Spotlight on Uzbekistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Administrative Management of Territories Inhabited by Kyrgyz and Kipchaks in the Kokand Khanate

EPRA International Journal of Environmental Economics, Commerce and Educational Management Journal DOI : 10.36713/epra0414 |ISI I.F Value: 0.815|SJIF Impact Factor(2020): 7.572 ISSN:2348 – 814X Volume: 7| Issue: 1| August 2020 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ADMINISTRATIVE MANAGEMENT OF TERRITORIES INHABITED BY KYRGYZ AND KIPCHAKS IN THE KOKAND KHANATE Boboev Mirodillo Kosimjon ugli Student of Fergana State University, Uzbekistan. -----------------------------------ANNOTATION-------------------------------- This article provides information about territories inhabited by Kyrgyz and Kipchaks in the Kokand Khanate, their forms of social, economic and administrative management, as well as their senior management positions. KEYWORDS: Kyrgyz, Kipchak, tribe, khan, governor, mirshab, Kokand, channel, feudal, valley. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- DISCUSSION In the first half of the XIX century, the Kokand khanate was the largest region in Central Asia. The Kokand khanate was bordered by East Turkestan in the east, the Bukhara Emirate and the Khiva Khanate in the west. The territory of the khanate in the north was completely subjugated by three Kazakh juzes and bordered by Russia. The southern borders of the khanate included mountainous areas such as Karategin, Kulob, Darvaz, Shogunan. For these regions, there will be bloody wars with the Emirate of Bukhara, which passed from hand to hand. The territory of the Kokand khanate, in contrast to the Bukhara emirate and the Khiva khanate had many wetlands, valleys and fertile lands. The center of the khanate was the Fergana Valley, where such large cities as Kokand, Margilan, Uzgen, Andizhan, and Namangan were located. Large cities such as Tashkent, Shymkent, Turkestan, Avliyota, Pishtak, Oqmasjid were also under the rule of Kokand khanate. The population of the Kokand khanate is relatively dense, about 3 million. -

OPERATION SCHEME of the Executives of Sectors, Head Offices and Secretaries of Head Offices of Tashkent Region

OPERATION SCHEME of the Executives of Sectors, Head offices and secretaries of Head offices of Tashkent Region Sector 1 – Khokim’s Head office Sector 2 – Head office secretary of the Sector 3 –Head office secretary of the Sector 4 – Head office secretary of the secretary and location Prosecutor’s Office and location Department of Internal affairs (DIA) State Tax Inspectorate and location and location Khidoyatov Davron Abdulpattakhovich Samadov Salom Ismatovich Aripov Tokhir Tulkinovich Raimov Ravshan Isakjanovich KHOKIM OF THE REGION TASHKENT REGION PROSECUTOR MAIN DEPARTMENT OF INTERNAL STATE TAX INSPECTORATE OF HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: A. Eshbaev HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: М. Egamberdiev AFFAIRS OF TASHKENT REGION TASHKENT REGION Phone number: (98) 007-30-04 Phone number: (97) 733-57-37 HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: F. HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: E. Djumabaev Location: 1, Almalik city, Tashkent region. Location: 1, Tashkent yuli, Nurafshan city. Khamitov Phone number: (93) 398-54-34 Phone of the Head office: (70) 201-07-34 +6448 Phone number: (99) 301-70-77 Location: 79 A, Babur str., Tashkent. Location: Mevazor, Kuyichirchik region. Phone of the Head office: (78) 150-49-56 Phone of the Head office: (95) 476-75 -77 Saliyev Muzaffar Kholdorbolevich Mirzayev Fakhriddin Yusupovich Amanbaev Navruz Zokirjonovich Narkhodjaev Sanjar Rashidovich KHOKIM OF NURAFSHAN CITY PROSECUTOR OF NURAFSHAN CITY DIA OF NURAFSHAN CITY NURAFSHAN CITY STATE TAX HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: О. Erbaev HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: М.Shukrullaev HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: F. INSPECTORATE Phone number: (99) 823-67-72 Phone: (97) 911-77-10 Imankulov HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: E. Igamnazarov Location: Tashkent yuli str., Nurafshan city. Location: 4A, Shon shukhrat str., Obod turmush Phone: (94) 631-49-37 Phone: (94) 930-03-73 CCU, Nurafshan city. -

