Big Archives and Small Collections: Remarks on the Archival Mode in Contemporary Australian Art and Visual Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Von Sturmer Cv 2020

ANNA SCHWARTZ GALLERY DANIEL VON STURMER 1972 Born Auckland, New Zealand Lives and works in Melbourne EDUCATION 2002-03 Sandberg Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands 1997-99 RMIT University, Melbourne, Master of Arts by Research 1993-96 RMIT University, Melbourne, Bachelor of Arts, in Fine Art, Honours SELECTED SOLO SHOWS 2020 Daniel von Sturmer: Time in Material, M+P|Art, UK 2019 Painted Light, Geelong Performing Arts Centre CATARACT, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne Electric Light (facts/figures/anna schwartz gallery upstairs), Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne 2017 Electric Light (facts/figures), Bus Projects, Melbourne Daniel von Sturmer, Ten Cubed, Melbourne Luminous Figures, Starkwhite Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand 2016 Electric Light, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne 2014 These Constructs, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne Camera Ready Actions, Young Projects, Los Angeles Focus & Field, Young Projects, Los Angeles 2013 After Images, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne Daniel von Sturmer, Ten Cubed, Melbourne Daniel von Sturmer, as part of Ground Control series, Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio Production Stills, Courtenay Place Lightboxes, Wellington 2012 Small World, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne 2010 The Cinema Complex, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Sydney Video Works 2008-2009, Karsten Schubert Gallery, London 2009 Set Piece, Site Gallery, Sheffield, United Kingdom Painted Video, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Auckland Art Fair, Auckland 2008 Tableaux Plastique, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne 2007 The Object of Things, Australian Pavilion, -

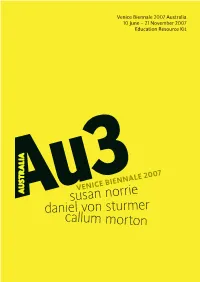

8082 AUS VB07 ENG Edu Kit FA.Indd

Venice Biennale 2007 Australia 10 June – 21 November 2007 Education Resource Kit Susan Norrie HAVOC 2007 Daniel von Sturmer The Object of Things 2007 Callum Morton Valhalla 2007 Contents Education resource kit outline Australians at the Venice Biennale Acknowledgements Why is the Venice Biennale important for Australian arts? Australia’s past participation in the Venice Biennale PART A The Venice Biennale and the Australian presentation Introduction Timeline: The Venice Biennale, a not so short history The Venice Biennale:La Biennale di Venezia Selected Resources Who what where when and why The Venice Biennale 2007 PART B Au3: 3 artists, 3 projects, 3 sites The exhibition Artists in profile National presentations Susan Norrie Collateral events Daniel von Sturmer Robert Storr, Director, Venice Biennale Callum Morton 2007 Map: Au3 Australian artists locations Curators statement: Thoughts on the at the Venice Biennale 2007 52nd International Art Exhibition Colour images Introducing the artist Au3: the Australian presentation 2007 Biography Foreword Representation Au3: 3 artists, 3 projects, 3 sites Collections Susan Norrie Quotes Daniel von Sturmer Commentary Callum Morton Years 9-12 Activities Other Participating Australian Artists Key words Rosemary Laing Shaun Gladwell Christian Capurro Curatorial Commentary: Au3 participating artists AU3 Venice Biennale 2007 Education Kit Australia Council for the Arts 3 Education Resource Kit outline This education resource kit highlights key artworks, ideas and themes of Au3: the 3 artists, their 3 projects which are presented for the first time at 3 different sites that make up the exhibition of Australian artists at the Venice Biennale 10 June to 21 November 2007. It aims to provide a entry point and context for using the Venice Biennale and the Au3 exhibition and artworks as a resource for Years 9-12 education audiences, studying Visual Arts within Australian High Schools. -

