The Designation of the Pope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ostrogothic Papacy - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Ostrogothic Papacy - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ostrogothic_Papacy&printab... Ostrogothic Papacy From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Ostrogothic Papacy was a period from 493 to 537 where the papacy was strongly influenced by the Ostrogothic Kingdom, if the pope was not outright appointed by the Ostrogothic King. The selection and administration of popes during this period was strongly influenced by Theodoric the Great and his successors Athalaric and Theodahad. This period terminated with Justinian I's (re)conquest of Rome during the Gothic War (535–554), inaugurating the Byzantine Papacy (537-752). According to Howorth, "while they were not much interfered with in their administrative work, so long as they did not themselves interfere with politics, the Gothic kings meddled considerably in the selection of the new popes and largely dominated their election. Simony prevailed to a scandalous extent, as did intrigues of a discreditable kind, and the quality and endowments of the candidates became of secondary importance in their chances of being elected, compared with their skill in corrupting the officials of the foreign kings and in their powers of chicane."[1] According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, "[Theodoric] was tolerant towards the Catholic Church and did not interfere in dogmatic Pope Symmachus's (498-514) matters. He remained as neutral as possible towards the pope, though he triumph over Antipope Laurentius is exercised a preponderant influence in the affairs of the papacy."[2] -

Poverty, Charity and the Papacy in The

TRICLINIUM PAUPERUM: POVERTY, CHARITY AND THE PAPACY IN THE TIME OF GREGORY THE GREAT AN ABSTRACT SUBMITTED ON THE FIFTEENTH DAY OF MARCH, 2013 TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOL OF LIBERAL ARTS OF TULANE UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ___________________________ Miles Doleac APPROVED: ________________________ Dennis P. Kehoe, Ph.D. Co-Director ________________________ F. Thomas Luongo, Ph.D. Co-Director ________________________ Thomas D. Frazel, Ph.D AN ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the role of Gregory I (r. 590-604 CE) in developing permanent ecclesiastical institutions under the authority of the Bishop of Rome to feed and serve the poor and the socio-political world in which he did so. Gregory’s work was part culmination of pre-existing practice, part innovation. I contend that Gregory transformed fading, ancient institutions and ideas—the Imperial annona, the monastic soup kitchen-hospice or xenodochium, Christianity’s “collection for the saints,” Christian caritas more generally and Greco-Roman euergetism—into something distinctly ecclesiastical, indeed “papal.” Although Gregory has long been closely associated with charity, few have attempted to unpack in any systematic way what Gregorian charity might have looked like in practical application and what impact it had on the Roman Church and the Roman people. I believe that we can see the contours of Gregory’s initiatives at work and, at least, the faint framework of an organized system of ecclesiastical charity that would emerge in clearer relief in the eighth and ninth centuries under Hadrian I (r. 772-795) and Leo III (r. -

Journeys to Byzantium? Roman Senators Between Rome and Constantinople

Journeys to Byzantium? Roman Senators Between Rome and Constantinople Master’s Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael Anthony Carrozzo, B.A Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Thesis Committee: Kristina Sessa, Advisor Timothy Gregory Anthony Kaldellis Copyright by Michael Anthony Carrozzo 2010 Abstract For over a thousand years, the members of the Roman senatorial aristocracy played a pivotal role in the political and social life of the Roman state. Despite being eclipsed by the power of the emperors in the first century BC, the men who made up this order continued to act as the keepers of Roman civilization for the next four hundred years, maintaining their traditions even beyond the disappearance of an emperor in the West. Despite their longevity, the members of the senatorial aristocracy faced an existential crisis following the Ostrogothic conquest of the Italian peninsula, when the forces of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I invaded their homeland to contest its ownership. Considering the role they played in the later Roman Empire, the disappearance of the Roman senatorial aristocracy following this conflict is a seminal event in the history of Italy and Western Europe, as well as Late Antiquity. Two explanations have been offered to explain the subsequent disappearance of the Roman senatorial aristocracy. The first involves a series of migrations, beginning before the Gothic War, from Italy to Constantinople, in which members of this body abandoned their homes and settled in the eastern capital. -

