Development Plat Submittal Requirements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landmark Designation Report

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Department Planning and Development LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: James L. Autry House AGENDA ITEM: IV.d OWNERS: W. Murray Air and Mary B. Air HPO FILE NO: 09L217 APPLICANTS: Same DATE ACCEPTED: Mar-26-09 LOCATION: 5 Courtlandt Place – Courtlandt Place Historic District HAHC HEARING: May-21-09 30-DAY HEARING NOTICE: N/A PC HEARING: May-28-09 SITE INFORMATION The East 50 feet of Lot 23 and West 75 feet of Lot 24, Courtlandt Place subdivision, City of Houston, Harris County, Texas. The site includes a wood-frame and brick two-story residence. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark Designation HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY The James L. Autry House was designed by Sanguinet and Staats in 1912. It is an excellent example of Neo-Classical Revival architecture and reflects the elegance and architectural quality common along Courtlandt Place, one of Houston's earliest and most exclusive subdivisions. Established in 1906, Courtlandt Place, a tree-lined, divided boulevard, has maintained its residential integrity despite surrounding commercialism in adjacent blocks, and is designated as both a City of Houston and National Register historic district. James Lockhart Autry was a significant figure in the early days of the Texas oil industry. As an attorney and judge, Autry was a pioneer in the field of oil and gas law. After the discovery of the Spindletop oil field in 1901, Autry helped Joseph Cullinan organize the Texas Fuel Company, now known as Texaco. In partnership with Cullinan and Will Hogg, Autry later formed several other oil companies. -

Harry Clay Hanszen Ca.1950

Bibliography Primary Sources: The City of Houston. Timeline of Harry Clay Hanszen ca.1950. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. Hanszen, Alice. Alice Hanszen to J. T. McCants, April 5, 1955. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. * Harry C. Hanszen Next of Kin. ca.1950. Document. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. Harry Clay Hanszen ca.1950. Document. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. The Houston Chronicles. “H.C. Hanszen Chosen To Head Of Rice Board.” January 15, 1946. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. * The Houston Chronicle. “Harry C. Hanszen, Houston Oilman, Dies in Kerrville”, 1950, "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. * The Houston Chronicle. “Harry C. Hanszen Named Trustee by Rice Institute”, May 7, 1942. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. The Houston Press. “Harry C. Hanszen Elected As Chairman Of Rice Board.” January 15, 1946. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. -

Seagate Crystal Reports

HOUSTON PLANNING COMMISSION AGENDA NOVEMBER 20, 2008 CITY COUNCIL CHAMBER CITY HALL ANNEX 2:30 P.M. PLANNING COMMISSION MEMBERS Carol Lewis, Ph. D., Chair Mark A. Kilkenny, Vice Chair John W. H. Chiang David Collins Kay Crooker Sonny Garza James R. Jard D. Fred Martinez Robin Reed Richard A. Rice David Robinson Jeff Ross Lee Schlanger Algenita Scott Segars Talmadge Sharp, Sr. Jon Strange Beth Wolff Shaukat Zakaria The Honorable Grady Prestage, P. E., Fort Bend County The Honorable Ed Emmett, Harris County The Honorable Ed Chance, Montgomery County ALTERNATE MEMBERS D. Jesse Hegemier, P. E., Fort Bend County Mark J. Mooney, P. E., Montgomery County Jackie L. Freeman, P. E., Harris County EXOFFICIO MEMBERS M. Marvin Katz Mike Marcotte, P.E. Dawn Ullrich Frank Wilson SECRETARY Marlene L. Gafrick Meeting Policies and Regulations that an issue has been sufficiently discussed and additional speakers are repetitive. Order of Agenda 11. The Commission reserves the right to stop Planning Commission may alter the order of the speakers who are unruly or abusive. agenda to consider variances first, followed by replats requiring a public hearing second and consent agenda Limitations on the Authority of the Planning last. Any contested consent item will be moved to the Commission end of the agenda. By law, the Commission is required to approve Public Participation subdivision and development plats that meet the requirements of Chapter 42 of the Code of Ordinances The public is encouraged to take an active interest in of the City of Houston. The Commission cannot matters that come before the Planning Commission. -

