The Resurgence of Naxalism: How Great a Threat to India?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Memorable Condolence Meeting in Hyderabad on 27-4-2015

Don't 15Pull thousand Back Podu Adivasi Lands from and Adivasis other tribals’ other tribals 15 thousandDharna Adivasi in Hyderabad and other tribals’Maha on 25-06-2015 Dharna Demand 15 thousand Adivasi and other tribals Participated the Maha Dharna in Hyderabad on 25th May 2015 Since the KCR government came to power, Under the leadership of the party Adivasis the forest official intensified their efforts to throw fought against forest officials started cutting unre- out the Adivasis and other tribals from their Podu served forest and re-occupying their lands. In this lands and occupy their lands forcefully to implant process Podu cultivation also started by the time of teak and other seedlings in those lands. For more emergency. For the last four decades Adivasis have than four and half decades the Adivasis have been been cultivating their podu lands. The adivasis have fighting against the unjust and autocratic methods been demanding Pattas for their lands. Before every of forest officials in the Godavari valley under the elections ruling class parties used to promise for leadership of our party. Forest officials closetted the giving pattas to the Adivasis and other tribes. Soon reserve forest lines into the lands of the Adivasis. after the elections they,in general, forget their They were not allowed to bring firewood and even demands. However, KCR immediately after coming material for broomstick and leaves for taking food to power started anti-Adivasi crusade while prom- etc. Non tribes illegally taken thousands of ising to give 3 acres of land to poor people. Adivasis’ lands giving petty amounts or nothing With the intensification of forest officials and resorting to collect exhorbitant interest rates harassments like fencing the fields of Adivasis, call- from the Adivasis. -

Locating Activist Spaces: the Neighbourhood As a Source and Site of Urban Activism in 1970S Calcutta

Cultural Dynamics 23(1) 21–40 Locating Activist Spaces: © The Author(s) 2011 Reprints and permissions: The Neighbourhood as a sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0921374011403352 Source and Site of Urban cdy.sagepub.com Activism in 1970s Calcutta Henrike Donner London School of Economics and Political Science Abstract This article analyses the meaning of urban neighbourhoods for the emergence of Maoist activism in 1970s Calcutta. Through ethnography the article highlights the way recruitment, strategies and the legacy of the movement were located in the experience and politics of the urban neighbourhood. As a social formation, the neighbourhood shaped the relationships that made Maoist subjectivities feasible and provided the space for coalitions and cooperation across a wider spectrum than the label of a student movement acknowledges. The neighbourhood appears here as an emergent site for Maoist epistemologies, which depended on this space and its everyday practices, intimate social relations as well as the experience of the local state in the locality. Keywords activism, India, Maoists, neighbourhood, urban Introduction In spite of the focus of much recent research on contemporary urban South Asia, and an increasing interest in social movements on the subcontinent, the two bodies of literature and the questions they raise are rarely thought together. Moreover, contemporary ‘progressive urban movements’ remain largely unanalysed, unless they take the form of globally recognizable labour politics. This article represents an attempt to think activism and urbanism in contemporary South Asia together through the ethnography of Maoist activism in 1970s Calcutta, and I will zoom in on a specific set of relationships, social and material, political and economical, which shaped this movement, namely the urban neighbourhood.1 Corresponding author: Henrike Donner, Department of Anthropology, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE, UK. -

Central Committee

COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MAOIST) Central Committee Press Release 10 November 2018 As the General Secretary of CPI (Maoist) Comrade Ganapathy has voluntarily withdrawn from his responsibilities, the Central Committee has elected Comrade Basavaraju as the new General Secretary In view of his growing ill-health and advancing age in the past few years and with the aim of strengthening the Central Committee and with a vision of the future, Comrade Ganapathy voluntarily withdrew from the responsibilities of General Secretary and placed a proposal to elect another comrade as General Secretary in his place, following which the 5th meeting of the Central Committee thoroughly discussed his proposal and after accepting it, elected Comrade Basavaraju (Namballa Kesava Rao) as the new General Secretary. Comrade Ganapathy was elected as the General Secretary of the CPI(ML)(People’s War) in June 1992. That was a very difficult time for the Party. By 1991, the Andhra Pradesh government started the second phase of repression on the Party. The Party was facing several challenges at that time regarding the tactics to be adopted to advance the armed struggle. The then secretary of the Central Committee, Kondapalli Seetharamaiah, was not in a position to overcome those challenges that the Party was facing by leading his committee. In such conditions, instead of overcoming those challenges by basing on all the Party cadres and the people, Kondapalli Seetharamaiah and another member of the Central Committee followed conspiratorial methods and became the cause of internal crisis in the Party. Except a few opportunists, the whole Party stood united in the principled fight against this opportunist clique which made attempts to split the Party. -