Collectio Avellana and Its Revivals

The Collectio Avellana and Its Revivals The Collectio Avellana and Its Revivals Edited by Rita Lizzi Testa and Giulia Marconi The Collectio Avellana and Its Revivals Edited by Rita Lizzi Testa and Giulia Marconi This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Rita Lizzi Testa, Giulia Marconi and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-2150-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-2150-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. viii Rita Lizzi Testa I. The Collectio Avellana and Its Materials Chapter One ............................................................................................................... 2 The Power and the Doctrine from Gelasius to Vigile Guido Clemente Chapter Two............................................................................................................. 13 The Collectio Avellana—Collecting Letters with a Reason? Alexander W.H. Evers Chapter Three ......................................................................................................... -

Altars Personified: the Cult of the Saints and the Chapel System in Pope Pascal I's S. Prassede (817-819) Judson J

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Faculty Publications and Research Pomona Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2005 Altars personified: the cult of the saints and the chapel system in Pope Pascal I's S. Prassede (817-819) Judson J. Emerick Pomona College Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis Recommended Citation "Altars Personified: The ultC of the Saints and the Chapel System in Pope Pascal I's S. Prassede (817-819)" in Archaelogy in Architecture: Studies in Honor of Cecil L. Striker, ed. J. Emerick and D. Deliyannis (Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 2005), pp. 43-63. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Faculty Publications and Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Archaeology in Architecture: Studies in Honor of Cecil L. Striker Edited by Judson J. Em erick and Deborah M. Deliyannis VERLAG PHILIPP VON ZABERN . MAINZ AM RHEIN VII, 216 pages with 146 black and white illustrations and 19 color illustrations Published with the assistance of a grant from the James and Nan Farquhar History of An Fund at the University of Pennsylvania Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliotbek Die Deutsche Bibliorhek lists this publication in the Deutsche NationalbibJ iographie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at dJttp://dnb.ddb.de> . © 2005 by Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Maim am Rhein ISBN- I0: 3-8053-3492-3 ISBN- 13: 978-3-8053-3492-1 Design: Ragnar Schon, Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Maim All rights reserved. -

The Life of Saint Bernard De Clairvaux

The Life of Saint Bernard de Clairvaux Born in 1090, at Fontaines, near Dijon, France; died at Clairvaux, 21 August, 1153. His parents were Tescelin, lord of Fontaines, and Aleth of Montbard, both belonging to the highest nobility of Burgundy. Bernard, the third of a family of seven children, six of whom were sons, was educated with particular care, because, while yet unborn, a devout man had foretold his great destiny. At the age of nine years, Bernard was sent to a much renowned school at Chatillon-sur-Seine, kept by the secular canons of Saint-Vorles. He had a great taste for literature and devoted himself for some time to poetry. His success in his studies won the admiration of his masters, and his growth in virtue was no less marked. Bernard's great desire was to excel in literature in order to take up the study of Sacred Scripture, which later on became, as it were, his own tongue. "Piety was his all," says Bossuet. He had a special devotion to the Blessed Virgin, and there is no one who speaks more sublimely of the Queen of Heaven. Bernard was scarcely nineteen years of age when his mother died. During his youth, he did not escape trying temptations, but his virtue triumphed over them, in many instances in a heroic manner, and from this time he thought of retiring from the world and living a life of solitude and prayer. St. Robert, Abbot of Molesmes, had founded, in 1098, the monastery of Cîteaux, about four leagues from Dijon, with the purpose of restoring the Rule of St. -

