Chitlin Circuit Bob Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mow!,'Mum INN Nn

mow!,'mum INN nn %AUNE 20, 1981 $2.75 R1-047-8, a.cec-s_ Q.41.001, 414 i47,>0Z tet`44S;I:47q <r, 4.. SINGLES SLEEPERS ALBUMS COMMODORES.. -LADY (YOU BRING TUBES, -DON'T WANT TO WAIT ANY- POINTER SISTERS, "BLACK & ME UP)" (prod. by Carmichael - eMORE" (prod. by Foster) (writers: WHITE." Once again,thesisters group) (writers: King -Hudson - Tubes -Foster) .Pseudo/ rving multiple lead vocals combine witt- King)(Jobete/Commodores, Foster F-ees/Boone's Tunes, Richard Perry's extra -sensory sonc ASCAP) (3:54). Shimmering BMI) (3 50Fee Waybill and the selection and snappy production :c strings and a drying rhythm sec- ganc harness their craziness long create an LP that's several singles tionbackLionelRichie,Jr.'s enoughtocreate epic drama. deep for many formats. An instant vocal soul. From the upcoming An attrEcti.e piece for AOR-pop. favoriteforsummer'31. Plane' "In the Pocket" LP. Motown 1514. Capitol 5007. P-18 (E!A) (8.98). RONNIE MILSAI3, "(There's) NO GETTIN' SPLIT ENZ, "ONE STEP AHEAD" (prod. YOKO ONO, "SEASON OF GLASS." OVER ME"(prod.byMilsap- byTickle) \rvriter:Finn)(Enz. Released to radio on tape prior to Collins)(writers:Brasfield -Ald- BMI) (2 52. Thick keyboard tex- appearing on disc, Cno's extremel ridge) {Rick Hall, ASCAP) (3:15). turesbuttressNeilFinn'slight persona and specific references tc Milsap is in a pop groove with this tenor or tit's melodic track from her late husband John Lennon have 0irresistible uptempo ballad from the new "Vlaiata- LP. An air of alreadysparkedcontroversyanci hisforthcoming LP.Hissexy, mystery acids to the appeal for discussion that's bound to escaate confident vocal steals the show. -

Chicago Blues Festival Millennium Park + Citywide Programs June 7-9, 2019

36th Annual Chicago Blues Festival Millennium Park + Citywide Programs June 7-9, 2019 Open Invitation to Cross-Promote Blues during 36th Annual Chicago Blues Festival MISSION The Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE) is dedicated to enriching Chicago’s artistic vitality and cultural vibrancy. This includes fostering the development of Chicago’s non-profit arts sector, independent working artists and for-profit arts businesses; providing a framework to guide the City’s future cultural and economic growth, via the Chicago Cultural Plan; marketing the City’s cultural assets to a worldwide audience; and presenting high-quality, free and affordable cultural programs for residents and visitors. BACKGROUND The Chicago Blues Festival is the largest free blues festival in the world and remains the largest of Chicago's music festivals. During three days on seven stages, blues fans enjoy free live music by top-tier blues musicians, both old favorites and the up-and-coming in the “Blues Capital of the World.” Past performers include Bonnie Raitt, the late Ray Charles, the late B.B. King, the late Bo Diddley, Buddy Guy, the late Koko Taylor, Mavis Staples, Shemekia Copeland, Gary Clark Jr, Rhiannon Giddens, Willie Clayton and Bobby Rush. With a diverse line-up celebrating the Chicago Blues’ past, present and future, the Chicago Blues Festival features live music performances of over 60 local, national and international artists and groups celebrating the city’s rich Blues tradition while shining a spotlight on the genre’s contributions to soul, R&B, gospel, rock, hip-hop and more. AVAILABLE OPPORTUNITY In honor of the 36th Annual Chicago Blues Festival in 2019, DCASE will extend an open invitation to existing Blues venues and promoters to have their event marketed along with the 36th Annual Chicago Blues Festival. -

