Southampton's Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gazetteer.Doc Revised from 10/03/02

Save No. 91 Printed 10/03/02 10:33 AM Gazetteer.doc Revised From 10/03/02 Gazetteer compiled by E J Wiseman Abbots Ann SU 3243 Bighton Lane Watercress Beds SU 5933 Abbotstone Down SU 5836 Bishop's Dyke SU 3405 Acres Down SU 2709 Bishopstoke SU 4619 Alice Holt Forest SU 8042 Bishops Sutton Watercress Beds SU 6031 Allbrook SU 4521 Bisterne SU 1400 Allington Lane Gravel Pit SU 4717 Bitterne (Southampton) SU 4413 Alresford Watercress Beds SU 5833 Bitterne Park (Southampton) SU 4414 Alresford Pond SU 5933 Black Bush SU 2515 Amberwood Inclosure SU 2013 Blackbushe Airfield SU 8059 Amery Farm Estate (Alton) SU 7240 Black Dam (Basingstoke) SU 6552 Ampfield SU 4023 Black Gutter Bottom SU 2016 Andover Airfield SU 3245 Blackmoor SU 7733 Anton valley SU 3740 Blackmoor Golf Course SU 7734 Arlebury Lake SU 5732 Black Point (Hayling Island) SZ 7599 Ashlett Creek SU 4603 Blashford Lakes SU 1507 Ashlett Mill Pond SU 4603 Blendworth SU 7113 Ashley Farm (Stockbridge) SU 3730 Bordon SU 8035 Ashley Manor (Stockbridge) SU 3830 Bossington SU 3331 Ashley Walk SU 2014 Botley Wood SU 5410 Ashley Warren SU 4956 Bourley Reservoir SU 8250 Ashmansworth SU 4157 Boveridge SU 0714 Ashurst SU 3310 Braishfield SU 3725 Ash Vale Gravel Pit SU 8853 Brambridge SU 4622 Avington SU 5332 Bramley Camp SU 6559 Avon Castle SU 1303 Bramshaw Wood SU 2516 Avon Causeway SZ 1497 Bramshill (Warren Heath) SU 7759 Avon Tyrrell SZ 1499 Bramshill Common SU 7562 Backley Plain SU 2106 Bramshill Police College Lake SU 7560 Baddesley Common SU 3921 Bramshill Rubbish Tip SU 7561 Badnam Creek (River -

{Download PDF} Portsmouth Pubs Ebook Free Download

PORTSMOUTH PUBS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Steve Wallis | 96 pages | 15 Feb 2017 | Amberley Publishing | 9781445659893 | English | Chalford, United Kingdom Portsmouth Pubs PDF Book Bristol, 10 pubs per square mile 4. Purnell Farm was then later renamed Middle Farm by the Goldsmith's. Third place is a tie between Bristol, Brighton and Hove, and Norwich, with all three spots having 10 pubs per square mile. St James' Hospital , an institution for the treatment of mental health, first opened in on what was then called Asylum Road, now named Locksway Road. More top stories. From Business: It's more than beer for us; MoMac is a place for the whole neighborhood to have fun. When looking at the UK as a whole, Portsmouth came out on top with almost double the number of pubs per square mile than London overall though many of the capital's boroughs soar far above Portsmouth's total. But it is Brighton and Hove that has the most pubs per people out of all three. Sarah Dinenage Con [9]. But researchers point out that the area is almost 12, square miles in size. Add your own AMAZing articles. Parking Available. Mostly consisting of makeshift houseboats, converted railway carriages and fisherman huts, many of these homes, lacking the basic amenities of electricity and plumbed water supplies, survived into the s until they were cleared. The land is still settling and the cavities of Milton Common make ideal homes for foxes and other wildlife. Trafalgar Arms 11 reviews. Stellar Wine Co. The taste is totally different from what I had and I was a frequent customer for the last years!!! The start of the week is your cue for free pool — you can take to the table free of charge all day on a Monday. -

