Open Walsh Thesis Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Post-Revolutionary South Carolina Legislation, 26 Vanderbilt Law Review 939 (1973) Available At

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 26 Issue 5 Issue 5 - October 1973 Article 2 10-1973 American Independence and the Law: A Study of Post- Revolutionary South Carolina Legislation James W. Ely, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation James W. Ely, Jr., American Independence and the Law: A Study of Post-Revolutionary South Carolina Legislation, 26 Vanderbilt Law Review 939 (1973) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol26/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. American Independence and the Law: A Study of Post-Revolutionary South Carolina Legislation James W. Ely, Jr.* Joseph Brevard, a South Carolina judge, observed in 1814 that "the laws of a country form the most instructive portion of its his- tory."' Certainly the successive printed collections of state statutes are among the most reliable and readily available sources for early American legal history.2 While statutes on their face do not reveal * Assistant Professor of Law, Vanderbilt University. Member, Bar of State of New York. A.B. 1959, Princeton University; LL.B. 1962, Harvard Law School; Ph.D. 1971, Univer- sity of Virginia. 1. 1 J. BREVARD, AN ALPHABETICAL DIGEST OF THE PUBLIC STATUTE LAW OF SOUTH CARO- LINA ix (1814). Brevard (1766-1821) served as a circuit court judge from 1801 to 1815 and thereafter spent 4 years as a member of Congress. -

1776, the Musical

For Immediate Release Date: August 31, 2016 Contact: Susan Davenport Director of Communications Virginia Repertory Theatre [email protected] 8047831688 ext 1133 8045138211 Mobile Virginia Repertory Theatre Opens the Signature Season with 1776, the Musical Starring Scott Wichmann as John Adams Richmond, VA Virginia Repertory Theatre announces the opening of 1776, The Musical, at the Sara Belle and Neil November Theatre, 114 West Broad Street on Friday, September 30, 2016 with two previews on September 28 and 29. The show runs through October 23, 2016. Often referred to as “America’s Musical,” 1776 is a lively, funny, and momentous story of the second Continental Congress and the writing of the Declaration of Independence. Peter Stone and Sherman Edwards wrote the musical in the years leading up to America’s bicentennial. It debuted on Broadway in 1969 and won the Tony Award for Best Musical. Virginia Rep will partner with the Virginia Historical Society to provide related talkbacks and discussions throughout the run of the show. Visit http://varep.org/_1776novembertheatrerichmond.html for details. Director Debra Clinton is thrilled to work with such an outstanding cast. “I see 1776 as an opportunity for people to revisit the history of our country and to reflect on what brings us together as Americans. It is a very uplifting story even in the context of hard compromise.” Clinton’s recent credits for Virginia Rep include The Whipping Man and the family smashhit Croaker: The Frog Prince Musical, which she cowrote with Jason Marks. Sandy Dacus will serve as music director. -

THE CORRESPONDENCE of ISAAC CRAIG DURING the WHISKEY REBELLION Edited by Kenneth A

"SUCH DISORDERS CAN ONLY BE CURED BY COPIOUS BLEEDINGS": THE CORRESPONDENCE OF ISAAC CRAIG DURING THE WHISKEY REBELLION Edited by Kenneth A. White of the surprisingly underutilized sources on the early history Oneof Pittsburgh is the Craig Papers. Acase inpoint is Isaac Craig's correspondence during the Whiskey Rebellion. Although some of his letters from that period have been published, 1 most have not. This omission is particularly curious, because only a few eyewitness ac- counts of the insurrection exist and most ofthose were written from an Antifederalist viewpoint. These letters have a value beyond the narration of events, how- ever. One of the questions debated by historians is why the federal government resorted to force to put down the insurrection. Many have blamed Alexander Hamilton for the action, attributing it to his per- sonal approach to problems or to his desire to strengthen the central government. 2 These critics tend to overlook one fact : government officials make decisions based not only on their personal philosophy but also on the facts available to them. As a federal officer on the scene, Craig provided Washington and his cabinet with their informa- Kenneth White received his B.A. and M.A.degrees from Duquesne Uni- versity. While working on his master's degree he completed internships with the Adams Papers and the Institute of Early American History and Culture. Mr. White is presently working as a fieldarchivist for the Pennsylvania His- torical and Museum Commission's County Records Survey and Planning Study.— Editor 1 Portions of this correspondence have been published. For example, all or parts of six of these letters appeared in Harold C. -

