Phd Thesis Department of English Studies Durham University 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Quest Motif in Snyder's the Back Country

LUCI MARÍA COLLIN LA VALLÉ* ? . • THE QUEST MOTIF IN SNYDER'S THE BACK COUNTRY Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Pós- Graduação em Letras, Área de Concentração em Literaturas de Língua Inglesa, do Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes da Universidade Federal ' do Paraná, para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Letras. Orientador: Profa. Dra. Sigrid Rénaux CURITIBA 1994 f. ] there are some things we have lost, and we should try perhaps to regain them, because I am not sure that in the kind of world in which we are living and with the kind of scientific thinking we are bound to follow, we can regain these things exactly as if they had never been lost; but we can try to become aware of their existence and their importance. C. Lévi-Strauss ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to acknowledge my American friends Eleanor and Karl Wettlaufer who encouraged my research sending me several books not available here. I am extremely grateful to my sister Mareia, who patiently arranged all the print-outs from the first version to the completion of this work. Thanks are also due to CAPES, for the scholarship which facilitated the development of my studies. Finally, acknowledgment is also given to Dr. Sigrid Rénaux, for her generous commentaries and hëlpful suggestions supervising my research. iii CONTENTS ABSTRACT vi RESUMO vi i OUTLINE OF SNYDER'S LIFE viii 1 INTRODUCTION 01 1.1 Critical Review 04 1.2 Cultural Influences on Snyder's Poetry 12 1.2.1 The Counter cultural Ethos 13 1.2.2 American Writers 20 1.2.3 The Amerindian Tradi tion 33 1.2.4 Oriental Cultures 38 1.3 Conclusion 45 2 INTO THE BACK COUNTRY 56 2.1 Far West 58 2.2 Far East 73 2 .3 Kail 84 2.4 Back 96 3 THE QUEST MOTIF IN THE BACK COUNTRY 110 3.1 The Mythical Approach 110 3.1.1 Literature and Myth 110 3 .1. -

Climbing the Sea Annual Report

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG MARCH/APRIL 2015 • VOLUME 109 • NO. 2 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE Annual Report 2014 PAGE 3 Climbing the Sea sailing PAGE 23 tableofcontents Mar/Apr 2015 » Volume 109 » Number 2 The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. Features 3 Breakthrough The Mountaineers Annual Report 2014 23 Climbing the Sea a sailing experience 28 Sea Kayaking 23 a sport for everyone 30 National Trails Day celebrating the trails we love Columns 22 SUMMIT Savvy Guess that peak 29 MEMbER HIGHLIGHT Masako Nair 32 Nature’S WAy Western Bluebirds 34 RETRO REWIND Fred Beckey 36 PEAK FITNESS 30 Back-to-Backs Discover The Mountaineers Mountaineer magazine would like to thank The Mountaineers If you are thinking of joining — or have joined and aren’t sure where Foundation for its financial assistance. The Foundation operates to start — why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the as a separate organization from The Mountaineers, which has received about one-third of the Foundation’s gifts to various Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of nonprofit organizations. informational meetings at each of our seven branches. Mountaineer uses: CLEAR on the cover: Lori Stamper learning to sail. Sailing story on page 23. photographer: Alan Vogt AREA 2 the mountaineer magazine mar/apr 2015 THE MOUNTAINEERS ANNUAL REPORT 2014 FROM THE BOARD PRESIDENT Without individuals who appreciate the natural world and actively champion its preservation, we wouldn’t have the nearly 110 million acres of wilderness areas that we enjoy today. -

Select Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley

ENGLISH CLÀSSICS The vignette, representing Shelleÿs house at Great Mar lou) before the late alterations, is /ro m a water- colour drawing by Dina Williams, daughter of Shelleÿs friend Edward Williams, given to the E ditor by / . Bertrand Payne, Esq., and probably made about 1840. SELECT LETTERS OF PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY EDITED WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY RICHARD GARNETT NEW YORK D.APPLETON AND COMPANY X, 3, AND 5 BOND STREET MDCCCLXXXIII INTRODUCTION T he publication of a book in the series of which this little volume forms part, implies a claim on its behalf to a perfe&ion of form, as well as an attradiveness of subjeâ:, entitling it to the rank of a recognised English classic. This pretensión can rarely be advanced in favour of familiar letters, written in haste for the information or entertain ment of private friends. Such letters are frequently among the most delightful of literary compositions, but the stamp of absolute literary perfe&ion is rarely impressed upon them. The exceptions to this rule, in English literature at least, occur principally in the epistolary litera ture of the eighteenth century. Pope and Gray, artificial in their poetry, were not less artificial in genius to Cowper and Gray ; but would their un- their correspondence ; but while in the former premeditated utterances, from a literary point of department of composition they strove to display view, compare with the artifice of their prede their art, in the latter their no less successful cessors? The answer is not doubtful. Byron, endeavour was to conceal it. Together with Scott, and Kcats are excellent letter-writers, but Cowper and Walpole, they achieved the feat of their letters are far from possessing the classical imparting a literary value to ordinary topics by impress which they communicated to their poetry. -

