Defining a Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hudson River School

Hudson River School 1796 1800 1801 1805 1810 Asher 1811 Brown 1815 1816 Durand 1820 Thomas 1820 1821 Cole 1823 1823 1825 John 1826 Frederick 1827 1827 1827 1830 Kensett 1830 Robert 1835 John S Sanford William Duncanson David 1840 Gifford Casilear Johnson Jasper 1845 1848 Francis Frederic Thomas 1850 Cropsey Edwin Moran Worthington Church Thomas 1855 Whittredge Hill 1860 Albert 1865 Bierstadt 1870 1872 1875 1872 1880 1880 1885 1886 1910 1890 1893 1908 1900 1900 1908 1908 1902 Compiled by Malcolm A Moore Ph.D. IM Rocky Cliff (1857) Reynolds House Museum of American Art The Beeches (1845) Metropolitan Museum of Art Asher Brown Durand (1796-1886) Kindred Spirits (1862) Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art The Fountain of Vaucluse (1841) Dallas Museum of Art View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm - the Oxbow. (1836) Metropolitan Museum of Art Thomas Cole (1801-48) Distant View of Niagara Falls (1836) Art Institute of Chicago Temple of Segesta with the Artist Sketching (1836) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston John William Casilear (1811-1893) John Frederick Kensett (1816-72) Lake George (1857) Metropolitan Museum of Art View of the Beach at Beverly, Massachusetts (1869) Santa Barbara Museum of Art David Johnson (1827-1908) Natural Bridge, Virginia (1860) Reynolda House Museum of American Art Lake George (1869) Metropolitan Museum of Art Worthington Whittredge (1820-1910) Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823-1900) Indian Encampment (1870-76) Terra Foundation for American Art Starrucca Viaduct, Pennsylvania (1865) Toledo Museum of Art Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823-1880) Robert S Duncanson (1821-1902) Whiteface Mountain from Lake Placid (1866) Smithsonian American Art Museum On the St. -

Asher Brown Durand Papers

Asher Brown Durand papers Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Asher Brown Durand papers AAA.duraashe Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Asher Brown Durand papers Identifier: AAA.duraashe Date: 1812-1883 Creator: Durand, Asher Brown, 1796-1886 Extent: 4 Reels (ca. 1000 items (on 4 microfilm reels)) Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Microfilmed 1956 by -

The Artist and the American Land

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1975 A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land Norman A. Geske Director at Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska- Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Geske, Norman A., "A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land" (1975). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 112. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/112 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME I is the book on which this exhibition is based: A Sense at Place The Artist and The American Land By Alan Gussow Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 79-154250 COVER: GUSSOW (DETAIL) "LOOSESTRIFE AND WINEBERRIES", 1965 Courtesy Washburn Galleries, Inc. New York a s~ns~ 0 ac~ THE ARTIST AND THE AMERICAN LAND VOLUME II [1 Lenders - Joslyn Art Museum ALLEN MEMORIAL ART MUSEUM, OBERLIN COLLEGE, Oberlin, Ohio MUNSON-WILLIAMS-PROCTOR INSTITUTE, Utica, New York AMERICAN REPUBLIC INSURANCE COMPANY, Des Moines, Iowa MUSEUM OF ART, THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, University Park AMON CARTER MUSEUM, Fort Worth MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON MR. TOM BARTEK, Omaha NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington, D.C. MR. THOMAS HART BENTON, Kansas City, Missouri NEBRASKA ART ASSOCIATION, Lincoln MR. AND MRS. EDMUND c. -

A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Hart Autograph Collection, 1731-1918, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Hart Autograph Collection, 1731-1918, in the Archives of American Art Jayna M. Josefson Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art 2014 February 20 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Charles Henry Hart autograph collection, 1731-1918............................... 4 Series 2: Unprocessed Addition, 1826-1892 and undated..................................... 18 Charles Henry Hart autograph collection AAA.hartchar Collection -

