Untold Case Studies of World War I German Internment Jacob L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100 Percent Americanism in the Concert Hall: the Minneapolis Symphony in the Great War

100 Percent Americanism in the Concert Hall: The Minneapolis Symphony in the Great War Michael J. Pfeifer In 1918 a Minnesota music critic assessed a Minneapolis Symphony concert warmly, noting that the orchestra’s recent “racial house-cleansing” – a purge of some of the orchestra’s German and Austrian-born musicians – had not com- promised the quality of the ensemble’s playing. While the critic believed that “like gasoline and whiskey, music and war really ought not to have anything in particular to do with each other”, he nonetheless judged it well worthwhile from a “standpoint of musical interest” to hear the orchestra “magnificently” perform the national anthems of the Allied nations that opened the concert. Earlier, at the beginning of the 1918–1919 season, members of the Minneapolis Symphony had been required to sign loyalty oaths to the United States, while a cellist had been compelled to leave the orchestra for a period because he sup- posedly had hung portraits of the Kaiser and his wife over his fireplace (these were actually pictures of “the deceased Austrian emperor Franz Josef and his wife”).1 While the Minneapolis Symphony and its Munich-born founder Emil Oberhoffer (1867–1933) did not encounter the extreme repercussions that led to the arrest, internment, and deportation of Karl Muck (1859–1940) and Ernst Kunwald (1868–1939), respectively the German and Austrian conductors of the Boston Symphony and the Cincinnati Symphony,2 a significant nativist, anti- German, backlash did mark the orchestra’s experience of the latter years of the Great War. The upper Midwestern state of Minnesota was substantially German in nativity and ancestry at the outbreak of the war, which may have mitigated some of the harshly jingoistic reaction that German symphonic * I am grateful to Frank Jacob and William H. -

ARSC Journal, Vol.21, No

Sound Recording Reviews Wagner: Parsifal (excerpts). Berlin State Opera Chorus and Orchestra (a) Bayreuth Festival Chorus and Orchestra (b), cond. Karl Muck. Opal 837/8 (LP; mono). Prelude (a: December 11, 1927); Act 1-Transformation & Grail Scenes (b: July/ August, 1927); Act 2-Flower Maidens' Scene (b: July/August, 1927); Act 3 (a: with G. Pistor, C. Bronsgeest, L. Hofmann; slightly abridged; October 10-11and13-14, 1928). Karl Muck conducted Parsifal at every Bayreuth Festival from 1901 to 1930. His immediate predecessor was Franz Fischer, the Munich conductor who had alternated with Hermann Levi during the premiere season of 1882 under Wagner's own supervi sion. And Muck's retirement, soon after Cosima and Siegfried Wagner died, brought another changing of the guard; Wilhelm Furtwangler came to the Green Hill for the next festival, at which Parsifal was controversially assigned to Arturo Toscanini. It is difficult if not impossible to tell how far Muck's interpretation of Parsifal reflected traditions originating with Wagner himself. Muck's act-by-act timings from 1901 mostly fall within the range defined in 1882 by Levi and Fischer, but Act 1 was decidedly slower-1:56, compared with Levi's 1:47 and Fischer's 1:50. Muck's timing is closer to that of Felix Mottl, who had been a musical assistant in 1882, and of Hans Knappertsbusch in his first and slowest Bayreuth Parsifal. But in later summers Muck speeded up to the more "normal" timings of 1:50 and 1:47, and the extensive recordings he made in 1927-8, now republished by Opal, show that he could be not only "sehr langsam" but also "bewegt," according to the score's requirements. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 35,1915-1916, Trip

SANDERS THEATRE . CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY ^\^><i Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor ITTr WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE THURSDAY EVENING, MARCH 23 AT 8.00 COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER 1 €$ Yes, It's a Steinway ISN'T there supreme satisfaction in being able to say that of the piano in your home? Would you have the same feeling about any other piano? " It's a Steinway." Nothing more need be said. Everybody knows you have chosen wisely; you have given to your home the very best that money can buy. You will never even think of changing this piano for any other. As the years go by the words "It's a Steinway" will mean more and more to I you. and thousands of times, as you continue to enjoy through life the com- panionship of that noble instrument, absolutely without a peer, you will say to yourself: "How glad I am I paid the few extra dollars and got a Steinway." pw=a I»3 ^a STEINWAY HALL 107-109 East 14th Street, New York Subway Express Station at the Door Represented by the Foremost Dealers Everywhere Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Violins. Witek, A. Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Rissland, K. Concert-master. Koessler, M. Schmidt, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noack, S. Mahn, F. Bak, A. Traupe, W. Goldstein, H. Tak, E. Ribarsch, A. Baraniecki, A. Sauvlet. H. Habenicht, W. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Goldstein, S. Fiumara, P. Spoor, S. Sulzen, H. -

