Landmarks Preservation Commission May 15, 2007, Designation List 392 LP- 2253

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noble Mission (GB) -- Jesse's Justice A+ Based on the Cross of Galileo (IRE) and His Sons/Lear Fan Variant = 5.00

02/28/20 23:25:06 EST HYPOTHETICAL: Noble Mission (GB) -- Jesse's Justice A+ Based on the cross of Galileo (IRE) and his sons/Lear Fan Variant = 5.00 Nearctic, 54 br Northern Dancer, 61 b Natalma, 57 b Sadler's Wells, 81 b Bold Reason, 68 b Fairy Bridge, 75 b Special, 69 b $Galileo (IRE), 98 b Mr. Prospector, 70 b Miswaki, 78 ch Hopespringseternal, 71 ch Urban Sea, 89 ch =Lombard (GER), 67 ch Allegretta (GB), 78 ch =Anatevka (GER), 69 ch Noble Mission (GB), 09 b Northern Dancer, 61 b Danzig, 77 b Pas de Nom, 68 dk b/ Danehill, 86 b His Majesty, 68 b Razyana, 81 b Spring Adieu, 74 b =Kind (IRE), 01 b Blushing Groom (FR), 74 Rainbow Quest, 81 b ch =Rainbow Lake (GB), 90 b I Will Follow, 75 b Stage Door Johnny, 65 ch Rockfest, 79 ch Hypothetical Foal *Rock Garden II, 70 ch *Turn-to, 51 b Hail to Reason, 58 br Nothirdchance, 48 b Roberto, 69 b Nashua, 52 b Bramalea, 59 dk b/ Rarelea, 49 b Lear Fan, 81 b Nantallah, 53 b Lt. Stevens, 61 b *Rough Shod II, 44 b Wac, 69 b War Admiral, 34 br Belthazar, 60 br Blinking Owl, 38 br Jesse's Justice, 04 b Northern Dancer, 61 b Danzig, 77 b Pas de Nom, 68 dk b/ Chief's Crown, 82 b Secretariat, 70 ch Six Crowns, 76 ch Chris Evert, 71 ch My Reem, 93 ch =Wild Risk (FR), 40 b *Le Fabuleux, 61 ch =Anguar (FR), 50 b Fabulous Salt, 78 ch Round Table, 54 b Morgaise, 65 b Nanka, 55 b Pedigree Statistics Dosage Information Coefficient of Relatedness: 4.35% Pedigree Completeness: 100.00% Dosage Profile: 1 4 16 9 2 Inbreeding Coefficient: 3.01% Unique Ancestors: 935/2046 Dosage Index: 0.68 Center of Distribution: -

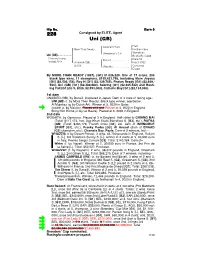

228 Consigned by Elite, Agent Uni (GB)

Hip No. Barn 9 228 Consigned by ELiTE, Agent Uni (GB) Southern Halo . Halo More Than Ready . {Northern Sea {Woodman’s Girl . Woodman Uni (GB) . {Becky Be Good Chestnut mare; Dansili . Danehill foaled 2014 {Unaided (GB) . {Hasili (IRE) (2009) {Wosaita . Generous {Eljazzi By MORE THAN READY (1997), [G1] $1,026,229. Sire of 17 crops, 203 black type wnrs, 11 champions, $195,421,756, including More Joyous [G1] ($4,506,154), Roy H [G1] ($3,139,765), Phelan Ready [G1] ($2,809,- 560), Uni (GB) [G1] ($2,380,880), Sebring [G1] ($2,365,522) and Rush- ing Fall [G1] (to 5, 2020, $2,553,000), Catholic Boy [G1] ($2,134,000). 1st dam UNAIDED (GB), by Dansili. Unplaced in Japan. Dam of 4 foals of racing age-- UNI (GB) (f. by More Than Ready). Black type winner, see below. Al Mujahaz (g. by Dutch Art). Winner at 5, 2020 in Qatar. Isolate (c. by Maxios). Placed at 3 and Winner at 4, 2020 in England. Bring Him Home (c. by Le Havre). Placed at 3, 2020 in England. 2nd dam WOSAITA, by Generous. Placed at 3 in England. Half-sister to CHIANG MAI (Total: $117,173, hwt, Aga Khan Studs Blandford S. [G3], etc.), RAFHA (GB) (Total: $383,179, French Oaks [G1], etc. dam of INVINCIBLE SPIRIT [G1], etc.), Franky Furbo [G3]; Al Anood (dam of ENAAD [G2] champion; etc.), Chamela Bay, Fayfa. Dam of 9 winners, incl.-- WHAZZIS (f. by Desert Prince). 2 wins, 44,700 pounds in England, Valiant S. [L], 3rd Vodafone Surrey S. [L]; winner in 2 starts at 3, 40,500 euro in Italy, Premio Sergio Cumani [G3]. -