Segar Stream River Itchen

Segar Stream River Itchen An advisory visit carried out by the Wild Trout Trust – January 2011 1 1. Introduction This report is the output of a Wild Trout Trust advisory visit undertaken on the Segar Stream which is a carrier of the River Itchen in Hampshire. The advisory visit was undertaken at the request of the Portsmouth Services Fly Fishing Club which has been invited to lease the fishing rights. Comments in this report are based on observations on the day of the site visit and discussions with Robin Bray, Anthony Kennett and Mark Kerr from the fishing club. Throughout the report, normal convention is followed with respect to bank identification i.e. banks are designated Left Bank (LB) or Right Bank (RB) whilst looking downstream. 2. Catchment overview The River Itchen is considered to be one of the finest examples of a chalk river in Europe and one of the most famous brown trout (Salmo trutta) fisheries in the world. The river is designated as Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) (Appendix 1). The Itchen rises from the chalk aquifer to the east of Winchester where groundwater fed springs feed into three headwater streams; the Alre, the Candover and the Tichbourne, or Cheriton Stream. The streams converge near Alresford and flow south west, through the centre of Winchester and on to join the sea in Southampton. The river is characterised by a plethora of man-made channels, some dug to provide milling power, some to support the old Itchen Navigation canal and others to feed the network of water meadow carriers. -

Hampshire Salmon Seminar 5Th October 1993 Contents

k *• 106 ; HAMPSHIRE SALMON SEMINAR 5TH OCTOBER 1993 CONTENTS PAGES 1-4 Chairman’s Introduction Arthur Humbert, Chairman Fisheries Advisory Committee 5-9 Introduction by Robin Crawshaw, Hampshire Area Fisheries Manager, NRA Southern Region 10-15 Introduction by Mick Lunn, Test & Itchen Association 16-22 Spawning Success Alisdair Scott, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food 23-28 Questions 29-33 What is the NRA doing? Lawrence Talks, Hampshire Area Fisheries Officer, NRA Southern Region 34-38 Questions 39-51 Migrating to Sea Ian Russell, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food 52-60 Questions 61-66 Returning from the Sea and Movement up River Adrian Fewings, Fisheries Scientist, NRA Southern Region 67-75 Summary Dr Tony Owen, Regional Fisheries Manager, NRA Southern Region 76-97 Open Forum Chairman's Introduction ARTHUR HUMBERT Chairman Fisheries Advisory Committee 1 NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY HAMPSHIRE SALMON SEMINAR - 5TH OCTOBER. 1993 Chairman’s Introduction: Arthur Humbert, Chairman Fisheries Advisory Committee Well, good evening ladies and gentlemen, as your Chairman it's my pleasure to address you briefly, and then to hand over to speakers. It will seem there is a programme in this book and it tells you when the questions may be asked. Now there's an old saying that you shouldn't believe all that you read in the press and I've been reading and hearing gloomy things about that.... I see words like "extinction” and "disappearance". Well that is past history. There was a danger of that years ago but the NRA has tackled the problem and we are now in an improving situation. -

Post-Medieval & Modern Berkshire & Hampshire

POST MEDIEVAL AND MODERN (INDUSTRIAL, MILITARY, INSTITUTIONS AND DESIGNED LANDSCAPES) HAMPSHIRE AND BERKSHIRE David Hopkins November 2006 Introduction Hampshire. Hampshire is dominated by the chalk landscape which runs in a broad belt, east west, across the middle of the county. The northern edge runs through Pilot Hill and Basingstoke, the southern edge through Kings Somborne and Horndean. These are large, open and fertile landscapes dominated by agriculture. Agriculture is the principle force behind the character of the landscape and the evolution of the transport network and such industry as exists. There are large vistas, with nucleated villages, isolated farms and large extents of formal enclosure. Market towns developed linked by transport routes. Small scale processing using the water power available from streams was supported by, and eventually replaced by, growing industrialisation in some towns, usually those where modern transport (such as rail) allowed development. These towns expanded and changed in character, whilst other less well placed towns continue to retain their market town character. North and south of the chalk are bands of tertiary deposits, sands, gravels and clays. Less fertile and less easy to farm for much of their history they have been dominated by Royal Forest. Their release from forest and small scale nature of the agricultural development has lead to a medieval landscape, with dispersed settlement and common edge settlement with frequent small scale isolated farms. The geology does provide opportunities for extractive industry, and the cheapness of the land, and in the north the proximity to London, led to the establishment of military training areas, and parks and gardens developed by London’s new wealthy classes. -

