(1800-1893) and Others Yet Unrecorded?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRUIDOSOFIA Libro VIII De Druidosofía Espiritualidad Y Teología Druídica Conceptos Sobre La Divinidad Iolair Faol

DRUIDOSOFIA Libro VIII De Druidosofía Espiritualidad Y Teología Druídica Conceptos sobre La Divinidad Iolair Faol Nota sobre las imágenes: Las imágenes de este libro han sido están tomadas de Internet. En ninguna de ellas constaba autor o copyright. No obstante, si el autor de alguna de ellas, piensa que sus derechos son vulnerados, y desea que no aparezcan en este libro, le ruego, se ponga contacto con [email protected] Gracias. Todas las imágenes pertenecen a sus legítimos autores. Nota sobre el texto: En cualquier punto del presente libro se pueden usar indistintamente, tanto términos masculinos como femeninos para designar al género humano e incluso el uso del vocablo “druidas” “bardos”, “vates”, etc., para designar tanto a los hombres como a las mujeres que practican esta espiritualidad, especialidades o funciones. El autor desea recalcar que su uso no obedece a una discriminación sexista, sino que su empleo es para facilitar la fluidez en la lectura, englobando en los términos a ambos sexos por igual. Iolair Faol Está permitida la reproducción parcial de este libro, por cualquier medio o procedimiento, siempre que se cite la fuente de donde se extrajo y al autor del presente libro. Para la reproducción total de este libro, póngase en contacto con el autor o con la persona que posea los derechos del Copyright. El autor desea hacer constar que existen por Internet, muchas webs y blogs, que han usado total o parcialmente, capítulos enteros de éste u otros libros y escritos varios del autor, sin respetar la propiedad intelectual, sin citar autorías, ni reconocer los esfuerzos de ningún autor. -

The Height of Its Womanhood': Women and Genderin Welsh Nationalism, 1847-1945

'The height of its womanhood': Women and genderin Welsh nationalism, 1847-1945 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kreider, Jodie Alysa Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 04:59:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280621 'THE HEIGHT OF ITS WOMANHOOD': WOMEN AND GENDER IN WELSH NATIONALISM, 1847-1945 by Jodie Alysa Kreider Copyright © Jodie Alysa Kreider 2004 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partia' Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2004 UMI Number: 3145085 Copyright 2004 by Kreider, Jodie Alysa All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3145085 Copyright 2004 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

Herefore the Hereditary Lineage Ceased

Countryside access and walking VALEWAYS Cerdded yng nghefn gwlad Newsletter Summer 2019 W elcome to the Valeways Summer Newsletter and what better way to find out ‘What’s occurring’ this summer than with pictures by the artist Haf Weighton. Having lived and worked in London for many years, exhibiting widely in galleries including Alexandra Palace and The Saatchi Gallery, Haf (literally translated as Summer) recently returned to South Wales and has settled in Penarth. It is no wonder that her recent exhibition at the Penarth Pier Gallery was entitled ‘Adref – Home’. A dref / Home included the featured artworks entitled ‘Shore Penarth’ and ’Beach Cliff, Penarth’ and are two in a series of four based on Haf’s involvement with a campaign group set up to fight proposals by the Vale of Glamorgan Council to replace all Penarth’s characteristic Victorian lamp posts with modern ones. Although the plans do not include The Esplanade, 21 streets listed, including Railway Terrace, Archer Place and Dingle Road will be affected and Haf has included their names in her work – something to look out for on the next walk around Penarth. We are indebted to Haf for allowing us to reproduce these examples of her work. For more information about Haf and her work please visit hafanhaf.com What’s in a name? Romilly, Egerton Grey, Llwyneliddon,(St Lythans) Llandochau Fach, Ystradowen, Whitmore and Jackson, Waitrose… and many more are not only names reflecting the Vale’s varied past but also continue to provide rich fodder for our modern day explorations – well, maybe not Waitrose. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