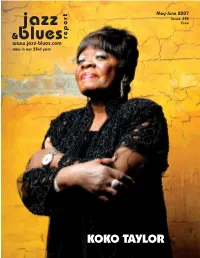

May-June 293-WEB

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

Extensions of Remarks E1699 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

October 16, 2012 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1699 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF BOY HONORING THE FAYETTE Mr. Speaker, Senator Arlen Specter will be SCOUT TROOP 21, ROCHESTER, MN SPIRITUAL AIRES remembered for the important bipartisan role he played. HON. TIMOTHY J. WALZ HON. BENNIE G. THOMPSON I urge my colleagues to join me in the mourning and remembering Senator Arlen OF MINNESOTA OF MISSISSIPPI Specter. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES f Tuesday, October 16, 2012 Tuesday, October 16, 2012 IN RECOGNITION OF THOMAS Mr. WALZ of Minnesota. Mr. Speaker, I ask Mr. THOMPSON of Mississippi. Mr. Speak- TIGHE the House to join me today in honoring the er, I rise today to honor a Gospel Singers’ 100th anniversary of Boy Scout Troop 21 in Group, The Fayette Spiritual Aires. Rochester, Minnesota. Troop 21 is one of the In 1975, God gave Jimmy Jackson a vision HON. FRANK PALLONE, JR. oldest and hardest working Boy Scout troops to organize a gospel quartet group, which he OF NEW JERSEY in Minnesota. named ‘‘The Fayette Spiritual Aires’’. Through- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Over the years, thousands of young men out the years, this group has touched many Tuesday, October 16, 2012 lives and led many to Christ through its sing- have passed through their program, learning Mr. PALLONE. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to valuable leadership and life skills while also ing ministry. The Fayette Spiritual Aires has been congratulate Mr. Thomas Tighe as he is rec- enjoying outdoor activities and performing ognized by the Kiddie Keep Well Camp on the service projects. -

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2010 By

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2010 By: Senator(s) Horhn, Burton, Butler, To: Rules Dearing, Fillingane, Frazier, Jackson (11th), Jackson (32nd), McDaniel, Simmons SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 642 1 A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION CELEBRATING AND COMMENDING THE CAREER 2 OF LEGENDARY GOSPEL MUSIC STARS THE JACKSON SOUTHERNAIRES. 3 WHEREAS, The Jackson Southernaires, one of America's most 4 outstanding gospel recording groups, was formed by Frank Crisler 5 in 1940 in Jackson, Mississippi, and are currently celebrating 6 their 70-year Anniversary; and 7 WHEREAS, The Jackson Southernaires were the first Gospel 8 group in the State of Mississippi to use the guitar, base, drum 9 and keyboard in their stage performances. Over a 70-year span, 10 The Jackson Southernaires have shared the stage with more than 15 11 members. In 1965, it was Frank Williams who introduced Huey 12 Williams to the music of The Jackson Southernaires; Huey was 13 singing with the Southern Gospel Singers during that time. It was 14 in the late 1960s, after Huey joined The Jackson Southernaires, 15 that their music caught the attention of Duke/Peacock Records. In 16 1968 the group released the single Too Late, which became one of 17 Duke/Peacock Records' largest selling albums; and 18 WHEREAS, in 1972, on the ABC/Dunhill Label, the album Look 19 Around was released and in 1974, Save My Child was released. The 20 albums Look Around and Save My Child charted nationally and 21 brought the group worldwide acclaim. In 1975, Malaco Records 22 signed The Jackson Southernaires as the first Gospel group for 23 this blues and R&B record company. -