Line Guide Elegant Facade Has Grade II Listed Building Status

Stations along the route Now a Grade II listed The original Southern Railway built a wonderful Art Deco Now Grade II listed, the main Eastleigh Station the south coast port night and day, every day, for weeks on b u i l d i n g , R o m s e y style south-side entrance. Parts of the original building still building is set well back from the opened in 1841 named end. Station* opened in platforms because it was intended remain, as does a redundant 1930’s signal box at the west ‘Bishopstoke Junction’. Shawford is now a busy commuter station but is also an T h e o r i g i n a l G r e a t 1847, and is a twin of to place two additional tracks end of the station. In 1889 it became access point for walkers visiting Shawford Down. W e s t e r n R a i l w a y ’ s Micheldever station. through the station. However the ‘ B i s h o p s t o k e a n d terminus station called The booking hall once had a huge notice board showing The station had a small goods yard that closed to railway The famous children’s extra lines never appeared! Eastleigh’ and in 1923 ‘Salisbury (Fisherton)’ passengers the position of all the ships in the docks, and had use in 1960, but the site remained the location of a civil author, the Reverend The construction of a large, ramped i t b e c a m e s i m p l y was built by Isambard the wording ‘The Gateway of the World’ proudly mounted engineering contractor’s yard for many years. -

Area 3: Lower Itchen Valley Floodplain

Landscape Character Area - Area 3 Area 3: Lower Itchen Valley Floodplain Eastleigh Southampton Airport River Itchen R a ilw ay Itchen Valley Country Park M27 Scale "Imagery copyright Digital Millennium 0 125 250 375 500 625 m Map Partnership 2006" 56 Landscape Character Assessment for Eastleigh Borough Landscape Character Area - Area 3 Description 4.38 This is a landscape of flat grassland in former flood meadows that is now used predominantly to graze cattle. The open views are punctuated by tree belts and occasional small copses found alongside the ditches and streams. 4.39 At the southern end of the character area, the elevated M27 cuts through at the edge. To the west lies Southampton Airport. The sight and sound of the motorway traffic and airport aircraft dominate the character. The elevated railway cuts through the northern edge. The southern edge of the boundary roughly conforms to the boundary of the special area of conservation. 4.40 A large section of this area is occupied by the Itchen Valley Country Park which runs up to the railway embankment in north. The park is made up of water meadows associated with the River Itchen, woodland and meadows. The river meanders through the centre of the park with a network of small streams diffusing out. The Itchen Navigation runs through the area to the west of the river. The floodplain is so wide that there is virtually no sense of being in a valley, except at the area’s eastern edge. A more dominant characteristic is the great visual interest provided in foreground views by wetland vegetation, the river itself and the earthworks of the former flood meadows. -

River Itchen Status: Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)