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers Press Event Newmarket, Thursday, June 13, 2019 BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR ROYAL ASCOT 2019 Deirdre (JPN) 5 b m Harbinger (GB) - Reizend (JPN) (Special Week (JPN)) Born: April 4, 2014 Breeder: Northern Farm Owner: Toji Morita Trainer: Mitsuru Hashida Jockey: Yutaka Take Form: 3/64110/63112-646 *Aimed at the £750,000 G1 Prince Of Wales’s Stakes over 10 furlongs on June 19 – her trainer’s first runner in Britain. *The mare’s career highlight came when landing the G1 Shuka Sho over 10 furlongs at Kyoto in October, 2017. *She has also won two G3s and a G2 in Japan. *Has competed outside of Japan on four occasions, with the pick of those efforts coming when third to Benbatl in the 2018 G1 Dubai Turf (1m 1f) at Meydan, UAE, and a fast-finishing second when beaten a length by Glorious Forever in the G1 Longines Hong Kong Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin, Hong Kong, in December. *Fourth behind compatriot Almond Eye in this year’s G1 Dubai Turf in March. *Finished a staying-on sixth of 13 on her latest start in the G1 FWD QEII Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin on April 28 when coming from the rear and meeting trouble in running. Yutaka Take rode her for the first time. Race record: Starts: 23; Wins: 7; 2nd: 3; 3rd: 4; Win & Place Prize Money: £2,875,083 Toji Morita Born: December 23, 1932. Ownership history: The business owner has been registered as racehorse owner over 40 years since 1978 by the JRA (Japan Racing Association). -

(IRE) Barn 1&6 Hip No

Consigned by Lane's End, Agent Hip No. Barn 184 DISTINCTIVE LOOK (IRE) 1 & 6 Bay Mare; foaled 2003 Northern Dancer Danzig............................... Pas de Nom Danehill ............................ His Majesty Razyana............................. Spring Adieu DISTINCTIVE LOOK (IRE) Roberto Silver Hawk....................... Gris Vitesse Magnificient Style............. (1993) Icecapade Mia Karina ........................ Basin By DANEHILL (1986). Hwt. in Europe, black-type winner of $321,064, Lad- broke Sprint S. [G1], etc. Leading sire 17 times in Australia, England, France, Hong Kong and Ireland, sire of 14 crops of racing age, 2499 foals, 2086 starters, 347 black-type winners, 27 champions, 1608 winners of 5373 races and earning $211,135,746. Leading broodmare sire in Czech Republic, England, France, and U.S., sire of dams of 194 black- type winners, 12 champions, including Danedream, Shocking, Sepoy. 1st dam MAGNIFICIENT STYLE, by Silver Hawk. 2 wins in 4 starts at 3, £30,744, in Eng- land, Tattersalls Musidora S. [G3], etc.; placed, $27,290, in N.A./U.S. (To- tal: $73,883). Half-sister to SIBERIAN SUMMER [G1] ($501,615). Dam of 12 registered foals, 10 of racing age, 10 to race, 10 winners, including-- NATHANIEL (c. by Galileo). 4 wins at 3 and 4, 2012, £1,206,475, in Eng- land, hwt. colt at 3 on English Hand., 9 1/2 - 11 and 11 - 14 fur., Betfair King George VI & Queen Elizabeth S. [G1], Coral Eclipse S. [G1], King Edward VII S. [G2], etc. (Total: $1,929,411). PLAYFUL ACT (IRE) (f. by Sadler's Wells). 4 wins in 6 starts to 3, £217,455, in England, hwt. -

SUMMER MAGAZINE 2019 INTRODUCTION P ARK HOUSE STABLES Orse Racing Has Always Been Unpredictable and in Many Ways That Is Part of Its Attraction