The Allied Powers; the Central What Did Citizens Think the U.S

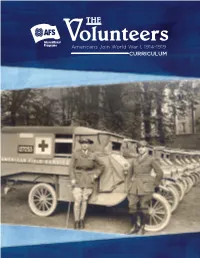

Connecting lives. Sharing cultures. Dear Educator, Welcome to The Volunteers: Americans Join World War I, 1914-1919 Curriculum! Please join us in celebrating the release of this unique and relevant curriculum about U.S. American volunteers in World War I and how volunteerism is a key component of global competence and active citizenship education today. These free, Common Core and UNESCO Global Learning-aligned secondary school lesson plans explore the motivations behind why people volunteer. They also examine character- istics of humanitarian organizations, and encourage young people to consider volunteering today. AFS Intercultural Programs created this curriculum in part to commemorate the 100 year history of AFS, founded in 1915 as a volunteer U.S. American ambulance corps serving alongside the French military during the period of U.S. neutrality. Today, AFS Intercultural Programs is a non-profit, intercultural learn- ing and student exchange organization dedicated to creating active global citizens in today’s world. The curriculum was created by AFS Intercultural Programs, together with a distinguished Curriculum Development Committee of historians, educators, and archivists. The lesson plans were developed in partnership with the National World War I Museum and Memorial and the curriculum specialists at Pri- mary Source, a non-profit resource center dedicated to advancing global education. We are honored to have received endorsement for the project from the United States World War I Centennial Commission. We would like to thank the AFS volunteers, staff, educators, and many others who have supported the development of this curriculum and whose daily work advances the AFS mission. We encourage sec- ondary school teachers around the world to adapt these lesson plans to fit their classroom needs- les- sons can be applied in many different national contexts. -

Presidential Documents

Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents Monday, September 29, 1997 Volume 33ÐNumber 39 Pages 1371±1429 1 VerDate 22-AUG-97 07:53 Oct 01, 1997 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 1249 Sfmt 1249 W:\DISC\P39SE4.000 p39se4 Contents Addresses and Remarks Communications to CongressÐContinued See also Meetings With Foreign Leaders Future free trade area negotiations, letter Arkansas, Little Rock transmitting reportÐ1423 Congressional Medal of Honor Society India-U.S. extradition treaty and receptionÐ1419 documentation, message transmittingÐ1401 40th anniversary of the desegregation of Iraq, letter reportingÐ1397 Central High SchoolÐ1416 Ireland-U.S. taxation convention and protocol, California message transmittingÐ1414 San Carlos, roundtable discussion at the UNITA, message transmitting noticeÐ1414 San Carlos Charter Learning CenterÐ 1372 Communications to Federal Agencies San Francisco Contributions to the International Fund for Democratic National Committee Ireland, memorandumÐ1396 dinnerÐ1382 Funding for the African Crisis Response Democratic National Committee luncheonÐ1376 Initiative, memorandumÐ1397 Saxophone Club receptionÐ1378 Interviews With the News Media New York City, United Nations Exchange with reporters at the United LuncheonÐ1395 Nations in New York CityÐ1395 52d Session of the General AssemblyÐ1386 Interview on the Tom Joyner Morning Show Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh in Little RockÐ1423 AFL±CIO conventionÐ1401 Democratic National Committee luncheonÐ1408 Letters and Messages Radio addressÐ1371 50th anniversary of the National Security Council, messageÐ1396 Communications to Congress Meetings With Foreign Leaders Angola, message reportingÐ1414 Russia, Foreign Minister PrimakovÐ1395 Canada-U.S. taxation convention protocol, message transmittingÐ1400 Notices Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty and Continuation of Emergency With Respect to documentation, message transmittingÐ1390 UNITAÐ1413 (Continued on the inside of the back cover.) Editor's Note: The President was in Little Rock, AR, on September 26, the closing date of this issue. -