MCA, Tate and Qantas Announce Eight New Australian Artwork

[Sydney, 3 April 2018] Elizabeth Ann Macgregor OBE, Director of the Museum of Contemporary Left: Juan Davila, Love, 1988, Tate and Art Australia (MCA) and Dr Maria Balshaw CBE, Director of Tate, today announced the Museum of acquisition of eight new artworks in their International Joint Acquisition Program for Contemporary Art contemporary Australian art, supported by Qantas. Now in its third year, the partnership Australia, donated through the Australian between Tate, MCA and Qantas continues to enrich both museums’ holdings of Australian art, Government’s Cultural helping Australian artists reach global audiences. Gifts Program by the artist and with the Ranging from an early moment in the history of Australian contemporary art through to recent support of the Qantas Foundation, 2018 work, the depth and diversity of Australian art practice is represented in this third round of acquisitions. It includes works by artists who forged new ground in Australian contemporary art, Right: Maria paving the way for others, through to that of younger artists. Fernanda Cardoso, On the Origins or Art – Actual Size II Maratus The early works of Maria Fernanda Cardoso and Rosalie Gascoigne reveal how everyday Volans Abdomen, readymade materials can be transformed into extraordinary poetic assemblages and sculptures. 2016, Tate and the Museum of Juan Davila’s Love (1988) painting is a prescient commentary on the AIDS crisis as a global Contemporary Art phenomenon, whilst his also acquired massive Yawar Fiesta (1998) explores the impact of colonial Australia, purchased policies on indigenous peoples through satiric intertwining of contemporary politics and art jointly with funds provided by the historical references including European history painting, Latin American modernism, American Qantas Foundation pop and Aboriginal art. -

Michael Zavros CV LONG March 2016

Michael Zavros b.1974- Studies 1994 - 1996 Queensland College of Art, (GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY) Bachelor of Visual Arts, Double Major in Printmaking Solo Exhibitions 2016 Art Los Angeles Contemporary, Barker Hangar, Los Angeles, Solo exhibition presented by Starkwhite, Auckland 2015 Art Basel Hong Kong, Solo exhibition presented by Starkwhite, Auckland 2014 Bad Dad, Starkwhite, Auckland, New Zealand Melbourne Art Fair, Solo exhibition with Starkwhite, Melbourne 2013 A Private Collection: Artist’s Choice, Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane The Prince, Rockhampton Art Gallery, touring to Griffith University Art Gallery, Brisbane Charmer, Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2012 The Glass, Tweed River Art Gallery, NSW 2011 Michael Zavros, Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne 2010 The Savage, Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane 2009 Calling in the fox, GRANTPIRRIE, Sydney The Good Son; Michael Zavros, A survey of works on paper, Gold Coast City Art Gallery, Qld 2008 Trophy Hunter, Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane Melbourne Art Fair solo exhibition, Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne 2007 Heart of Glass, Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne ĒGOÏSTE, Wollongong City Gallery, Wollongong, NSW 2006 This Charming Man, 24HRArt Northern Territory Centre for Contemporary Art, Darwin 2005 The Look of Love, Mori Gallery, Sydney 2004 Clever Tricks, Grafton Regional Gallery, NSW Blue Blood, Schubert Contemporary, Gold Coast, Qld 2003 Everything I wanted, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane The Loved One, Mori Gallery, Sydney 2002 New money, Art Galleries Schubert, -

John Cruthers Presents

John Cruthers presents Australian art from the Re/production: 1980s and 1990s John Cruthers presents Re/production: Australian art from the 1980s and 1990s 29 August - 10 October 2020 -02 Narelle Jubelin Ian Burn Tim Johnson Tim Johnson & Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri Stephen Bush Geoff Lowe Judy Watson Eliza Campbell & Judith Lodwick Mark Titmarsh Luke Parker Elizabeth Newman Peter Tyndall Janet Burchill Anne Ferran Linda Marrinon Vivienne Shark LeWitt John Nixon Pat Larter Juan Davila Howard Arkley Susan Norrie Angela Brennan Savanhdary Vongpoothorn David Jolly -03 -04 Bananarama Republic Catriona Moore Map Recall two enmeshed postmodern and dissipated to the academies (the tendencies, both claiming zeitgeist status university, museum and gallery). Those glory as landmark exhibitions, and seen at the days of postmodern theoretical merch saw a time to be diametrically opposed: ‘Popism’ flourishing moment for little magazines laden (NGV 1982) and the 5th Biennale of Sydney with translations, unreadable experiments in (AGNSW 1984). The first was was Pop- ficto-criticism and cheaply-reproduced, B&W inflected: cool with stylistic quotation, irony folios. On the more established art circuit, and ambivalent speculations; the second hot a growing file of (largely white male) curators and hitched to neo-expressionist painting: shuttled between the arts organisations, wild and bitter, hegemonic whilst stressing major galleries and definitive survey shows. a regional genius loci. Some felt that neo- The street became a place for parties, not expressionism was an international boys’ marches. club of juggernaut blockbusters (eg the Italian Transavantgardia; Berlin’s wild ones etc). Yet both tendencies claimed the image as art’s ‘go-to’ investigative platform - a retreat from feral 1970s postmodern forays: ‘twigs and string’ open-form sculpture and conceptual directives; the grungier depths of punk; and the nappy and tampon work of cutting-edge feminism. -