Naked Lunch for Lawyers: William S. Burroughs on Capital Punishment

Batey: Naked LunchNAKED for Lawyers: LUNCH William FOR S. Burroughs LAWYERS: on Capital Punishme WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS ON CAPITAL PUNISHMENT, PORNOGRAPHY, THE DRUG TRADE, AND THE PREDATORY NATURE OF HUMAN INTERACTION t ROBERT BATEY* At eighty-two, William S. Burroughs has become a literary icon, "arguably the most influential American prose writer of the last 40 years,"' "the rebel spirit who has witch-doctored our culture and consciousness the most."2 In addition to literature, Burroughs' influence is discernible in contemporary music, art, filmmaking, and virtually any other endeavor that represents "what Newt Gingrich-a Burroughsian construct if ever there was one-likes to call the counterculture."3 Though Burroughs has produced a steady stream of books since the 1950's (including, most recently, a recollection of his dreams published in 1995 under the title My Education), Naked Lunch remains his masterpiece, a classic of twentieth century American fiction.4 Published in 1959' to t I would like to thank the students in my spring 1993 Law and Literature Seminar, to whom I assigned Naked Lunch, especially those who actually read it after I succumbed to fears of complaints and made the assignment optional. Their comments, as well as the ideas of Brian Bolton, a student in the spring 1994 seminar who chose Naked Lunch as the subject for his seminar paper, were particularly helpful in the gestation of this essay; I also benefited from the paper written on Naked Lunch by spring 1995 seminar student Christopher Dale. Gary Minda of Brooklyn Law School commented on an early draft of the essay, as did several Stetson University colleagues: John Cooper, Peter Lake, Terrill Poliman (now at Illinois), and Manuel Ramos (now at Tulane) of the College of Law, Michael Raymond of the English Department and Greg McCann of the School of Business Administration. -

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Sara Martín Alegre P08/04540/02135 © FUOC • P08/04540/02135 Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Index Introduction............................................................................................... 5 Objectives..................................................................................................... 7 1. Literature 1945-1990: cultural context........................................ 9 1.1. The book market in Britain ........................................................ 9 1.2. The relationship between Literature and the universities .......... 10 1.3. Adaptations of literary works for television and the cinema ...... 11 1.4. The minorities in English Literature: women and post-colonial writers .................................................................... 12 2. The English Novel 1945-1990.......................................................... 14 2.1. Traditionalism: between the past and the present ..................... 15 2.2. Fantasy, realism and experimentalism ........................................ 16 2.3. The post-modern novel .............................................................. 18 3. Drama in England 1945-1990......................................................... 21 3.1. West End theatre and the new English drama ........................... 21 3.2. Absurdist drama and social and political drama ........................ 22 3.3. New theatre companies and the Arts Council ............................ 23 3.4. Theatre from the mid-1960s onwards ....................................... -

Essay by Doug Jones on Bill Griffiths' Poetry

DOUG JONES “I ain’t anyone but you”: On Bill Griffths Bill Griffiths was found dead in bed, aged 59, on September 13, 2007. He had discharged himself from hospital a few days earlier after argu- ing with his doctors. I knew Griffiths from about 1997 to around 2002, a period where I was trying to write a dissertation on his poetry. I spent a lot of time with him then, corresponding and talking to him at length, always keen and pushing to get him to tell me what his poems were about. Of course, he never did. Don’ t think I ever got to know him, really. All this seems a lifetime ago. I’ m now a family physician (a general practitioner in the UK) in a coastal town in England. I’ ve taken a few days off from the COVID calamity and have some time to review the three-volume collection of his work published by Reality Street a few years ago. Volume 1 covers the early years, Volume 2 the 80s, and Volume 3 the period from his move to Seaham, County Durham in northeast England until his death. Here I should attempt do his work some justice, and give an idea, for an American readership, of its worth. Working up to this, I reread much of his poetry, works I hadn’ t properly touched in fifteen years. Going through it again after all that time, I was gobsmacked by its beauty, complexity, and how it continued to burn through a compla- cent and sequestered English poetry scene. -

Tarlo Tucker.Pdf

This is a repository copy of 'Off path, counter path’: contemporary walking collaborations in landscape, art and poetry. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/109131/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Tarlo, H and Tucker, J (2017) 'Off path, counter path’: contemporary walking collaborations in landscape, art and poetry. Critical Survey, 29 (1). pp. 105-132. ISSN 0011-1570 https://doi.org/10.3167/cs.2017.290107 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Harriet Tarlo and Judith Tucker ‘Off path, counter path’: contemporary walking collaborations in landscape, art and poetry Our title reflects our tendency as walkers and collaborators to wander off the established path through a series of negotiations and diversions. In this jointly-authored essay by a poet and an artist, we ask whether and how this companionable and artistic process might also be counter- cultural, as many anecdotal and theoretical enframings of walking practice throughout the centuries have suggested. -