Apr/May/Jun 2015

Texas Institute of Letters April/May/June 2015 Texas Institute of Letters website: http://www.texasinstituteofletters.org/ Nan Cuba and Kathleen Winter Are Chosen Dobie Paisano Fellowships Winners Named Winners of the Dobie Paisano Writing Fellowships for 2015 are Nana Cuba and Kathleen Winter. The fellowships, sponsored by The University of Texas at Austin and the Texas Institute of Letters, allow writers to live and work at the Paisano ranch, J. Frank Dobie’s 254-acre retreat west of Austin. Nan Cuba, recipient of the Jesse Jones Fellowship, is the author of Body and Bread (Engine Books, 2013), winner of the PEN Southwest Award in Fiction and the Texas Institute of Letters Steven Turner Award for Best Work of First Fiction; it was also listed as one of “Ten Titles to Pick Up Now” in O, Oprah’s Magazine, was a “Summer Books” choice from Huffington Post, and the San Antonio Express-News called it one of the “Best Books of 2013.” Cuba co-edited Art at our Doorstep: San Antonio Writers and Artists (Trinity University Press, 2008), and published other work in such places as Antioch Review, Harvard Review, Columbia, and Chicago Tribune’s Printer’s Row. Her story, “Watching Alice Watch,” was one 1 of the Million Writers Award Notable Stories (storySouth), and “When Horses Fly” won the George Nixon Creative Writing Award for Best Prose from the Conference of College Teachers of English. As an investigative journalist, she reported on the causes of extraordinary violence in LIFE, Third Coast, and D Magazine. She received an artist residency at Fundación Valparaiso in Spain and was a finalist for the Humanities Texas Award for Individual Achievement. -

Newsfromfondren

Volume 17, Number 1 Fall 2007 NEWS from FONDREN A LIBRARY NEWSLETTER TO THE RICE UNIVERSITY COMMUNITY Historic Treasures Emerge from Gym Daniel Webster once said, “What and brittle with age, had been stored is valuable is not new…” (Speech in the original field house and moved at Marshfield, Sept. 1, 1848). In the to the new gymnasium around 1950. Woodson Research Center, we are The locations of the discoveries, learning afresh the truth of that state- under the bleachers and in obscure ment as Rice’s rich historical record rooms at the very top of Autry in athletics slowly emerges through Court, suggest a reluctance to throw old, dirty, dusty, oftimes crumbling anything away. One room was above materials recently found in the the restrooms in the stadium, acces- recesses of the gymnasium. sible only by ladder. It took a lot of As renovation plans for the effort to get those boxes into such an athletic facility were finalized, staff out-of-the-way place. Artifacts found realized the need to retain valuable in various offices were likely kept for materials documenting Rice’s athlet- sentimental value or artistic form — ics programs through the years. Uni- trophies dating to 1915, a stuffed owl, versity historian Melissa Kean and a Rice owl decanter. university archivist Lee Pecht devised Responsibility for retaining and implemented a plan to transfer as written records mandated that certain many of the “finds” as possible to the files about sports programs be kept. Woodson Research Center. While However, over time staff retired or Dr. Kean conferred with athletics left Rice, records were inherited and staff to determine priorities and then interrelated files became separated. -

BRAZORIA COUNTY HISTORICAL MUSEUM Collections Reflect the Musical and Cultural Development of Houston Through Departmental

ABOUT ARCHIVISTS OF THE HOUSTON AREA! THE AFRICAN AMERICAN LIBRARY AT THE GREGORY SCHOOL, HOUSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY HARRIS COUNTY ARCHIVES HOUSTON GRAND OPERA ARCHIVES AND RESEARCH CENTER Archivists of the Houston Area (AHA!) was founded in 1998 by four local archivists to 1300 Victor Street, Freedmen’s Town, Houston, TX 77019 11525 Todd Street, Suite 300, Houston, TX 77055 510 Preston Street, Houston, TX 77002 facilitate interaction among area archivists and repositories. AHA! exists to increase 832/393-1440 http://www.thegregoryschool.org 713/274-9683 www.harriscountytx.gov/archives 713/228-0238 www.houstongrandopera.org/archives contact and communication among archivists and those working with records, to Monday-Thursday, 10am-6pm and Saturday, 10am-5pm By appointment only Monday-Friday, 9am-4:30pm, by appointment only provide opportunities for professional development, and to promote archival The collection documents the experience of African American residents, businesses, institutions The County Archives documents the history of the government and the citizens of Harris County The Archives maintains a large collection of material related to the history of the Houston Grand repositories and activities in the greater Houston, Texas area. It fulfills its mission by: and neighborhoods throughout Houston and the surrounding region. as revealed through the county records and donated materials. Opera. Conducting quarterly meetings with programs on archival topics BAYLOR COLLEGE OF MEDICINE ARCHIVES HOUSTON METROPOLITAN RESEARCH CENTER, HOUSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY Planning and promoting Archives Month 713/798-4501 www.bcm.edu Julia Ideson Building, 500 McKinney St., Houston, TX 77002 Providing professional development classes Currently a closed archive. Please call for further information. -