SPARROW Newsletter

SNL Number 38 May 2019 SPARROW newsletter SOUND & PICTURE ARCHIVES FOR RESEARCH ON WOMEN A Random Harvest: A book of Diary sketches/ Drawings/Collages/ Watercolours of Women Painters It is a random collection from the works women painters who supported the Art Raffle organised by SPARROW in 2010. The works were inspired by or were reflections of two poems SPARROW gave them which in our view, exemplified joy and sorrow and in a sense highlighted women’s life and experiences that SPARROW, as a women’s archives, has been documenting over the years. Contribution Price: Rs. 350/- This e-book is available in BookGanga.com. Photographs............................................. 19267 Ads................................................................ 7449 Books in 12 languages............................ 5728 Newspaper Articles in 8 languages... 31018 Journal Articles in 8 languages..............5090 Brochures in 9 languages........................2062 CURRENT Print Visuals................................................. 4552 Posters........................................................... 1772 SPARROW Calendars...................................................... 129 Cartoons..............................................................3629 Maya Kamath’s cartoons...........................8000 HOLDINGS Oral History.................................................. 659 Video Films................................................. 1262 Audio CDs and Cassettes...................... 929 Private Papers........................................ -

Red Bengal's Rise and Fall

kheya bag RED BENGAL’S RISE AND FALL he ouster of West Bengal’s Communist government after 34 years in power is no less of a watershed for having been widely predicted. For more than a generation the Party had shaped the culture, economy and society of one of the most Tpopulous provinces in India—91 million strong—and won massive majorities in the state assembly in seven consecutive elections. West Bengal had also provided the bulk of the Communist Party of India– Marxist (cpm) deputies to India’s parliament, the Lok Sabha; in the mid-90s its Chief Minister, Jyoti Basu, had been spoken of as the pos- sible Prime Minister of a centre-left coalition. The cpm’s fall from power also therefore suggests a change in the equation of Indian politics at the national level. But this cannot simply be read as a shift to the right. West Bengal has seen a high degree of popular mobilization against the cpm’s Beijing-style land grabs over the past decade. Though her origins lie in the state’s deeply conservative Congress Party, the challenger Mamata Banerjee based her campaign on an appeal to those dispossessed and alienated by the cpm’s breakneck capitalist-development policies, not least the party’s notoriously brutal treatment of poor peasants at Singur and Nandigram, and was herself accused by the Communists of being soft on the Maoists. The changing of the guard at Writers’ Building, the seat of the state gov- ernment in Calcutta, therefore raises a series of questions. First, why West Bengal? That is, how is it that the cpm succeeded in establishing -

Assessing the Promise and Limitations of Joint Forest Management in an Era of Globalisation: the Case of West Bengal.1

Assessing the promise and limitations of Joint Forest Management in an era of globalisation: the case of West Bengal.1 Douglas Hill, Australian National University. Introduction This paper seeks to interrogate the claims of the dominant discourses of globalisation with regard to their compatibility with mechanisms for empowering marginalised communities and providing a basis for sustainable livelihood strategies. These concerns are examined from the perspective of the development experience of India, including the New Economic Policy (NEP) regime initiated in India in 1991, and its subsequent structural transformation towards greater conformity with the imperatives of ‘economic liberalisation’. It suggests that the Indian institutional structure of development has been such that resources have been unequally distributed and that this has reinforced certain biases particularly on a caste/class and gender basis. The analysis suggests that these biases have reduced the legitimacy of previous models of resource management and continue to hamper the prospects of current formulations. These concerns are analysed utilising an examination of the management of forest-based Common Property Resources (CPRs) within the context of rural West Bengal, specifically the system of Joint Forest Management (JFM) i. Such an examination is pertinent since those communities dependent upon CPRs for a substantial part of their subsistence requirements are amongst the most vulnerable strata of society. As Agrawhal, (1999), Platteau (1999, 1997) and others have argued, these CPRs function as a “social safety net” or “fall-back position”ii. This should be seen within the broader context of rural development, since the success or failure of the total rural development environment including poverty alleviation programs, agriculture, rural credit and employment (both on and off farm), will influence the relative dependence on these CPRs. -

