeed Magazine Issue 22, March 2012 Table of Contents Editorial, March 2012 by John Joseph Adams “Cleopatra Brimstone”—Elizabeth Hand (ebook- exclusive novella) The Games—Ted Kosmatka (novel excerpt) Interview: R. A. Salvatore Interview: Ian McDonald Artist Gallery: Ed Basa Artist Spotlight: Ed Basa “The Day They Came”—Kali Wallace (SF) “My She”—Mary Rosenblum (SF) “Electric Rains”—Kathleen Ann Goonan (SF) “Test”—Steven Utley (SF) “Alarms”—S. L. Gilbow (fantasy) “The Legend of XI Cygnus”—Gene Wolfe (fantasy) “Beauty”—David Barr Kirtley (fantasy) “Halfway People”—Karen Joy Fowler (fantasy) Author Spotlight: Elizabeth Hand (ebook-exclusive) Author Spotlight: Kali Wallace Author Spotlight: Mary Rosenblum Author Spotlight: Kathleen Ann Goonan Author Spotlight: Steven Utley Author Spotlight: S. L. Gilbow Author Spotlight: David Barr Kirtley Author Spotlight: Karen Joy Fowler Coming Attractions © 2012, Lightspeed Magazine Cover Art and artist gallery images by Ed Basa. Ebook design by Neil Clarke. www.lightspeedmagazine.com Editorial, March 2012 John Joseph Adams Welcome to issue twenty-two of Lightspeed! This month, our ebook-exclusive novella is “Cleopatra Brimstone” by Elizabeth Hand. Then we have original science fiction by new writer Kali Wallace (“The Day They Came”) and Steven Utley (“Test”), and SF reprints by award-winning authors Mary Rosenblum (“My She”) and Kathleen Ann Goonan (“Electric Rains”). We also have original fantasy by S. L. Gilbow (“Alarms”) and David Barr Kirtley (“Beauty”), and fantasy reprints by bestselling author Karen Joy Fowler (“Halfway People”) and the legendary Gene Wolfe (“The Legend of XI Cygnus”). All that plus our artist showcase, our usual assortment of author spotlights, and feature interviews with R. -

Science Fiction Review 40 Geis 1981-08

SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $2.00 FALL 1981 NUMBER 40 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (,SSN “ Formerly THE ALIEN CELTIC P.O. BOX 11408 AUGUST 1981----- VOL. 10, NO 3 PORTLAND, OR 97211 WHOLE NUPBER 00 PHOf'E: (503) 282-0381 PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR PUBLISHED QUARTERLY COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. BACK COVER BY GARY WIS SINGLE COPY — $2.00 ALIEN THOUGHTS BY THE EDITOR............................................... 4 LETTERS............................................... 32 POUL ANDERSON A.J. BUDRYS interview: ROBERT SHECKLEY SHAWNA PC CARTHY CONDUCTED BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER... .7 MICHAEL MOORE GEORGE WARREN GENE WOLFE AND THEN I READ.... ALAN DEAN FOSTER INTERIOR ART---------------------------------- BY THE EDITOR............................................. 10 HARLAN ELLISON ROBERT BLOCH TIM KIRK---- . HARRY J.N. ANDRUSCHAK ALEXIS gill: THE ORYCON '80 CONVENTION SHELDON TEITELBAUM FOUR-WAY TELEPHONE CONVERSATION...12 JACK L. CHALKER ARTHUR C. CLARKE DAVID LANGFOFE ARNE FENNER— KURT REICHEL—9 HARLAN ELLISON RONALD R. LAMBERT VIK KOSTRIKIN---- 14,17,46 FRITZ LEIBER GREGORY BENFORD RICHARD TORONTO GEORGE KOCHELL—18,19,22,29,40,^, HARK WELLS JOFN SHIRLEY 44,59,65 ROBERT A.W. LOWNDES MIKE GILBERT—23,51 BRUCE CONKLIN—25 TEN YEARS AGO IN SF—Sutter, 1971 , JAPES PEQUADE----25 BY ROBERT SABELLA.................................... 17 OLE PETTERSON----26,27 OTHER VOICES.......................................43 SAM ADKINS—31,45 BOOK REVIEWS BY PAUL CHADWICK—32 THE ENGINES OF THE NIGHT DEAN R. LAMBE SUSAN LYNN TQCKER---- 33,41 ESSAYS OF SF IN THE EIGHTIES J0H4 DIPRETE KEN HAHN---- 35,55 BY BARRY N. MAI 7RFRG..............................18 DOUGLAS BARBOUR ALLEN KOSZOWSKI—48 SUE BECKMAN ROBERT BARGER---- 58 ANDREW ANDREWS SMALL PRESS NOTES GENE DE WEESE BY THE EDITOR.............................................23 STEVE LEWIS FREDERICK PATTEN CLIFFORD R.