Arthritis by the Numbers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missing Pieces Report: the 2018 Board Diversity Census of Women

alliance for board diversity Missing Pieces Report: The 2018 Board Diversity Census of Women and Minorities on Fortune 500 Boards Missing Pieces Report: The 2018 Board Diversity Census of Women and Minorities on Fortune 500 Boards About the Alliance for Board Diversity Founded in 2004, the Alliance for Board Diversity (ABD) is a collaboration of four leadership organizations: Catalyst, The Executive Leadership Council (ELC), the Hispanic Association on Corporate Responsibility (HACR), and LEAP (Leadership Education for Asian Pacifics). Diversified Search, an executive search firm, is a founding partner of the alliance and serves as an advisor and facilitator. The ABD’s mission is to increase the representation of women and minorities on corporate boards. More information about ABD is available at www.theabd.org. About Deloitte In the US, Deloitte LLP and Deloitte USA LLP are member firms of DTTL. The subsidiaries of Deloitte LLP provide industry- leading audit & assurance, consulting, tax, and risk and financial advisory services to many of the world’s most admired brands, including more than 85 percent of the Fortune 500 and more than 6,000 private and middle market companies. Our people work across more than 20 industry sectors with one purpose: to deliver measurable, lasting results. We help reinforce public trust in our capital markets, inspire clients to make their most challenging business decisions with confidence, and help lead the way toward a stronger economy and a healthy society. As part of the DTTL network of member firms, we are proud to be associated with the largest global professional services network, serving our clients in the markets that are most important to them. -

Is Palindromic Rheumatism Amongst Children a Benign Disease? Yonatan Butbul-Aviel1,2,3, Yosef Uziel4,5, Nofar Hezkelo4, Riva Brik1,2,3,4 and Gil Amarilyo4,6*

Butbul-Aviel et al. Pediatric Rheumatology (2018) 16:12 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-018-0227-z RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Is palindromic rheumatism amongst children a benign disease? Yonatan Butbul-Aviel1,2,3, Yosef Uziel4,5, Nofar Hezkelo4, Riva Brik1,2,3,4 and Gil Amarilyo4,6* Abstract Background: Palindromic rheumatism is an idiopathic, periodic arthritis characterized by multiple, transient, recurring episodes. Palindromic rheumatism is well-characterized in adults, but has never been reported in pediatric populations. The aim of this study was to characterize the clinical features and outcomes of a series of pediatric patients with palindromic rheumatism. Methods: We defined clinical criteria for palindromic rheumatism and reviewed all clinical visits in three Pediatric Rheumatology centers in Israel from 2006through 2015, to identify patients with the disease. We collected retrospective clinical and laboratory data on patients who fulfilled the criteria, and reviewed their medical records in order to determine the proportion of patients who had developed juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Results: Overall, 10 patients were identified. Their mean age at diagnosis was 8.3 ± 4.5 years and the average follow-up was 3.8 ± 2.7 years. The mean duration of attacks was 12.2 ± 8.4 days. The most frequently involved joints were knees. Patients tested positive for rheumatoid factor in 20% of cases. One patient developed polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis after three years of follow-up, six patients (60%) continued to have attacks at their last follow-up and only three children (30%) achieved long-term remission. Conclusions: Progression to juvenile idiopathic arthritis is rare amongst children with palindromic rheumatism and most patients continued to have attacks at their last follow-up. -