Classification of Fergana Valley Chaykhana (Tea Houses)

Review Volume 11:2, 2021 Journal of Civil & Environmental Engineering ISSN: 2165-784X Open Access Classification of Fergana Valley Chaykhana (tea houses) Tursunova Dilnoza Raufovna* and Mahmudov Nasimbek Odilbekovich Department of Teacher of Feragana polytechnic institute, University of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria Abstract In this article, you will learn about the rapid development and maintenance of traditional chaykhana in Central Asia, as well as the new approaches to household and service facilities. And an architectural solution is given, taking into account modern, national and climatic, functional and traditional factors. Keywords: Chaykhana, Teahouse, Ferghana Valley, Andijan chaykhana, Market chaykhana, Sheikh Islam, Isfara Guzari, Khudoyarhon Park, Kokand, Uzbegim, Ferghana, Afrosiyab. important as working out an architectural solution of these places Introduction [1-3]. After the independence in 1995, for the first time in history the law Purpose: Fergana teahouse in the design, construction, of the Republic of Uzbekistan on “architecture and urban planning" explication, as well as socio-economic, demographic and natural- was adopted. Due to this law implementation and execution climatic conditions on architectural projects, forming the basis of numerous industry opportunities appeared and on the basis of modern requirements [2-5]. historical, cultural resources, climate, and earthquakes and in general, taking into account the circumstances of specific location 148 national state "of construction norms and rules" was figured out. Methodology It should be noted that the path of independence, especially in the Historical formation, project analysis, observations and export field of urban planning, increased attention to the construction of the requests of Fergana Valley chaykhana studied the origin, formation of the service facilities [1,2]. -

UZBEKISTAN In-Depth Review

UZBEKISTAN In-Depth Review of the Investment Climate and Market Structure in the Energy Sector 2005 Energy Charter Secretariat ENERGY CHARTER SUMMARY AND MAIN FINDINGS OF THE SECRETARIAT Uzbekistan, a Central Asian country located at the ancient Silk Road, is rich in hydrocarbon resources, especially natural gas. Proved gas reserves amount to about 1.85 trillion cubic meters, exceeding the confirmed oil reserves of about 600 million barrels nearly 20-fold on energy equivalent basis. Most of the existing oil and gas fields are in the Bukhara-Kiva region which accounts for approximately 70 percent of Uzbekistan’s oil production. The second largest concentration of oil fields is in the Fergana region. Natural gas comes mainly from the Amudarya basin and the Murabek area in the southwest of Uzbekistan, making up almost 95 percent of total gas production. The endowment with oil and gas offers considerable potential for further economic development of Uzbekistan. Its recent economic performance has been promising, with a GDP growth of above 7 percent in 2004, and an outlook for continuous robust growth in 2005 and beyond. To what extent it can be realised depends crucially on how the government will pursue its policies concerning investment liberalisation and market restructuring, including privatisation, in the energy sector. While the Uzbek authorities recognize the critical role that foreign investment plays for the exploitation of the hydrocarbon resources and the overhaul of the existing energy infrastructure progress has been relatively slow concerning the establishment of a favourable investment climate for many years. However, the Government has recently adopted a far more positive stance that has already brought about tangible results. -

Housing for Integrated Rural Development Improvement Program

i Due Diligence Report on Environment and Social Safeguards Final Report June 2015 UZB: Housing for Integrated Rural Development Investment Program Prepared by: Project Implementation Unit under the Ministry of Economy for the Republic of Uzbekistan and The Asian Development Bank ii ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DDR Due Diligence Review EIA Environmental Impact Assessment Housing for Integrated Rural Development HIRD Investment Program State committee for land resources, geodesy, SCLRGCSC cartography and state cadastre SCAC State committee of architecture and construction NPC Nature Protection Committee MAWR Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources QQL Qishloq Qurilish Loyiha QQI Qishloq Qurilish Invest This Due Diligence Report on Environmental and Social Safeguards is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 4 B. SUMMARY FINDINGS ............................................................................................... 4 C. SAFEGUARD STANDARDS ...................................................................................... -

