Download Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celtic Newsletter – Fall 2016

ROANOKE CATHOLIC SCHOOL CELTIC NEWSLETTER FALL 2016 INSIDE: Back on “The Hill,” alumnus David Turk resurrects the Celtics volleyball program — winning games, fans and, most importantly, hearts MESSAGE FROM PRINCIPAL & HEAD OF SCHOOL Dear Alumni, School Families and Friends of Roanoke Catholic, I have an opportunity in this edition of our Celtic Newsletter to spotlight some wonderful “highlights” at Roanoke Catholic School. We have a tremendous volunteer base in our school community, but in all my years of service — from college and public school work to my partnership with Roanoke Catholic — I have never been so incredibly impressed with four parents who truly epitomize the servant’s heart and giving spirit of our faith. I must share with you how blessed we are to have: Regina Alouf, Ann PRINCIPAL & HEAD OF SCHOOL Kovats, Kristine Safford and Patrick Patterson Kim Yeaton within our ASSISTANT PRINCIPALS ranks. Julie Frost Christopher Michael These four moms — dubbed The Fabulous Four SCHOOL BOARD — have had their hands and Steve Nagy, Chair hearts in nearly every major John Thomas, Vice Chair Mike McEvoy, Treasurer (Finance) event designed to help Vicki Finnigan, Secretary improve the quality of our Home and School Association’s “Fab Four” (from left): Kim Yeaton, Ann Kovats, Regina Alouf, Kristine Safford ST. ANDREW’S school climate and Rev. Mark White community. Without ever asking, they are here to support our students, Rich Joachim (Strategic Planning) faculty, staff and families with their time, treasures and talents. OUR LADY OF NAZARETH Rev. Msgr. Joseph Lehman, Pastor Their commitment to RCS was exemplified, again, the morning of OUR LADY OF PERPETUAL HELP October 27 during the Junior Class Ring Ceremony. -

Papal Pilgrimages to Poland As Pedagogical Programs

PAPAL PILGRIMAGES TO POLAND AS PEDAGOGICAL PROGRAMS, 1979-1987 By Richard Nabozny Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Maciej Janowski Second Reader: Nadia Al-Bagdadi CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2012 CEU eTD Collection Copyright Notice Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. Abstract This thesis aims to reconstruct the speeches given by Pope John Paul II on his visits to Poland in 1979, 1983, and 1987 as part of a specially designed pedagogical program. The author argues that one of the functions of the papal visits, as a pedagogical program, was to provide instruction and establish a firm moral and cultural foundation for the people of communist Poland. That being said, this thesis also asserts that John Paul II viewed himself as a pedagogue to the nation. The author shows how the Pope’s intellectual development contributes to this position and examines his speeches in light of the situation in Poland before and after each visit. Quentin Skinner’s ideas on meaning and intention are used as the analytical apparatus for this thesis. By distinguishing between different forms of meaning and the intentions of speech, this thesis is able to argue that there are present different layers of meaning in the Pope’s speeches; of which one corresponds to the pedagogical programs. -

Liber Accusationis Secundus

LIBER ACCUSATIONIS SECUNDUS À notre Saint Père le pape Jean-Paul II, par la grâce de Dieu et la loi de l’Église, juge souverain de tous les fidèles du Christ, plainte pour HÉRÉSIE, SCHISME, SCANDALE, à l’encontre de notre frère dans la foi Karol Wojtyla par l’abbé Georges de Nantes Table des matières L’ACCUSATION ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. DE L A TRANSCENDANCE ET ROY AUT É DE L’HOMM E : V OTRE BLAS P HÈM E .............................................. 4 LE CHRISTIANISME N’EST PAS UNE POLITIQUE .............................................................................................................................. 5 LE CHRISTIANISME EST UN HUMANISME ....................................................................................................................................... 5 UN HUMANISME ET NON UNE RELIGION ....................................................................................................................................... 6 UN HUMANISME ET UNE SUBVERSION .......................................................................................................................................... 9 UN HUMANISME, UN LAÏCISME ................................................................................................................................................... 11 2. DE L A DIVI NIT É ET ROY AUT É DE JÉSUS -CHRIST : VOTRE APO STAS I E ..................................................... -

