When Culture and Biology Collide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senate and House of Rep- but 6,000 Miles Away, the Brave People Them

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 149 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2003 No. 125 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. minute and to revise and extend his re- minute and to revise and extend his re- The Chaplain, the Reverend Daniel P. marks.) marks.) Coughlin, offered the following prayer: Mr. BLUNT. Mr. Speaker, we come Mr. HOYER. Mr. Speaker, the gen- Two years have passed, but we have here today to remember the tragedy of tleman from Missouri (Mr. BLUNT) is not forgotten. America will never for- 2 years ago and remember the changes my counterpart in this House. It is his get the evil attack on September 11, that it has made in our country. responsibility to organize his party to 2001. But let us not be overwhelmed by Two years ago this morning, early in vote on issues of importance to this repeated TV images that bring back the morning, a beautiful day, much country and to express their views. paralyzing fear and make us vulnerable like today, we were at the end of a fair- And on my side of the aisle, it is my re- once again. Instead, in a moment of si- ly long period of time in this country sponsibility to organize my party to lence, let us stand tall and be one with when there was a sense that there real- express our views. At times, that is ex- the thousands of faces lost in the dust; ly was no role that only the Federal traordinarily contentious and we dem- let us hold in our minds those who still Government could perform, that many onstrate to the American public, and moan over the hole in their lives. -

Autumn in Brooklyn

AUTUMN IN BROOKLYN September-November 1978 AUTUMN IN BROOKLYN September-November 1978 RICHARD GRAYSON Superstition Mountain Press Phoenix – 2009 Copyright © 2009 by Richard Grayson. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Superstition Mountain Press 4303 Cactus Road Phoenix, AZ 85032 First Edition ISBN 978-0-578-03208-5 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Louis Strick Richard Grayson 1 Autumn in Brooklyn: September – November 1978 Monday, September 4, 1978 8 PM. I feel rather sad about the summer ending. It seems impossible that three months has passed since my birthday. I’ve always thought of the new year as beginning now rather than in January, and I still feel that way (even though this year’s Rosh Hashona is a month away). It’s chilly out now and today was sunny but just a bit too cool for swimming. I spent the afternoon with Josh – we drove around, played pinball at Buddy’s, chatted in the backyard. He’s just as sour on life as he always was; maybe he’s even worse. He and Simon went to the Eighth Street Bookshop to get an ABC to Literary Magazines by R.C. Morse, which I told him about. He said he saw Alice there, rummaging through magazines looking for a story by me. Laura mentioned staying with Peter Spielberg on the Cape, and Josh and Simon made the mistake of putting Peter down in front of her; she cooled considerably after hearing their comments. Josh and his friend Fat Ronnie want to start a literary magazine called Moron; the name expresses their general philosophy. -

Message to the Congress Transmitting Reports of The

1618 Nov. 8 / Administration of George W. Bush, 2001 those who travel abroad for business or vaca- ments have been acts of courage for which tion can all be ambassadors of American val- no one could have ever prepared. ues. Ours is a great story, and we must tell We will always remember the words of it, through our words and through our deeds. that brave man, expressing the spirit of a I came to Atlanta today to talk about an great country. We will never forget all we all-important question: How should we live have lost and all we are fighting for. Ours in the light of what has happened? We all is the cause of freedom. We’ve defeated free- have new responsibilities. dom enemies before, and we will defeat Our Government has a responsibility to them again. hunt down our enemies, and we will. Our We cannot know every turn this battle will Government has a responsibility to put need- take. Yet we know our cause is just and our less partisanship behind us and meet new ultimate victory is assured. We will, no doubt, challenges: better security for our people, face new challenges. But we have our march- and help for those who have lost jobs and ing orders: My fellow Americans, ‘‘Let’s roll.’’ livelihoods in the attacks that claimed so NOTE: The President spoke at 8:03 p.m. at the many lives. I made some proposals to stimu- World Congress Center. In his address, he re- late economic growth which will create new ferred to Kathy Nguyen, a New York City hospital jobs and make America less dependent on worker who died October 31 of inhalation anthrax; foreign oil. -