Uzbekistan Embraced Tour Duration – 12 Days

Tour Notes Uzbekistan Embraced Tour Duration – 12 Days Tour Rating Fitness ●●●○○ | Off the Beaten Track ●●●○○ | Culture ●●●●○ | History ●●●●● | Wildlife ○○○○○ Tour Pace Busy Tour Highlights The splendour of the Museum City of Khiva. The unique art gallery at Nukus The stunning architecture of Samarkand, in particular the Registan Square. A night at a yurt camp at Lake Aydarkul Tour Map - Uzbekistan Embraced Tour Essentials Accommodation: Mix of hotels and one night in a yurt camp. Included Meals: Daily breakfast (B), plus lunches (L) and dinners (D) as shown in the itinerary. Group Size: Maximum of 12 Start Point: Tashkent End Point: Tashkent Transport: Private cars or minibuses, domestic flight and train. Countries: Uzbekistan Uzbekistan Embraced The Silk Road cities of Tashkent, Samarkand, and the Khanates of Bukhara, Khiva are all names that have resonated through the centuries, heavy with exoticism and remoteness. It’s surprising to see that most are now linked by high speed ‘Bullet Train’. Elsewhere, Amir Timur - ‘Tamerlane’ - an undefeated military genius from the 15th century, still occupies a revered place in Uzbek psyche, while more recent Soviet icons, even the hammer and sickle motifs on the subway walls, have already faded. Uzbekistan is rightly renowned as a remarkably rich repository for the past. Visiting its outstanding architectural heritage, it’s difficult to be unmoved by beauty inherent in the design and execution of mosques, minarets, mausoleums and madrassas. However, listen too for contemporary tales of national unity over ethnic division, and of political liberalisation over authoritarianism. Uzbekistan already possesses a wealth of history but its story isn’t over. -

Draft Resettlement Plan UZB: Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation

Draft Resettlement Plan February 2017 UZB: Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) Corridor 2 (Pap-Namangan-Andijan) Railway Electrification Project Prepared by the O’zbekiston Temir Yo’llari (UTY), Republic of Uzbekistan for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 3 February 2017 ) Currency unit – Uzbekistan sum (UZS) UZS1.00 = 0.000304854 $1.00 = UZS3,280.25 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank AP - Affected Person AH - Affected Household CC - Civil Code CSC- Construction Supervision Consultant DMS - Detailed Measurement Survey DLARC - District Land Acquisition and Resettlement Committee DP - Displaced Person EA - Executing Agency FGD - Focused Group Discussion GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism ha - Hectare HH - Household IA - Implementing Agency IP - Indigenous Peoples LAR - Land Acquisition and Resettlement LARP - Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan LC - Land Code MOF - Ministry of Finance PIS- - Preliminary impact assessment (PIS) PIU - Project Implementation Unit PPTA- Project Preparatory Technical Assistance RoW - Right of Way SCLRGCSC State Committee on Land Resources, Geodesy, Cartography and State Cadaster SES - Socioeconomic Survey SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement TC - Tax Code TL - Transmission Line ToR - Terms of Reference UTY - O’zbekiston Temir Yo’llari UZS - Uzbek Som NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Overtures to Chinese Highlight Nikita Talk

T 7 U 1 8 0 A T , '■m S t ^bwinard’s ^IfoUHOw. 7 / f V ^ H ld S S will meet tomorrow a t 8 :0 Stndentfi Speak U. MursilRr ^ at tha home of Mrs. John CC Schools and eoM with ___ ___ . t v : nril, 160 ^ p o l S t The R«v. Jd To Toastmasters iwow a* nlghh ’I ^ II c t the Tbner of the Hartford Chanter, 20s. WlU 1M Lasalettea Fathers Burma Mls- Chew ’N Chat Toastmasters ia « h t Manobaiitor High Cftjr o f VUIogo Charm 7 pjn. at tile aion, win i^eak and riiow slides of inuaiotaM dunonatnOod woodwind - •v - r —— ....................... ■ ________- -- AtoMi m i r TcWroatli Oenter. the mlasicm. Club will “toast the teen-agen” at and read Matiumento in a iM their meeting Wednesday at •even atsmentary Mhodla ydater- . MANCRBSTBIL c o w , WEDNESDAY, YEERVART 17, IMS 1 AuxUIaxy wUI oiMt Airman Robert B. Sales, son of WUUe’t Restaurant With -the co- day. ^ „__ '1' , ________________________ t . /laaigM a t 7:80 at th* poat home. Mr. and Mrs. Edward Sales of 24 operatimi of k^iss Helen Estes of Hie tour was tha^finri carter St., is undergoing basic the Elnglish Department at Man pliumad by the townn a l e n w l ^ Dingwall, daugh- training at Lackland Air Force chester High School, a panel c t murio dTtMutmaDt to aoquitot tha, AltiiaUe C. Dingwall; Bsuse in Texsui. Before enlistment. students has been secured to give tddldran with tha woodwlnda, ^ Cased Airman Sales attsnded Howell the fliat ot aaverol to toaoh the u, s. -