Cornerstone, Newsletter of the Rice Historical Society

[ The Woodson Research Center, An Introduction This issue of ,he Commtont will highlight some of the educational and historical resources co be found in the Woodson Research Cenccr (WRC). The Woodson is well known locally and regionally for its scop< of collections, its atcenrion to detailed finding aids. rhe ability to process collections quickly, personal attention to research needs and ease of acccssibiliry to the materials. The coupling of primary and secondary resource materials along with expertise with the coHections and a learning atmosphere are hallmarks of the Center. In the following articles written by Lee Pecht, Universiry Archivist and Director of Special Collections, and by the following individuals noted in the byline you can learn some of the riches to be- found in Rice's diverse collection. Contributors to chis introduction to the Woodson include the following: Amanda Focke, Assistant Head of Special Collections and Archivisrs and Special Collections Librarians Rebecca Russell) Dara Flinn and Norie Guthrie. The Woodson's holdings range from the expected (documents and objects pertaining to che historyof Rice University and Houston) to che unexpected (collections on paranormal activity and the folk music era in Houston). Rice History A key resource for anyone interested in the history of Rice University is the Woodson Research Center in the special collections department of Fondren Library. One can find there the William Ward Watkin and Annie Ray Watkin University Archives containing historical records of the University's Board of Governors, administrative oA1ccs, presidents, university committees, academic departments, residential col!cges1 student organiucions and ocher university-related groups. The archives also include campus plans, drawings and blueprints, photographs, publications, video and audiotapes, ephemeral material and memorabilia. -

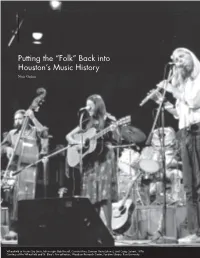

Putting the "Folk" Back Into Houston's Music History

Putting the “Folk” Back into Houston’s Music History Norie Guthrie 46 Wheatfield at Austin City Limits, left to right: Bob Russell, Connie Mims, Damian Hevia (drums), and Craig Calvert, 1976. Courtesy of the Wheatfield and St. Elmo’s Fire collection, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. While Austin enjoys international acclaim for its live music scene, Houston has long had one of the richest and most diverse musical histories of any city in Texas. Although not always adequately recognized for its contributions to the state’s songwriting traditions, Houston had a thriving folk music scene from the 1960s to the 1980s, helping launch the careers of numerous singer-songwriters. Founded in January 2016, the Houston Folk Music 47 Archive at the Woodson Research Center, which is part of Rice University’s Fondren Library, seeks to preserve and celebrate Houston’s folk music history, including its artists, venue owners, promoters, producers, and others. During the process of digitizing 2-track radio reels from Rice University’s student-run radio station, KTRU, I discovered a large number of folk music recordings, including live shows, interviews, and in-studio performances. Among these were such radio programs as Arbuckle Flat and Chicken Skin Music, which feature interviews and performances by Eric Taylor, Nanci Griffith, Lucinda Williams, Vince Bell, and others. The musicians tell stories about how they ended up in Houston and became part of the thriving folk community centered in the Montrose neighborhood. Not having grown up in the area, I was unaware that the local scene was so vibrant that several artists, including Lucinda Williams, had left Austin to join Houston’s tight-knit folk community. -

Fondren Fellows Project Opportunities 2019-2020

Fondren Fellows Project Opportunities 2019-2020 http://library.rice.edu/fondren-fellows 1) A Curated Resource for Open Science: Data Sharing, Publication, and Collaboration Mentor: Fred Oswald, Psychological Sciences Time Frame for Work: fall of 2019 Project Summary The Fondren Fellows program explicitly welcomes projects that “study potential approaches to open science at Rice.” To that end, the end product for the current project would be a curated online resource containing a series of links to websites, and associated descriptions, that are organized around the following four general topic areas central to today’s “open science movement”: data sharing, publication, and community-building. Data sharing reflects websites for sharing materials, measures, experimental protocols, datasets (and statistical, tabular, and visual summaries of data sets); publication reflects websites for preregistration (i.e., specifying the nature of one’s study prior to data collection), preprints, and post-publication review; collaboration can be as narrow as websites that encourage coordination within a research team, and as broad as websites that bring together international researchers across disciplines who are committed to open science. Key Tasks The Fondren Fellow would search, review, and report on websites under the previously mentioned topic areas, and then meet and discuss with me on a weekly basis, at a minimum. I already have started on this project myself and thus can offer a very good sense of how to pursue this project. Qualifications It would be helpful for students to have had at least some exposure to social sciences research where they had to analyze and interpret data (e.g., through a statistics or research methods class, through research engagement in a lab, or both). -