County: Hampshire Site Name: River Itchen Status: Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) notified under Section 28 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. Environment Agency Region: Southern Water Company: Southern Water plc, Portsmouth Water plc Local Planning Authorities: Hampshire County Council; Winchester City Council; Eastleigh Borough Council; Southampton City Council. National Grid References: SU 589274, SU 563353 & SU 599324 to SU 439153 Length of River SSSI: Approx. 42 km Ordnance Survey Sheets: (1:50 000) 185 & 196 Area: 748.02 ha Date notified (under 1981 Act and 1991 Acts): Itchen Valley (Winnall Moors): 29 June 1984 Itchen Valley (Winchester Meadows): 29 June 1984 Itchen Valley (Cheriton to Kingsworthy): 29 June 1984 River Itchen: 17 July 1996 River Itchen further notification: 16 August 2000 Date confirmed: 25 April 2001 Reasons for Notification This site is notified for classic chalk stream and river, fen meadow, flood pasture and swamp habitats, particularly formations of in-channel vegetation dominated by water crowfoot Ranunculus spp, riparian vegetation communities (including wet woodlands) and side channels, runnels and ditches associated with the main river and former water meadows. The site is also notified for significant populations of the nationally-rare southern damselfly Coenagrion mercuriale and assemblages of nationally-rare and scarce freshwater and riparian invertebrates, including the white-clawed crayfish Austropotamobius pallipes. This site is notified for otter Lutra lutra, water vole Arvicola terrestris, freshwater fishes including bullhead Cottius gobbo, brook lamprey Lampetra planeri and Atlantic salmon Salmo salar, and the assemblage of breeding birds including tufted duck Aythya fuligula, pochard A. ferina and shoveler Anas clypeata, the waders lapwing Vanellus vanellus, redshank Tringa totanus and snipe Gallinago gallinago, and wetland passerines including sedge warbler Acrocephalus schoenobaenus, reed warbler A. -

Guidance on the Application Process and on Completing This Application Form Is Available at from the Solent LTB Website

V-8 Guidance on the application process and on completing this application form is available at from the Solent LTB website. One application should be completed per project. Applications are restricted to a maximum of 20 pages (excluding accompanying documentation). Please amend the sizes of the response boxes to suit your application. Accompanying Documentation Accompanying documentation should be restricted to: Letters of support from stakeholders; Map(s); and Scheme drawing(s). Deadline for applications Applications must be submitted to the Solent LTB by 1800 on Wednesday 12th June 2013. Please submit electronic versions of this form along with any accompanying documentation to: [email protected]. Where email attachments sum to 10mb or above in file size, you should ensure that arrangements are made for these to be received by the LTB by the above deadline. Please note, your Project Application Forms will be published on the Solent LTB website. Section A: Applicant Information A1 Lead applicant name (Organisation) Portsmouth City Council. A2 Joint applicant name(s) if applicable Not applicable. A3 Lead applicant address Civic Offices, Guildhall Square, Portsmouth, PO1 2BG. A4 Bid manager details Name: Simon Moon Position: Head of Transport & Environment Employer: Portsmouth City Council Telephone: 023 9283 4092 Email: [email protected] Section B: Eligibility Check List B1 Is the project included within the Transport Delivery Plan (TDP)? Yes No B2 Is the project expected to have a clearly defined scope? Yes -

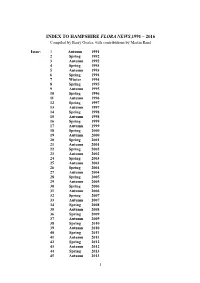

INDEX to HAMPSHIRE FLORA NEWS,1991 – 2016 Compiled by Barry Goater, with Contributions by Martin Rand

