Digest of the 1951 Census Report for Bombay, Saurashtra and Kutch CORRIGENDUM• Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kutch Basin Forms the North-Western Part of the Western Continental

Basin Introduction :. Kutch basin forms the north-western part of the western continental margin of India and is situated at the southern edge of the Indus shelf at right angles to the southern Indus fossil rift (Zaigham and Mallick, 2000). It is bounded by the Nagar- Parkar fault in the North, Radhanpur-Barmer arch in the east and North Kathiawar fault towards the south. The basin extents between Latitude 22° 30' and 24° 30' N and Longitudes 68° and 72° E covering entire Kutch district and western part of Banaskantha (Santalpur Taluka) districts of Gujarat state. It is an east-west oriented pericratonic embayment opening and deepening towards the sea in the west towards the Arabian Sea. The total area of the basin is about 71,000 sq. km of which onland area is 43,000 sq.km and offshore area is 28,000 sq.km. upto 200 bathymetry. The basin is filled up with 1550 to 2500m of Mesozoic sediments and 550m of Tertiary sediments in onland region and upto 4500m of Tertiary sediments in offshore region (Well GKH-1). The sediment fill thickens from less than 500m in the north to over 4500m in the south and from 200m in the east to over 14,000m in the deep sea region towards western part of the basin indicating a palaeo-slope in the south-west. The western continental shelf of India, with average shelf break at about 200 m depth, is about 300 km wide off Mumbai coast and gradually narrows down to 160 km off Kutch in the north. -

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

SELF FINANCE COLLEGE LIST Dt

SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY - SELF FINANCE COLLEGE LIST Dt. 29-9-2016 NO. COLLEGE NAME CITY TALUKA DISTRICT Principal Mobile No. Address E- MAIL 1 Shri Saradar Patel & Swami AMRAPUR KUKAVAV AMRELI Ph. (02796) 238888 At. Post Amrapur ddbkngcollege@yahoo Vivekand Lok Kalyan Trust Mo.279329503, Tal- kunkavavDist;- Amreli 9979477751 .com Sanchalit, Matushri D. Bhimani & Kashiben Gevariya Commerce, B.B.A., B.C.A. College 2 Shri Vivek Vidhya Vikas Amreli AMRELI AMRELI AMRELI C - 225639 R – Omnagar - 3, Behind Trust Sanchalit, Shree 231955, 9426243250 Mohannagar,Behind G.I.D.C., Commerce & B.B.A. College AMRELI - 365 601 3 Shri Amreli Jilla Leauva Patel AMRELI AMRELI AMRELI C. 02792-232321 to 26 Smt. Shantaben Gajera [email protected] Charitable Trust Sanchit, M. 94271 73206 Shaikshanik Sankul, Chhakargadh Road, Near Shri K. P. Dholakiya Info. Mahila Bypass, AMRELI College 4 Srei Amreli Jilla Leuva Patel AMRELI AMRELI AMRELI C. (02792) 232321 Smt. Santaben Gajera [email protected] Charitable Trust Sanchalit, Shri M. 99987 12526 Shaikshnik Sankul, Near Bypass Chakkargadh Road, Kabariya Arts & Vaghasiya AMRELI Commerce & Bhagat Science Mahila College 5 Shri Amreli Jilla Leauva Patel AMRELI AMRELI AMRELI C 232327 Smt. Shantaben Gajera Charitable Trust Sanchalit, Smt. Shaikshanik Sankul, Chakkargadh Road, Near M. J. Gajera Mahila B.Ed. Bypass,AMRELI College 6 Shri L. D. Dhanani Arts College AMRELI AMRELI AMRELI Mo.9374212011 Bh. B.K. Tank Dela, ld_artscollegeamreli@ Chakkargadh Road, AMRELI , yahoo.com 7 Shri Amreli Jill Leuva Patel Trust AMRELI AMRELI AMRELI Ph. (02792) 232324 Chhakar Gadh Road, Sanchalit, B. B. A. Mahila 9426632328 AMRELI College 8 Shri Swami Narayan Gurukul AMRELI AMRELI AMRELI Ph. -

