Sphragis-Epigrams Versus Role-Playing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry's Politics in Archaic Greek Epic and Lyric

Oral Tradition, 28/1 (2013): 143-166 Poetry’s Politics in Archaic Greek Epic and Lyric David F. Elmer In memoriam John Miles Foley1 The Iliad’s Politics of Consensus In a recent book (Elmer 2013) examining the representation of collective decision making in the Iliad, I have advanced two related claims: first, that the Iliad projects consensus as the ideal outcome of collective deliberation; and second, that the privileging of consensus can be meaningfully correlated with the nature of the poem as the product of an oral tradition.2 The Iliad’s politics, I argue, are best understood as a reflection of the dynamics of the tradition out of which the poem as we know it developed. In the course of the present essay, I intend to apply this approach to some of the other texts and traditions that made up the poetic ecology of archaic Greece, in order to illustrate the diversity of this ecology and the contrast between two of its most important “habitats,” or contexts for performance: Panhellenic festivals and the symposium. I will examine representative examples from the lyric and elegiac traditions associated with the poets Alcaeus of Mytilene and Theognis of Megara, respectively, and I will cast a concluding glance over the Odyssey, which sketches an illuminating contrast between festival and symposium. I begin, however, by distilling some of the most important claims from my earlier work in order to establish a framework for my discussion. Scholars have been interested in the politics of the Homeric poems since antiquity. Ancient critics tended to draw from the poems lessons about proper political conduct, in accordance with a general tendency to view Homer as the great primordial educator of the Greeks. -

Sappho of Lesbos [Born C

Sappho of Lesbos [born c. 612 B.C.] Know the following people, places, and terms: Aphrodite (=Kypris [refers to her sanctuary on Cyprus], =Cytherea [refers to her sanctuary on Cythera]) Eros, Aphrodite's son (sometimes known as Boy, Love or Cupid) Helen, wife of Menelaus, abducted by Paris to Troy Artemis, sister of Phoebus Apollo, goddess of the hunt Hector, greatest of the Trojan warriors, son of King Priam Andromache, Hector's wife Sardis, a town in Lydia, the area of Asia Minor across from Lesbos choriamb: − ∪ ∪ − Sapphic meter: three hendecasyllabic lines − ∪ − x | − ∪ ∪ − | ∪ − − followed by an Adonean − ∪ ∪ − | − 1. What is Sappho's world like? With whom does she associate and care for? What recurring images do we find in Sappho's poetry? In short, what did she value? 2. How is Aphrodite portrayed? Playful? Serious? Powerful? What were her powers? attributes? How does Sappho's view of Aphrodite compare with Homer's and Hesiod's? Whose view do you prefer? 3. What is Sappho's attitude toward love? Does Sappho's portrayal of Aphrodite (her theory of love, if you will) correspond to her actual relationships (i.e. the practice of love)? 4. What kind of relationship did Sappho have with her hetairai , "female companions"? Was it physical as well as emotional? Was there an intellectual component? If you were to speculate, what were the reasons for Sappho's attachment to her companions? What evidence is there that Sappho's hetairai were attracted to her? Is there any evidence in her poems of the erastes-eromenos relationship that we see in classical Athens? 5. -