Brooklyn College Magazine, Spring 2013, Volume 2

BROOKLYN COLLEGE MAGAZINE | SPRING 2013 1 B Brooklyn College Magazine Volume 2 | Number 2 | Spring 2013 Brooklyn College Editor-in-Chief Art Director Advisory Committee 2900 Bedford Avenue Keisha-Gaye Anderson Lisa Panazzolo Nicole Hosten-Haas, Chief of Staff to the President Brooklyn, NY 11210-2889 Steven Schechter, Managing Editor Production Assistant Executive Director of Government and External Affairs [email protected] Audrey Peterson Mammen P. Thomas Ron Schweiger ’70, President of the Brooklyn College Alumni Association © 2013 Brooklyn College Andrew Sillen ’74, Vice President for Institutional Advancement Staff Writers Staff Photographers Jeremy A. Thompson, Executive Director of Marketing, Communications, Ernesto Mora David Rozenblyum President and Public Relations Richard Sheridan Craig Stokle Karen L. Gould Colette Wagner, Assistant Provost for Planning and Special Projects Jamilah Simmons Editorial Assistants Provost Contributing Writers Dominique Carson ‘12 William A. Tramontano James Anderson Mark Zhuravsky ‘10 Matt Fleischer-Black Joe Fodor Katti Gray Alex Lang Anthony Ramos Julie Revelant Ron Schweiger ’70 On the Scene Award-winning alumni and a new graduate school of cinema in the works make Brooklyn College a 9 prime destination for the next generation of entertainment industry game changers. Forward Momentum Leading-edge scientific research at Brooklyn College continues to 14 attract national attention, as well as prestigious awards. The Brooklyn Connection Alumni mentors with top-flight careers and talented business students form 20 professional and personal bonds that endure well past graduation. 2 From the President’s Desk 3 Snapshots 5 Notables 7 Features He’s not an 23 College News alumnus, so why is Kevin 27 Career Corner Bacon in our 28 Athletics magazine? 30 Alumni Profile Turn to page 31 Class Notes ten to find out. -

Download Winter 2008

Why churches don’t disciple, and how yours can 48 Enriching and equipping Spirit-filled ministers Winter 2008 DISCIPLESHIP The neglected mandate Ministry Matters / GARY R. ALLEN hristians have already said everything deal about the church. The bylaws describe that could possibly be said about how we command and control the church, but discipleship. Yet, there is a significant the bylaws give little information concerning gap between the number of people how we are to release people to reach their our churches report as being saved and neighbors. Often the checkbook reveals that the number that indicates increased we spend a great deal of money operating and attendance in these churches. We maintaining the church, but spend little to are winning people to Christ, but we are not reach our community. We would do well to teaching, training, and retaining them. spend more on materials and methods that We are emphasizing discipleship because: reach new people. It Is a Mandate From Our Lord We Need To Continually Improve Our “Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, Materials and Methods baptizing them in the name of the Father and The Word of God never changes. Our mission of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching never changes. But the context and methods of them to obey everything I have commanded our ministry may change. If we are presently you. And surely I am with you always, to the using materials and methods that once reached Changing our very end of the age” (Matthew 28:19,20). Times a previous generation, we may need to evaluate have changed, people have changed, cultures what we are doing to ensure we are effectively purpose have changed, but this urgent mandate from reaching today’s generation. -

CCMA Coleman Competition (1947-2015)

THE COLEMAN COMPETITION The Coleman Board of Directors on April 8, 1946 approved a Los Angeles City College. Three winning groups performed at motion from the executive committee that Coleman should launch the Winners Concert. Alice Coleman Batchelder served as one of a contest for young ensemble players “for the purpose of fostering the judges of the inaugural competition, and wrote in the program: interest in chamber music playing among the young musicians of “The results of our first chamber music Southern California.” Mrs. William Arthur Clark, the chair of the competition have so far exceeded our most inaugural competition, noted that “So far as we are aware, this is sanguine plans that there seems little doubt the first effort that has been made in this country to stimulate, that we will make it an annual event each through public competition, small ensemble chamber music season. When we think that over fifty performance by young people.” players participated in the competition, that Notices for the First Annual Chamber Music Competition went out the groups to which they belonged came to local newspapers in October, announcing that it would be held from widely scattered areas of Southern in Culbertson Hall on the Caltech campus on April 19, 1947. A California and that each ensemble Winners Concert would take place on May 11 at the Pasadena participating gave untold hours to rehearsal Playhouse as part of Pasadena’s Twelfth Annual Spring Music we realize what a wonderful stimulus to Festival sponsored by the Civic Music Association, the Board of chamber music performance and interest it Education, and the Pasadena City Board of Directors. -