J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J

j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j DhananJa}arao Gadglillbrary j 111111111111 InlllIlll Illilllill DIIIIH GIPE-PUNE-IOI540 j j f '----- - j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j SELECTIONS FI10M THE RECORDS OF THE BOMBAY GOVERNMENT. ~ (IN Two PARTS.)-NEW SERIES. Y;-"'~Vtlf _____ PART I. REPORT~ ON THE RESOURCES, &0., OF THE • DISTRICTS OF NADIAD, ~IT~R, w)NDE~, JUJAPUR, DHOLKA. DHANDHUKA, AND GOGH( THE TAPPA OF NAPAD, AND THE . KASBA OF RANPUR, IN GUJARAT: . / ACCOMPANIED EY ERIEF NO~ RELATIVE TO THE OONDITION OF THAT PROVINCE PREVIOUS TO THE OLOSE OF THE LAST CENTURY. A • of': .. ~_. ~,..._~ __ .... __ ~ ____ ~ WI';['H MEMOIRS ON 'THE DISTRICT~_ O~ JHALAVAD: KaTHIAWAR PROPER, MACHU KAN"'tHA, NAVANAGAR • . GOHELVAD, PORBANDAR, SORATH, AND HALAR, IN KATEIAW AP :" _)._1 ACCOMPANIED BY MISCELLANEOU~ INFORMATION ,CONNECTED WJTH THAT PBOYINCE ~ By (THE LATE) COLONEL ALEXANDER WALKER PART. II., REPORTS OF THE , " MEASURES; tJOMMENCING WITH 'ra.~ YEA:& 180;), AD6PTED) IN CONCERT WITH THE GOVERNMENT, BY. -THE LA~E COLONEL- ALEXANDER WALKER; ANP SuBSEQUENTLY BYMlt r.-V: WILLOUGHBY, POLITICAL AGENT IN KATHIAWAR, AND BY HIS SUCCESSORS, FOR THE SUPPRESSION OF FEMALE INFANTI CIDE1N THAT PROVINCE . •C01'lPILED &r EDITED BY R. HUGHES TROnS. ASSISTANT SEORETARY, POLITICAL DEPARTMEl!T , ~.O'mbaJl! REPRINTED AT THE GOVER;NMENT CENTRAL PRESS. -1~93. ~B3TRACT -OF CONTENTS. PARTt fAG.e. Qt1lARA~-Reporta on the ResourCt>s, &c., uf.the j;lhtrll:ts of Nll.duld, Mdtar, Mahudha, BIJapur, Dholka, Dhl.llldhuka and GogN:, the T'lppa of Napa.r, and thE' Kasba of Ranpur In the Plovlnce of GujarMf. -

General Report on the Census, Economic Trends and Projections, Part I-A(Iii), Vol-V

PRG. 4.III(N) (D) 75 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PART I-A (iii) GENERAL REPORT ON THE CENSUS ECONOMIC TRENDS AND PROJECTIONS R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PRICE Rs. 16.00 P. or 37 Sh. 4 d. or $ U.S. 5.76 Z :!'. ~ 0 ell • I i ell " I I"I I iii """ 0 " o "... CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V -Gujarat is being published in~ the following parts: I-A(i) General Report I-A(ii) " I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey I-C Subsidiary Tables II-A General Population Tables II-B (1) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) II-B (2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) II-C Cultural and Migration Tables III Household Economic Tables (Tables n-X to B-XVII) IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Selected Crafts of Gujarat VII-B Fairs and Festivals VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration I Not for Sale VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation J IX Atlas Volume X-A Special Report on Cities X-B Special Tables on Cities and Block Directory X-C Special' Migrant Tables for Ahmedabad City STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS 1 7 District Census Handbooks in English 17 District Census Handbooks in Gujarati PRIN1'ED BY JIVANJI D. -