De Theognide Megarensi. Nietzsche on Theognis of Megara. a Bilingual Edition

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE De Theognide Megarensi Nietzsche on Theognis of Megara – A Bilingual Edition – Translated by R. M. Kerr THE NIETZSCHE CHANNEL Friedrich Nietzsche De Theognide Megarensi Nietzsche on Theognis of Megara A bilingual edition Translated by R. M. Kerr ☙ editio electronica ❧ _________________________________________ THE N E T ! " # H E # H A N N E $ % MM&' Copyright © Proprietas interpretatoris Roberti Martini Kerrii anno 2015 Omnia proprietatis iura reservantur et vindicantur. Imitatio prohibita sine auctoris permissione. Non licet pecuniam expetere pro aliquo, quod partem horum verborum continet; liber pro omnibus semper gratuitus erat et manet. Sic rerum summa novatur semper, et inter se mortales mutua vivunt. augescunt aliae gentes, aliae invuntur, inque brevi spatio mutantur saecla animantum et quasi cursores vitai lampada tradiunt. - Lucretius - - de Rerum Natura, II 5-! - PR"#$CE %e &or' presente( here is a trans)ation o* #rie(rich Nietzsche-s aledi!tionsarbeit ./schoo) e0it-thesis12 *or the "andesschule #$orta in 3chu)p*orta .3axony-$nhalt) presente( on 3epte4ber th 15678 It has hitherto )arge)y gone unnotice(, especial)y in anglophone Nietzsche stu(- ies8 $t the ti4e though, the &or' he)pe( to estab)ish the reputation o* the then twenty year o)( Nietzsche and consi(erab)y *aci)itate( his )ater acade4ic career8 9y a)) accounts, it &as a consi(erab)e achie:e4ent, especial)y consi(ering &hen it &as &ri;en: it entai)e( an e0pert 'no&)e(ge, not =ust o* c)assical-phi)o)ogical )iterature, but also o* co(ico)ogy8 %e recent =u(ge4ent by >"+3"+ .2017<!!2< “It is a piece that, ha( Nietzsche ne:er &ri;en another &or(, &ou)( ha:e assure( his p)ace, albeit @uite a s4a)) one, in the history o* Ger4an phi)o)ogyB su4s the 4atter up quite e)o@uently8 +ietzsche )ater continue( his %eognis stu(ies, the sub=ect o* his Crst scho)ar)y artic)e, as a stu(ent at Leip,ig, in 156 D to so4e e0tent a su44ary o* the present &or' D a critical re:ie& in 156!, as &e)) as @uotes in se:eral )e;ers *ro4 1567 on. -

The Role of Aphrodite in Sappho Fr. 1 Keith Stanley

The Rôle of Aphrodite in Sappho Fr.1 Stanley, Keith Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1976; 17, 4; ProQuest pg. 305 The Role of Aphrodite in Sappho Fr. 1 Keith Stanley APPHO'S Hymn to Aphrodite, standing so near to the beginning of Sour evidence for the religious and poetic traditions it embodies, remains a locus of disagreement about the function of the goddess in the poem and the degree of seriousness intended by Sappho's plea for her help. Wilamowitz thought sparrows' wings unsuited to the task of drawing Aphrodite's chariot, and proposed that Sappho's report of her epiphany described a vision experienced ovap, not v7rap.l Archibald Cameron ventured further, suggesting that the description of Aphrodite's flight was couched not in the language of "the real religious tradition of epiphany and its effect on mortals" but was "Homeric and conventional"; and that the vision was not, therefore, the record of a genuine religious experience, but derived rather from "the bright world of Homer's fancy."2 Thus he judged the tone of the ode to be one of seriousness tempered by "a vein of prettiness and almost of playfulness" and concluded that there was no special ur gency in Sappho's petition itself. While more recent opinion has tended to regard the episode as a poetic fiction which serves to 'mythologize' a genuine emotion, Sir Denys Page has not only maintained that Aphrodite's descent is a "flight of fancy, with much detail irrelevant to her present theme," but argued further that the poem as a whole is a lightly ironic melange of passion and self-mockery.3 Despite a con- 1 Sappho und Simonides (Berlin 1913) 45, with Der Glaube der Hellenen 3 II (Basel 1959) 109; so also J. -

Select Epigrams from the Greek Anthology

SELECT EPIGRAMS FROM THE GREEK ANTHOLOGY J. W. MACKAIL∗ Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. PREPARER’S NOTE This book was published in 1890 by Longmans, Green, and Co., London; and New York: 15 East 16th Street. The epigrams in the book are given both in Greek and in English. This text includes only the English. Where Greek is present in short citations, it has been given here in transliterated form and marked with brackets. A chapter of Notes on the translations has also been omitted. eti pou proima leuxoia Meleager in /Anth. Pal./ iv. 1. Dim now and soil’d, Like the soil’d tissue of white violets Left, freshly gather’d, on their native bank. M. Arnold, /Sohrab and Rustum/. PREFACE The purpose of this book is to present a complete collection, subject to certain definitions and exceptions which will be mentioned later, of all the best extant Greek Epigrams. Although many epigrams not given here have in different ways a special interest of their own, none, it is hoped, have been excluded which are of the first excellence in any style. But, while it would be easy to agree on three-fourths of the matter to be included in such a scope, perhaps hardly any two persons would be in exact accordance with regard to the rest; with many pieces which lie on the border line of excellence, the decision must be made on a balance of very slight considerations, and becomes in the end one rather of personal taste than of any fixed principle. For the Greek Anthology proper, use has chiefly been made of the two ∗PDF created by pdfbooks.co.za 1 great works of Jacobs, -