P ARK HOUSE STABLES SUMMER MAGAZINE 2019 INTRODUCTION P ARK HOUSE STABLES orse racing has always been unpredictable and in many ways that is part of its attraction. It can provide fantastic high H points but then have the opposite effect on one’s emotions a moment later. Saturday 13 July was one of those days. Having enjoyed the thrill of watching Pivoine win one of the season’s most important handicaps, closely followed by Beat The Bank battling back to win a second Summer Mile, the ecstasy of victory was replaced in a split second by a feeling of total horror with Beat The Bank suffering what could immediately be seen to be an awful injury. Whilst winning races is important to everyone at Kingsclere, the vast majority of people who work in racing do it because they love horses and there is nothing more cruel in this sport than losing a horse, whether it be on the gallops or on the racecourse. Beat The Above: Ernie (Meg Armes) is judged Best Puppy at the Kingsclere Dog Show Bank was a wonderful racehorse and a great character and will be remembered with huge affection by everyone at Park House. Front cover: BEAT THE BANK with Sandeep after nishing second at Royal Ascot Whilst losing equine friends is never easy it is not as difficult as Back cover: LE DON DE VIE streaks clear on Derby Day at saying goodbye to two wonderful friends in Lynne Burns and Dr Epsom Elizabeth Harris. Lynne was a long time member of the Kingsclere Racing Club and her genial personality and sense of fun endeared CONTENTS her to everyone lucky enough to meet her. -

346 Aga Khan Studs 346 SHAZIA(FR)

346 Aga Khan Studs 346 Sadler's Wells Galileo Urban Sea NEW APPROACH Ahonoora Park Express SHAZIA (FR) Matcher Niniski Lomitas chesnut filly 2014 SHALANAYA La Colorada 2006 (IRE) Shalamantika Nashwan 1999 Sharamana Race record: 1 win (17), placed 3 times at 2 and 3 years. 1st dam SHALANAYA, 3 wins, placed 5 times at 3 and 4 years in FR, JPN & CAN, Prix de l'Opéra (Gr.1), de Liancourt at Longchamp (L.), 2nd Prix Ganay (Gr.1), 3rd E. P. Taylor S.(Gr.1), 447 262 €. Dam of 6 foals, 4 of racing age, 2 winners incl.: Shalakar, (c., Cape Cross), 2 wins, placed once at 3 years. Shalla, (f.2015, Redoute's Choice), in training with Mikel Delzangles. N., (c.2016, Nathaniel), in training with Mikel Delzangles N., (f.2017, Zoffany). She is in foal to Exceed And Excel. 2nd dam Shalamantika, 1 win, placed 6 times from 8 starts at 3 years in GB, 3rd Harvest St.(L.). Dam of 8 foals of racing age, 3 winners incl.: SHALANAYA, (see above). SHANKARDEH, (f., Azamour), 3 wins, pl. 3 times from 6 starts at 3, Prix Chaudenay (Gr.2), 2nd Lillie Langtry St.(Gr.3), 3rd Prix Royal-Oak (Gr.1), de Malleret (Gr.2), 152 413 €. Dam of: Shakdara, (f.2015, Street Cry), in training with Alain de Royer Dupré. N., (c.2016, Elusive Quality), in training with Alain de Royer Dupré. N., (f.2017, Mizzen Mast). She is in foal to Dawn Approach. Shanndiyra, (f., King’s Best). Dam of: Shahnaza (f.2015, Azamour), placed in 1 outing this year, in training with Alain de Royer Dupré. -

Oasis Dream Filly Tops Challenging Orby Sale Cont

FRIDAY, 2 OCTOBER 2020 NO LOVE IN RAIN-HIT ARC OASIS DREAM FILLY TOPS With France blighted by persistent rain and more in the CHALLENGING ORBY SALE forecast, there will be no Love (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) in Sunday=s i3,000,000 G1 Qatar Prix de l=Arc de Triomphe as the withdrawal of the G1 1000 Guineas, G1 Epsom Oaks and G1 Yorkshire Oaks heroine left 14 to attempt to mount a challenge to Enable (GB) (Nathaniel {Ire}). As well as being graced with that news, Juddmonte=s superstar mare also drew a favourable berth in five as she looms ever closer to her historic bid for a third renewal of the ParisLongchamp feature. Her stablemate Stradivarius (Ire) (Sea the Stars {Ire}) fared far worse from the draw and Bjorn Nielsen=s champion stayer will exit from stall 14 with only the supplemented Serpentine (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) positioned wider. Ballydoyle=s streamlined force also includes the likely pace-setter Sovereign (Ire) in 10, Japan (GB) in 11 and Mogul (GB) in three, with Ryan Moore now switching to the latter of the remaining Galileos. Jean-Claude Rouget=s duo Sottsass (Fr) (Siyouni {Fr}) and Raabihah (Sea the Stars {Ire}) will break from four and two respectively. Cont. p7 Lot 343, the sale-topping Oasis Dream filly | Goffs By Emma Berry DONCASTER, UKCThe weather brightened for the final session of the Goffs Orby Sale but it has to be said that the vibe did not. True, the clearance rate remained at a respectable level, with those vendors who decided to sell continuing to be realistic in their reserves. -