Catalyst Growing Funds for Parkinson’S Research

The Parkinson Alliance Summer/Fall 2002 Catalyst Growing Funds for Parkinson’s Research Udall Centers Getting it Together INSIDE by, Ken Aidekman Message from the President . 2 n the process of funding research curing Parkinson’s would require a level Message from the Ithere exists a natural give and take of organization imposed upon scientists Executive Director . 4 between the pursuit of pure science from outside the scientific commu- Team Parkinson Going National . 5 and the effort to accomplish treatment- nity. It may seem like common sense Barry Green Takes on Medicare oriented goals. Fundamental curios- that cooperation and sharing among and Makes a Difference . 5 ity and the desire to contribute to a scientists will speed us toward a cure, American Legion Raises growing body of knowledge motivate but it is by no means proven and it still $51,000 for the Alliance . 5 scientists. A large part of their time is requires a certain amount of creative Alliance donates to The Todd M. spent fashioning studies that have suf- thinking to successfully implement. Beamer Foundation . 5 ficient scientific merit to be funded and The Morris K. Udall Act stipulates Past Events . 6-7 then, once funded, carrying out the that “The Secretary (of the NIH) shall Upcoming Events . 8 experiments that will prove or disprove provide for the establishment of 10 their hypothesis. With a lot of hard Parkinson’s Research Centers. (In fact, of Excellence for Parkinson’s Disease work and a bit of luck the results of there are 11 centers.) Such centers shall Research. 2002 was the first year in their labors will be published in jour- … coordinate research with other such which NINDS invited laypersons from nals and add to our understanding of Centers and related public and private the Parkinson’s community to observe neuroscience. -

Academy of the Sacred Heart

MATER’S NEW PLACE OF HONOR • INNOVATIVE APPROACH TO SCIENCE • ALUMNAE NEWS • RECENT AWARDS AND MORE the ACADEMY OF THE SACRED HEART AUTUMN 2011 VOL. 5 NO. 2 thE The Academy of the Sacred Heart invites you to The Liturgy and Dedication of the Arts and Athletics Complex on the Feast of Mater Admirabilis Celebrant: Archbishop Gregory M. Aymond, D.D. Thursday, October 20, 2011 | 8:30 am Arts and Athletics Complex 4500 block of Carondelet Street TOURS FOLLOWING LITURGY Spirit Night District Volleyball Game & Tours | 5:30 pm MESSAGE FROM THE HEADMASTER schools would like some of the art treasures In addition to telling the story of our Mater from Kenwood. I wrote and asked for the painting, I invite our readers to enjoy coverage portrait of Mater Admirabilis that RSCJ of Commencement for the Class of 2011 and from several generations remember as being the Eighth Grade Closing Exercises for the at the end of a long corridor at the Kenwood class of 2015. We also feature profiles on recent novitiate. This is the portrait featured on the alumnae—the artist whose work is featured on cover of this issue of The Bridge. The painting the front of this magazine, entrepreneurial sisters arrived in New Orleans this past spring. whose yogurt has taken the city by storm, and As this seven-foot tall painting stood in two alumnae who are forging careers in television my office waiting to be placed, I wondered if and media. With the multi-media studio in our it would be possible to replicate the artwork new arts complex on the Rosary’s back square, surrounding the original fresco of Mater in Sacred Heart girls will have opportunities to Rome. -

Gaycalgary and Edmonton Magazine #72, October 2009 Table of Contents Table of Contents

October 2009 ISSUE 72 The Only Magazine Dedicated to Alberta’s GLBT+ Community FREE ALBERTA’s top TEN GLBT FIGURES Part 2 THE PRICE OF OUR HARD-WON RIGHTS THE POLICE SERVICE Are GLBT Trust Issues Unfounded? COMMUNITY DIRECTORY • MAP AND EVENTS • TOURISM INFO >> STARTING ON PAGE 17 GLBT RESOURce • CALGARy • EDMONTon • ALBERTA www.gaycalgary.com GayCalgary and Edmonton Magazine #7, October 009 Table of Contents Table of Contents Publisher: ................................Steve Polyak 5 Homowners Editor: ...............................Rob Diaz-Marino Publisher’s Column Graphic Design: ................Rob Diaz-Marino Sales: .......................................Steve Polyak 8 A Visit to Folsom Street Fair Writers and Contributors Mercedes Allen, Chris Azzopardi, Dallas 9 Apollo & Team Edmonton Curling Barnes, Antonio Bavaro , Camper British, “Chess on Ice” Returns for Another Season 8 Dave Brousseau, Sam Casselman, Jason Clevett, Andrew Collins, James S.M. Demers, Rob Diaz-Marino, Jack Fertig, AGE Glen Hanson, Joan Hilty, Evan Kayne, 11 The Police Service P Boy David, Richard Labonte, Stephen Are GLBT Trust Issues Unfounded? Lock, Allan Neuwirth, Steven Petrow, Steve Polyak, Pam Rocker, Romeo San Vicente, Diane Silver, D’Anne Witkowski, Dan Woog, 13 Chelsea Boys and the GLBT Community of Calgary, Edmonton, and Alberta. 14 Out of Town Palm Springs, California Photography Steve Polyak, Rob Diaz-Marino and Jason Clevett. 17 Directory and Events Videography Steve Polyak, Rob Diaz-Marino 23 Letters to the Editor 11 Printers 24 It’s About Pride...And -