INDEX TO HAMPSHIRE FLORA NEWS,1991 – 2016 Compiled by Barry Goater, with contributions by Martin Rand Issue: 1 Autumn 1991 2 Spring 1992 3 Autumn 1992 4 Spring 1993 5 Autumn 1993 6 Spring 1994 7 Winter 1994 8 Spring 1995 9 Autumn 1995 10 Spring 1996 11 Autumn 1996 12 Spring 1997 13 Autumn 1997 14 Spring 1998 15 Autumn 1998 16 Spring 1999 17 Autumn 1999 18 Spring 2000 19 Autumn 2000 20 Spring 2001 21 Autumn 2001 22 Spring 2002 23 Autumn 2002 24 Spring 2003 25 Autumn 2003 26 Spring 2004 27 Autumn 2004 28 Spring 2005 29 Autumn 2005 30 Spring 2006 31 Autumn 2006 32 Spring 2007 33 Autumn 2007 34 Spring 2008 35 Autumn 2008 36 Spring 2009 37 Autumn 2009 38 Spring 2010 39 Autumn 2010 40 Spring 2011 41 Autumn 2011 42 Spring 2012 43 Autumn 2012 44 Spring 2013 45 Autumn 2013 1 46 Spring 2014 47 Autumn 2014 48 Spring 2015 49 Autumn 2015 50 Spring 2016 2 A Abbotts Ann [Abbotts Ann], SU3245.......................................................21:10,22:1,12,24:12,26:12,13, ................................27:7,9,28:15,16,18,31:18,19,32:19,21,22,38:19,44:25,26,44:27,45:14,46:33 Balksbury Hill, SU349444..........................................................................................................32:21 Cattle Lane, SU333438...........................................................................................31:18,44:27,45:16 Duck Street, SU3243.....................................................................................21:10,28:15,29:18,31:19 Hook Lane track, SU307433.......................................................................................................46:33 -

Soil Walk: St Catherine’S Hill, Winchester, Hampshire

® www.Soil-Net.com Soil Walk: St Catherine’s Hill, Winchester, Hampshire What is a soil walk Soil is one of the most wonderful things in nature This precious material that is under our feet wherever we walk enables our food to be grown, our wonderfully diverse flowers and trees to grow, our buildings, roads and railways to be supported, and is the home of billions of different organisms. Soil is amazing. There are an astonishing number of different soils - over 700 in the United Kingdom. In each landscape there will be several different soils. Walking through a particular landscape near your school or your home is the best way to discover interesting things about your local soils. Come and take part in this Soil-Net Soil Walk and see for yourself your local soils, how they differ from each other, and what the soils are being used for. The Soil Route This route will take you from the clayey soils of the Itchen river valley up into the chalk landscape of the Hampshire Wolds Not only is it a lovely scenic route but is also an area of outstanding archaeological importance. The Walk is circular, up and over St Catherine's Hill and back to the car park along the disused Itchen Navigation Canal, past St Cross hospital and the water meadows. The Mizmaze Travelling there and starting off Start at OS reference SU 484 280 [OS Explorer Map 132], and use the carpark beside Tun Bridge in Garnier Road, Winchester. This is easily accessed from the M3 at Junction 10. -

Tudors Beyond in Beautiful Countryside Near the Famous River Test

Further inland, Mottisfont Abbey stands Basingstoke Basing House The Tudors beyond in beautiful countryside near the famous River Test. Originally a 12th-century Winchester priory, it was made into a private house Andover TUDORS after Henry VIII’s split with the Catholic Farnham Explore Winchester’s Tudor history and Journey out of Winchester a few miles and you will find Church. Tel:01794 340757. A303 these interesting places with Tudor connections. Alton test your knowledge of the period At Southwick, you can see the church of Before her wedding, Mary travelled to Winchester from St James. Rebuilt in 1566 by John Whyte A34 M3 London, staying with Bishop Gardiner at his castle in A33 (a servant of the Earl of Southampton), Alresford A31 Farnham and then on to his palace at Bishop’s Waltham . WincWinchester A3 it is a rare example of a post- This medieval palace stood in a 10,000-acre park and had Mottisfont been a favourite hunting spot for Henry VIII. Bishops Reformation Tudor church and well A272 occupied the palace until the early 17th-century when it worth a visit. The interesting thing Petersfield Romsey was destroyed during the Civil War. The extensive ruins are about the church is its date. At a time worth a visit today, and events are sometime staged there. when churches were either being torn down, or their decoration removed, here M27 Tel: 01962 840500. Bishop's A3 is a church that was newly built. It is Waltham Old Basing House , home of the Lord Treasurer, William A31 especially noteworthy for its three- Southampton Wickham Paulet, was a huge castle, converted in Tudor times into a Southwick decker pulpit, its gallery, reredos (screen M27 Parish Church large private house.