The Guilt of Boethius

The Guilt of Boethius Nathan Basik Copyright © 2000 by Nathan Basik. All rights reserved. This document may be copied and circu- lated freely, in printed or digital form, provided only that this notice of copyright is included on all pages copied. 2 Introduction In the nineteenth century, Benjamin Jowett spent over thirty years translat- ing Plato’s Republic. That is an extreme example of perfectionism, but it helps us appreciate the magnitude (and the hubris) of the goal Boethius set for himself in the Introduction to his translation of Aristotle’s De Interpretatione: translating, analyzing, and reconciling the complete opera of Plato and Aristotle.1 As “incom- parably the greatest scholar and intellect of his day,”2 Boethius may have had the ability and the energy his ambition required. But we will never know how much Boethius would have achieved as a philosopher if he had not suffered a premature death. In 523, less than a year after being named Magister Officiorum3 by King Theodoric, Boethius was charged with treason, hastily and possibly illegally tried, and executed in 526.4 Since the contemporary sources of information about the affair are vague and fragmented, the passage of nearly 1500 years has brought no consensus in explaining Boethius’ tragic fall from a brilliant intellectual and political career. Though disagreement still shrouds the details of every aspect of the case, from indictment to execution, I will argue that Theodoric was fully justified in perceiving Boethius as a traitor. Claims that age or emotional passion or military pressures diminished the King’s judgment are, in this instance, unacceptable. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Case: 20-56156, 06/21/2021, ID: 12149429, DktEntry: 33, Page 1 of 35 No. 20-56156 United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit JOANNA MAXON et al., Plaintiffs/Appellants, v. FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, et al., Defendants/Appellees. Appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California | No. 2:19-cv-09969 (Hon. Consuelo B. Marshall) ____________________________________________ BRIEF OF PROFESSORS ELIZABETH A. CLARK, ROBERT F. COCHRAN, TERESA S. COLLETT, CARL H. ESBECK, DAVID F. FORTE, RICHARD W. GARNETT, DOUGLAS LAYCOCK, MICHAEL P. MORELAND, AND ROBERT J. PUSHAW AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES ____________________________________________ C. Boyden Gray Jonathan Berry Michael Buschbacher* T. Elliot Gaiser BOYDEN GRAY & ASSOCIATES 801 17th Street NW, Suite 350 Washington, DC 20006 202-955-0620 [email protected] * Counsel of Record (application for admission pending) Case: 20-56156, 06/21/2021, ID: 12149429, DktEntry: 33, Page 2 of 35 CERTIFICATE OF INTEREST Pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 26.1, counsel for amici hereby certifies that amici are not corporations, and that no disclosure statement is therefore required. See Fed. R. App. P. 29(a)(4)(A). Dated: June 21, 2021 s/ Michael Buschbacher i Case: 20-56156, 06/21/2021, ID: 12149429, DktEntry: 33, Page 3 of 35 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................ ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ............................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ................... 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................................................... 6 I. THE PRINCIPLE OF CHURCH AUTONOMY IS DEEPLY ROOTED IN THE ANGLO-AMERICAN LEGAL TRADITION. ................................................ 6 II. THE FIRST AMENDMENT PROHIBITS GOVERNMENT INTRUSION INTO THE TRAINING OF SEMINARY STUDENTS. -

The Małopolska Way of St James (Sandomierz–Więcławice Stare– Cracow–Szczyrk) Guide Book

THE BROTHERHOOD OF ST JAMES IN WIĘCŁAWICE STARE THE MAŁOPOLSKA WAY OF ST JAMES (SANDOMIERZ–WIĘCŁAWICE STARE– CRACOW–SZCZYRK) GUIDE BOOK Kazimiera Orzechowska-Kowalska Franciszek Mróz Cracow 2016 1 The founding of the pilgrimage centre in Santiago de Compostela ‘The Lord had said to Abram, “Go from your country, your people and your father’s household to the land I will show you”’ (Gen 12:1). And just like Abraham, every Christian who is a guest in this land journeys throughout his life towards God in ‘Heavenly Jerusalem’. The tradition of going on pilgrimages is part of a European cultural heritage inseparably connected with the Christian religion and particular holy places: Jerusalem, Rome, and Santiago de Compostela, where the relics of St James the Greater are worshipped. The Way of St James began almost two thousand years ago on the banks of the Sea of Galilee (Lake Tiberias). As Jesus was walking beside the Sea of Galilee, he saw two brothers, Simon called Peter and his brother Andrew. They were casting a net into the lake, for they were fishermen. ‘Come, follow me,’ Jesus said, ‘and I will send you out to fish for people’. At once they left their nets and followed him. Going on from there, he saw two other brothers, James son of Zebedee and his brother John. They were in a boat with their father Zebedee, preparing their nets. Jesus called them, and immediately they left the boat and their father and followed him. (Matthew 4:18‒22) Mortal St James The painting in Basilica in Pelplin 2 The path of James the Apostle with Jesus began at that point. -