Yankees Who Fought for the Maple Leaf: a History of the American Citizens

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 12-1-1997 Yankees who fought for the maple leaf: A history of the American citizens who enlisted voluntarily and served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force before the United States of America entered the First World War, 1914-1917 T J. Harris University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Harris, T J., "Yankees who fought for the maple leaf: A history of the American citizens who enlisted voluntarily and served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force before the United States of America entered the First World War, 1914-1917" (1997). Student Work. 364. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/364 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Yankees Who Fought For The Maple Leaf’ A History of the American Citizens Who Enlisted Voluntarily and Served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force Before the United States of America Entered the First World War, 1914-1917. A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts University of Nebraska at Omaha by T. J. Harris December 1997 UMI Number: EP73002 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 32,1912-1913, Trip

INFANTRY HALL • PROVIDENCE Thirty-second Season, J9J2—X9J3 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Programme of % THIRD CONCERT WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE TUESDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 31 AT 8.15 COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER — " After the Symphony Concert 9J a prolonging of musical pleasure by home-firelight awaits the owner of a "Baldwin." The strongest impressions of the concert season are linked with Baldwintone, exquisitely exploited by pianists eminent in their art. Schnitzer, Pugno, Scharwenka, Bachaus De Pachmann! More than chance attracts the finely-gifted amateur to this keyboard. Among people who love good music, who have a culti- vated knowledge of it, and who seek the best medium for producing it, the Baldwin is chief. In such an atmosphere it is as happily "at home" as are the Preludes of Chopin, the Liszt Rhapsodies upon a virtuoso's programme. THE BOOK OF THE BALDWIN free upon request. Sole Representative MRS. LUCY H. MILLER 28 GEORGE STREET - - PROVIDENCE, R.I. Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL Thirty-second Season, 1912-1913 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Violins. Witek, A., Roth, 0. Hoffmann, J. Mahn, F. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Tak, E. Theodorowicz, J. Strube, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W. Koessler, M. Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Goldstein, H. Habenicht, W. Akeroyd, J. Spoor, S. Berger, H. Fiumara, P. Fiedler, B. Marble, E. Hayne, E. Tischer-Zeitz, H Kurth, R. Grunberg, M. Goldstein, S. Pinfield, C. E. Gerardi, A. Violas. Ferir, E. Werner, H. Pauer, 0. H. Kluge, M. Van Wynbergen, C Gietzen, A. -

The Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa, Music Director & Conductor Peter Serkin, Piano

PETER LIEBERSON New World Records 80325 Piano Concerto The Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa, music director & conductor Peter Serkin, piano Peter Lieberson was born in New York City on October 25, 1946; he lives in Newton Center, Massachusetts, and is currently teaching at Harvard. His Piano Concerto is one of twelve works commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra for its centennial in 1981. From the beginning the piano solo part was intended for Peter Serkin, who gave the first performance with Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony Orchestra on April 21, 1983, in Symphony Hall, Boston. The youngest of the 12 composers commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra for its centennial, Peter Lieberson grew up in a family where music was ubiquitous. Both his parents were important figures in the artistic world. His father, Goddard Lieberson, himself a trained composer, was perhaps best known as the most influential record-company executive in the artistic world. Peter's mother, under the stage name Vera Zorina, was a ballerina with the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo and later with George Balanchine, before she became known as a specialist in spoken narration. Through a job at New York's classical music radio station WNCN, Lieberson came to know Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson. But the crucial connection came when Copland invited Milton Babbitt to do a program. Until that time the major influence on Lieberson's music was Stravinsky. Now he began to study informally with Babbitt. At Babbitt's suggestion Lieberson chose Columbia when he decided to pursue graduate studies; there he worked with Charles Wuorinen (the third of his three principal teachers would be Donald Martino, with whom he studied at Brandeis University). -

Women's Places in the New Laboratories Of

Repositorium für die Geschlechterforschung Women’s Places in the New Laboratories of Biological Research in the 20th century: Gender, Work and the Dynamics of Science Satzinger, Helga 2004 https://doi.org/10.25595/246 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Satzinger, Helga: Women’s Places in the New Laboratories of Biological Research in the 20th century: Gender, Work and the Dynamics of Science, in: Štrbá#ová, So#a; Stamhuis, Ida H.; Mojsejová, Kate#ina (Hrsg.): Women Scholars and Institutions. Proceedings of the International Conference (Prague: Výzkumné centrum pro d#jiny v#dy, 2004), 265-294. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25595/246. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY 4.0 Lizenz (Namensnennung) This document is made available under a CC BY 4.0 License zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden (Attribution). For more information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de www.genderopen.de WOMEN SCHOLARS AND INSTITUTIONS WOMEN'S PLACES NEW LABORATORIES GENETIC RESEARCH EARLY 20TH CENTURY: GENDER, WORK, THE DYNAMICS Helga Satzinger Abstract In genetic research of the first decades of the 20'" century women's work became a substantial resource. Women worked at different positions in scientific institutions; as independent scientists, wives of leading scientist, and as technical or other assistants. Male and female scientists had different opportunities to draw on the workforce of others; mostly women were doing the routine experimental work in the laboratories. This difference was crucial for the scientists' choice experimental systems. -