America Past

A Teacher’s Guide to America Past Sixteen 15-minute programs on the social history of the United States for high school students Guide writer: Jim Fleet Series consultant: John Patrick 01987 KRMA-W, Denver, Colorado and Agency for Instructional Technology Bloomington, Indiana AH rights reserved. This guide, or any part of it, may not be reproduced without written permission. Review questions in this guide maybe reproduced and distributed free to students. All inquiries should be addressed to: Agency for Instructional Technology Box A Bloomington, Indiana 47402 Table Of Contents Introduction To The AmericaPastSeries . 4 About Jim Fleet . ...!.... 5 America Past: An Overview . 5 How To Use This Guide . 5 Sources On People And Places In America Past . 5 Programs I. New Spain . 6 2. New France . 9 3. The Southern Colonies . 11 4. New England Colonies . 13 5. Canals and Steamboats . 16 6. Roads and Railroads, . .19 7. The Artist’s View . ... ..,.. 22 8. The Writer’s View . ...25 9. The Abolitionists . ...27 10. The Role of Women . ...29 ll. Utopias . ...31 12. Religion . ...33 13. Social Life . ...35 14. Moving West . ...38 15. The Industrial North . ...41 16. The Antebellum South . ...43 Textbook Correlation Chart . ...46 AnswerKey . ...48 Introduction To The America Past Series Over the past thirty years, it has been my experience that most textbooks and visual aids do an adequate job of cover- ing the political and economic aspects of American history UntiI recently however, scant attention has been given to social history. America Past was created to fill that gap. Some programs, such as those on religion and utopias, elaborate upon topics that may receive only a paragraph or two in many texts. -

Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected]

1 Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected] Education Feb. 1973 PhD., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Thesis: "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes," (Published by Garland, 1977). Adviser: Professor Robert Goldwater. Jan. 1968 M.A., Hunter College, City University of New York. Thesis: "The Portraits of Thomas Eakins: The Elements of Interpretation." Adviser: Professor Leo Steinberg. June 1957 B.A., Stanford University. Major: Modern European Literature Professional Positions 9/1978 – 7/2014 Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University: Acting Chair, Spring 2009; Spring 2012. Chair, 1995-97; Professor 1988-2014; Associate Professor, 1978-88 [retired 2014] Other assignments: Adviser to Graduate Students, Boston University Art Gallery, 2010-2011; Director of Graduate Studies, 1993-94; Director, BU Art Gallery, 1980-89; Director, Museum Studies Program, 1980-91 Affiliated Faculty Member: American and New England Studies Program; African American Studies Program April-July 2013 Terra Foundation Visiting Professor, J. F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Freie Universität, Berlin 9/74 - 7/87 Adjunct Curator, 18th- & 19th-C Art, Whitney Museum of Am. Art, NY 6/81 C. V. Whitney Lectureship, Summer Institute of Western American Studies, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming 9/74 - 8/78 Asso. Prof., Fine Arts/Performing Arts, York College, City University of New York, Queens, and PhD Program in Art History, Graduate Center. 1-6/75 Adjunct Asso. Prof. Grad. School of Arts & Science, Columbia Univ. 1/72-9/74 Asso. -

A Pioneer Artist on Lake Superior

A PIONEER ARTIST ON LAKE SUPERIOR ON JANUARY 18, 1940, the Brooklyn Museum placed on display the first comprehensive collection ever assembled of the works of Eastman Johnson. Newspapers and periodi cals throughout the nation commented on the exhibit in their art columns, and at least one critic expressed surprised de light over a series of Indian sketches made on Lake Su perior.^ Six of the seven pictures in this group were loaned to the Brooklyn Museum for the Johnson exhibit by the St. Louis County Historical Society of Duluth, which has in its collections thirty-two paintings and sketches of Lake Su perior scenes and figures by this distinguished American portrait and genre painter. The story of Johnson's visits to the Head of Lake Su perior in 1856 and 1857, when he painted his western pic tures, and of the return of most of these pictures to the region of their origin forms an important chapter in the history of Minnesota art. When he made his first excur sion to the West, Johnson was a young man of thirty-two who had already experienced a measure of success as a por trait artist and who had enjoyed the advantages of six years of study abroad. In Augusta, Maine, and in Washington and Boston, he had filled orders for numerous portraits in pencil, crayon, and pastel. Among his subjects were such celebrities as Mrs. James Madison, Daniel Webster, and members of the Longfellow family.^ ^ For reviews of the Johnson exhibit, see, for example, the New York Times of January 21, Newsweek for January 22, and the New Yorker for February 3, 1940. -

