147829667.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Edith Wyle, 1993 March 9-September 7

Oral history interview with Edith Wyle, 1993 March 9-September 7 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview EW: EDITH WYLE SE: SHARON EMANUELLI SE: This is an interview for the Archives of American Art, the Smithsonian Institution. The interview is with Edith R. Wyle, on March 9th, Tuesday, 1993, at Mrs. Wyle's home in the Brentwood area of Los Angeles. The interviewer is Sharon K. Emanuelli. This is Tape 1, Side A. Okay, Edith, we're going to start talking about your early family background. EW: Okay. SE: What's your birth date and place of birth? EW: Place of birth, San Francisco. Birth date, are you ready for this? April 21st, 1918-though next to Beatrice [Wood-Ed.] that doesn't seem so old. SE: No, she's having her 100th birthday, isn't she? EW: Right. SE: Tell me about your grandparents. I guess it's your maternal grandparents that are especially interesting? EW: No, they all were. I mean, if you'd call that interesting. They were all anarchists. They came from Russia. SE: Together? All together? EW: No, but they knew each other. There was a group of Russians-Lithuanians and Russians-who were all revolutionaries that came over here from Russia, and they considered themselves intellectuals and they really were self-educated, but they were very learned. -

General Info.Indd

General Information • Landmarks Beyond the obvious crowd-pleasers, New York City landmarks Guggenheim (Map 17) is one of New York’s most unique are super-subjective. One person’s favorite cobblestoned and distinctive buildings (apparently there’s some art alley is some developer’s idea of prime real estate. Bits of old inside, too). The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (Map New York disappear to differing amounts of fanfare and 18) has a very medieval vibe and is the world’s largest make room for whatever it is we’ll be romanticizing in the unfinished cathedral—a much cooler destination than the future. Ain’t that the circle of life? The landmarks discussed eternally crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Map 12). are highly idiosyncratic choices, and this list is by no means complete or even logical, but we’ve included an array of places, from world famous to little known, all worth visiting. Great Public Buildings Once upon a time, the city felt that public buildings should inspire civic pride through great architecture. Coolest Skyscrapers Head downtown to view City Hall (Map 3) (1812), Most visitors to New York go to the top of the Empire State Tweed Courthouse (Map 3) (1881), Jefferson Market Building (Map 9), but it’s far more familiar to New Yorkers Courthouse (Map 5) (1877—now a library), the Municipal from afar—as a directional guide, or as a tip-off to obscure Building (Map 3) (1914), and a host of other court- holidays (orange & white means it’s time to celebrate houses built in the early 20th century. -

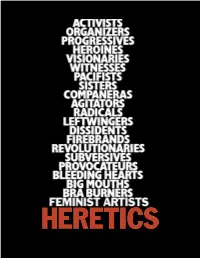

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Feminist Art, the Women's Movement, and History

Working Women’s Menu, Women in Their Workplaces Conference, Los Angeles, CA. Pictured l to r: Anne Mavor, Jerri Allyn, Chutney Gunderson, Arlene Raven; photo credit: The Waitresses 70 THE WAITRESSES UNPEELED In the Name of Love: Feminist Art, the Women’s Movement and History By Michelle Moravec This linking of past and future, through the mediation of an artist/historian striving for change in the name of love, is one sort of “radical limit” for history. 1 The above quote comes from an exchange between the documentary videomaker, film producer, and professor Alexandra Juhasz and the critic Antoinette Burton. This incredibly poignant article, itself a collaboration in the form of a conversation about the idea of women’s collaborative art, neatly joins the strands I want to braid together in this piece about The Waitresses. Juhasz and Burton’s conversation is at once a meditation of the function of political art, the role of history in documenting, sustaining and perhaps transforming those movements, and the influence gender has on these constructions. Both women are acutely aware of the limitations of a socially engaged history, particularly one that seeks to create change both in the writing of history, but also in society itself. In the case of Juhasz’s work on communities around AIDS, the limitation she references in the above quote is that the movement cannot forestall the inevitable death of many of its members. In this piece, I want to explore the “radical limit” that exists within the historiography of the women’s movement, although in its case it is a moribund narrative that threatens to trap the women’s movement, fixed forever like an insect under amber. -

The Wooster Group the Town Hall Affair (In De Vorm Van Een Eenakter) Gebaseerd Op De Film ‘Town Bloody Hall’ Van Chris Hegedus & D.A