India's Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 22 India’s Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S.-India Security Cooperation on Domestic Counterinsurgency by Thomas F. Lynch III Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for Technology and National Security Policy. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Hard-line communists, belonging to the political group Naxalite, pose with bows and arrows during protest rally in eastern Indian city of Calcutta December 15, 2004. More than 5,000 Naxalites from across the country, including the Maoist Communist Centre and the Peoples War, took part in a rally to protest against the government’s economic policies (REUTERS/Jayanta Shaw) India’s Naxalite Insurgency India’s Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S.-India Security Cooperation on Domestic Counterinsurgency By Thomas F. Lynch III Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. -

The Rising Tide of Left Wing Extremism in India and Implications for National Security

MANEKSHAW PAPER No. 8, 2008 The Rising Tide of Left Wing Extremism in India and Implications for National Security Amit Kumar Singh KONWLEDGE WORLD KW Publishers Pvt Ltd Centre for Land Warfare Studies New Delhi in association with New Delhi Centre for Land Warfare Studies Editorial Team Editor-in-Chief : Brig Gurmeet Kanwal (Retd) Managing Editor : Dr N Manoharan Copy Editor : Ms Rehana Mishra KONWLEDGE WORLD www.kwpublishers.com © 2009, Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Published in India by Kalpana Shukla KW Publishers Pvt Ltd NEW DELHI: 4676/21, First Floor, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110002 MUMBAI: 15 Jay Kay Industrial Estate, Linking Road Extn., Santacruz (W), Mumbai 400054 email: [email protected] Printed at Parangat Offset Pvt Ltd, New Delhi M ANEKSHAW PA The Rising Tide of Left Wing Extremism in India and P Implications for National Security ER NO . 8, 2009 AMIT KUMAR SINGH Left wing extremism (henceforth referred to as LWE) has emerged as one of the major security challenges in the South Asian region. This cannot merely be perceived as a manifestation of the prolonged state-building process that the states within the region have been undergoing. The movement could also be interpreted as an effort towards dismantling the prevailing unequal socio- economic and political structures that are understood by these radical left wing groups to have been serving the interests of upper strata of the society. -

Intellectuals and the Maoists

Intellectuals and the Maoists Uddipan Mukherjee∗ A revolution, insurgency or for that matter, even a rebellion rests on a pedestal of ideology. The ‘ideology’ could be a contested one – either from the so-called leftist or the rightist perspective. As ideology is of paramount importance, so are ‘intellectuals’. This paper delves into the concept of ‘intellectuals’. Thereafter, the role of the intellectuals in India’s Maoist insurgency is brought out. The issue turns out to be extremely topical considering the current discourse of ‘urban Naxals/ Maoists’. A few questions that need to be addressed in the discourse on who the Maoist intellectuals are: * Dr. Uddipan Mukherjee is a Civil Service officer and presently Joint Director at Ordnance Factory Board, Ministry of Defence, Government of India. He earned his PhD from the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Department of Atomic Energy. He was part of a national Task Force on Left Wing Extremism set up by the think tank VIF. A television commentator on Maoist insurgency, he has published widely in national and international journals/think-tanks/books on counterinsurgency, physics, history and foreign policy. He is the author of the book ‘Modern World History' for Civil Services. Views expressed in this paper are his own. Uddipan Mukherjee Are the intellectuals always anti-state? Can they bring about a revolution or social change? What did Gramsci, Lenin or Mao opine about intellectuals? Is the ongoing Left- wing Extremism aka Maoist insurgency in India guided by intellectuals? Do academics, -

Growing Tentacles and a Dormant State

Maoists in Orissa Growing Tentacles and a Dormant State Nihar Nayak* “Rifle is the only way to bring revolution or changes.”1 The growing influence of Left Wing extremists (also known as Naxalites)2 belonging to the erstwhile People’s War Group (PWG) and Maoist Communist Center (MCC) 3 along the borders of the eastern State of Orissa has, today, after decades of being ignored by the administration, become a cause for considerable alarm. Under pressure in some of its neighbouring States, the * Nihar Nayak is a Research Associate at the Institute for Conflict Management, New Delhi. 1 The statement made by Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) PWG Orissa Secretary, Sabyasachi Panda, in 1996. 2 The Naxalite movement takes its name from a peasant uprising, which occurred in May 1967 at Naxalbari in the State of West Bengal. It was led by armed Communist revolutionaries, who two years later were to form a party – the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (CPI-ML), under the leadership of Charu Mazumdar and Kanu Sanyal, who declared that they were implementing Mao Tse Tung’s ideas, and defined the objective of the new movement as 'seizure of power through an agrarian revolution'. The tactics to achieve this were through guerilla warfare by the peasants to eliminate the landlords and build up resistance against the state's police force which came to help the landlords; and thus gradually set up ‘liberated zones’ in different parts of the country that would eventually coalesce into a territorial unit under Naxalite hegemony. In this paper, the term ‘Naxalite’ has been used synonymously with ‘Maoist’ and ‘rebel’ to denote Left-Wing extremists. -