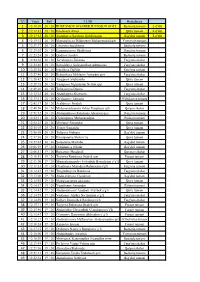

T/R 1 1-O'rin 2 2-O'rin 3 3-O'rin 4 5 6 7

T/r Vaqti Ball F.I.SH Hududingiz 1 12:10:05 20 / 20 RUSTAMOV OG'ABEK ILYOSJON OG'LI Beshariq tumani 1-o'rin 2 12:12:43 20 / 20 Ibrohimov Axror Quva tumani 2-o'rin 3 12:17:33 20 / 20 Xoshimova Sarvinoz Qobiljon qizi Bag'dod tumani 3-o'rin 4 12:19:12 20 / 20 Mamataliyeva Dildoraxon Muhammadali qizi Yozyovon tumani 5 12:21:17 20 / 20 Umarova Sug'diyona Beshariq tumani 6 12:23:02 20 / 20 Egamnazarova Shahloxon Dang'ara tumani 7 12:23:24 20 / 20 Qodirov Javohir Beshariq tumani 8 12:24:38 20 / 20 Jo'raboyeva Zebiniso Farg'ona shahar 9 12:24:46 20 / 20 Sotvoldieva Guloyim Rustambekovna Farg'ona shahar 10 12:25:54 20 / 20 Ismoilova Gullola Farg'ona tumani 11 12:27:46 20 / 20 Bektosheva Mohlaroy Anvarjon qizi Farg'ona shahar 12 12:28:42 20 / 20 Turģunov Shukurullo Quva tumani 13 12:29:18 20 / 20 Yusupova Niginabonu Ne'mat qizi Quva tumani 14 12:29:20 20 / 20 Tohirjonova Diyora Farg'ona shahar 15 12:32:35 20 / 20 Abdullayeva Shaxnoza Farg'ona shahar 16 12:33:31 20 / 20 Qo'chqorov Jahongir O'zbekiston tumani 17 12:43:17 20 / 20 Arabboyev Jòrabek Quva tumani 18 12:48:56 20 / 20 Muhammadjonova Odina Yoqubjon qizi Qo'qon shahar 19 12:51:32 20 / 20 Abdumalikova Ruhshona Abrorjon qizi Dang'ara tumani 20 12:52:11 20 / 20 G'ulomjonov Muhammadjon Rishton tumani 21 12:52:25 20 / 20 Mirzayev Samandar Quva tumani 22 12:55:03 20 / 20 Toirov Samandar Quva tumani 23 12:56:05 20 / 20 Tolipova Gulmira Bag'dod tumani 24 12:57:36 20 / 20 Ikromjonova Shohroʻza Quva tumani 25 12:57:45 20 / 20 Solijonova Marxabo Bag'dod tumani 26 12:06:19 19 / 20 Ochildinova Nilufar -