Bombay Act No. Lxxviii of 1958

GOVERNMENT OF GUJARAT LEGISLATIVE PARLIAMENTARY AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT BOMBAY ACT NO. LXXVIII OF 1958 THE JUDICIAL OFFICER PROTECTION(EXTENSION TO HYDERABAD AND SAURASHTRA AREA OF BOMBAY STATE) ACT,1958. (As modified upto the 31st October, 2006) THE JUDICIAL OFFICERS’ PROTECTION (EXTENSION TO HYDERABAD AND SAURASHTRA AREAS OF BOMBAY STATE) ACT, 1958. .................................... CONTENTS PREAMBLE PAGE NO. SECTIONS. 1. Short title. 2. Extension of Act XVIII of 1850 to Hyderabad and Saurashtra areas of Bombay State. 3. Repeal and Saving. BOMBAY ACT NO. LXXVIII OF 19581 [THE JUDICIAL OFFICERS PROTECTIONS (EXTENSIONS TO HYDERABAD AND SAURASHTRA AREAS OF BOMBAY STATE) ACT, 1958.] [7th October , 1958] An Act to extend the Judicial Officers’ Protection Act, 1850, to the Hyderabad and Saurashtra areas of the State of Bombay. XVIII of WHEREAS the Judicial Officers’ Protection Act, 1850, is in force in the whole of 1850. the State of Bombay except the territories which immediately before the 1st November 1956 were comprised in Part B States : AND WHEREAS in the Hyderabad area of the State the Protection of Nazims and Hyd. IV of Servants Act is in force and in the Saurashtra area the Judicial Officers’ Protection Act, 1314. Fasli XVIII of 1850 as adapted and applied by the State of Saurashtra (Application of Central and 1850. Bombay Acts) Ordinance, 1948 is in force ; Sau. Ord. XXV of 1948. AND WHEREAS it is expedient that the Judicial Officers’ Protection Act, 1850 as in force in the rest of the State of Bombay be extended to and brought into force also in the Hyderabad and Saurashtra areas thereof ; and in consequence the corresponding laws aforesaid be repealed ; It is hereby enacted in the Ninth Year of the Republic of India as follows :- 1. -

PLP 2016-17 Gir Somnath District EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A

PLP 2016-17 Gir Somnath District EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A. Introduction Gir Somnath is primarily an agricultural district with Cotton, Groundnut and Sugarcane as the predominant crops. The other major crops cultivated are wheat, sesam, bajara, jowar . About 71 % of land holdings are with small and marginal farmers and the average size of the holdings is 2.0 ha. The Potential Linked Credit Plan (PLP) for 2016-17 has been prepared aligning with the revised RBI guidelines on Priority Sector Lending. It estimates credit flow of Rs.352906.94 lakh, of which, Crop Production sector has a major share of 38.64 % at ` 136386.27 lakh. Term loan under agriculture is assessed at ` 88288.91 lakh accounting for about 39.3 % of total agriculture. Under MSME, ` 26397.01 lakh has been assessed as potential forming 7.63% and balance at ` 101834.75 lakh has been estimated for other sectors like Exports, Education, Housing, . The activity-wise and block-wise assessment of potential is presented in Annexure I. The PLP projection for 2016-17 is higher by Rs. 103869.45 lakh when compared to the PLP for the year 2015-16 representing an increase of 42.9%. Further, the PLP projection is higher by ` 103867.47 lakh when compared to the ACP target for the year 2015-16. Suggested action Points in respect of major sectors and infrastructure/non-credit inputs are as under: B. Sector-wise comments on major sectors 1. Crop Production, Maintenance and Marketing There is need to adopt of advanced technologies for the restoration of soil health, increase mechanisation, and cultivation of suitable remunerative crops. -