Juvenile Spondyloarthropathies: Inflammation in Disguise

PP.qxd:06/15-2 Ped Perspectives 7/25/08 10:49 AM Page 2 APEDIATRIC Volume 17, Number 2 2008 Juvenile Spondyloarthropathieserspective Inflammation in DisguiseP by Evren Akin, M.D. The spondyloarthropathies are a group of inflammatory conditions that involve the spine (sacroiliitis and spondylitis), joints (asymmetric peripheral Case Study arthropathy) and tendons (enthesopathy). The clinical subsets of spondyloarthropathies constitute a wide spectrum, including: • Ankylosing spondylitis What does spondyloarthropathy • Psoriatic arthritis look like in a child? • Reactive arthritis • Inflammatory bowel disease associated with arthritis A 12-year-old boy is actively involved in sports. • Undifferentiated sacroiliitis When his right toe starts to hurt, overuse injury is Depending on the subtype, extra-articular manifestations might involve the eyes, thought to be the cause. The right toe eventually skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract and heart. The most commonly accepted swells up, and he is referred to a rheumatologist to classification criteria for spondyloarthropathies are from the European evaluate for possible gout. Over the next few Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG). See Table 1. weeks, his right knee begins hurting as well. At the rheumatologist’s office, arthritis of the right second The juvenile spondyloarthropathies — which are the focus of this article — toe and the right knee is noted. Family history is might be defined as any spondyloarthropathy subtype that is diagnosed before remarkable for back stiffness in the father, which is age 17. It should be noted, however, that adult and juvenile spondyloar- reported as “due to sports participation.” thropathies exist on a continuum. In other words, many children diagnosed with a type of juvenile spondyloarthropathy will eventually fulfill criteria for Antinuclear antibody (ANA) and rheumatoid factor adult spondyloarthropathy. -

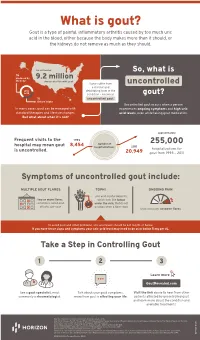

Uncontrolled Gout Fact Sheet

What is gout? Gout is a type of painful, inflammatory arthritis caused by too much uric acid in the blood, either because the body makes more than it should, or the kidneys do not remove as much as they should. An estimated So, what is ⅔ produced by 9.2 million the body Americans live with gout Some suffer from uncontrolled a chronic and uric debilitating form of the acid condition – known as gout? ⅓ uncontrolled gout. dietary intake Uncontrolled gout occurs when a person In many cases, gout can be managed with experiences ongoing symptoms and high uric standard therapies and lifestyle changes. acid levels, even while taking gout medication. But what about when it’s not? approximately Frequent visits to the 1993 number of 255,000 hospital may mean gout 8,454 hospitalizations 2011 is uncontrolled. hospitalizations for 20,949 gout from 1993 – 2011 Symptoms of uncontrolled gout include: MULTIPLE GOUT FLARES TOPHI ONGOING PAIN uric acid crystal deposits, two or more flares, which look like lumps sometimes called gout under the skin, that do not attacks, per year go away when a flare stops that continues between flares To avoid gout and other problems, uric acid levels should be 6.0 mg/dL or below. If you have these signs and symptoms your uric acid level may need to be at or below 5 mg per dL. Take a Step in Controlling Gout 1 2 3 Learn more GoutRevealed.com See a gout specialist, most Talk about your gout symptoms, Visit the link above to hear from other commonly a rheumatologist. -

Acute < 6 Weeks Subacute ~ 6 Weeks Chronic >

Pain Articular Non-articular Localized Generalized . Regional Pain Disorders . Myalgias without Weakness Soft Tissue Rheumatism (ex., fibromyalgia, polymyalgia (ex., soft tissue rheumatism rheumatica) tendonitis, tenosynovitis, bursitis, fasciitis) . Myalgia with Weakness (ex., Inflammatory muscle disease) Clinical Features of Arthritis Monoarthritis Oligoarthritis Polyarthritis (one joint) (two to five joints) (> five joints) Acute < 6 weeks Subacute ~ 6 weeks Chronic > 6 weeks Inflammatory Noninflammatory Differential Diagnosis of Arthritis Differential Diagnosis of Arthritis Acute Monarthritis Acute Polyarthritis Inflammatory Inflammatory . Infection . Viral - gonococcal (GC) - hepatitis - nonGC - parvovirus . Crystal deposition - HIV - gout . Rheumatic fever - calcium . GC - pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) . CTD (connective tissue diseases) - hydroxylapatite (HA) - RA . Spondyloarthropathies - systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) - reactive . Sarcoidosis - psoriatic . - inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Spondyloarthropathies - reactive - Reiters . - psoriatic Early RA - IBD - Reiters Non-inflammatory . Subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) . Trauma . Hemophilia Non-inflammatory . Avascular Necrosis . Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy . Internal derangement Chronic Monarthritis Chronic Polyarthritis Inflammatory Inflammatory . Chronic Infection . Bony erosions - fungal, - RA/Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA ) - tuberculosis (TB) - Crystal deposition . Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) - Infection (15%) - Erosive OA (rare) Non-inflammatory - Spondyloarthropathies -

