Download Free Sampler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Silence Is Your Praise” Maimonides' Approach To

Rabbi Rafael Salber “Silence is your praise” Maimonides’ Approach to Knowing God: An Introduction to Negative Theology Rabbi Rafael Salber The prophet Isaiah tells us, For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are my ways your ways, saith the Lord. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways. 73 The content of this verse suggests the inability of mankind to comprehend the knowledge and thoughts of God, as well as the 73 Isaiah 55: 8- 9. The context of the verse is that Isaiah is conveying the message to the people of Israel that the ability to return to God (Teshuvah) is available to them, since the “traits” of God are conducive to this. See Moreh Nevuchim ( The Guide to the Perplexed ) 3:20 and the Sefer haIkkarim Maamar 2, Ch. 3. 65 “Silence is your praise”: Maimonides’ Approach to Knowing God: An Introduction to Negative Theology divergence of “the ways” of God and the ways of man. The extent of this dissimilarity is clarified in the second statement, i.e. that it is not merely a distance in relation, but rather it is as if they are of a different category altogether, like the difference that exists between heaven and earth 74 . What then is the relationship between mankind and God? What does the prophet mean when he describes God as having thoughts and ways; how is it even possible to describe God as having thoughts and ways? These perplexing implications are further compounded when one is introduced to the Magnum Opus of Maimonides 75 , the Mishneh Torah . -

Hirsch on Chanukah*

RABBI SAMSON RAFAEL HIRSCH ON CHANUKAH* Excerpted by Rabbi Moshe ben Asher, Ph.D. Originally vfubj [Chanukah] belonged to a se- the pleasure derived from the awareness of a nobler ries of festive days listed in Megillath Taanith. existence. These days conveyed recollections of blissful Hellenistic culture is a protector of rights and events that proclaimed the invisible yet open inter- freedom. These concepts, however, are applied vention of God’s almighty rule for the preservation only to those who are educated; they are subject to of the people and the Law. an arrogance that claims that the rights of human The silent beam of friendly lights relates the beings begin only after they have attained a certain victory of light over darkness and tells of the level of culture. Therefore, sensitivity and concern “pure” Menorah’s rescue from the clutches of regarding one’s own self, and those close to one- Greek corruption. Chanukah recounts the rededica- self, are paired with an enormous callousness, with tion of the Sanctuary, which had been despoiled by an utmost cruelty, which assumes that the inferior the Greeks. The celebration of the eight-day Feast “uneducated masses” lack genuine feelings of of Light recalls the victorious survival of the Sanc- honor or a sensitivity for freedom or human rights. tuary, not the courage of the Maccabees. It does not Attica, so vainglorious about its rights and liberties, commemorate the liberation of the Jewish home- saw no contradiction in the fact that three-quarters land from the grip of enemy hands; it hails the of its inhabitants lived in servitude and slavery. -

Orthodoxy in American Jewish Life1

ORTHODOXY IN AMERICAN JEWISH LIFE1 by CHARLES S. LIEBMAN INTRODUCTION • DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF ORTHODOXY • EARLY ORTHODOX COMMUNITY • UNCOMMITTED ORTHODOX • COM- MITTED ORTHODOX • MODERN ORTHODOX • SECTARIANS • LEAD- ERSHIP • DIRECTIONS AND TENDENCIES • APPENDLX: YESHIVOT PROVIDING INTENSIVE TALMUDIC STUDY A HIS ESSAY is an effort to describe the communal aspects and institutional forms of Orthodox Judaism in the United States. For the most part, it ignores the doctrines, faith, and practices of Orthodox Jews, and barely touches upon synagogue hie, which is the most meaningful expression of American Orthodoxy. It is hoped that the reader will find here some appreciation of the vitality of American Orthodoxy. Earlier predictions of the demise of 11 am indebted to many people who assisted me in making this essay possible. More than 40, active in a variety of Orthodox organizations, gave freely of their time for extended discussions and interviews and many lay leaders and rabbis throughout the United States responded to a mail questionnaire. A number of people read a draft of this paper. I would be remiss if I did not mention a few by name, at the same time exonerating them of any responsibility for errors of fact or for my own judgments and interpretations. The section on modern Orthodoxy was read by Rabbi Emanuel Rackman. The sections beginning with the sectarian Orthodox to the conclusion of the paper were read by Rabbi Nathan Bulman. Criticism and comments on the entire paper were forthcoming from Rabbi Aaron Lichtenstein, Dr. Marshall Ski are, and Victor Geller, without whose assistance the section on the number of Orthodox Jews could not have been written. -