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2018 By

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2018 By: Representative Straughter To: Rules HOUSE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 88 1 A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION MOURNING THE LOSS AND COMMEMORATING 2 THE LIFE AND STELLAR MUSIC CAREER OF MISSISSIPPI BLUES AND SOUL 3 LEGEND DENISE LASALLE AND EXPRESSING DEEPEST SYMPATHY TO HER 4 FAMILY AND FRIENDS UPON HER PASSING. 5 WHEREAS, it is written in Ecclesiastes 3:1, "To everything 6 there is a season, and a time for every purpose under the Heaven," 7 and as such, the immaculate author and finisher of our soul's 8 destiny summoned the mortal presence of dearly beloved Mississippi 9 songbird, renowned Mississippi R&B singer, songwriter and record 10 producer, the incomparable Mrs. Denise LaSalle, as she has made 11 life's final transition from earthly travailing to heavenly 12 reward, rendering great sorrow and loss to her family, friends and 13 fan base; and 14 WHEREAS, born Ora Denise Allen on July 16, 1934, in the 15 hamlet of Sidon, Leflore County, Mississippi, situated in the 16 heart of the Mississippi Delta, the seventh of eight children to 17 Mr. Nathaniel Allen, Sr., and Mrs. Nancy Cooper Allen; the State 18 of Mississippi lost a wonderful friend and icon with the passing 19 of Mrs. LaSalle, hailed by her fans as the "Queen of the Blues," H. C. R. No. 88 *HR31/R2150* ~ OFFICIAL ~ N1/2 18/HR31/R2150 PAGE 1 (DJ\JAB) 20 on January 8, 2018, and there is now a hush in our hearts as we 21 come together to pay our respects to the memory of one who has 22 been called to join that innumerable heavenly caravan as -

Wavelength (June 1983)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 6-1983 Wavelength (June 1983) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (June 1983) 32 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/32 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEVELOPING THE NEW LEADERSHIP IN NEW ORLEANS MUSIC A Symposium on New Orlea Music Business Sponsored by the University of New Orleans Music Department and the Division of Continuing Education and wavelength Magazine. Moderator John Berthelot, UNO Continuing Education Coordinator/Instructor in the non-credit music business program. PROGRAM SCHEDULE How To Get A Job In A New Orleans Music Club 2 p.m.-panel discussion on the New Orleans club scene. Panelists include: Sonny Schneidau, Talent Manager. Tipitina's, John Parsons, owner and booking manager, Maple Leaf Bar. personal manager of • James Booker. one of the prcx:lucers of the new recording by James Booker. Classified. Jason Patterson. music manager of the Snug Harbor. associate prcx:lucer/consultant for the Faubourg Jazz Club, prcx:lucer for the first public showing of One Mo· Time, active with ABBA. foundation and concerts in the Park. Toulouse Theatre and legal proceedings to allow street music in the French Quarter. Steve Monistere, independent booking and co-owner of First Take Studio. -

A Proclamation by Governor Ronnie Musgrove

A Proclamation By Governor Ronnie Musgrove WHEREAS, Pat Brown was born in Meridian, Mississippi on the 14th day of September; and WHEREAS, part of her musical beginnings, Pat Brown attended grade school and participated in, and won numerous talent shows—she later attended Harris Jr. College, where she joined a group called The Dynamics which later became The Commodores; and WHEREAS, after Jr. College, she attended Mississippi Valley State University where she continued to perform with numerous local and professional groups; and WHEREAS, after college, Pat Brown moved to Jackson, Mississippi to pursue her music career and has opened shows for and performed with many well known artists, including: B.B. King, Percy Sledge, Tyrone Davis, Bobby Rush, Al Green, Johnny Taylor, Willie Clayton; and WHEREAS, Pat Brown performs mainly in the south, but also in Detroit, Chicago, Washington, D.C., New York City, St. Louis, San Francisco, Long Beach, Milwaukee, Miami, Helsinki Finland and Amsterdam Holland and continues to perform for the entertainment and enjoyment of her fans: NOW, THEREFORE, I, Ronnie Musgrove, Governor of the State of Mississippi, hereby proclaim Pat Brown as a 2002 honoree of the Jackson Music Awards Mississippi Rhythm and Blues Diva and commend you for your talents and accomplishments in the music industry. IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the Great Seal of the State of Mississippi to be affixed. DONE in the City of Jackson, July 15, 2001, in the two hundred and twenty- sixth year of the United States of America. RONNIE MUSGROVE GOVERNOR. -