KATHIAWAD POLITICAL ASSOCIATIO Dr

KATHIAWAD POLITICAL ASSOCIATIO Dr. Archana R. Bansod M. A., Ph.D., NET & SET (History), Assistant Professor & Director I/c (Centre for Studies & Research on Life & Works of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel (CERLIP) Vallabh Vidya Nagar, Anand, Gujarat. INTRODUCTION Entire region of Saurashtra was administrated by princely states before independence i.e. no single political power was controlling on entire region. Princely states were divided into so many divisions at the establishment of ‘Kathiawad Political Association’. Bhavnagar, Gondal, Morabi, Rajkot, Vakaner, Wadhwan and Jasdan states were of first or second division, and were immerged as developed states while states like Junagadj, Jamnagar, Dhangandhra, Porbandar and Limbdi were facing social disorder. There was no enthusiasm for change in this states which were of third of forth division states. In short, contradictory attitude of these stares played of decisive base for establishment of Kathiawad Political Association. Factors for originating and Establishment of Kathiawad Political Association: Establishment of ‘Kathiawad Political Association’ was just like a turning point in the history of Saurashtra of 26th century because it was a foundation stone of new era in political life of Saurashtra. It had totally covered political life of Saurashtra by its resolution and creative works by various conferences. Conference of Kathiawad Political Association were as under: VARIOUS CONFERENCES OF KATHIAWAD POLITICAL ASSOCIATION Sr. No. of Date Place President of President of No. conferences Association Conference 1 first 27 to 30 March Rajkot Vitthalbhai Z. Patel Liladhar Amrutlal 1921 Mehata 2 Special 8-9 July, 1922 Mumbai Faizi Badurddin Girijashankar Taiyabji Bhavanji Trevedi 3 Second 11-13 Wadhwan Abbas Varteji Taiyabji Mohanlal November. -

Sir Creek: the Origin and Development of the Dispute Between Pakistan and India

IPRI Journal 1 SIR CREEK: THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE DISPUTE BETWEEN PAKISTAN AND INDIA Dr Rashid Ahmad Khan∗ ir Creek is one of the eight long-standing bilateral disputes between Pakistan and India that the two countries are trying to resolve under S the ongoing composite dialogue process. It is a dispute over a 96 km (60 miles) long strip of water in the Rann of Kutch marshlands of the River Indus, along the border between the Sindh province of southern part of Pakistan and the state of Rajasthan in India. For the last about 40 years, the two countries have been trying to resolve this row through talks. Although, like other bilateral issues between Pakistan and India, the row over Sir Creek, too, awaits a final solution, this is the only area where the two countries have moved much closer to the resolution of the dispute. Following a meeting between the foreign ministers of Pakistan and India on the sidelines of 14th SAARC Summit in New Delhi, an Indian official announced that the two countries had agreed on a common map of Sir Creek, after the completion of joint survey agreed last year. “W e have one common map of the area, from which we will now work and try and see how far we can take this issue to a resolution, hopefully,” declared the Indian Foreign Secretary Shivshankar Menon after Foreign Minister of Pakistan, Mr. Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri, met his Indian counterpart, Mr. Pranab Mukherji in New Delhi on 2 April 2007.1 W hile discussing the prospects of the resolution of this issue in the light of past negotiations between the two countries, this paper aims to examine the implications of the resolution of this issue for the ongoing peace process between Pakistan and India. -

Bhavnagar Division

Tourist Places Bhavnagar Division Bhavnagar is the fifth largest city of Gujarat, after Ahmedabad, Surat, Vadodara and Rajkot; and the second largest city in the Saurashtra region. It is also known as the cultural capital of Saurashtra. Bhavnagar was founded in 1724 by Bhavsinhji Gohil. It was the capital of Bhavnagar State, which was a princely state before it was merged into the Indian Union in 1948. Home to socialism, reforms, and cultural legacy, Bhavnagar is considered a city of education and culture, and is known as the cultural capital of Saurashtra. Bhavnagar is one of the best places to shop for traditional jewelry and clothes. It is also famous for the handicrafts and their applique design. The places of attraction in and around Bhavnagar are: PORBANDAR Porbandar is a coastal city in Gujarat, perhaps best known for being the birthplace of Mahatma Gandhi and Sudama (friend of Lord Krishna). Gandhiji was born in Porbandar in 1869. The city is rich in cultural and historical heritage. There are many monuments and temple of great historical importance like the Kirti Mandir which is a memorial to Mahatma Gandhi. It is built next to the haveli where Mahatma Gandhi was born. The Kirti Mandir, Porbandar has a memorial of Mahatma Gandhi and contains a library with books on Gandhism, a spinning hall, a children's nursery and a lovely prayer hall. In the prayer hall of the Kirti Mandir prayers of all faith are regularly organized. Best buys : Textiles with bandhani work. Gharchola, a special kind of bandhani which is made in cotton, laharia Nearest Rail Head : Porbandar and chunari prints. -