Australia 53Rd International Art Exhibition LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 1

Australia 53rd International Art Exhibition LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 1 Commissioner’s Foreword When Shaun Gladwell returned from dealing with reflections that are personal, from a range of sources – government, western New South Wales in early 2009 cultural and environmental. corporate, individual and philanthropic – he had accumulated images that were to where none sits as mutually exclusive from Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro’s massive signal an extension to his work that was the other, conspicuous in its commitment. installation consumes the chapel of the included in the exhibition Think with the Ludoteca – its monumentalism and its I gratefully acknowledge the generous Senses – Feel with the Mind at the Venice stillness are like a memento mori as it assistance of our many public and private Biennale 2007. For Venice 2009 Shaun alludes to transience and impermanence. funding partners. I also warmly thank the is our artist for the Australian Pavilion. Vernon Ah Kee’s work represents themes artists, Tania Doropoulos (project manager Shaun’s involvement with the landscape of contemporary social and cultural politics, for Shaun Gladwell) and Felicity Fenner – and urban spaces – holds recognition of of Indigenous exclusion. But here the modern (curator for Once Removed) for their dedication the sense of place we Australians have in the representation of this exclusion is explored and commitment to presenting Australia’s history of our nation’s art. But his inquiring through long-standing emblematic symbols exhibitions at the Venice Biennale 2009. temperament and his keen interest in the that are representative of white Australian Doug Hall AM role of the culture of his own generation culture. -

Daniel Von Sturmer

ANNA SCHWARTZ GALLERY DANIEL VON STURMER SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 2015 Tara McDowell in Daniel von Sturmer: Focus & Field, Black Inc 2014 Jonathan Griffin, Daniel von Sturmer Focus & Field, in ArtReview, October, p146 George Melrod, Daniel von Sturmer: Focus & Field at Young Projects, Art LTD magazine http://www.artltdmag.com/index.php?subaction=showfull&id=1415403467&archive=&start_from=&ucat=32& Sharon Mizota, Daniel von Sturmer's video art: A delightful play on perception, Los Angeles Times, June 27 http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/culture/la-et-cm-daniel-von-sturmer-at-young-projects-20140623-story.html 2013 Dan Rule, Your Weekend: In the Galleries, The Age, June 1 Jennifer A. McMahon, Art and Ethics in a Material World: Kant's Pragmatist Legacy, Routledge, NY, 2013, (pp33-41) Max Delany et al, Melbourne Now, ex. cat., National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne 2012 Elizabeth Pedler, ‘Daniel von Sturmer’, ArtForum, November Rebecca McLean, ‘It’s a small world- Daniel von Sturmer in Melbourne & London’, artery, October Jennifer A. McMahon, ‘The Aesthetics of Perception: Form as a Sign of Intention’, Essays in Philosophy: Vol. 13: Iss. 2, Article 2 Cameron Buckner, ‘Ordering Our Attributions-of-Order: Commentary on McMahon’, Essays in Philosophy: Vol. 13: Iss. 2,Article 3 Sue Cramer, Less is More exhibition catalogue, Heide Museum of Art, Melbourne Sue Cramer, ‘Going Minimal’, The Melbourne Review, September, p38 John Hurrell, ‘Artists Responding to Lye’, http://eyecontactsite.com/2012/02/artists-responding-to-lye Daniel von Sturmer, -

2004–05 Annual Report

QUEENSLAND ART GALLERY QUEENSLAND ART 2004–05 ANNUAL REPORT QUEENSLAND ART GALLERY ANNUAL REPORT 2004–05 QUEENSLAND ART GALLERY REPORT OF THE QUEENSLAND ART GALLERY BOARD OF TRUSTEES FOR THE PERIOD 1 JULY 2004 TO 30 JUNE 2005 In pursuance of the provisions of the Queensland Art Gallery Act 1987 s 53, the Financial Administration and Audit Act 1977 s 46J, and the Financial Management Standard 1997 Part 6, the Queensland Art Gallery Board of Trustees forwards to the Minister for Education and the Arts its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2005. Wayne Goss Chair of Trustees PURPOSE OF REPORT This Annual Report documents the Gallery’s activities, initiatives and achievements during 2004–05, and shows how the Gallery met its objectives for the year and addressed government policy priorities. This comprehensive review demonstrates the diversity and significance of the Gallery’s activities, and the role the Gallery plays within the wider community. It also indicates direction for the coming year. The Gallery welcomes comments on the report and suggestions for improvement. We encourage you to complete and return the feedback form in the back of this report. CONTENTS GALLERY PROFILE 3/ VISION GALLERY PROFILE Increased quality of life for all Queenslanders through enhanced access, understanding and enjoyment of the 4/ visual arts and furtherance of Queensland’s reputation as a HIGHLIGHTS AND ACHIEVEMENTS culturally dynamic state. 7/ MISSION CHAIR’S OVERVIEW To be the focus for the visual arts in Queensland and a dynamic and accessible art museum of international 9/ standing. DIRECTOR’S OVERVIEW 10/ QUEENSLAND GALLERY OF MODERN ART 13/ COLLECTION GALLERY PROFILE Established in 1895, the Queensland Art Gallery opened in its present premises in June 1982. -