Missing Pieces Report: the Board Diversity Census of Women And

Missing Pieces Report: The Board Diversity Census of Women and Minorities on Fortune 500 Boards, 6th edition Missing Pieces Report: The Board Diversity Census of Women and Minorities on Fortune 500 Boards, 6th edition About the Alliance for Board Diversity Founded in 2004, the Alliance for Board Diversity (ABD) is a collaboration of four leadership organizations: Catalyst, the Executive Leadership Council (ELC), the Hispanic Association on Corporate Responsibility (HACR), and Leadership Education for Asian Pacifics (LEAP). Diversified Search Group, an executive search firm, is a founding partner of the alliance and serves as an advisor and facilitator. The ABD’s mission is to enhance shareholder value in Fortune 500 companies by promoting inclusion of women and minorities on corporate boards. More information about ABD is available at theabd.org. About Deloitte Deloitte provides industry-leading audit, consulting, tax and advisory services to many of the world’s most admired brands, including nearly 90% of the Fortune 500® and more than 7,000 private companies. Our people come together for the greater good and work across the industry sectors that drive and shape today’s marketplace — delivering measurable and lasting results that help reinforce public trust in our capital markets, inspire clients to see challenges as opportunities to transform and thrive, and help lead the way toward a stronger economy and a healthier society. Deloitte is proud to be part of the largest global professional services network serving our clients in the markets that are most important to them. Now celebrating 175 years of service, our network of member firms spans more than 150 countries and territories. -

Knee Osteoarthritis

Patrick O’Keefe, MD Knee Osteoarthritis Overview What is knee osteoarthritis? Osteoarthritis, also known as Osteoarthritis is the most common type of knee arthritis. "wear and tear" arthritis, is a common problem for many A healthy knee easily bends and straightens because of a people after they reach middle smooth, slippery tissue called articular cartilage. This age. Osteoarthritis of the knee substance covers, protects, and cushions the ends of the is a leading cause of disability leg bones that form your knee. in the United States. It develops slowly and the pain it Between your bones, two c-shaped pieces of meniscal causes worsens over time. cartilage act as "shock absorbers" to cushion your knee Although there is no cure for joint. Osteoarthritis causes cartilage to wear away. osteoarthritis, there are many treatment options available. How it happens: Osteoarthritis occurs over time. When the Using these, people with cartilage wears away, it becomes frayed and rough. Moving osteoarthritis are able to the bones along this exposed surface is painful. manage pain, stay active, and live fulfilling lives. If the cartilage wears away completely, it can result in bone rubbing on bone. To make up for the lost cartilage, Questions the damaged bones may start to grow outward and form painful spurs. If you have any concerns or questions after your surgery, Symptoms: Pain and stiffness are the most common during business hours call symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. Symptoms tend to be 763-441-0298 or Candice at worse in the morning or after a period of inactivity. 763-302-2613. -