Daily Saints – 1 March St. David of Wales Born: 500 AD, Caerfai Bay

Daily Saints – 1 March St. David of Wales Born: 500 AD, Caerfai Bay, United Kingdom, Died: March 1, 589 AD, St David’s, United Kingdom, Feast: 1 March, Canonized: 1123, Rome, Holy Roman Empire (officially recognized) by Pope Callixtus II, Venerated in Roman Catholic Church; Eastern Orthodox Church; Anglican Communion, Attributes: Bishop with a dove, usually on his shoulder, sometimes standing; on a raised hillock Among Welsh Catholics, as well as those in England, March 1 is the liturgical celebration of Saint David of Wales. St. David is the patron of the Welsh people, remembered as a missionary bishop and the founder of many monasteries during the sixth century. David was a popular namesake for churches in Wales before the Anglican schism, and his feast day is still an important religious and civic observance. Although Pope Benedict XVI did not visit Wales during his 2010 trip to the U.K., he blessed a mosaic icon of its patron, and delivered remarks praising St. David as “one of the great saints of the sixth century, that golden age of saints and missionaries in these isles, and...thus a founder of the Christian culture which lies at the root of modern Europe.” In his comments, Pope Benedict recalled the saint's dying words to his monastic brethren: "Be joyful, keep the faith, and do the little things." He urged that St. David's message, "in all its simplicity and richness, continue to resound in Wales today, drawing the hearts of its people to a renewed love for Christ and his Church." From a purely historical standpoint, little is known of David’s life, with the earliest biography dating from centuries after his time. -

Summer-Fall Newsletter

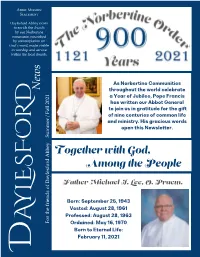

Abbey Mission Statement Daylesford Abbey exists to enrich the church by our Norbertine communio, nourished by contemplation on God’s word, made visible in worship and service within the local church. As Norbertine Communities News throughout the world celebrate a Year of Jubilee, Pope Francis D has written our Abbot General to join us in gratitude for the gift of nine centuries of common life and ministry. His gracious words open this Newsletter. Together with God, Among the People Father Michael J. Lee, O. Praem. Born: September 25, 1943 Vested: August 28, 1961 Professed: August 28, 1963 AYLESFOR For the friends of Daylesford Abbey Summer / Fall 2021 Ordained: May 16, 1970 Born to Eternal Life: February 11, 2021 D Contents 1. A Letter from the Abbot A Letter From the Abbot by Abbot Domenic A. Rossi, O. Praem. Words from Pope Francis 2. Words from Pope Francis For a number of years now, the Abbey has had two fig trees nestled in an 4. In Memoriam: outside area of one of our gardens, Fr. Michael Lee, O. Praem. well protected from winter winds. by Joseph McLaughlin, O. Praem. We would typically get at most, a few 5. Norbertine Farewell dozen figs and only at the very end to Saint Gabriel Parish of the summer. This year, however, was very different. by Francis X. Cortese, O. Praem. On just one of the fig trees, as soon as the leaves were starting to appear this spring, there also appeared dozens 7. Development Corner and dozens of figs(I counted 72). Moreover, the fruit were by John J. -

An Axiomatic Analysis of the Papal Conclave

Economic Theory https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-019-01180-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE An axiomatic analysis of the papal conclave Andrew Mackenzie1 Received: 26 January 2018 / Accepted: 12 February 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract In the Roman Catholic Church, the pope is elected by the (cardinal) electors through “scrutiny,” where each elector casts an anonymous nomination. Using historical doc- uments, we argue that a guiding principle for the church has been the protection of electors from the temptation to defy God through dishonest nomination. Based on axiomatic analysis involving this principle, we recommend that the church overturn the changes of Pope Pius XII to reinstate the scrutiny of Pope Gregory XV, and argue that randomization in the case of deadlock merits consideration. Keywords Pope · Conclave · Mechanism design · Impartiality JEL Classification Z12 · K16 · D82 · D71 1 Introduction Dominentur nobis regulae, non regulis dominemur: simus subjecti canonibus, cum canonum praecepta servamus.1 1 Quoted from the epistle of Pope Celestine I to the bishops of Illyricum (Pope Celestine I 428). My translation: “The rules should govern us, not the other way around: we should be submitted to the canons while we safeguard their principles.” I thank Corina Boar, Olga Gorelkina, Joseph Kaboski, Narayana Kocherlakota, Rida Laraki, Hervé Moulin, Romans Pancs, Marcus Pivato, Debraj Ray, Alvin Roth, Arunava Sen, Christian Trudeau, Rodrigo Velez, and two anonymous referees; seminar audiences at University of Windsor, University of Glasgow, the 2016 Meeting of the Society for Social Choice and Welfare, the 2017 D-TEA (Decision: Theory, Experiments and Applications) Workshop, and the 2018 Annual Congress of the European Economic Association; and especially William Thomson.