Report of the Queensland Art Gallery Board of Trustees

REPORT OF THE QUEENSLAND ART GALLERY BOARD OF TRUSTEES FOR THE PERIOD 1 JULY 2005 TO 30 JUNE 2006 PURPOSE OF REPORT In pursuance of the provisions of the Queensland Art Gallery This Annual Report documents the Gallery’s activities, Act 1987 s 53, the Financial Administration and Audit Act initiatives and achievements during 2005–06, and shows 1977 s 46J, and the Financial Management Standard 1997 how the Gallery met its objectives for the year and addressed Part 6, the Queensland Art Gallery Board of Trustees government policy priorities. This comprehensive review forwards to the Minister for Education and Minister for the demonstrates the diversity and significance of the Gallery’s Arts its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2006. activities, and the role the Gallery plays within the wider community. It also indicates direction for the coming year. The Gallery welcomes comments on the report and suggestions for improvement. Wayne Goss, Chair of Trustees We encourage you to complete and return the feedback form in the back of this report. CONTENTS Masami Teraoka 05/ GALLERY PROFILE Japan/United States b.1936 McDonald’s Hamburgers Invading Japan/Chochin-me 1982 06/ HIGHLIGHTS AND ACHIEVEMENTS 36 colour screenprint on Arches 88 paper, ed. 41/91, 54.3 x 36.5cm (comp.) 09/ CHAIR’S OVERVIEW Purchased 2005. The Queensland Government’s Gallery of Modern Art 11/ DIRECTOR’S OVERVIEW Acquisitions Fund COVER: 13/ QUEENSLAND ART GALLERY | GALLERY OF MODERN ART ‘TWO SITES, ONE VISION’ The Gallery of Modern Art under construction, 2006 17/ COLLECTION -

Two Rooms Susan Norrie Born 1953, Sydney Australia Lives and Works

Two Rooms Susan Norrie Born 1953, Sydney Australia Lives and works in Sydney, Australia National Gallery of i!toria Art S!"ool #19$%& National Gallery S!"ool, Sydney #19$1& Sele!ted solo e'"i(itions) *+1, *++,–1,: Susan Norrie, .ield /ork, 0an Potter 2useum, 2el(ourne 3niversity Rules of Play, Two Rooms, Au!kland *+1% Transit, Two Rooms, Au!kland *+11 Notes for Transit , Gior4io Persano Gallery, Torino *++9 Notes from 5avo!, Gior4io 1ersano Gallery, Torino S56T and 7nola, 8olle!tive Gallery, T"e 7nli4"tenments, 7din(ur4" International .estival, S!otland *++$ 5A 68, 5*nd eni!e Biennale, 1ala99o Giustinian, Italy *++% 3N:7RT6/, Gus .is"er Gallery, Au!kland *++3 eddy, Lawren!e /ilson Art Gallery, 3niversity of /estern Australia, 1ert" notes from under4round, 2useum of 8ontem;orary Art, Sydney *++* 3N:7RT6/, AGNS/ 8ontem;orary Art Pro<e!ts, Art Gallery of New Sout" /ales, Sydney 3N:7RT6/, Australian 8entre for 8ontem;orary Art, 2el(ourne, !ommissioned for t"e 2el(ourne .estival *++1 T"ermostat, =iasma, 2useum of 8ontem;orary Art, 5elsinki> Lord 2ori Gallery, Los An4eles & S6.A Gallery, 3niversity of 8anter(ury, 8"rist!"ur!" Sele!ted 4rou; e'"i(itions) *+1$–18 Tate 2odern :is;lay, London, s"owin4 Transit *+11 7very Brilliant 7ye: Australian Art of t"e 199+s, National Gallery of i!toria, 2el(ourne, s"owin4 InAuisition *+1% LBavenir #lookin4 forward&, 2ontreal Biennale Rules of Play, 8o!katoo Island *+13 Amon4 t"e 2a!"ines, :unedin Pu(li! Art Gallery Ca Natuurli<k – "ow art saves t"e world, Sti!"tin4 Niet Normal and Gemeentesmuseum :en 5aa4 *+1* -