Twin Cities Funk & Soul

SEPTEMBER 25, 2012 I VOLUME 1 I ISSUE 1 DEDICATED TO UNCOVERING MUSIC HISTORY WILLIE & THE PROPHETS BAND OF KUXL JACKIE BUMBLEBEES OF PEACE THIEVES RADIO HARRIS 99 SECRET STASH ISSUE 1: TWIN CITIES FUNK & ANDSOUL MUCH SEPTEMBER MORE 25, 2012 The Philadelphia Story (AKA Valdons) mid 70s courtesy Minnesota Historical Society. Photo by Charles Chamblis. Left to right: Maurice Young, Clifton Curtis, Monroe Wright, Bill Clark Maurice McKinnies circa 1972 courtesy Minnesota Historical Society. Photo by Charles Dance contest at The Taste Show Lounge, Minneapolis late 70s courtesy Minnesota Historical Chamblis. Society. Photo by Charles Chamblis. 02 SECRET STASH VOLUME 1 - ISSUE 1: TWIN CITIES FUNK & SOUL SEPTEMBER 25, 2012 INTRODUCTION It was three years ago that we launched Secret Stash Records. About a year and a half lat- er, we started working on what would eventually become our biggest release, Twin Cities Funk & Soul: Lost R&B Grooves From Minneapolis/St. Paul 1964-1979. What follows is our attempt to share with you some of the amazing stories, history, and photos that have been so gracious- ly shared with us during the course of producing a compilation of soulful tunes from our hometown. ..... R&B, soul, and funk music in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota went through dra- matic changes during the 1960s and 1970s. Predating these changes, a vibrant jazz scene beginning in the 1920s laid the groundwork with several players being instrumental in helping teach young local R&B mu- sicians how to play. However, many of the early R&B pioneers, including Mojo Buford, Maurice McKin- nies, and Willie Walker, came to Minnesota from other states and brought the music with them. -

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2008 By

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2008 By: Representatives Coleman (65th), Bailey, To: Rules Broomfield, Calhoun, Campbell (72nd), Clark, Clarke, Coleman (29th), Espy, Evans (70th), Evans (91st), Gardner, Harrison, Holloway, Huddleston (30th), Middleton, Robinson, Scott, Smith (27th), Straughter, Thomas, Watson, Wooten, Brown HOUSE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 102 1 A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION COMMENDING AND CONGRATULATING MALACO 2 RECORDS ON RECEIVING A MARKER ON THE MISSISSIPPI BLUES TRAIL. 3 WHEREAS, Malaco Records, which is based in Jackson, 4 Mississippi, was honored on Tuesday, April 8, 2008, with a marker 5 on the Mississippi Blues Trail; and 6 WHEREAS, The Mississippi Blues Trail was created by the 7 Mississippi Blues Commission under the leadership of Governor 8 Haley Barbour and is designed to preserve the state's musical 9 heritage through historical markers and interpretive sites; and 10 WHEREAS, the roots of Malaco Records originated with 11 Cofounder Tommy Couch, Sr., who began booking R&B bands at the 12 University of Mississippi as Social Chairman of Pi Kappa Alpha 13 Fraternity; and 14 WHEREAS, after Mr. Couch graduated from college, he came to 15 Jackson to work as a pharmacist and formed a booking agency called 16 Malaco Productions with his brother-in-law, Mitchell Malouf; and 17 WHEREAS, in 1966, Malaco moved into recording and Couch's 18 fraternity brother, Gerald "Wolf" Stephenson, joined as a partner, 19 and in Malaco's initial years, it focused on leasing masters to 20 labels such as I Do Not Play No Rock 'N Roll by down-home 21 bluesman, Mississippi Fred McDowell; and 22 WHEREAS, Malaco found its niche in the early 1980s when it 23 signed Texan Z.Z. -