B”H Introduction in Our First Article on the AOJS, We Explored Interactions

B”H Introduction In our first article on the AOJS, we explored interactions between Rebbe and Dr. Offenbacher — its founder. In this article, we will make note of additional interactions the Rebbe had with the AOJS. While the full story of the relationship between the Rebbe and AOJS is worthy of a more detailed study, we will focus here on a few specific interactions. Dr. Cyril Domb Professor Dr. Cyril (Yechiel) Domb (5681-5772) was born in North London, England, into a Chasidic Jewish family. He was deeply affected and inspired by his grandparents who were deeply religious Jews. He, in turn, retained this deep religious feeling, was meticulous in his observance of the Mitzvos — which always took precedence over activities for professional advancement1— and spent much of his free time devoted to Talmudic studies (including attending a daily Daf Yomi Shiur). Dr. Domb led a long and fruitful career in the study of Theoretical physics and statistical mechanics, lecturing at Oxford and Cambridge Universities, King’s College, London University, Bar-Ilan University, University of Maryland, Yeshiva University, Hebrew University, Jerusalem College of Technology and the Weizmann Institute. Shortly before making aliyah to Israel, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. After encountering AOJS members in 5718, during a sabbatical year at the University of Maryland2, he helped found and lead a sister organization of the AOJS in London, in 57223. In 1971, Domb became the general editor of a book series which was sponsored by the AOJS, the purpose of which was to systematically present material which could be used for Jewish education. -

The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik Z"L

The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik z"l Byline: Rabbi Dr. Nathan Lopes Cardozo is Dean of the David Cardozo Academy in Jerusalem. Thoughts to Ponder 529 The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik z”l * Nathan Lopes Cardozo Based on an introduction to a discussion between Professor William Kolbrener and Professor Elliott Malamet (1) Honoring the publication of Professor William Kolbrener’s new book “The Last Rabbi” (2) Yad Harav Nissim, Jerusalem, on Feb. 1, 2017 Dear Friends, I never had the privilege of meeting Rav Soloveitchik z”l or learning under him. But I believe I have read all of his books on Jewish philosophy and Halacha, and even some of his Talmudic novellae and halachic decisions. I have also spoken with many of his students. Here are my impressions. No doubt Rav Soloveitchik was a Gadol Ha-dor (a great sage of his generation). He was a supreme Talmudist and certainly one of the greatest religious thinkers of our time. His literary output is incredible. Still, I believe that he was not a mechadesh – a man whose novel ideas really moved the Jewish tradition forward, especially regarding Halacha. He did not solve major halachic problems. This may sound strange, because almost no one has written as many novel ideas about Halacha as Rav Soloveitchik (3). His masterpiece, Halakhic Man, is perhaps the prime example. Before Rav Soloveitchik appeared on the scene, nobody – surely not in mainstream Orthodoxy – had seriously dealt with the ideology and philosophy of Halacha (4). Page 1 In fact, the reverse is true. -

H E a R T B E

HEARTBEAT heartbeatAmerican Committee for Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem 49 West 45th Street • New York, NY 10036 212-354-8801 • www.acsz.org I SRAEL IS COUNTING ON US...TO CARE AND TO CURE SPRING 2011 KESTENBAUM FAMILY MAKES LEADERSHIP GIFT TO DEDICATE ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY MACHINE IN THE PEDIATRIC CARDIOLOGY DEPARTMENT Alan and Deborah Kestenbaum have been involved with Shaare HEARTBEAT Zedek for more than two decades. Deborah’s father, Hal Beretz, served as the chair of the Hospital’s International Board of Highlights Governors, her mother Anita is a member of the National Women’s Division and Deborah currently serves as the Chair of the Development Board of the Women’s Division. PAGE 8 In recent years, Deborah, who has always metals with Glencore and Philipp Brothers in Profiles in Giving been involved in countless charitable endeavors, New York. Dr. Jack and Mildred Mishkin her local synagogue and her children’s schools, Recently, the Kestenbaums decided to Dr. Monique and Mordecai Katz has taken on a more prominent leadership take their leadership to the next level by mak- role in the Shaare Zedek Women’s Division. ing a magnanimous gift to purchase a new PAGE 4-7 A graduate of Queens College with a BA in Echocardiography machine for the Pediatric Economics, Deborah explains, “Shaare Zedek Cardiology Department. Highlights from the Hospital has always been a part of my family and I am looking forward to increasing my involvement While advanced cardiac care is not typ- Hospital Opens New Cosmetic with this incredible Hospital.” ically associated with younger patients, the Care Center and New Digestive reality is that a large number of children do Diseases Institute Alan, holds a BA in Economics from indeed face serious cardiac problems. -