Fine Arts 2014–15

2014–15 Fine Arts 2014–15 Acknowledgements All works © the artists and architect Antonella Salvatore and Inge Lyse Hansen, John Cabot University, Rome Editor: Marco Palmieri Translations: Beatrice Gelosia Juliet Franks, The Ruskin School of Art, University Graphic design: Praline of Oxford, Oxford Printed in Belgium by Graphius Sarah Linford, Accademia di Belle Arti di Roma, Rome Published in 2015 by the British School at Rome Anna d’Amelio Carbone, Fabrizio Del Signore, Adrienne Drake, 10 Carlton House Terrace Niccolò Fano, Hou Hanru, Manuela Pacella, Armando Porcari, London SW1Y 5AH Carolina Pozzi, Donatella Saroli, Marcello Smarrelli, Carmen Stolfi British School at Rome Via Gramsci 61, 00197 Rome Giulia Carletti, Francesca Gallo, Stella Rendina, Anne Stelzer Registered Charity 314176 Photography courtesy of the artists and architects, except: Roberto Apa (pages 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 16–19, 22–37, 40–5, www.bsr.ac.uk 48–51), Grant Hancock (pages 20, 21) and Don Hildred (pages 46, 47) ISSN 1475-8733 ISBN 978-0-904152-73-9 The projects realised by Angela Brennan, Gregory Hodge, Susan Norrie and Mona Ryder have been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its Arts funding and advisory body. The Incorporated Edwin Austin The Derek Hill Foundation Abbey Memorial Scholarships Nicholas Berwin Charitable Trust Contents 4 Preface: Christopher Smith 6 Introduction: Marco Palmieri Exhibitors 16 Georges Audet 18 Angela Brennan 20 Nic Brown 22 Adam Nathaniel Furman 24 Paul James Gomes 26 Rowena Harris 28 Gregory Hodge 30 Alexi Keywan 32 David McCue 34 Gina Medcalf 36 Nancy Milner 38 Susan Norrie 40 Catherine O’Donnell 42 Gill Ord 44 Florian Roithmayr 46 Mona Ryder 48 Daniel Sinsel 50 Emily Speed 52 Biographies 63 BSR Faculty of the Fine Arts and Staff Preface / Prefazione The community of artists at the BSR is not only the La comunità di artisti residenti alla BSR non è costituita community of any given year, but stretches back across soltanto dal gruppo di ogni singolo anno, ma si a century. -

Queensland Art Gallery Annual Report

2006–07 QUEENSLAND ART GALLERY ANNUAL REPORT REPORT OF THE QUEENSLAND ART GALLERY BOARD OF TRUSTEES FOR THE PERIOD 1 JULY 2006 TO 30 JUNE 2007 PURPOSE OF REPORT In pursuance of the provisions of the Queensland Art This Annual Report documents the Gallery's activities, Gallery Act 1987 s 53, the Financial Administration and initiatives and achievements during 2006 –07, and Audit Act 1977 s 46J, and the Financial Management shows how the Gallery met its objectives for the year and Standard 1997 Part 6, the Queensland Art Gallery Board addressed government policy priorities. This comprehensive of Trustees forwards to the Minister for Education and review demonstrates the diversity and significance of the Training and Minister for the Arts its Annual Report for Gallery's activities, and the role the Gallery plays within the year ended 30 June 2007. the wider community. It also indicates direction for the coming year. The Gallery welcomes comments on the report and suggestions for improvement. We encourage you to complete and return the feedback form in the back of this report. Wayne Goss, Chair of Trustees CONTENTS COVER AND GATEFOLD CAPTIONS. 05/ GALLERY PROFILE Text 06/ Highlights AND ACHIEVEMents 09/ ChAIR'S OVERVIEW 11/ ACTING DIRECtor'S OVERVIEW 13/ ColleCTION 23/ EXHIBITIONS AND AudienCes 29/ FOCUS: 'THE 5TH ASIa–PACIFIC TRIENNIAL OF ConteMPORARY Art' 37/ INITIATIVes AND SERVICes 45/ PROGRAMS OF AssistANCE 47/ AppendiXes 48/ ORGANISATIONAL Purpose AND ResponsiBilities 49/ PROGRAM STRUCTURE 2006–07 50/ STRAtegiC DIRECTION 51/ Meeting