Nathaniel J. and Ann C. Wyeth House, 190 Meisner Avenue, Staten Island

Landmarks Preservation Commission May 15, 2007, Designation List 392 LP- 2253 Nathaniel J. and Ann C. Wyeth House, 190 Meisner Avenue, Staten Island. Built 1856 Landmark Site: Borough of Staten Island Tax Map Block 2268, Lot 180 On April 10, 2007 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Nathaniel J. and Ann C. Wyeth House, 190 Meisner Avenue, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 9). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Six speakers including a representative of the owner of the building and representatives for the Preservation League of Staten Island, Historic Districts Council, the Metropolitan Chapter of the Victorian Society in America, and the West Brighton Restoration Society testified in favor of the designation. There were no speakers in opposition to the designation. The Commission has received letters in support of the designation from Council member James S. Oddo, the Municipal Art Society, and the Rego-Forest Preservation Council. (A public hearing had previously been held on this item on September 13, 1966, [LP-0365].) Summary The Nathaniel J. and Ann C. Wyeth house is significant for its architectural design and for its historical and cultural associations with two important occupants. Picturesquely sited on Lighthouse (Richmond) Hill, this impressive Italianate villa, constructed around 1856 for Nathaniel J. and Ann C. Wyeth, is a fine example of the mid-nineteenth villas which once dotted the hillsides of Staten Island and are now becoming increasingly rare. Named for his uncle, the noted explorer of the Pacific Northwest, Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth (1831-1916) was a prominent corporate attorney, state legislator, and civic leader who maintained a law office in this house. -

65 Aga Khan Studs 65 SHAHINDA(FR)

65 Aga Khan Studs 65 Green Desert Cape Cross Park Appeal SEA THE STARS Miswaki Urban Sea SHAHINDA (FR) Allegretta Danehill Danehill Dancer bay filly 2014 SHAMANOVA Mira Adonde 2007 (IRE) Shamadara Kahyasi 1993 Shamarzana Race record: 1 win (17), placed once at 3 years. 1st dam SHAMANOVA, 3 wins, placed 9 times at 3 and 4 years, Prix La Moskowa at Chantilly (L.), 2nd Prix de Malleret (Gr.2), Minerve (Gr.3), de Lutèce (Gr.3), Allez France (Gr.3), 3rd Prix de Pomone (Gr.2), Maurice de Nieuil (Gr.2), Gladiateur (Gr.3), 4th Prix de Royallieu (Gr.2), 186 700 €. Dam of 4 foals, 3 of racing age incl.: Shabana, (f.2015, Pivotal), in training with Alain de Royer Dupré. N., (f.2016, Oasis Dream), in training with Alain de Royer Dupré. 2nd dam SHAMADARA, 2 wins, placed 3 times from 6 starts at 3 years, Prix de Malleret (Gr.2), 2nd Irish Oaks (Gr.1), 117 472 €. Dam of 12 foals, 9 winners incl.: SHAMDALA, (f. Grand Lodge) 6 wins, $919,374, GP di Milano (Gr.1), Px Vicomtesse Vigier (Gr.2), Chaudenay (Gr.2), de Lutèce (Gr.3), 2nd Px du Cadran (Gr.1), 3rd HK Vase (Gr.1). Dam of a winner. SHAMAKIYA, (f., Intikhab), 2 wins, placed twice from 4 starts at 3, Prix de Thiberville at Longchamp (L.), 2nd Prix de Royaumont (Gr.3), 3rd Prix de Malleret (Gr.2), 66 875 €. Dam of: SHAMKALA, (f.), 3 wins at 2 and 3, Prix Cléopâtre (Gr.3). Dam of: N., (c.2016, Sea The Stars), in training with Alain de Royer Dupré. -