Freedmen's Town

Freedmen’s Town, Texas: A Lesson in the Failure of Historic Preservation By Tomiko Meeks he struggle to preserve the history Town before its demolition to make Tof Freedmen’s Town in Houston, way for I-45 in 1959. Texas, is entangled in the question- The original boundaries of able systems of urban renewal and Freedmen’s Town according to 1875 development, which inevitably work plat maps included twenty-eight to displace many of the poor African blocks inside of Fourth Ward on the American residents from the commu- southern banks of Buffalo Bayou, nity. For nearly forty years, African north of San Felipe Road, and west Americans have been systematically of the city’s center. Soon Freedmen’s forced from their neighborhood to Town became the center of opportu- make room for new construction nity and advancement for freed slaves. as more people move back into the The community played a critical role city. Freedmen’s Town, because of its in the Black experience in Houston, recognition as a “Historic District,” known throughout Houston’s African on the National Register of Historic American community as the “mother Places, should be immune to such ward.” By 1915, over four hundred actions. Unfortunately, this is not the Black owned businesses existed in case. Political figures, community Freedmen’s Town. The presence of groups, developers, the legal system, these institutions gave the commu- and preservation projects have all nity stability and tells the story of failed on varying levels to protect newfound opportunities for land and the historical value and integrity of homeownership among Blacks. -

Holman (Sanford) Papers, 1839-1845

Texas A&M University-San Antonio Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection Archives & Special Collections 2020 Holman (Sanford) Papers, 1839-1845 DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/findingaids A Guide to the Sanford Holman Papers, 1839-1845 Descriptive Summary Creator: Holman, Sanford, 1816-1843 Title: Sanford Holman Papers Dates: 1839-1845 Creator A veteran of the Texas Revolution who participated in the Battle of San Abstract: Jacinto, Sanford Holman (1816-1843) was a resident of San Augustine County, Texas, and served as a Customs Collector for the San Augustine District (1842-1843). Content The collection contains legal documents recording land transactions and Abstract: claims against the Sanford Holman estate. Identification: Doc 6176 Extent: 4 items (4 folders) Language: Materials are in English. Repository: DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Biographical Note William Sanford Holman was born in Fayette County, Kentucky, on 1816 April 12, a son of Isaac (1775-1835) and Anne Wigglesworth (1783-1841) Holman. A veteran of the War of 1812 and an attorney, Isaac Holman served as a Kentucky legislator and Tennessee state senator. Sanford Holman moved with his family to Lincoln County, Tennessee, around 1818. A shortage of money and a resulting credit crisis in that state in 1834 prompted the Holman family to move to San Augustine County, Texas, in three groups between 1834 October and 1835 March. The family soon became prominent in the area, with Sanford’s brother, William W. -

Development Plat Submittal Requirements

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department PROTECTED LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: Emancipation Park AGENDA ITEM: III OWNER: City of Houston HPO FILE NO: 07PL46 APPLICANT: City of Houston Parks and Recreation Department DATE ACCEPTED: 07/30/07 LOCATION: 3018 Dowling Street, Houston, Texas 77004 HAHC HEARING DATE: 08/22/07 30-DAY HEARING NOTICE: N/A PC HEARING DATE: 08/30/07 SITE INFORMATION: A ten-acre parcel described as Lot No. 25 in the James S. Holman Survey, within the limits of the City of Houston, Harris County, Texas, on the south side of Buffalo Bayou and bordered by Hutchins Street, Tuam Avenue, Dowling Street, and Elgin Avenue. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark and Protected Landmark Designation for Emancipation Park, including the Park Buildings. HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY: Emancipation Park, located in Houston’s Third Ward, is the oldest park site in the City of Houston. It was originally part of the land granted in 1839 to James S. Holman, who had served as Houston’s first mayor. The parcel was purchased in 1872 by a group of black community leaders for the celebration of Juneteenth (the anniversary of the emancipation of African-Americans in Texas on June 19, 1865), and it was donated to the City of Houston in 1916. For more than twenty years, Emancipation Park was the only public park in Houston open to African-Americans. In 1938-39, the Public Works Administration constructed on the park site a recreation center, swimming pool, and bathhouse, designed by prominent Houston architect William Ward Watkin.