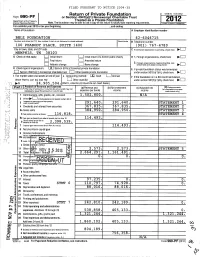

Return of Private Foundation Form 990-PF

' FILED PURSUANT TO NOTICE 2004-35 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust ^O Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2012 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number BELZ FOUNDATION 62-6046715 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number 100 PEABODY PLACE, SUITE 1400 (901) 767-4780 City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here ► MEMPHIS, TN 38103 G Check all that apply: L_J Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Add ress chan ge Name c hange check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization . LXJ Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated = Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust = Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here Fair market value X I of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Cash L_J Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part 11, col (c), line 16) = Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ► s 2 4 , 9 0 5 , 5 0 4 . -

Canadian Friends of Boys Town Jerusalem

Shana Tova Happy New Year Canadian Friends of Boys Town Jerusalem Boys Town Jerusalem is a unique ‘community of youth’ where boys from every economic, social and cultural Mylwvry rivn tyrq background acquire an inspiring technical, Torah and academic education which is so vital to Israel. September 2012 | Volume 11 | No. 2 Boys Town Jerusalem Impresses the Pros First and Only High School in Israel on Oracle System As the 2011-2012 school year give them enough. The results: their began last September, Boys Town average grade on the bagrut (national Jerusalem students were once again matriculation) exam was 85%, and making history. The results and six students scored 100%!”, Saruk the rewards have been remarkable. reported. Boys Town Jerusalem was the first AND ONLY high school Open Source systems are based on in Israel to offer a curriculum in the groundbreaking “Solaris” system “Open Source Computer Operating created by Sun Microsystems, now a Systems” (the Oracle Corporation’s part of Oracle Corporation. In 2011, “OpenSolaris”). Last week, five Boys Town Jerusalem was selected of our seventeen pioneer students by Israel’s Ministry of Education to were invited to present their senior pioneer the Solaris curriculum. This projects to the Israel-based Oracle follows a Boys Town milestone in Users Group Forum, a gathering of 2000 when we were the first high the top echelon of Israel’s computer school designated as the center of professionals. instruction for the CISCO Networking Management Program. Today, Boys Town is the country’s only high school licensed to prepare students in The students’ presentation left much of the audience visibly stunned. -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

The Rabbi Naftali Riff Yeshiva

AHHlVERSARtJ TOGtTHtR! All new orden will receive a Z0°/o Discount! Minimum Order of $10,000 required. 35% deposit required. (Ofter ends February 28, 2003) >;! - . ~S~i .. I I" o i )• ' Shevat 5763 •January 2003 U.S.A.$3.50/Foreign $4.50 ·VOL XXXVI/NO. I THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN) 0021-6615 is published monthly except July and August by the Agudath Israel of America, 42 Broadway, New York, NY10004. Periodicals postage paid in New York, NY. Subscription $24.00 per year; two years, $44.00; three years, $60.00. Outside ol the United States (US funds drawn on a US bank only) $12.00 surcharge per year. Single copy $3.50; foreign $4.50. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to; The Jewish Observer, 42 a.roadway, NY. NY.10004. Tel:212-797-9000, Fax: 646-254-1600. Printed in the U.S.A. KIRUV TODAY IN THE USA RABBI NISSON WOLPIN, EDITOR EDITORIAL BOARD 4 Kiruv Today: Now or Never, Rabbi Yitzchok Lowenbraun RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS Chairman RABBI ABBA BRUONY 10 The Mashgiach Comes To Dallas, Kenneth Chaim Broodo JOSEPH FRIEOENSON RABBI YISROEL MEIR KIRZNER RABBI NOSSON SCHERMAN 16 How Many Orthodox Jews Can There Be? PROF. AARON TWEASKI Chanan (Anthony) Gordon and Richard M. Horowitz OR. ERNST L BODENHEIMER Z"l RABBI MOSHE SHERER Z"L Founders 30 The Lonely Man of Kiruv, by Chaim Wolfson MANAGEMENT BOARD AVI FISHOF, NAFTOLI HIRSCH ISAAC KIRZNER, RABBI SHLOMO LESIN NACHUM STEIN ERETZ YISROEL: SHARING THE PAIN RABBI YOSEF C. GOLDING Managing Editor Published by 18 Breaking Down the Walls, Mrs. -