3 Celtic Crosses and Coast Walk Online Leaflet English

VALE OF GLAMORGAN Approximate walk time: 2 hours COAST • COUNTRYSIDE • CULTURE WALKING IN THE VALE ARFORDIR • CEFN GWLAD • DIWYLLIANT BRO MORGANNWG Walking in the Vale of Glamorgan combines a fascinating 60 km stretch of the Wales Coast Path with THE COUNTRYSIDE CODE the picturesque, historic beauty of inland Vale. Along its VALE OF GLAMORGAN VALE OF GLAMORGAN VALE OF GLAMORGAN VALE OF GLAMORGAN VALE OF GLAMORGAN • Be safe – plan ahead and follow any signs. COAST • COUNTRYSIDE • CULTURE COAST • COUNTRYSIDE • CULTURE COAST • COUNTRYSIDE • CULTURErugged coastlineCOAST • COUNTRYSIDE walkers • CULTURE can discoverCOAST the • COUNTRYSIDE last manned • CULTURE lighthouse in Wales (automated as recently as 1998), • Leave gates and property as you find them. Celtic Crosses a college unlike any other at St. Donats and 16th Century • Protect plants and animals, and take your litter home. walled gardens at Dunraven Bay, plus the seaside bustle • Keep dogs under close control. ARFORDIR • CEFN GWLAD • DIWYLLIANT ARFORDIR • CEFN GWLAD • DIWYLLIANT ARFORDIR • CEFN GWLAD • DIWYLLIANofT Barry ARFORDIRand Penarth. • CEFN GWLAD • DIWYLLIANWhicheverT directionARFORDIR • CEFN you GWLA Dare • DIWYLLIAN T • Consider other people. BRO MORGANNWG BRO MORGANNWG BRO MORGANNWG BRO MORGANNWG BRO MORGANNWG and Coast Walk walking look for at regular points along the way. Inland, walkers will find the historic market towns of Cowbridge and Llantwit Major, as well as idyllic villages Llantwit Major and Surrounding Area Walk such as St. Nicholas and St. Brides Major, where the Footpaths / Llwybrau Bridleway / Llwybr ceffyl (3 miles / 5 km) plus 2 mile / 3.2 km optional walk story of the Vale is told through monuments such as Restricted Byway / Cilffordd gyfyngedig Byway / Cilffordd Tinkinswood burial chamber and local characters like Iolo Morganwg, one of the architects of the Welsh nation. -

Trilithon E Journal of Scholarship and the Arts of the Ancient Order of Druids in America

Trilithon e Journal of Scholarship and the Arts of the Ancient Order of Druids in America Volume VI Winter Solstice, 2019 Copyright 2019 by the Ancient Order of Druids in America, Indiana, Pennsylvania. (www.aoda.org) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. ISBN-13: 978-1-7343456-0-5 Colophon Cover art by Dana O’Driscoll Designed by Robert Pacitti using Adobe® InDesign.® Contents Editor’s Introduction....................................................................................................I Letter from the New Grand Archdruid: Into the Future of AODA............................1 Dana O’Driscoll Urban Druidry: e Cauldron of the City..................................................................6 Erin Rose Conner Interconnected and Interdependent: e Transformative Power of Books on the Druid Path...........................................................................................................14 Kathleen Opon A Just City.................................................................................................................24 Gordon S. Cooper e City and the Druid.............................................................................................28 Moine -

Eisteddfod Handout Prepared for Ninth Welsh Weekend for Everyone by Marilyn Schrader

Eisteddfod handout prepared for Ninth Welsh Weekend for Everyone by Marilyn Schrader An eisteddfod is a Welsh festival of literature, music and performance. The tradition of such a meeting of Welsh artists dates back to at least the 12th century, when a festival of poetry and music was held by Rhys ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth at his court in Cardigan in 1176 but, with the decline of the bardic tradition, it fell into abeyance. The present-day format owes much to an eighteenth-century revival arising out of a number of informal eisteddfodau. The date of the first eisteddfod is a matter of much debate among scholars, but boards for the judging of poetry definitely existed in Wales from at least as early as the twelfth century, and it is likely that the ancient Celtic bards had formalized ways of judging poetry as well. The first eisteddfod can be traced back to 1176, under the auspices of Lord Rhys, at his castle in Cardigan. There he held a grand gathering to which were invited poets and musicians from all over the country. A chair at the Lord's table was awarded to the best poet and musician, a tradition that prevails in the modern day National Eisteddfod. The earliest large-scale eisteddfod that can be proven beyond all doubt to have taken place, however, was the Carmarthen Eisteddfod, which took place in 1451. The next recorded large-scale eisteddfod was held in Caerwys in 1568. The prizes awarded were a miniature silver chair to the successful poet, a little silver crwth to the winning fiddler, a silver tongue to the best singer, and a tiny silver harp to the best harpist. -