Assisted Suicide Law

EST IVER February is National Catholic Press Month W R Bishop’s Column, page 2 Care of Creation, pages 4- 6 Legislative Update, page 14 Diocesan Statement of Finance, pages 20-21 Informing Catholics in Western South Dakota since May 1973 Healthier Soil, Healthier Cattle, 5 Diocese of Rapid City CFebruaryatholic 2017 South Dakota Volume 45 Number 10 www.rapidcitydiocese.org Ash Wednesday, Addressing problems March 1 In Lent we are called to a conversion, a renewed sense in health laws of our frailty or sinfulness, as WASHINGTON — well as profound trust in the own rights in court.” new life that flows from the Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan and Cardinal Dolan and death and resurrection of Archbishop William E. Lori — Archbishop Lori recalled the Christ. This stained glass as chairmen of the U.S. Confer- Hippocratic oath’s rejection of window is from the Cathedral ence of Catholic Bishops’ abortion in the profession of of Our Lady of Perpetual Committee on Pro-Life Activi- medicine, indicating that the Act Help, Rapid City. For Lenten ties and Ad Hoc Committee for will benefit not only Catholic regulations and reconcilia- Religious Liberty, respectively — medical professionals but “the tions times see page 16. wrote to both Houses of the great majority of ob/gyns (who) Check with local parishes for United States Congress on Stations of the Cross dates remain unwilling to perform and times. (WRC photo) February 8, urging support for abortions.” the Conscience Protection Act of Finally, they explained that 2017 (H.R. 644, S. 301). conscience protection facilitates The Conscience Protection access to life-affirming health Act, they wrote, is “essential care: “When government .. -

A Short Introduction to the CWL My Name Is Father Michael Coyne

A Short Introduction to the CWL My name is Father Michael Coyne and I was ordained to the Priesthood on Sept 8th, 2020 by Bishop Guy Desrochers, and subsequently appointed to be the Pembroke Diocesan Spiritual Advisor to the Catholic Women’s League on the 17th of November 2020. I was born in North Bay in 1973. My parents were both Catholic, and I was baptised shortly after my birth, as was the Catholic tradition at the time. When I was six years old my family moved to Carleton Place and this is where I spent most of my formative early years growing up. My family eventually moved one final time back to Renfrew when my aunt, who lived in Renfrew, moved into the Quail Creek residence and we moved into my father’s ancestorial home on Barr Street. At this point in my life journey I began the discernment between two unique but complementary pursuits, the profession of teaching and the passion of missionary outreach. I started my spiritual journey by exploring the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, which is a missionary religious congregation in the Catholic Church. It was founded on January 25, 1816, by Saint Eugène de Mazenod, a French priest born in Aix-en- Provence in the south of France on August 1, 1782. The congregation was given recognition by Pope Leo XII on February 17, 1826. The congregation is composed of priests and brothers usually living in community. Oblate means a person dedicated to God or God’s service. As a young man, I joined what they would call their Novitiate year to discern a calling to this missionary faith community. -

The History of Editing Literary and Theatrical Works of Karol Wojtyła – John Paul II*

The Person and the Challenges Volume 9 (2019) Number 1, p. 127–153 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15633/pch.3366 Jacek Popiel ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8790-2757 Jagiellonian University, Poland The History of Editing Literary and Theatrical Works of Karol Wojtyła – John Paul II* Abstract The article is devoted to the history of the edition of literary and theater works of Karol Wojtyla – John Paul II. Based on the surviving materials in the archives, often unknown facts were presented showing the subsequent phases of discovery of Wojtyła as a poet, playwright, and actor. Keywords John Paul II, history of literature, poetry, drama, theatre. The editing of literary and theatrical works of Karol Wojtyła – John Paul II – is warranted by a conviction that you cannot fully understand the person of the Holy Father without an insight into this part of his biography that concerns his fascination with poetry, drama and theatre. Therefore, you need to refer to the sources: manuscripts and typescripts, Church and private archives, and to carry out a comparative study of the preserved materials. In the event of each researcher, such work is combined with the hope of managing to get to the * The text is an introduction to the book: Karol Wojtyła. Jan Paweł II, Dzieła literackie i teatralne. Tom I. Juwenilia (1938-1946), ed. Jacek Popiel, Kraków 2019. The Person and the Challenges 128 Volume 9 (2019) Number 1, p. 127–153 texts not known so far. Literature and theatre – these areas of creativity were close to Wojtyła since the times of attending the Wadowice high school. -

CATHERINE of GENOA-PURGATION and PURGATORY, the SPIRI TUAL DIALOGUE Translation and Notes by Serge Hughes Introduction by Benedict J