Juvenile Arthritis and Exercise Therapy: Susan Basile

Mini Review iMedPub Journals Journal of Childhood & Developmental Disorders 2017 http://www.imedpub.com ISSN 2472-1786 Vol. 3 No. 2: 7 DOI: 10.4172/2472-1786.100045 Juvenile Arthritis and Exercise Therapy: Susan Basile Current Research and Future Considerations Department of Kinesiology and Health, Georgia State University, IL, USA Abstract Corresponding author: Susan Basile Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) is a chronic condition affecting significant numbers of children and young adults. Symptoms such as pain and swelling can [email protected] lead to secondary conditions such as altered movement patterns and decreases in physical activity, range of motion, aerobic capacity, and strength. Exercise therapy has been an increasingly utilized component of treatment which addresses both Department of Kinesiology and Health, primary and secondary symptoms. The objective of this paper was too give an Georgia State University, USA. overview of the current research on different types of exercise therapies, their measurements, and outcomes, as well as to make recommendations for future Tel: 630-583-1128 considerations and research. After defining the objective, articles involving patients with JIA and exercise or physical activity-based interventions were identified through electronic databases and bibliographic hand search of the Citation:Basile S. Juvenile Arthritis and existing literature. In all, nineteen articles were identified for inclusion. Studies Exercise Therapy: Current Research and involved patients affected by multiple subtypes of arthritis, mostly of lower body Future Considerations. J Child Dev Disord. joints. Interventions ranged from light systems of movement like Pilates to an 2017, 3:2. intense individualized neuromuscular training program. None of the studies exhibited notable negative effects beyond an individual level, and most produced positive outcomes, although the significance varied. -

Septic Arthritis of the Sternoclavicular Joint

J Am Board Fam Med: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.2012.06.110196 on 7 November 2012. Downloaded from BRIEF REPORT Septic Arthritis of the Sternoclavicular Joint Jason Womack, MD Septic arthritis is a medical emergency that requires immediate action to prevent significant morbidity and mortality. The sternoclavicular joint may have a more insidious onset than septic arthritis at other sites. A high index of suspicion and judicious use of laboratory and radiologic evaluation can help so- lidify this diagnosis. The sternoclavicular joint is likely to become infected in the immunocompromised patient or the patient who uses intravenous drugs, but sternoclavicular joint arthritis in the former is uncommon. This case series describes the course of 2 immunocompetent patients who were treated conservatively for septic arthritis of the sternoclavicular joint. (J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25: 908–912.) Keywords: Case Reports, Septic Arthritis, Sternoclavicular Joint Case 1 of admission, he continued to complain of left cla- A 50-year-old man presented to his primary care vicular pain, and the course of prednisone failed to physician with a 1-week history of nausea, vomit- provide any pain relief. The patient denied any ing, and diarrhea. His medical history was signifi- current fevers or chills. He was afebrile, and exam- cant for 1 episode of pseudo-gout. He had no ination revealed a swollen and tender left sterno- chronic medical illnesses. He was noted to have a clavicular (SC) joint. The prostate was normal in heart rate of 60 beats per minute and a blood size and texture and was not tender during palpa- pressure of 94/58 mm Hg. -

Adult Still's Disease

44 y/o male who reports severe knee pain with daily fevers and rash. High ESR, CRP add negative RF and ANA on labs. Edward Gillis, DO ? Adult Still’s Disease Frontal view of the hands shows severe radiocarpal and intercarpal joint space narrowing without significant bony productive changes. Joint space narrowing also present at the CMC, MCP and PIP joint spaces. Diffuse osteopenia is also evident. Spot views of the hands after Tc99m-MDP injection correlate with radiographs, showing significantly increased radiotracer uptake in the wrists, CMC, PIP, and to a lesser extent, the DIP joints bilaterally. Tc99m-MDP bone scan shows increased uptake in the right greater than left shoulders, as well as bilaterally symmetric increased radiotracer uptake in the elbows, hands, knees, ankles, and first MTP joints. Note the absence of radiotracer uptake in the hips. Patient had bilateral total hip arthroplasties. Not clearly evident are bilateral shoulder hemiarthroplasties. The increased periprosthetic uptake could signify prosthesis loosening. Adult Stills Disease Imaging Features • Radiographs – Distinctive pattern of diffuse radiocarpal, intercarpal, and carpometacarpal joint space narrowing without productive bony changes. Osseous ankylosis in the wrists common late in the disease. – Joint space narrowing is uniform – May see bony erosions. • Tc99m-MDP Bone Scan – Bilaterally symmetric increased uptake in the small and large joints of the axial and appendicular skeleton. Adult Still’s Disease General Features • Rare systemic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology • 75% have onset between 16 and 35 years • No gender, race, or ethnic predominance • Considered adult continuum of JIA • Triad of high spiking daily fevers with a skin rash and polyarthralgia • Prodromal sore throat is common • Negative RF and ANA Adult Still’s Disease General Features • Most commonly involved joint is the knee • Wrist involved in 74% of cases • In the hands, interphalangeal joints are more commonly affected than the MCP joints. -