BCUHB Annual Report 2013

Betsi Cadwaladr University Local Health Board Annual Report and Accounts 2012/13 Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board - Annual Report and Accounts 2012/13 1 Contents About the Health Board 4 Making it Better 31 Service User Experience 31 Achievements & Awards 5 Modernisation & Service Improvement 32 Principles of Remedy 33 Making it Safe 7 Welsh Language 34 Quality and Safety 7 Equality, Diversity & Human Rights 34 Keeping People Safe 9 Research and Learning 35 Keeping Information Safe 9 Monitoring Standards for Health Services 37 Ready for an Emergency 11 Public Health 37 Making it Work 12 Making it Sound 40 Our Workforce 12 Statement of Accountable Officer’s Caring for our Staff 13 Responsibilities 40 Engaging and Communicating with Staff 15 Governance and Quality Statement 40 Estates and Infrastructure 16 Risk Management 41 Our Board 41 Making it Happen 19 Directors’ Declarations of Interest 43 Performance & Financial Review 19 Primary Financial Statements and Notes 44 Our Environmental and Social Remuneration Report 49 Commitments 22 Auditors’ Report 56 Primary Care and Localities 26 Engagement and Consultation 28 Working with our Partners 29 Organisational Development 30 Welcome from the Chairman and Acting Chief Executive Welcome to the Annual Report for Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board for 2012/13. The past year has been a challenging one for the Health Board as we seek to deliver improvements in the services and care we provide, whilst ensuring that they are safe and sustainable within the resources that we have available to us. Yet again we can report excellent achievements by our staff, and those who work in primary care. -

Jane Williams (Ysgafell) (1806-85) and Nineteenth-Century Welsh Identity

Gwyneth Tyson Roberts Department of English and Creative Writing Thesis title: Jane Williams (Ysgafell) (1806-85) and nineteenth-century Welsh identity SUMMARY This thesis examines the life and work of Jane Williams (Ysgafell) and her relation to nineteenth-century Welsh identity and Welsh culture. Williams's writing career spanned more than fifty years and she worked in a wide range of genres (poetry, history, biography, literary criticism, a critique of an official report on education in Wales, a memoir of childhood, and religious tracts). She lived in Wales for much of her life and drew on Welsh, and Welsh- language, sources for much of her published writing. Her body of work has hitherto received no detailed critical attention, however, and this thesis considers the ways in which her gender and the variety of genres in which she wrote (several of which were genres in which women rarely operated at that period) have contributed to the omission of her work from the field of Welsh Writing in English. The thesis argues that this critical neglect demonstrates the current limitations of this academic field. The thesis considers Williams's body of work by analysing the ways in which she positioned herself in relation to Wales, and therefore reconstructs her biography (current accounts of much of her life are inaccurate or misleading) in order to trace not only the general trajectory of this affective relation, but also to examine the variations and nuances of this relation in each of her published works. The study argues that the liminality of Jane Williams's position, in both her life and work, corresponds closely to many of the important features of the established canon of Welsh Writing in English. -