TI-ECLASSICS a:wESTEP.N SPIPlTUAIJTY i'lUBRi'lRY OF THEGREfiT SPIRITUi'lL Mi'lSTERS ··.. wbile otfui'ffKS h;·I�Jmas tJnd ;·oxiJ I:JOI'I!e be n plenli/111, books on \�stern mystics ucre-.trlfl o1re -bard /(I find'' ''Tbe Ptwlist Press hils just publisbed · an ambitious suies I hot sbu111d lnlp remedy this Jituation." Psychol�y li:x.Jay CATHERINE OF GENOA-PURGATION AND PURGATORY, THE SPIRI TUAL DIALOGUE translation and notes by Serge Hughes introduction by Benedict j. Grocschel. O.F.M. Cap. preface by Catherine de Hueck Doherty '.'-\1/tbat I /ltJt'e saki is notbinx Cllmf'dretltowbat lfeeluitbin• , t/Hu iJnesudwrresponden�.· :e /J/ hwe l�t•twec.'" Gtul and Jbe .\ou/; for u·ben Gfltlsees /be Srml pure llS it iJ in its orixins, lie Ill/(.� ,1( it ll'tlb ,, xlcmc.:c.•. drau·s it llrYIbitMIJ it to Himself u-ilh a fiery lfll•e u·hich by illt'lf cout.lunnibilult' tbe immorttJI SmJ/." Catherine of Genoa (}4-17-15101 Catherine, who lived for 60 years and died early in the 16th century. leads the modern reader directly to the more significant issues of the day. In her life she reconciled aspects of spirituality often seen to be either mutually exclusive or in conflict. This married lay woman was both a mystic and a humanitarian, a constant contemplative, yet daily immersed in the physical care of the sick and the destitute. For the last five centuries she has been the inspiration of such spiritual greats as Francis de Sales, Robert Bellarmine, Fenelon. Newman and Hecker. -

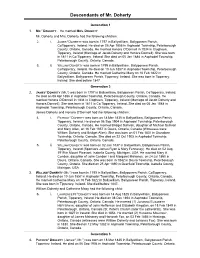

Descendants of Mr. Doherty

Descendants of Mr. Doherty Generation 1 1. MR.1 DOHERTY . He married MRS. DOHERTY. Mr. Doherty and Mrs. Doherty had the following children: 2. i. JAMES2 DOHERTY was born in 1797 in Ballywilliam, Ballyporeen Parish, CoTipperary, Ireland. He died on 08 Apr 1856 in Asphodel Township, Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. He married Honora O'Donnell in 1834 in Clogheen, Tipperary, Ireland (Marriage of Jacob Doherty and Honora Donnell). She was born in 1811 in Co Tipperary, Ireland. She died on 05 Jan 1888 in Asphodel Township, Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. 3. ii. WILLIAM DOHERTY was born in 1799 in Ballywilliam, Ballyporeen Parish, CoTipperary, Ireland. He died on 10 Jun 1857 in Asphodel Township, Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. He married Catherine Maxy on 16 Feb 1822 in Ballywilliam, Ballyporeen Parish, Tipperary, Ireland. She was born in Tipperary, Ireland. She died before 1847. Generation 2 2. JAMES2 DOHERTY (Mr.1) was born in 1797 in Ballywilliam, Ballyporeen Parish, CoTipperary, Ireland. He died on 08 Apr 1856 in Asphodel Township, Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. He married Honora O'Donnell in 1834 in Clogheen, Tipperary, Ireland (Marriage of Jacob Doherty and Honora Donnell). She was born in 1811 in Co Tipperary, Ireland. She died on 05 Jan 1888 in Asphodel Township, Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. James Doherty and Honora O'Donnell had the following children: 4. i. PATRICK3 DOHERTY was born on 18 Mar 1835 in Ballywilliam, Ballyporeen Parish, Tipperary, Ireland. He died on 06 Sep 1904 in Asphodel Township, Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. He married Bridget Sullivan, daughter of Michael Sullivan and Mary Allen, on 16 Feb 1857 in Douro, Ontario, Canada (Witnesses were William Doherty and Bridget Allen). -

Hostel at Whitehorse

'-l......· . <C 0 S~;~ o IX..... ;::) U.• [) t-t:)ON C [) O:U~...1 ... ;::)< ,...CI.)CZ:~ -...J .it Nationa' P .. ~ ,blOt:-cz: r the Indian6 of anada L.J .C. et M.l. zCZ:O"Z Single Copies 10 cents < LsJ ...... 0 ~ :& ~ :i==================================================== Vol. XXIII, No.8 )A OCTOBER 1960 Indian Hostel At Whitehorse WHITEHORSE, Yukon (CCC) - The lay apostles of the Madonna House Apostolate from Combermere, Ont., will blaze a new missionary trail into the far north for the second time in six years when they open on September 15 a large residential hostel here for Catholic Indian students. To be known as Our Lady of tourist attraction and the talk of Whitehorse, the new hostel is a the north because of the bril further implementation of the liant colors used for exterior mandate given to Madonna decoration. House in 1954 by Most Rev. J. N ext door to Our Lady of L. Coudert, O.M.I., Vicar Apos Whitehorse hostel, a new Catho tolic of Whitehorse, when Mary lic high school is under construc house was founded here to as tion where students of Grades 8, sist the Oblate missionaries in 9 and 10 will be enrolled. Catho their work with the Indians. lic students in grades 11 and 12 Built by the Canadian govern attend the Whitehorse high ment at a cost of more than school at present. $500,0'00, Our Lady of White horse hostel will accommodate Young Indians of the Yukon 100 students, in grades 7 to 12. are desperately in need of an Rev. -