Luther Ingram

THE PITIFULS Hold My Heart To The Fire LocoBop L2I-012 Malaco Records’ house band in Jackson, MS was one of the best tight knit rhythm sections that southern studios were noted for in the 1960s and ‘70s. James Stroud (drums), Carson Whitsett (keyboards), Dino Zimmerman (guitar), and Don Barrett (bass) shaped hits by ZZ Hill, Dorothy Moore, Paul Simon, Paul Davis, Little Milton, Bobby Blue Bland, Johnnie Taylor, and Eddie Floyd. In the early 1980s, Stroud seized an opportunity to work with some of Nashville’s biggest names. Barrett, Zimmerman, and Whitsett, coincidently but individually, made Nashville their home as well. No longer a unit, they independently recorded with KT Oslin, Eddie Rabbitt, Janis Ian, Kathy Mattea, BB King, Eric Clapton, Suzy Bogguss, John Mayall, and Waylon Jennings. Whitsett also collaborated with Dan Penn, Tony Joe White, and others writing hits for Solomon Burke, Lorrie Morgan, John Anderson, Joe Cocker, and Conway Twitty. THE NEXT FOOL I FORGOT TO BE YOUR LOVER In 1996, Whitsett, Zimmerman, and Barrett reunited for a CLEAN SLATE one-off project with drummer Jimmy Hyde of Eddie SMOKE FILLED ROOM Rabbitt’s band and keyboardist Gene Sisk (Sawyer Brown, LOVE AT WORK The Judds, Earl Scruggs). Dubbing themselves The THE PITIFULS Pitifuls, they recorded this album in Memphis with Grammy- HOLD MY HEART TO THE FIRE award-winning engineer Danny Jones. THEY SAY BACKSLIDIN' Don Barrett sings lead on the majority of tracks, alternating I'M GONNA LOVE YOU OUT OF HIS LIFE with the grittier Jimmy Hyde. Except for Barrett's I'm Gonna Love You Right Out Of His Life and the Soul classic I Forgot To Be Your Lover, all songs were penned by Carson Whitsett, some in tandem with Dan Penn, Larry Byrom, Gary Nicholson, and others. -

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017 Researched, compiled, and calculated by Lance Mangham Contents • Sources • The Top 100 of All-Time • The Top 100 of Each Year (2017-1956) • The Top 50 of 1955 • The Top 40 of 1954 • The Top 20 of Each Year (1953-1930) • The Top 10 of Each Year (1929-1900) SOURCES FOR YEARLY RANKINGS iHeart Radio Top 50 2018 AT 40 (Vince revision) 1989-1970 Billboard AC 2018 Record World/Music Vendor Billboard Adult Pop Songs 2018 (Barry Kowal) 1981-1955 AT 40 (Barry Kowal) 2018-2009 WABC 1981-1961 Hits 1 2018-2017 Randy Price (Billboard/Cashbox) 1979-1970 Billboard Pop Songs 2018-2008 Ranking the 70s 1979-1970 Billboard Radio Songs 2018-2006 Record World 1979-1970 Mediabase Hot AC 2018-2006 Billboard Top 40 (Barry Kowal) 1969-1955 Mediabase AC 2018-2006 Ranking the 60s 1969-1960 Pop Radio Top 20 HAC 2018-2005 Great American Songbook 1969-1968, Mediabase Top 40 2018-2000 1961-1940 American Top 40 2018-1998 The Elvis Era 1963-1956 Rock On The Net 2018-1980 Gilbert & Theroux 1963-1956 Pop Radio Top 20 2018-1941 Hit Parade 1955-1954 Mediabase Powerplay 2017-2016 Billboard Disc Jockey 1953-1950, Apple Top Selling Songs 2017-2016 1948-1947 Mediabase Big Picture 2017-2015 Billboard Jukebox 1953-1949 Radio & Records (Barry Kowal) 2008-1974 Billboard Sales 1953-1946 TSort 2008-1900 Cashbox (Barry Kowal) 1953-1945 Radio & Records CHR/T40/Pop 2007-2001, Hit Parade (Barry Kowal) 1953-1935 1995-1974 Billboard Disc Jockey (BK) 1949, Radio & Records Hot AC 2005-1996 1946-1945 Radio & Records AC 2005-1996 Billboard Jukebox