Minutes Pdf 391 Kb

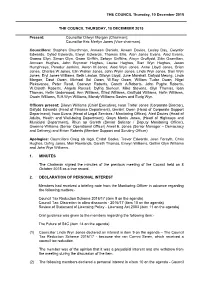

THE COUNCIL Thursday, 10 December 2015 THE COUNCIL THURSDAY, 10 DECEMBER 2015 Present: Councillor Dilwyn Morgan (Chairman); Councillor Eric Merfyn Jones (Vice-chairman). Councillors: Stephen Churchman, Annwen Daniels, Anwen Davies, Lesley Day, Gwynfor Edwards, Dyfed Edwards, Elwyn Edwards, Thomas Ellis, Alan Jones Evans, Aled Evans, Gweno Glyn, Simon Glyn, Gwen Griffith, Selwyn Griffiths, Alwyn Gruffydd, Siân Gwenllian, Annwen Hughes, John Brynmor Hughes, Louise Hughes, Sian Wyn Hughes, Jason Humphreys, Peredur Jenkins, Aeron M.Jones, Aled Wyn Jones, Anne Lloyd Jones, Brian Jones, Charles W.Jones, Elin Walker Jones, John Wynn Jones, Linda Wyn Jones, Sion Wyn Jones, Eryl Jones-Williams, Beth Lawton, Dilwyn Lloyd, June Marshall, Dafydd Meurig, Linda Morgan, Dewi Owen, Michael Sol Owen, W.Roy Owen, William Tudor Owen, Nigel Pickavance, Peter Read, Caerwyn Roberts, Gareth A.Roberts, John Pughe Roberts, W.Gareth Roberts, Angela Russell, Dyfrig Siencyn, Mike Stevens, Glyn Thomas, Ioan Thomas, Hefin Underwood, Ann Williams, Elfed Williams, Gruffydd Williams, Hefin Williams, Owain Williams, R.H.Wyn Williams, Mandy Williams-Davies and Eurig Wyn. Officers present: Dilwyn Williams (Chief Executive), Iwan Trefor Jones (Corporate Director), Dafydd Edwards (Head of Finance Department), Geraint Owen (Head of Corporate Support Department), Iwan Evans (Head of Legal Services / Monitoring Officer), Aled Davies (Head of Adults, Health and Well-being Department), Gwyn Morris Jones, (Head of Highways and Municipal Department), Rhun ap Gareth (Senior Solicitor / Deputy Monitoring Officer), Gwenno Williams (Senior Operational Officer) Arwel E. Jones (Senior Manager – Democracy and Delivery) and Eirian Roberts (Member Support and Scrutiny Officer). Apologies: Councillors Craig ab Iago, Endaf Cooke, Trevor Edwards, Jean Forsyth, Chris Hughes, Dyfrig Jones, Mair Rowlands, Gareth Thomas, Eirwyn Williams, Gethin Glyn Williams and John Wyn Williams. -

Inspiring Patagonia

+ Philip Pullman Growing up in Ardudwy John Osmond Where stand the parties now Inspiring Gerald Holtham Time to be bold on the economy Ned Thomas Patagonia Cultural corridor to the east Sarah Jenkinson A forest the size of Wales Gareth Rees The PISA moral panic Virginia Isaac Small is still beautiful Mari Beynon Owen Wales at the Venice Biennale Trevor Fishlock Memories are made of this Peter Finch Joining a thousand literary flowers together Peter Stead The Burton global phenomenon www.iwa.org.uk | Summer 2011 | No. 44 | £10 The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges funding support from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation. The following organisations are corporate members: Private Sector • Nuon Renewables • Cyngor Gwynedd Council • UWIC Business School • A4E • OCR Cymru • Cyngor Ynys Mon / Isle of • Wales Audit Office • ABACA Limited • Ove Arup & Partners Anglesey County Council • WLGA • Alchemy Wealth • Parker Plant Hire Ltd • Embassy of Ireland • WRAP Cymru Management Ltd • Peter Gill & Associates • Environment Agency Wales • Ystrad Mynach College • Arden Kitt Associates Ltd • PricewaterhouseCoopers • EVAD Trust • Association of Chartered • Princes Gate Spring Water • Fforwm Certified Accountants • RMG • Forestry Commission Voluntary Sector (ACCA) • Royal Mail Group Wales • Gower College Swansea • Age Cymru • Beaufort Research Ltd • RWE NPower Renewables • Harvard College Library • All Wales Ethnic Minority • British Gas • S A Brain & Co • Heritage Lottery Fund -

UWB Ann Review 2005

UWB Annual Review 2006:UWB Annual Review 2005 31/1/07 09:26 Page 1 ANNUAL REVIEW 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005-2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 University of Wales, Bangor UWB Annual Review 2006:UWB Annual Review 2005 31/1/07 09:26 Page 2 2 Annual Review 2005 - 2006 A word from the VICE-CHANCELLOR he period covered by this marks another very significant milestone “T annual review has been one of in our history. significant development, and we are now well positioned to move forward We have brought our academic schools against some very tough competition together by creating six new Colleges, from other universities within the UK which will become a focus for greater and internationally. collaboration in many areas, but especially research and teaching. Together, we have achieved a tremendous amount over the last year. One of the biggest challenges we face is Reflecting on some of these successes in relation to our estate. Our staff, students illustrates just how far we’ve travelled and visitors all expect high quality in such a short period of time. buildings in which to work and study, and we’re already well on the way towards Excellence is the overarching theme of making our facilities fit for the future. A our strategic plan, and we are investing number of ambitious developments are heavily to achieve our aims. By careful currently taking shape around the management we have improved the campus. Further developments are University’s financial position during the planned over the next few years as part last year and this has allowed us to of an ambitious Estates Strategy which invest in key areas.