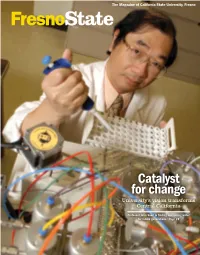

Catalyst for Change University’S Vision Transforms Central California

The Magazine of California State University, Fresno Catalyst for change University’s vision transforms Central California Professor John Suen is finding and saving water for future generations. Page 28 FresnoState Magazine is published twice annually by the Office of University Communications at California State University, Fresno. Spring 2007 President John D. Welty Vice President of University Advancement Peter N. Smits Associate Vice President for University Communications Mark Aydelotte Director of News Services/Magazine Editorial Direction Shirley Melikian Armbruster FresnoState Magazine Editor Lanny Larson Director of Publications and New Media Bruce Whitworth Graphic Design Consultant Pam Chastain Alumni Editor Sarah Woodward campus notes 4 University Communications Editorial Team Margarita Adona, Esther Gonzalez, Todd Graves, The buzz is about bees and building, crime-solving and Priscilla Helling, Angel Langridge, Kevin Medeiros, culture, teaching and time. April Schulthies, Tom Uribes Student Assistants Megan Jacobsen, Brianna Simpson, Andrea Vega campus news 6 Global connections to education, exercise, water The opinions expressed in this magazine do not necessarily reflect official university policy. Letters to the editor and contributions to development and conservation and enhanced the Class Notes section are welcome; they may be edited for clarity farmland use share the spotlight with campus initiatives and length. Unless otherwise noted, articles may be reprinted as on athletics finances and cultural heritage. long as credit is given. Copyrighted photos may not be reprinted without express written consent of the photographer. Clippings and other editorial contributions are appreciated. All inquiries and comments, including requests for faculty contact information, giving news 10 21 should be sent to Editor, FresnoState Magazine, 5241 N. -

ARIZONA CATHOLIC CONFERENCE Diocese of Gallup H Diocese of Phoenix H Diocese of Tucson Holy Protection of Mary Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Phoenix

ARIZONA CATHOLIC CONFERENCE Diocese of Gallup H Diocese of Phoenix H Diocese of Tucson Holy Protection of Mary Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Phoenix H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H he Arizona Catholic Conference (ACC) does not endorse candidates or indicate our www.azredistricting.org/districtlocator. is the public policy arm of the Diocese support or opposition to the questions. All candidates in the aforementioned races Tof Phoenix, the Diocese of Tucson, the Included in the ACC Voters Guide are were sent a survey and asked to respond with Diocese of Gallup, and the Holy Protection of races covering the U.S. Senate, U.S. House of whether they Support (S) or Oppose (O) Mary Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Phoenix. Representatives, Corporation Commission, the given statements. The ACC Voters Guide The ACC is a non-partisan entity and does State Senate and State House. It is important lists every one of these candidates regardless not endorse any candidates. to remember that members of the State of whether they returned a survey. Many The ACC Voters Guide is meant solely Senate and State House are elected by candidates elaborated on their responses, to provide an important educational tool legislative district. Each legislative district indicated by an asterisk, which can be found containing unbiased information on the includes one State Senator and two State online at www.azcatholicconference.org along upcoming elections. Pursuant to Internal Representatives. -

Dr. David Geier the Injuries That Changed Sports Forever

The Injuries That Changed Sports Forever dr. david geier Dr. David Geier That’s Gotta Hurt The Injuries That Changed Sports Forever ForeEdge Uncorrected Page Proof copyrighted material Geier_1stpgs.indd 3 2/7/17 12:27 PM ForeEdge An imprint of University Press of New England www.upne.com © 2017 Dr. David Geier All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Minion Pro For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Suite 250, Lebanon NH 03766; or visit www.upne.com <<CIP data TK>> 5 4 3 2 1 Uncorrected Page Proof copyrighted material Geier_1stpgs.indd 4 2/7/17 12:27 PM Introduction March 7, 1970 “I realized that something was wrong,” Bogataj would recall years later to Phil- adelphia Daily News columnist Rich Hofman. “I tried not to go, tried to stop myself. But the speed was too big, about 105 kilometers an hour [roughly 65 miles per hour]. So I did everything I was able to do.” You might not know the name Vinko Bogataj, but you know who he is—or at least you know his crash. Earlier that day, Bogataj had lef the chain factory in Yugoslavia where he worked, along with his three friends, to drive to Oberstdorf, West Germany. Growing up on a farm in a family with eight children, the 22-year-old set out on that snowy day to compete in a passion of his: ski fying. Despite working full time, Bogataj was fairly accomplished in the sport that would later become known as ski jumping.