Collins Magic in the Ancient Greek World.Pdf

9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page i Magic in the Ancient Greek World 9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page ii Blackwell Ancient Religions Ancient religious practice and belief are at once fascinating and alien for twenty-first-century readers. There was no Bible, no creed, no fixed set of beliefs. Rather, ancient religion was characterized by extraordinary diversity in belief and ritual. This distance means that modern readers need a guide to ancient religious experience. Written by experts, the books in this series provide accessible introductions to this central aspect of the ancient world. Published Magic in the Ancient Greek World Derek Collins Religion in the Roman Empire James B. Rives Ancient Greek Religion Jon D. Mikalson Forthcoming Religion of the Roman Republic Christopher McDonough and Lora Holland Death, Burial and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt Steven Snape Ancient Greek Divination Sarah Iles Johnston 9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page iii Magic in the Ancient Greek World Derek Collins 9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page iv © 2008 by Derek Collins blackwell publishing 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Derek Collins to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece

Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Ancient Greek Philosophy but didn’t Know Who to Ask Edited by Patricia F. O’Grady MEET THE PHILOSOPHERS OF ANCIENT GREECE Dedicated to the memory of Panagiotis, a humble man, who found pleasure when reading about the philosophers of Ancient Greece Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece Everything you always wanted to know about Ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask Edited by PATRICIA F. O’GRADY Flinders University of South Australia © Patricia F. O’Grady 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Patricia F. O’Grady has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identi.ed as the editor of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington Surrey, GU9 7PT VT 05401-4405 England USA Ashgate website: http://www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Meet the philosophers of ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask 1. Philosophy, Ancient 2. Philosophers – Greece 3. Greece – Intellectual life – To 146 B.C. I. O’Grady, Patricia F. 180 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Meet the philosophers of ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask / Patricia F. -

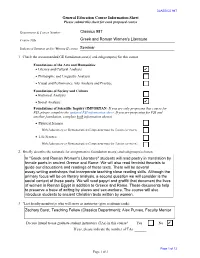

CLASSICS 98T General Education Course Information Sheet Please Submit This Sheet for Each Proposed Course

CLASSICS 98T General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Course Title Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities ñ Literary and Cultural Analysis ñ Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis ñ Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture ñ Historical Analysis ñ Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry (IMPORTAN: If you are only proposing this course for FSI, please complete the updated FSI information sheet. If you are proposing for FSI and another foundation, complete both information sheets) ñ Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) ñ Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs Page 1 of 12 Page 1 of 3 CLASSICS 98T 4. Indicate when do you anticipate teaching this course over the next three years: 2018-19 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 2019-20 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 2020-21 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 5. GE Course Units Is this an existing course that has been modified for inclusion in the new GE? Yes No If yes, provide a brief explanation of what has changed: Present Number of Units: Proposed Number of Units: 6. -

Archaic Lyric Voices

Archaic Lyric Voices An Introduction to Three Greek Lyric Poets: Alcman, Alcaeus, and Sappho The aim of this short article is to provide an introduction to three lyric poets of the archaic period, Alcman, Alcaeus, and Sappho. We will examine each poet and examples of his or her poetry individually, while at the same time exploring some overarching themes. I will throughout consider how and to what extent the poetry of these authors is different from the well known epics of Homer, the Iliad and Odyssey, and whether there is any continuity. I will also look at the performance context, mode, and tone of the poetry to give a sense of what is individual and unique about the poetry of Alcman, Alcaeus, and Sappho. Let me begin by situating these three poets chronologically in the tradition of Greek poetry and geographically in the ancient Greek world. The dates of literary activity I am about to mention are approximate, as our knowledge of the lives of these poets is in most cases quite scanty, but they will at least give you a sense of when these poets were working. The locations are more certain, and, as we will see, very important for the understanding of the lyric poetry. Now, the Iliad and the Odyssey attributed in antiquity to the blind bard Homer, although derived from a long oral tradition, were put into a form close to that which we have today between the end of the 8th and middle of the first half of the 7th century B.C.E., most probably in Ionia. -