"NAXALITE" MOVEMENT in INDIA by Sharad Jhaveri

-518- We are not yet prepared to call ism, feudalism and comprador-bureaucrat the leaders of the CPI(M) "counter-revo- capital"! -- whatever that might mean. lutionaries" although objectively they play the role of defenders of bourgeois Indeed the "Naxalite" revolt against property. That is a logical consequence the leadership of the CPI(M) reflects to an of their opportunist class-collaboration- extent the growing revolt of the rank and ist policies emanating out of their er- file against the opportunist sins of the roneous and unhistorical strategy of a leadership. The ranks react in a blind and "people's democratic revolution'' in India. often adventurist manner to the betrayals of the masses by the traditional Stalinist But then the Naxalites, despite parties. all their fiery pronouncements regarding armed action and "guerrilla warfare," are For the present, Maoism, with its also committed to the strategy of a four- slogan "power flows from the barrel of a class "people's democratic front" -- a gun," has a romantic appeal to these rev- front of the proletariat with the peasant- olutionary romanticists. But the honest ry, middle class, and the national bour- revolutionaries among them will be con- geoisie to achieve a "people's democratic vinced in the course of emerging mass revolution. struggles that the alternative to the op- portunism of the CPI(M) is not Maoist ad- What is worse, the Naxalites under- venturism but a consciously planned rev- rate the role of the urban proletariat as olutionary struggle of workers and peas- the leaders of the coming socialist revo- ants, aimed at overthrowing the capital- lution in India. -

Searchable PDF Format

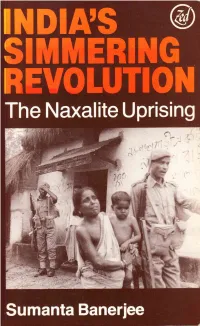

lndia's Simmering Revolution Sumanta Banerjee lndia's Simmeri ng Revolution The Naxalite Uprising Sumanta Banerjee Contents India's Simmering Revolution was first published in India under the title In the llake of Naxalbari: A History of the Naxalite Movement lVlirps in India by Subarnarekha, 73 Mahatma Gandhi Road, Calcutta 700 1 009 in 1980; republished in a revised and updated edition by Zed lrr lr<lduction Books Ltd., 57 Caledonian Road, London Nl 9BU in 1984. I l'lrc Rural Scene I Copyright @ Sumanta Banerjee, 1980, 1984 I lrc Agrarian Situationt 1966-67 I 6 Typesetting by Folio Photosetting ( l'l(M-L) View of Indian Rural Society 7 Cover photo courtesy of Bejoy Sen Gupta I lrc Government's Measures Cover design by Jacque Solomons l lrc Rural Tradition: Myth or Reality? t2 Printed by The Pitman Press, Bath l't'lrstnt Revolts t4 All rights reserved llre Telengana Liberation Struggle 19 ( l'l(M-L) Programme for the Countryside 26 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Banerjee, Sumanta ' I'hc Urban Scene 3l India's simmering revolution. I lrc Few at the ToP JJ l. Naxalite Movement 34 I. Title I lro [ndustrial Recession: 1966-67 JIa- 322.4'z',0954 D5480.84 I lre Foreign Grip on the Indian Economy 42 rsBN 0-86232-038-0 Pb ( l'l(M-L) Views on the Indian Bourgeoisie ISBN 0-86232-037-2 Hb I lrc Petty Bourgeoisie 48 I lro Students 50 US Distributor 53 Biblio Distribution Center, 81 Adams Drive, Totowa, New Jersey l lrc Lumpenproletariat 0'1512 t lhe Communist Party 58 I lrc Communist Party of India: Before 1947 58 I lrc CPI: After 1947 6l I lre Inner-Party Struggle Over Telengana 64 I he CPI(M) 72 ( 'lraru Mazumdar's Theories 74 .l Nlxalbari 82 l'lre West Bengal United Front Government 82 Itcginnings at Naxalbari 84 Assessments Iconoclasm 178 The Consequences Attacks on the Police 182 Dissensions in the CPI(M) Building up the Arsenal 185 The Co-ordination Committee The Counter-Offensive 186 Jail Breaks 189 5.