History Sem-2

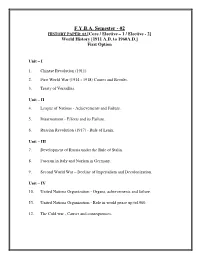

F.Y.B.A. Semester - 02 HISTORY PAPER: 03 [Core / Elective – 1 / Elective - 2] World History [1911 A.D. to 1960A.D.] First Option Unit – I 1. Chinese Revolution (1911) 2. First World War (1914 - 1918) Causes and Results. 3. Treaty of Versailles. Unit – II 4. League of Nations - Achievements and Failure. 5. Disarmament - Efforts and its Failure. 6. Russian Revolution (1917) - Rule of Lenin. Unit – III 7. Development of Russia under the Rule of Stalin. 8. Fascism in Italy and Nazism in Germany. 9. Second World War – Decline of Imperialism and Decolonization. Unit – IV 10. United Nations Organization - Organs, achievements and failure. 11. United Nations Organization - Role in world peace up to1960. 12. The Cold war - Causes and consequences. REFERENCE BOOKS: 1. Revil, J.C . : World History (Longmans Green & Co. London,1962) 2. Weech, W.N. : History of the World (Asia publishing House, Bombay,1964) 3. Vairanapillai, M.S. : A Concise World History (Madura Book House,Madurai) 4. Sharma, S.R. : A Brief Survey of HumanHistory 5. Hayes, Moon & Way Land : World History (Mac Millan, New York,1957) 6. Thoms, David : World History (O.U.P. London,1956) 7. Langsam, W.C. : The World Since 1919 (Mac Millan, New York,1968) 8. Ketelby C.D.M. : A History of Modern Times from 1789 (George G. Harrap& Co. London,1966) 9. SF{X, o VFW]lGS lJ`JGM .lTCF; 10. l+5F9L4 ZFD5|;FN o lJ`J .lTCF; slCgNL ;lDlT4 ,BGF{f 11. XDF"4 ZFWFS'Q6 o N]lGIFGL SCFGL EFU !vZ 12. lJnF,\SFZ4 ;tIS[T] o I]ZM5GL VFW]lGS .lTCF; s;Z:JTL ;NG4 D{;]ZL !)*Zf 13. -

Saurashtra Land Reforms Act, 1951

The Saurashtra Land Reforms Act, 1951 GOVERNMENT OF GUJARAT LEGISLATIVE AND PARLIAMENTARY AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT Saurashtra Act No. XXV of 1951 The Saurashtra Land Reforms Act, 1951 (As modified upto the 31st December, 2005) 1 of 33 The Saurashtra Land Reforms Act, 1951 1951 :Sau. Act XXV] THE SAURASHTRA LAND REFORMS ACT, 1951. -------------------- CONTENTS. PREAMBLE. SECTIONS. CHAPTER I. PRELIMINARY. 1. Short title, extent and commencement. 2. Definitions. 3. Act to over-ride other laws. CHAPTER II. LAND REVENUE AND CLASSIFICATION OF GIRASDARS. 4. All Girasdari land liable to payment of land revenue, 5. Classification of Girasdars. CHAPTER III. GIRASDARS AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP WITH TENANTS. 6. Persons when deemed to be tenants. 7. Restrictions on rent. 8. Cess, rate, hak, tax or service not leviable. 9. Penalty, refund and compensation. 10. Land revenue payable by Girasdar. 11. Suspension or remission of rent. 12. Termination of tenancy. 13. Relief against termination of tenancy for non-payment. 13A. Termination of tenancy not to take effect in certain cases. 13B. Assistance to Girasdar for recovery of rent. 14. Bar to eviction from dwelling-house. 15. Relief against eviction from dwelling-house in certain cases. 16. Dwelling-house of agricultural labourers. 17. Restoration of possession. 18. Act not to affect rights or privileges of tenant under any other law. CHAPTER IV. ALLOTMENT OF LAND TO GIRASDARS FOR PERSONAL CULTIVATION. 19. Application by Girasdars for allotment of land for personal cultivation. 20. Inquiry by Mamlatdar and order of allotment. 21. Allotment of land to Girasdars of A and B class. 2 of 33 The Saurashtra Land Reforms Act, 1951 SECTIONS.