The Rosary a Prayer for All Times

Issue No. 12 • May-June 2014 The Rosary A Prayer for All Times Cover Art: ‘Rosary Mother of God with Sts DominicSerra and Connects Francis of Assisi’ • May-June by Nicola Grassi,2014 c.17101 My Dear Fellow Serrans, Shalom! This year, we will be celebrating 50 years of Serra in Brazil. organizing such a memorable and meaningful convention Let us join our fellow Serrans from Brazil to thank our Lord for all of us. It has certainly set new standards in many for this great blessing. I remember the very warm hospitality aspects. They remain steadfast in trusting in the Lord to of the Serrans from Brazil at the National Shrine of Our pull them through despite the many personal trials and Lady of Aparecida when I visited them in November last challenges that each of them went through during the year. Our heartiest congratulations to Serrans in Brazil on months in the run-up to the convention. their golden jubilee celebrations! I personally believe that it is important for Serrans to make As May is the month of the Rosary of Our Blessed Mother, the effort to attend Serra conventions because it gives we have featured a very insightful article by the late Fr. John Serrans from different countries a platform to renew old Hardon on the Rosary – the indispensable prayer for all friendships and make new ones. We do not exist alone for Serrans. There is also an interesting true story on the three we are a global apostolate just as the Catholic Church is doves that are usually depicted at the feet of the statue of universal. -

1 the Female Genius, As St. John Paul II Developed It 4/15/18 Introduction Everyone Knows That God's Gifts to Women Exceed Ou

The Female Genius, as St. John Paul II Developed It 4/15/18 Introduction Everyone knows that God’s gifts to women exceed our understanding. But we observe that females use their ge- nius to care for the needy people. This is most obvious in baby-care. Males can’t begin to compete, because they lack the female genius that empowers women to nurse people, animals, even plants, into improved life. They help them flourish. One way to express this female genius is that women nurture life. They love to help life grow. This general de- scription is a good start. It distinguishes women’s specifically female gifts from a long list of their other gifts, like beauty, serenity, and superior coordination. Most women take these gifts for granted. They are too busy using them to talk about them. They act them out quite naturally. Women don’t wait for concepts or verbal description. What can words add to the unfolding of their genius in action? Most men stand in awe, struck dumb by the splendor of female gifts. But taking ladies for granted can degenerate into abuse of the gentler, weaker, woman. So notorious is man’s abuse of woman that for the past 50 years we have designated women a minority. By head-count women are the majority. But by dominance, their weakness resembles that of a numerical minority, overwhelmed by a majority. Abuse of women in his native Poland urges Karol Wojtyla to defend them. His philosophical analysis of women uncovers the female genius. Ready to defend Polish women against Communists, he surprises everyone by being elected Pope in October 1978. -

To Proclaim Christ and God's Kingdom Today

OUR MISSION TO PROCLAIM CHRIST AND ROMAN CATHOLIC DIOCESE OF GOD’S KINGDOM SASKATOON TODAY GOALS: “Have the same mind and heart as Christ Jesus” (Phil 2:5) Draw People into a Deepening Intimacy with the Lord! Supporting a deepening friendship and intimacy with Jesus Christ • Help people pray; and provide support and tools for growth in discipleship and holiness • Provide regular opportunities for gathered prayer, including Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament • Implement and strengthen evangelization programs in parishes and schools, emphasizing the Sacraments; the Sacred Scriptures; Life in the Church; Works of Mercy • Provide for more lay and clergy spiritual directors • Provide retreats and workshops for men, women, and youth addressing the art of accompaniment, to deepen their relationship with Christ Make Every Sunday Matter “Embrace Your Priesthood” Sunday celebrations Discerning God’s call to each person to share in the mission and life of the Lord • Effective preaching • Beautiful music: promote through training, • Equip and support Church members re: ways to provide workshops, performances ministry and service in our parish • Excellent liturgy: full and active participation! • Provide vocations support for priesthood, religious life, (see Sacrosanctum Concilium: #14) marriage, lay ministry leadership and service • Effective feedback from parishioners • Promote discipleship paths: Madonna House Apostolate; • Hospitality and welcoming NET Ministries; FacetoFace; Pure Witness Ministries; Catholic Christian Outreach (CCO); St. Therese