The Impact of Weather on Armies During the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Force of Nature: The Impact of Weather on Armies during the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T. Engel Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE FORCE OF NATURE: THE IMPACT OF WEATHER ON ARMIES DURING THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE, 1775-1781 By JONATHAN T. ENGEL A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Jonathan T. Engel defended on March 18, 2011. __________________________________ Sally Hadden Professor Directing Thesis __________________________________ Kristine Harper Committee Member __________________________________ James Jones Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii This thesis is dedicated to the glory of God, who made the world and all things in it, and whose word calms storms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Colonies may fight for political independence, but no human being can be truly independent, and I have benefitted tremendously from the support and aid of many people. My advisor, Professor Sally Hadden, has helped me understand the mysteries of graduate school, guided me through the process of earning an M.A., and offered valuable feedback as I worked on this project. I likewise thank Professors Kristine Harper and James Jones for serving on my committee and sharing their comments and insights. -

Essay Quiz Study Guide 1 Unit 1: Colonial America (Periods 2 & 3)

Essay Quiz Study Guide 1 Unit 1: Colonial America (Periods 2 & 3) Note: Some of the content carries over from chapter to chapter and you will need to use prior knowledge to fully answer some of the essay questions. Quiz 1.2 (Chapter 2 & 3) 1. Choose TWO of the following and analyze their impact on colonial North American development between 1620 and 1700. Puritanism The Enlightenment Plantation Agriculture 2. Analyze the role of trans-Atlantic trade and Great Britain’s mercantilist policies in the economic development of the British North American colonies in the period from 1650 to 1750. 3. Discuss the origins and development of slavery in Britain’s North American colonies. 4. Analyze how the actions taken by BOTH American Indians and European colonists shaped those relationships in THREE of the following regions during the period prior to 1700. New England Chesapeake New York New France 5. Evaluate the reasons British American colonists developed representative governments during the period of salutary neglect. Quiz 1.3 (Chapter 4) 1. Compare and contrast the British, French, and Spanish imperial goals in North America between 1580 and 1763. 2. Compare the ways in which the following reflected tensions in colonial society. Pueblo Revolt Bacon’s Rebellion Stono Rebellion 3. Compare and contrast the ways in which economic development affected politics in Massachusetts and Virginia in the period from 1607 to 1750. 4. Compare the ways in which religion shaped the development of colonial society (to 1740) in TWO of the following regions: New England Chesapeake Middle Atlantic 5. Evaluate the extent to which commercial exchange systems such as mercantilism and triangular trade fostered change in the British economy in the period from 1660 to 1763. -