Joint Pain Or Joint Disease

ARTHRITIS BY THE NUMBERS Book of Trusted Facts & Figures 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................4 Medical/Cost Burden .................................... 26 What the Numbers Mean – SECTION 1: GENERAL ARTHRITIS FACTS ....5 Craig’s Story: Words of Wisdom What is Arthritis? ...............................5 About Living With Gout & OA ........................ 27 Prevalence ................................................... 5 • Age and Gender ................................................................ 5 SECTION 4: • Change Over Time ............................................................ 7 • Factors to Consider ............................................................ 7 AUTOIMMUNE ARTHRITIS ..................28 Pain and Other Health Burdens ..................... 8 A Related Group of Employment Impact and Medical Cost Burden ... 9 Rheumatoid Diseases .........................28 New Research Contributes to Osteoporosis .....................................9 Understanding Why Someone Develops Autoimmune Disease ..................... 28 Who’s Affected? ........................................... 10 • Genetic and Epigenetic Implications ................................ 29 Prevalence ................................................... 10 • Microbiome Implications ................................................... 29 Health Burdens ............................................. 11 • Stress Implications .............................................................. 29 Economic Burdens ........................................ -

Approach to Polyarthritis for the Primary Care Physician

24 Osteopathic Family Physician (2018) 24 - 31 Osteopathic Family Physician | Volume 10, No. 5 | September / October, 2018 REVIEW ARTICLE Approach to Polyarthritis for the Primary Care Physician Arielle Freilich, DO, PGY2 & Helaine Larsen, DO Good Samaritan Hospital Medical Center, West Islip, New York KEYWORDS: Complaints of joint pain are commonly seen in clinical practice. Primary care physicians are frequently the frst practitioners to work up these complaints. Polyarthritis can be seen in a multitude of diseases. It Polyarthritis can be a challenging diagnostic process. In this article, we review the approach to diagnosing polyarthritis Synovitis joint pain in the primary care setting. Starting with history and physical, we outline the defning characteristics of various causes of arthralgia. We discuss the use of certain laboratory studies including Joint Pain sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibody, and rheumatoid factor. Aspiration of synovial fuid is often required for diagnosis, and we discuss the interpretation of possible results. Primary care physicians can Rheumatic Disease initiate the evaluation of polyarthralgia, and this article outlines a diagnostic approach. Rheumatology INTRODUCTION PATIENT HISTORY Polyarticular joint pain is a common complaint seen Although laboratory studies can shed much light on a possible diagnosis, a in primary care practices. The diferential diagnosis detailed history and physical examination remain crucial in the evaluation is extensive, thus making the diagnostic process of polyarticular symptoms. The vast diferential for polyarticular pain can difcult. A comprehensive history and physical exam be greatly narrowed using a thorough history. can help point towards the more likely etiology of the complaint. The physician must frst ensure that there are no symptoms pointing towards a more serious Emergencies diagnosis, which may require urgent management or During the initial evaluation, the physician must frst exclude any life- referral.