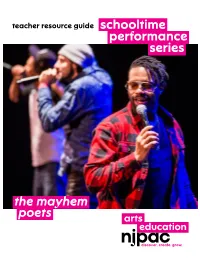

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

165Richard.Pdf

165 165 c2001 Richard Caddel Basil Basil Bunting : An Introduction to to a Northern Modernist Poet : The Interweaving Voices of Oppositional Poetry Richard Richard Caddel I'd I'd like to thank the Institute of Oriental and Occidental Studies for inviting me to give this this presentation, and for their generosity in sustaining me throughout this fellowship. I have have to say that I feel a little intimidated by my task here, which is to present the work of of a poet who is still far from well known in his own country, and who many regard as not not an easy poet (is there such a thing?) in an environment to which both he and I are foreign. foreign. This is my first visit to your country, and Bunting, though he travelled widely throughout throughout his life, never came here. That's a pity, because early in his poetic career he made what I consider to be a very effective English poem out of the Japanese prose classic, classic, Kamo no Chomei's Hojoki (albeit from an Italian tranlation, rather than the original) original) and I think he had the temperament to have enjoyed himself greatly here. I'm I'm going to present him, as much as possible, in his own words, often using recordings of him reading. He read well, and his poetry has a direct physical appeal which makes my task task of presenting it a pleasure, and I hope this approach will be useful for you as well. But first a few introductory words will be necessary. -

Modernist Poetry

GRAAT On-Line issue #8 August 2010 The unquiet boundary, or the footnote Auto-exegetic modes in (neo-)modernist poetry Lucie Boukalova University of Northern Iowa “It is generally supposed that where there is no QUOTATION, there will be found most originality. Our writers usually furnish their pages rapidly with the productions of their own soil: they run up a quickset hedge, or plant a poplar, and get trees and hedges of this fashion much faster than the former landlords procured their timber. The greater part of our writers, in consequence, have become so original, that no one cares to imitate them; and those who never quote, in return are seldom quoted!” Isaac Disraeli, Curiosities of Literature “I have been accused of wanting to make people read all the classics; which is not so. I have been accused of wishing to provide a „portable substitute for the British Museum,‟ which I would do, like a shot, were it possible. It isn‟t.” Ezra Pound, How to Read Clearly unhappy with the course of the scholarly treatment of his notes to The Waste Land, T.S. Eliot revisits the exegetical site three decades after the modernist annus mirabilis in “The Frontiers of Criticism” (1956). Even though he acknowledges that he is not wholly “guiltless of having led critics into temptation” by his annotation, and even though he regrets “having sent so many enquirers off on a wild goose chase,”1 the poet does not publicly condemn his previous method. Retracing and reinforcing the frontiers of a profitable critical enterprise, Eliot calls for a more immediate, and intuitive interaction between the poetic lines and their “paratext.”2 115 However, thus still defending the aesthetic value of his referential apparatus, Eliot seems to have lost faith in the continuity of such practice in the contemporary creative and critical climate. -

Oral History Interview with Karl Drerup, 1974 November 15-1975 January 28

Oral history interview with Karl Drerup, 1974 November 15-1975 January 28 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Karl Drerup on November 15, 1974 and January 28, 1975. The interview was conducted in Thornton, NH by Robert Brown for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ROBERT BROWN: This is an interview in Thornton, New Hampshire in November 15, 1974 with Karl Drerup and I would like to begin by—if you will talk a bit about your childhood. I know your family was a very old one in Westphalia [Germany] and if you could give some feeling of your family as you knew them and some of the memories of your earlier childhood. KARL DRERUP: All right. A very strictly orthodox Roman Catholic family to begin with. This is one of the main elements of my terribly religious middle-class shelter, if you wish. Ja, this would be a good description. Of course, First World War fell into my time, into my youth. ROBERT BROWN: You were about 10 when it started; weren't you? KARL DRERUP: Yeah, and we saw the army go out on horseback and come back on horseback you might say is what happened—during the war, my mother's and my stepfather's particular interests were to have one of their children become a clergyman. -

Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics

Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics Series Editor Rachel Blau DuPlessis Temple University Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics promotes and pursues topics in the burgeoning field of 20th and 21st century poetics. Critical and scholarly work on poetry and poetics of interest to the series includes social location in its relationships to subjectivity, to the construction of authorship, to oeuvres, and to careers; poetic reception and dissemination (groups, movements, formations, institutions); the intersection of poetry and theory; questions about language, poetic authority, and the goals of writing; claims in poetics, impacts of social life, and the dynamics of the poetic career as these are staged and debated by poets and inside poems. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14799 Luke Roberts Barry MacSweeney and the Politics of Post-War British Poetry Seditious Things Luke Roberts King’s College London London, United Kingdom Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics ISBN 978-3-319-45957-8 ISBN 978-3-319-45958-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-45958-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017930177 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.