theater The Wooster Group The Town Hall Affair (in de vorm van een eenakter) gebaseerd op de film ‘Town Bloody Hall’ van Chris Hegedus & D.A. Pennebaker The Town Hall Affair 1. Intro: uittreksel ‘Lesbian Nation’ 2. Het stuk Bzymek © Zbigniew 3. Coda: uittreksel ‘Lesbian Nation’ wo 21, do 22, vr 23 sep 2016 met licht Jennifer Tipton, Ryan Seelig geluid 20 uur / Theaterstudio Kate Valk Jill Johnston Eric Sluyter, Gareth Hobbs Ari Fliakos Norman Mailer/Norman video en projecties Robert Wuss za 24 sep 2016 Kingsley aanvullende video Zbigniew Bzymek 17 & 20.30 uur / Theaterstudio Scott Shepherd Norman Mailer/De kostuums Enver Chakartash regieas- Acteur sistentie Enver Chakartash, Matthew Lucy Taylor Germaine Greer/De Dipple productieleiding Bona Lee De voorstelling duurt ongeveer Echtgenote podiumregie Erin Mullin technische 1 uur, zonder pauze. Greg Mehrten Diana Trilling/De Vriend leiding Joseph Silovsky technische Erin Mullin Robyn/Ruth Mandel leiding tournee Eric Dyer productie Spreektaal Engels Gareth Hobbs (stem) Peter Fisher Cynthia Hedstrom zakelijke leiding boventiteling Enver Chakartash podiumassistentie Pamela Reichen Nederlands/Frans regie Elizabeth LeCompte speciale dank aan Matthias Neckermann en Sheena See. Na afloop van de voorstelling Bronnen: Town Bloody Hall, een documentaire van Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker, 1979, 88 min, op donderdag 22 september kleur. De film is een weergave van het Theater for Ideas debat uit 1971 met als titel ‘A Dialogue gaat Pieter T’jonck in gesprek on Women’s Liberation’ (‘Een dialoog over vrouwenemancipatie’). met Elizabeth LeCompte in de Maidstone, een film van Norman Mailer, 1970, 110 min, kleur. Een onafhankelijke film, geregis- Theaterstudio. -

Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive

Article Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive Kathy Carbone ABSTRACT The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The CalArts Feminist Art Program (1971–1975) played an influential role in this movement and today, traces of the Feminist Art Program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection. Through a series of short interrelated archives stories, this paper explores some of the ways in which women responded to and engaged the Collection, especially a series of letters, for feminist projects at CalArts and the Women’s Art Library at Goldsmiths, University of London over the period of one year (2017–2018). The paper contemplates the archive as a conduit and locus for current day feminist identifications, meaning- making, exchange, and resistance and argues that activating and sharing—caring for—the archive’s feminist art histories is a crucial thing to be done: it is feminism-in-action that not only keeps this work on the table but it can also give strength and definition to being a feminist and an artist. Carbone, Kathy. “Dear Sister Artist,” in “Radical Empathy in Archival Practice,” eds. Elvia Arroyo- Ramirez, Jasmine Jones, Shannon O’Neill, and Holly Smith. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3. ISSN: 2572-1364 INTRODUCTION The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) Feminist Art Program, which ran from 1971 through 1975, played an influential role in this movement and today, traces and remains of this pioneering program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection (henceforth the “Collection”). -

“My Personal Is Not Political?” a Dialogue on Art, Feminism and Pedagogy

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 5, No. 2, July 2009 “My Personal Is Not Political?” A Dialogue on Art, Feminism and Pedagogy Irina Aristarkhova and Faith Wilding This is a dialogue between two scholars who discuss art, feminism, and pedagogy. While Irina Aristarkhova proposes “active distancing” and “strategic withdrawal of personal politics” as two performative strategies to deal with various stereotypes of women's art among students, Faith Wilding responds with an overview of art school’s curricular within a wider context of Feminist Art Movement and the radical questioning of art and pedagogy that the movement represents Using a concrete situation of teaching a women’s art class within an art school environment, this dialogue between Faith Wilding and Irina Aristakhova analyzes the challenges that such teaching represents within a wider cultural and historical context of women, art, and feminist performance pedagogy. Faith Wilding has been a prominent figure in the feminist art movement from the early 1970s, as a member of the California Arts Institute’s Feminist Art Program, Womanhouse, and in the recent decade, a member of the SubRosa, a cyberfeminist art collective. Irina Aristarkhova, is coming from a different history to this conversation: generationally, politically and theoretically, she faces her position as being an outsider to these mostly North American and, to a lesser extent, Western European developments. The authors see their on-going dialogue of different experiences and ideas within feminism(s) as an opportunity to share strategies and knowledges towards a common goal of sustaining heterogeneity in a pedagogical setting. First, this conversation focuses on the performance of feminist pedagogy in relation to women’s art. -

New Editions 2012

January – February 2013 Volume 2, Number 5 New Editions 2012: Reviews and Listings of Important Prints and Editions from Around the World • New Section: <100 Faye Hirsch on Nicole Eisenman • Wade Guyton OS at the Whitney • Zarina: Paper Like Skin • Superstorm Sandy • News History. Analysis. Criticism. Reviews. News. Art in Print. In print and online. www.artinprint.org Subscribe to Art in Print. January – February 2013 In This Issue Volume 2, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Visibility Associate Publisher New Editions 2012 Index 3 Julie Bernatz Managing Editor Faye Hirsch 4 Annkathrin Murray Nicole Eisenman’s Year of Printing Prodigiously Associate Editor Amelia Ishmael New Editions 2012 Reviews A–Z 10 Design Director <100 42 Skip Langer Design Associate Exhibition Reviews Raymond Hayen Charles Schultz 44 Wade Guyton OS M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp 46 Zarina: Paper Like Skin New Editions Listings 48 News of the Print World 58 Superstorm Sandy 62 Contributors 68 Membership Subscription Form 70 Cover Image: Rirkrit Tiravanija, I Am Busy (2012), 100% cotton towel. Published by WOW (Works on Whatever), New York, NY. Photo: James Ewing, courtesy Art Production Fund. This page: Barbara Takenaga, detail of Day for Night, State I (2012), aquatint, sugar lift, spit bite and white ground with hand coloring by the artist. Printed and published by Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, NH. Art in Print 3500 N. Lake Shore Drive Suite 10A Chicago, IL 60657-1927 www.artinprint.org [email protected] No part of this periodical may be published without the written consent of the publisher. -