Newsletter Winter 2019

Newsletter Winter 2019 “Telescope” by Grace. THE SHADE OAK NEWSLETTER: 2020 SEASON This is the sort of winter day I love: crisp, dry, the sun rising low in the sky and the fields and hedges glistening with dew as they invite the thrilling chase that surely awaits me and my trusty charge, Sir Francis. So, why, you might very well ask (as I did myself not five minutes ago), am I locked in the loo with just an ipad for company? “That’s where most people read it so that’s where you can write it,” my lovely wifie kindly explained. So here I am, poised to bring you informative information and insightful insights into stud life, stallions, breeding and anything else that comes into my head so that I can produce sufficient words to earn early release, aided only by my trusty assistant who sits poised at the other end of an email connection ready to dig up some relevant statistic I can’t quite call to mind or remind me of the odd fact that I asked him to make a note of for just this moment. So here, just so long as the broadband doesn’t go down, is the annual Shade Oak Newsletter… THE SEARCH FOR A STALLION For the second year running we have no news of a new both Telescope and Dartmouth and a great trainer of stallion arriving at Shade Oak for the forthcoming season. I middle-distance horses, made the dreadful mistake of realise that breeders are often excited at the thought of using running him in a 10 furlong Group 1 rather than tackling a new stallion. -

Passages from the French and Italian Note-Books of Nathaniel

- - -- - - - - | - - - | |-- - - | -- - -. | - - - | |-- ||-- - - -- - - | - - -- . -- - - | | |-- THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LIBRARY ‘; HASSAGES ; : . ‘...."-- ; : : *R& fire ####&#AN pilºtAiiANº NOTE-BOOKS of NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE. * VOL. II. B O ST ON : JAMES R. OSGoo D AND com PANY., LATE Ticknor & Fields, AND FIELDs, Osgood, & Co. 1872. r r * - r * * * * * * * * r r tº - r r , , . - * * * * * * r r e. * * * * - - r t t e < ‘. r * , , t * * - - - - * r * * e * - •.' * . - r * * > . * , t r * * * ~ * - r f e • * , . r e ºr ‘. r r - - * r - r * * - r r r r ºr r * * * * * e e r * * * * * " * * * * * * * * * * - - - ... r * - * . “. * * - * e º 'º e e -e e - *ee - - Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1871, BY JAMES R. OSGOOD & Co., in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. UNIVERSITY PREss: Welch, BIGELow, & Co., CAMBRIDGE. PºA SSAGES HAWTHORNE'S NOTE-BOOKS IN FRANCE AND ITALY. -6 FLORENCE – continued. June 8th. —I went this morning to the Uffizzi gallery. The entrance is from the great court of the palace, which communicates with Lung' Arno at one end, and with the Grand Ducal Piazza at the other. The gallery is in the upper story of the palace, and in the vestibule are some busts of the princes and cardinals of the Medici family, - none of them beau- ~ tiful, one or two so ugly as to be ludicrous, especially one who is all but buried in his own wig. I at first travelled slowly through the whole extent of this long, long gallery, which occupies the entire length of the palace on both sides of the court, and is full of sculpture and pictures. The latter, being opposite to the light, are not seen to the best advantage ; but it is the most perfect collection, in a chronological series, that I have seen, comprehending specimens of all the masters since painting began to be an art. -

Horse Versus Man Looms in Classic

MONDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2017 HORSE VERSUS MAN SIGNIFICANT FORM--AND TALENT--ON DISPLAY IN MISS GRILLO LOOMS IN CLASSIC Significant Form (Creative Cause) crossed the wire first in her Aug. 27 unveiling at Saratoga, only to be disqualified for drifting inward and causing interference into the first turn. She put that all behind her Sunday, producing the same result--minus the antics--and capturing the GIII Miss Grillo S. at Belmont. The gray, a $575,000 OBS April 2-year-old purchase for Stephanie Seymour Brant, tracked the pace and pounced in the stretch, holding off the highly regarded pair of Best Performance (Broken Vow) and Orbolution (Orb) to prevail. After the race, trainer Chad Brown confirmed that the winner likely punched her ticket for the starting gate for the GI Breeders= Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf Nov. 3. AI was really impressed with how she fought back late in the stretch when [Best Performance] challenged her,@ said Brown. AThis win is really encouraging going forward and heading into the Breeders' Cup.@ Cont. p3 Gun Runner may be the only horse standing in the way of a Bob IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Baffert trainee winning the Breeders= Cup Classic | Sarah K. Andrew ARC ANGEL The Week in Review, by Bill Finley Juddmonte’s Enable (GB) (Nathaniel {Ire}), with Frankie Dettori Gun Runner (Candy Ride {Arg}) has earned the right to be in the irons, earned her fifth victory at the highest level in the called the best horse in the U.S. and he will come into the GI G1 Qatar Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe at Chantilly on Sunday for trainer John Gosden.