The Jewish Center SHABBAT BULLETIN MAY 5, 2018 • PARSHAT EMOR • 20 IYAR 5778

The Jewish Center SHABBAT BULLETIN MAY 5, 2018 • PARSHAT EMOR • 20 IYAR 5778 SHABBAT SCHEDULE The Jewish Center EREV SHABBAT Centennial Dinner 7:00PM Minchah Tuesday, June 5th, 2018 at The Plaza 7:00PM Young Leadership (5th floor) Honoring: 7:36PM Candle lighting Rabbi Dr. Leo Jung z”l Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm SHABBAT Rabbi Isaac Bernstein z”l 7:45AM Hashkama Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter 8:30AM Israel Silverstein Rambam shiur with Rabbi Yosie Rabbi Dr. Ari Berman Levine Rabbi Yosie Levine 9:00AM Shacharit 9:15AM Hashkama Shiur with Rabbi Noach Goldstein, Is Scholar In Residence Weekend with Sally Mayer Yom Kippur a Festival or a Shabbat Shabbat, May 4-5th 9:23AM Sof Zman Kriat Shema The Jewish Center is excited to welcome back our former Education Director 9:30AM Young Leadership Sally Mayer to deliver the Annual Martha Sonnenschein Memorial Lecture. Shabbat Morning Public Lecture 11AM 9:30AM Teen Minyan Israel at 70: Personal Reflections on Life After Aliyah 10:00AM Youth Groups Shabbat Afternoon Tanach Shiur 6:15PM 11:00AM Public Lecture with Sally Mayer, Israel at 70: Megillat Ruth: “Hyperlinks” in Tanach Personal Reflections on Life After Aliyah Seudah Shlishit 7:45PM 4:00PM Bikkur Cholim/Bikkur in the Home Counting up to my Matan Torah: Sefirat HaOmer and Making (meet at 730 Columbus Ave.) Torah Personal 6:15PM Tanach Series with Sally Mayer, Megillat Ruth: “Hyperlinks” in Tanach The Jewish Center Centennial 6:30PM Daf Yomi Hachnasat Sefer Torah th 6:30PM Parent-Child learning with Ora Weinbach Sunday, May 6 7:15PM Minchah Join us for The JC Centennial Seudah Shlishit with Sally Mayer, Counting up to my Matan community-wide Sefer Torah Torah: Sefirat HaOmer and Making Torah Personal Dedication. -

Why I Left My Old Home and What I Have Accomplished in America

Chapter 4 Why I Left My Old Home and What I Have Accomplished in America Aaron Domnitz (Aba Beitani) b. 1884,Romanovo, Belarus To U.S.: 1906;settled in Baltimore, Md. The autobiography of Aaron Domnitz is the purest example of the maskil type in this collection. A deeply pious and zealous student of Gemara as a child and youth, he was drawn to the study of Hebrew literature and secular subjects as a yeshiva student. Influenced by the revolutionary fervor sur- rounding him, Domnitz romanticized workers and industrial labor but lasted only a brief time in the “shop” when he arrived in the United States. Domnitz describes his experiences as a member of the literary and intellectual circle known as “Di Yunge,” the Young Ones, while living in the Bronx in the first decades of the twentieth century. An ideal informant, the writer has a knack for keen observation, evoking his surroundings with a sharp eye and close detail, always placing the phenomena he describes vividly in their historical contexts. Introduction I want to make use of the autobiographical form, so I will skip many, many things that have occurred in my life. I will record only those details of my childhood that have in my consciousness some connection with my later urge to travel somewhere. Ruminating over my past has renewed in my memory several details that at one time made a strong impression on me, and I portray them here. These too would be interesting for a histo- rian who might sometime ruminate over old documents and want to form 124 Why I Left My Old Home and What I Have Accomplished in America 125 a complete picture of the people who took part in the great Jewish immi- gration at the beginning of the century.