Calendar of North Carolina Papers at London Board of Trade, 1729 - 177

ENGLISH RECORDS -1 CALENDAR OF NORTH CAROLINA PAPERS AT LONDON BOARD OF TRADE, 1729 - 177, Accession Information! Schedule Reference t NON! Arrangement t Chronological Finding Aid prepared bye John R. Woodard Jr. Date t December 12, 1962 This volume was the result of a resolution (N.C. Acts, 1826-27, p.85) pa~sed by the General Assembly of North Carolina, Febuary 9, 1821. This resolution proposed that the Governor of North Carolina apply to the British government for permission to secure copies of documents relating to the Co- lonial history of North Carolina. This application was submitted through the United states Ninister to the Court of St. James, Albert Gallatin. Gallatin vas giTen permission to secure copies of documents relating to the Colonial history of North Carolina. Gallatin found documents in the Board of Trade Office and the "state Paper uffice" (which was the common depository for the archives of the Home, Foreign, and Colonial departments) and made a list of them. Gallatin's list and letters from the Secretary of the Board of Trade and the Foreign Office were sent to Governor H.G. Burton, August 25, 1821 and then vere bound together to form this volume. A lottery to raise funds for the copying of the documents was authorized but failed. The only result 6"emS to have been for the State to have published, An Index to Colonial Docwnents Relative to North Carolina, 1843. [See Thornton, }1ary Lindsay, OffIcial Publications of 'l'heColony and State of North Carolina, 1749-1939. p.260j Indexes to documentS relative to North Carolina during the coloDl81 existence of said state, now on file in the offices of the Board of Trade and state paper offices in London, transmitted in 1827, by Mr. -

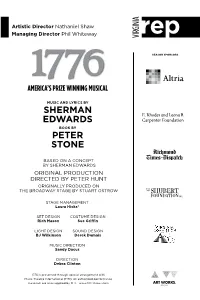

Sherman Edwards Peter Stone

Artistic Director Nathaniel Shaw Managing Director Phil Whiteway 1776 SEASON SPONSORS AMERICA’S PRIZE WINNING MUSICAL MUSIC AND LYRICS BY SHERMAN E. Rhodes and Leona B. EDWARDS Carpenter Foundation BOOK BY PETER STONE BASED ON A CONCEPT BY SHERMAN EDWARDS ORIGINAL PRODUCTION DIRECTED BY PETER HUNT ORIGINALLY PRODUCED ON THE BROADWAY STAGE BY STUART OSTROW STAGE MANAGEMENT Laura Hicks* SET DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN Rich Mason Sue Griffin LIGHT DESIGN SOUND DESIGN BJ Wilkinson Derek Dumais MUSIC DIRECTION Sandy Dacus DIRECTION Debra Clinton 1776 is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com CAST MUSICAL NUMBERS AND SCENES ACT I MEMBERS OF THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS For God’s Sake, John, Sit Down ............................... Adams & The Congress Piddle, Twiddle ............................................................. Adams President Delaware Till Then .......................................................... Adams & Abigail John Hancock............ Michael Hawke Caesar Rodney ........... Neil Sonenklar The Lees of Old Virginia ......................................Lee, Franklin & Adams Thomas McKean ..... Andrew C. Boothby New Hampshire But, Mr. Adams — .................. Adams, Franklin, Jefferson, Sherman & Livingston George Read ................ John Winn Dr. Josiah Bartlett ......Joseph Bromfield Yours, Yours, Yours ................................................ Adams & Abigail Maryland He Plays the Violin ........................................Martha, -

Declaration of Independence

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776 —————————— THE UNANIMOUS DECLARATION OF THE THIRTEEN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation. We hold these truths to be self-evident—that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that, to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate, that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shown, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government and to provide new guards for their future security. -

Southern Music and the Seamier Side of the Rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Folklore Commons, Music Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hutson, Cecil Kirk, "The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10912. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthiough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

The Faulkner Murals: Depicting the Creation of a Nation

DEPICTING the CREATION of a NATION The Story Behind the Murals About Our Founding Documents by LESTER S. GORELIC wo large oil-on-canvas murals (each about 14 feet by 37.5 feet) decorate the walls of the Rotunda of the National T Archives in Washington, D.C. The murals depict pivotal moments in American history represented by two founding doc uments: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. In one mural, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia is depicted handing over his careful ly worded and carefully edited draft of the Declaration of Independence to John Hancock of Massachusetts. Many of the other Founding Fathers look on, some fully supportive, some apprehensive. In the other, James Madison of Virginia is depicted presenting his draft of the Constitution to fellow Virginian George Washington, president of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, and to other members of the Convention. Although these moments occurred in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia (Independence Hall)—not in the sylvan settings shown in the murals—the two price less documents are now in the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., and have been seen by millions of visitors over the years. When the National Archives Building was built in the Jefferson’s placement at the front of the Committee of mid-1930s, however, these two founding documents were Five reflects his position as its head. Although Jefferson was in the custody of the Library of Congress and would not the primary author of the Declaration, his initial draft was be transferred to the Archives until 1952. Even so, the ar edited first by Adams and then by Franklin. -