Eroticism in Theognis Josh C

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK World Languages, Literatures and Cultures World Languages, Literatures and Cultures Undergraduate Honors Theses 5-2015 Eroticism in Theognis Josh C. Koerner University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/wllcuht Recommended Citation Koerner, Josh C., "Eroticism in Theognis" (2015). World Languages, Literatures and Cultures Undergraduate Honors Theses. 2. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/wllcuht/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages, Literatures and Cultures at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages, Literatures and Cultures Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Eroticism in Theognis An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors Studies in Classical Studies By: Joshua Koerner 2015 Classics J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences The University of Arkansas Introduction and Background to Theognis 3 Background to Symposium 13 Eroticism in the Theognidean Corpus 25 Appendices 75 Bibliography 122 Acknowledgements 125 !2 of !125 Introduction and Background to Theognis Understanding masculinity and the way it self-defines is an integral part of understanding symposia as “masculine,” and using an elite context inherently includes in its discussion a greater degree of contrast between the self, or the community that identifies in a particular way, and the other. Further, given that sexuality is an integral component to the human experience, it is quite relevant to pursue the question of eroticism in a general context as well as the specific. -

Theognis of Megara Translated by Gregory Nagy

Theognis of Megara Translated by Gregory Nagy Lord Apollo, son of Leto and Zeus, I will always have you 2 on my mind as I begin and as I end my song. You will be my song in the beginning, in the end, and in the middle. 4 Hear my prayer and grant me the things that are noble [esthla]. Lord Phoebus Apollo! When the goddess, Lady Leto, gave birth to you 6 at the wheel-shaped lake, you O most beautiful of the immortal gods, as she held on to the Palm Tree with her supple hands, 8 then it was that all Delos, indescribably and eternally, was filled with an aroma of immortality; and the Earth smiled in all her enormity, 10 while the deep pontos of the gray Sea rejoiced. Artemis, killer of beasts, daughter of Zeus! For you Agamemnon 12 established a sacred precinct at the time when he set sail for Troy with his swift ships. Hear my prayer! Ward off the spirits of destruction! 14 For you this is a small thing to do, goddess. For me it is a big thing. 15 Muses and Graces [Kharites], daughters of Zeus! You were the ones 16 who once came to the wedding of Kadmos, and you sang this beautiful epos: 17 “What is beautiful [kalon] is near and dear [philon], what is not beautiful [kalon] is not near and dear [philon].” 18 That is the epos that came through their immortal mouths. Kyrnos, let a seal be placed by me as I practice my sophiā 20 upon these epea; that way they will never be stolen without detection, and no one will substitute something inferior for the good [esthlon] that is there. -

Harrison on Theognis Studies in Theognis, Together with a Text of the Poems

The Classical Review http://journals.cambridge.org/CAR Additional services for The Classical Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Harrison on Theognis Studies in Theognis, together with a Text of the Poems. By E. Harrison, B.A., Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. Cambridge: University Press, 1902. Pp. xii, 336. 10s. 6d. net. Herbert Weir Smyth The Classical Review / Volume 17 / Issue 07 / October 1903, pp 352 - 356 DOI: 10.1017/S0009840X00208512, Published online: 27 October 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0009840X00208512 How to cite this article: Herbert Weir Smyth (1903). Review of Ennis B. Edmonds, and Michelle A. Gonzalez 'Caribbean Religious History: An Introduction' The Classical Review, 17, pp 352-356 doi:10.1017/S0009840X00208512 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CAR, IP address: 128.122.253.212 on 08 May 2015 352 THE CLASSICAL REVIEW. REVIEWS. HARBISON ON THEOGNIS. Studies in Tlieognis, together with a Text in almost any order as in their present of the Poems. By E. HARRISON, B.A., position. Welcker first suggested the Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. theory of 'catchwords.' In 1867 Cambridge: University Press, 1902. Nietzsche dealt with this method of Pp. xii, 336. 10s. 6d. net. explanation and with the repetitions. In 1869 Fritzsche toyed with the problem of WITH all divergencies of detail criti- catchwords, which he accepted as correct in cism of Theognis during the nineteenth the main; in 1877 K. Miiller came to the century has been well-nigh unanimous on conclusion that similarity of mere words in two points : many of the poems found in adjoining poems constituted the principle of the MSS.