Have German Will Travel Feiertag

HAVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL FEIERTAG "Bei uns ist immer was los!" AUSTRIAN-AMERICAN DAY: der 26. September W ILLIAM J. CLINTON XUJ Pmidmtoftht Uniud Sltlte: 1993-2001 Proclamation 7027- Austrian-American Day, 1997 September 25. 1997 By the President of the United States ofAmerica A Proclamation For more than 2.00 years, the life of our Nation has been enriched and renewed by the many people who have come here from around the world, s~oeking a new life for Lhcmsclvcs aod their families. Austrian America us have made their own unique and lastiug contributions to America's strength and character, and they contin,l<ltO play a vital role in tho peace and prosperity we enjoy today. As with so many other immigrants, the e.1ruest Austrians came to America in search of religious freedom. Arrhing in 1734, they settled in the colony of Georgia, f.TOwing and pros pering with the passing of the years. One of these early Austrian settlers, J ohann Adam Treutleo, was to become the Hrs t elected go-nor of the new State of Georgia. lJlthe two ecoturies that foUowed, millions of other Austrians made the same journey to our shores. From the political refugees o f the 1848 re>-olutions in Austria to Jews Oceing the anti-Semitism of Hitler's Third Reich, Austrians brought ";th them to America a lo\e of freedom, a strong work ethic, and a deep re--erence for educatioiL In C\'Cf'Y fldd of endeavor, Austrian Americans ha\'C made notable contributions to our culture and society. -

CHAPTER 1 SPECIAL AGENTS, SPECIAL THREATS: Creating the Office of the Chief Special Agent, 1914-1933

CHAPTER 1 SPECIAL AGENTS, SPECIAL THREATS: Creating the Office of the Chief Special Agent, 1914-1933 CHAPTER 1 8 SPECIAL AGENTS, SPECIAL THREATS Creating the Office of the Chief Special Agent, 1914-1933 World War I created a diplomatic security crisis for the United States. Under Secretary of State Joseph C. Grew afterwards would describe the era before the war as “diplomatic serenity – a fool’s paradise.” In retrospect, Grew’s observation indicates more the degree to which World War I altered how U.S. officials perceived diplomatic security than the actual state of pre-war security.1 During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Department had developed an effective set of security measures; however, those measures were developed during a long era of trans-Atlantic peace (there had been no major multi-national wars since Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1814). Moreover, those measures were developed for a nation that was a regional power, not a world power exercising influence in multiple parts of the world. World War I fundamentally altered international politics, global economics, and diplomatic relations and thrust the United States onto the world stage as a key world power. Consequently, U.S. policymakers and diplomats developed a profound sense of insecurity regarding the content of U.S. Government information. The sharp contrast between the pre- and post-World War I eras led U.S. diplomats like Grew to cast the pre-war era in near-idyllic, carefree terms, when in fact the Department had developed several diplomatic security measures to counter acknowledged threats. -

PROCLAMATION 7026—SEPT. 19, 1997 111 STAT. 2981 National

PROCLAMATION 7026—SEPT. 19, 1997 111 STAT. 2981 Proclamation 7026 of September 19, 1997 National Farm Safety and Health Week, 1997 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation From the earliest days of our Nation, the men and women who work the land have held a special place in America's heart, history, and economy. Many of us are no more than a few generations removed from forebears whose determination and hard work on farms and fields helped to build our Nation and shape its values. While the portion of our population directly involved in agriculture has diminished over the years, those who live and work on America's farms and ranches continue to make extraordinary contributions to the quality of our na tional life and the strength of our economy. The life of a farmer or rancher has never been easy. The work is hard, physically challenging, and uniquely subject to the forces of nature; the chemicals and labor-saving machinery that have helped American farmers become so enormously productive have also brought with them new health hazards; and working with livestock can result in fre quent injury to agricultural workers and their families. Fortunately, there are measures we can take to reduce agriculture-relat ed injuries, illnesses, and deaths. Manufacturers continue to improve the safety features of farming equipment; protective clothing and safety gear can reduce the exposure of workers to the health threats posed by chemicals, noise, dust, and sun; training in first-aid procedures and ac cess to good health care can often mean the difference between life and death.