The North Carolina Booklet

cJ(A^^^jr Vol. VIII. JULY, 1908. No. 1 13he floRTH CflROIilNfl BoOKliET ' ' Caroli7ia ! Carolina ! Heaven'' s blessings attend her ! WJiile we live we will cherish, protect and defend her.'''' Published by THE NORTH CAROLINA SOCIETY DAUGHTERS OF THE REVOLUTION The object of the Booklet is to aid in developing amd preserving Korth Carolina History. The proceeds arising from its publication will be devoted to patriotic purposes. Editoes. : : : ADVISORY BOARD OF THE NORTH CAROLINA BOOKLET. Mrs. Spiek Whitakeb. Mes. T. K. Beuner. Professor D. H. Hill. Mb. R. D. W. Connou. Mb. W. J. Peele. De. E. W. Sikes. Professor E. P. Moses. Db. Richard Dillabd. De. Kemp P. Battle. Me. James Sprunt. Me. Marshall DeLancey Haywood. Judge Walter Clabk. EDITORS : Miss Mary Hilliaed Hinton, Mes. E E. Moffitt. OFFICERS OF THE NORTH CAROLINA SOCIETY DAUGHTERS OF THE REVOLUTION, 1906-1908. regent : mbs. e. e. moffitt. VICE-BEGENT : Mrs. WALTER CLARK. honorary REGENT: Mrs. SPIER WHITAKER. RECORDING SECRETARY: Mrs. LEIGH SKINNER. COREESPONDING SECEETAEY Mes. W. H. PACE. TEEASUREE Mes. frank SHERWOOD. EEGISTEAE: Miss MARY BILLIARD HINTON. GENEALOGIST Mbs. HELEN De BERNIERE WILLS. FOUNDEB OF THE NOETH CAROLINA SOCIETY AND ReGEINT 1896-1902: Mbs. spier WHITAKER. eegent 1902: Mbs. D. H. HILL, Sb.* eegent 1902-1906: Mrs. THOMAS K. BRUNER. * Died December 12, 1904. THE NORTH CAROLINA BOOKLET. Vol. VIII JULY, 1908 No. 1 JOHN HARVEY/ BY R. D. W. CONNOR, Secretary of the North. Carolina Historical Comm ission Of all the men who inaugurated the Revolution in JSTorth Carolina, John Harvey, perhaps, is least known. But little has been written of his services to his country, and the stu- dent of his career will search in vain outside of the bald offi- cial records for more than a mere mention of the official posi- tions which he held. -

Founding Principles Report

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION MOLLY M. SPEARMAN STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF EDUCATION Founding Principles Report Provided to the Senate Education Committee and the House Education and Public Works Committee Pursuant to S.C. Code § 59-25-155 October 15, 2017 The South Carolina Department of Education does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, veteran status, or disability in admission to, treatment in, or employment in its programs and activities. Inquiries regarding the nondiscrimination policies should be made to the Employee Relations Manager, 1429 Senate Street, Columbia, South Carolina 29201, 803-734-8781. For further information on federal non- discrimination regulations, including Title IX, contact the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights at [email protected] or call 1-800-421-3481. Contents Report Requirements ...................................................................................................................1 Summary of Founding Principles in South Carolina Standards ....................................................1 Professional Learning for Teachers .............................................................................................1 Next Steps ...................................................................................................................................3 Appendix A: South Carolina Standards Related to Founding Principles.......................................4 Kindergarten ...........................................................................................................................4