Money Transfer Offices by PIXELCRAFT Name Address Working Hours

Money transfer offices by PIXELCRAFT www.pixelcraft.uz Name Address Working hours Operating Branch Office at the Operating Branch 7, Navoi Street, Shaykhontokhur District, from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM Tashkent City, Uzbekistan No lunch time Day offs: Saturday and Sunday Office at the banking service center 616, Mannon Uygur Street, Uchtepa from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM "Beshqayragoch" District, Tashkent City, Uzbekistan No lunch time Day offs: Saturday and Sunday Office at the banking service center 77, Bobur Street, Yakkasaray District, from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM "UzRTSB" Tashkent City, Uzbekistan No lunch time Day offs: Saturday and Sunday Office at the banking service center Tashkent region, Ikbol massif, Yoshlik from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM No lunch time “Taraqqiyot” Street, 1 (Landmark: Yunusabad district, Day offs: Saturday and Sunday on the side of the TKAD, opposite the 18th quarter, the territory of the building materials market) "Tashkent" Branch Office at Tashkent branch 11A, Bunyodkor Street, Block E, from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM Chilanzar District, Tashkent City, 100043, No lunch time Uzbekistan Day offs: Saturday and Sunday Office at the banking service center 60, Katartal Street, Chilanzar District, from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM "Katartal" Tashkent City, Uzbekistan No lunch time Day offs: Saturday and Sunday Office at the banking service center 24, "Kizil Shark" Street, Chilanzar District, from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM "Algoritm" Tashkent City, Uzbekistan No lunch time Day offs: Saturday and Sunday Office at the banking service center 8, Beshariq -

Uzbekistan: Recent Developments and U.S

Order Code RS21238 Updated May 2, 2005 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Uzbekistan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary Uzbekistan is an emerging Central Asian regional power by virtue of its relatively large population, energy and other resources, and location in the heart of the region. It has made limited progress in economic and political reforms, and many observers criticize its human rights record. This report discusses U.S. policy and assistance. Basic facts and biographical information are provided. This report may be updated. Related products include CRS Issue Brief IB93108, Central Asia, updated regularly. U.S. Policy1 According to the Administration, Uzbekistan is a “key strategic partner” in the Global War on Terrorism and “one of the most influential countries in Central Asia.” However, Uzbekistan’s poor record on human rights, democracy, and religious freedom complicates its relations with the United States. U.S. assistance to Uzbekistan seeks to enhance the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and security of Uzbekistan; diminish the appeal of extremism by strengthening civil society and urging respect for human rights; bolster the development of natural resources such as oil; and address humanitarian needs (State Department, Congressional Presentation for Foreign Operations for FY2006). Because of its location and power potential, some U.S. policymakers argue that Uzbekistan should receive the most U.S. attention in the region. 1 Sources for this report include the Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS), Central Eurasia: Daily Report; Eurasia Insight; RFE/RL Central Asia Report; the State Department’s Washington File; and Reuters, Associated Press (AP), and other newswires. -

Nikita P. Rodrigues, M.A. 3460 14Th St NW Apt 131 Washington, DC 20010 [email protected] (606) 224-2999

Nikita P. Rodrigues 1 Nikita P. Rodrigues, M.A. 3460 14th St NW Apt 131 Washington, DC 20010 [email protected] (606) 224-2999 Education August 2013- Doctoral Candidate, Clinical Psychology Present Georgia State University Atlanta, Georgia (APA Accredited) Dissertation: Mixed-methods exploratory analysis of pica in pediatric sickle cell disease. Supervisor: Lindsey L. Cohen, Ph.D. August 2013- Master of Arts, Clinical Psychology May 2016 Georgia State University Atlanta, Georgia (APA Accredited) Thesis: Pediatric chronic abdominal pain nursing: A mixed method analysis of burnout Supervisor: Lindsey L. Cohen, Ph.D. May 2011 Bachelor of Science, Child Studies, Cognitive Studies Vanderbilt University Nashville, TN Honors Thesis: Easily Frustrated Infants: Implications for Emotion Regulation Strategies and Cognitive Functioning Chair: Julia Noland, Ph.D. Honors and Awards August 2016- Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA), Graduate Present Psychology Education Fellowship (Cohen, 2016-2019, GPE-HRSA, DHHS Grant 2 D40HP19643) Enhancing training of graduate students to work with disadvantaged populations: A pediatric psychology specialization March 2014 Bailey M. Wade Fellowship awarded to support an exceptional first- year psychology graduate student who demonstrated need, merit and goals with those manifested in the life of Dr. Bailey M. Wade. August 2013- Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA), Graduate July 2016 Psychology Education Fellowship (Cohen, 2010-2016, GPE-HRSA, DHHS Grant 1 D40HP1964301-00) Training