Copyrighted Material

09_573837 ch05.qxd 12/14/04 11:17 PM Page 85 5 Family-Friendly Dining In the gastronomic universe, New revolving showcase of whipped York has a fair number of star-quality cream–topped desserts. A number of restaurants, but are they worth it if trendy retro coffee shops have opened you’re eating out with your kids? in recent years, adding upscale parent- Fuhgeddaboudit. Le Bernardin and pleasing food to the traditional menu Nobu be damned—what I look for of burgers, omelets, and grilled cheese these days is a restaurant that’s noisy sandwiches. and casual, where the service is rela- I’m not a big fan of eating at side- tively speedy, and where the menu walk tables—I’d rather get away from includes at least one or two items from traffic and exhaust—but as soon as the my kids’ major food groups: chicken weather warms up, many families opt fingers, burgers, pasta, pancakes, and for restaurants with sidewalk seating. pizza, any or all of which could come The open-air arrangement minimizes with a side of fries. You can find your child’s noise, provides endless plenty of such restaurants in New distraction, and makes messes less York, and they won’t cost you an arm important (there’s always a pigeon or and a leg. two around to peck up dropped DINING OUT WITH YOUR KIDS french fries after you’ve cleared off). You know a restaurant welcomes kids Knowing how many Manhattan when they’ve printed up a place mat restaurants don’t work for smaller chil- for young customers to color and dren, for the most part I’ve tried to when you get to keep the crayons steer you towards those that do, you’re given to color it with. -

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond. -

Cassandra Langer Interviewed by Katie Cercone Date: Dec

NYFAI - Interview: Cassandra Langer interviewed by Katie Cercone Date: Dec. 15th, 2008 K.C. This is December 15th, 2008, Katie Cercone interviewing Cassandra Langer. C.L. I think it was important for most of us during the early 70s when the movement started up to establish institutions that would be accommodating to the radical new ideas that we had. We rejected the idea of accepting the old roles; of getting married being wives, and mothers . I think it’s hard for young people to understand that was the life you were groomed for. If you aspired to anything else, you were deemed oddball out , rushed off to a psychoanalyst or worse yet, thrown into a mental institution for readjustment. Establishing the Feminist Art Institute was an extremely revolutionary thing to do at that time. NYFAI provided a safe space for creative women who were trying to break out of those stereotypes. There was the California site that my friend Arlene Raven and others including Mimi Schapiro and Judy Chicago set up within the heart of a traditionally patriarchal art department spawning Woman House and other alternative spaces. Mimi, Nancy and people in New York, set up their own versions to begin with but they evolved into the Feminist Art Institute. For people like myself who were outsider-insiders, because I was teaching in South Carolina in the heart of limitation land and bigotry it was an oasis. The freedom of being able to talk with like-minded people was empowering. Founding the Collage Art Association’s Women’s Caucus for Art helped a lot. -

California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Materials Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2199r38x No online items Guide prepared by Abigail Dixon for History Associates Incorporated California Institute of the Arts California Institute of the Arts Archive California Institute of the Arts 24700 McBean Parkway Valencia, California 91355-2397 Phone: (661) 253-7882 Fax: (661) 254-4561 Email: [email protected] URL: http://calarts.edu/library/collections/archive 2008 CalArts-003 1 Administrative Summary Creator: California Institute of the Arts Title: California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Materials Collection Dates: 1971-2007 Date (bulk): (bulk 1972-1977) Quantity: 2.3 cubic feet Repository: California Institute of the Arts. Library. Valencia, California 91355-2397 Abstract: The California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Materials Collection contains articles, brochures, correspondence, exhibition catalogs, invoices, newsletters, and other materials documenting the influence of feminism on the training of artists and the making of art. The collection covers the years 1971 to 2007 with the bulk of the material ranging from 1972 to 1977. California Institute of the Arts Archive Identification: CalArts-003 Language of Material: English Restrictions on Access This collection is open for research with permission from California Institute of the Arts Archive staff. Publication Rights Property rights and literary rights reside with California Institute of the Arts. For permission to reproduce or to publish, please contact California Institute of the Arts Archive staff. Related Material Located in the California Institute of the Arts Archive Archives Unprocessed collections with related material are located in the CalArts Library Archives. Preferred Citation California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Materials Collection.