Read Book American Wilderness the Story of the Hudson River School

AMERICAN WILDERNESS THE STORY OF THE HUDSON RIVER SCHOOL OF PAINTING 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kevin J Avery | 9781883789572 | | | | | American Wilderness The Story of the Hudson River School of Painting 1st edition PDF Book Here, he painted many of his Hudson River School works of art, eventually marrying the niece of Cedar Grove's owner and relocating to the area permanently. In a period of six years, Reed had assembled a significant collection of European and American art, which he displayed in a two- room gallery in his lower Manhattan home on Greenwich Street. SKU Morse In , Cole, then a calico designer, had a cordial meeting with Doughty, in Philadelphia, and the men encouraged each other to follow their aesthetic interest. In retrospect the main benefit to Cole of returning to England was seeing paintings by J. One of the uncles, Alexander Thomson, continued ownership, and the Coles shared living space with the Thomson family. Artists with a connection to these places:. Sign In. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica Encyclopaedia Britannica's editors oversee subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge, whether from years of experience gained by working on that content or via study for an advanced degree However, recognition of the key roles of these early Hudson River painters in our fine-art heritage is increasing. Members included William Cullen Bryant , prominent literary figure, and historical-genre painter Samuel S. An American art journal called The Crayon, published between and , reinforced the Hudson River School painters and promoted the idea that nature was a healing place for the human spirit. -

Art-Related Archival Materials in the Chicago Area

ART-RELATED ARCHIVAL MATERIALS IN THE CHICAGO AREA Betty Blum Archives of American Art American Art-Portrait Gallery Building Smithsonian Institution 8th and G Streets, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20560 1991 TRUSTEES Chairman Emeritus Richard A. Manoogian Mrs. Otto L. Spaeth Mrs. Meyer P. Potamkin Mrs. Richard Roob President Mrs. John N. Rosekrans, Jr. Richard J. Schwartz Alan E. Schwartz A. Alfred Taubman Vice-Presidents John Wilmerding Mrs. Keith S. Wellin R. Frederick Woolworth Mrs. Robert F. Shapiro Max N. Berry HONORARY TRUSTEES Dr. Irving R. Burton Treasurer Howard W. Lipman Mrs. Abbott K. Schlain Russell Lynes Mrs. William L. Richards Secretary to the Board Mrs. Dana M. Raymond FOUNDING TRUSTEES Lawrence A. Fleischman honorary Officers Edgar P. Richardson (deceased) Mrs. Francis de Marneffe Mrs. Edsel B. Ford (deceased) Miss Julienne M. Michel EX-OFFICIO TRUSTEES Members Robert McCormick Adams Tom L. Freudenheim Charles Blitzer Marc J. Pachter Eli Broad Gerald E. Buck ARCHIVES STAFF Ms. Gabriella de Ferrari Gilbert S. Edelson Richard J. Wattenmaker, Director Mrs. Ahmet M. Ertegun Susan Hamilton, Deputy Director Mrs. Arthur A. Feder James B. Byers, Assistant Director for Miles Q. Fiterman Archival Programs Mrs. Daniel Fraad Elizabeth S. Kirwin, Southeast Regional Mrs. Eugenio Garza Laguera Collector Hugh Halff, Jr. Arthur J. Breton, Curator of Manuscripts John K. Howat Judith E. Throm, Reference Archivist Dr. Helen Jessup Robert F. Brown, New England Regional Mrs. Dwight M. Kendall Center Gilbert H. Kinney Judith A. Gustafson, Midwest -

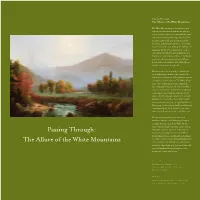

Passing Through: the Allure of the White Mountains

Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains The White Mountains presented nineteenth- century travelers with an American landscape: tamed and welcoming areas surrounded by raw and often terrifying wilderness. Drawn by the natural beauty of the area as well as geologic, botanical, and cultural curiosities, the wealthy began touring the area, seeking the sublime and inspiring. By the 1830s, many small-town tav- erns and rural farmers began lodging the new travelers as a way to make ends meet. Gradually, profit-minded entrepreneurs opened larger hotels with better facilities. The White Moun- tains became a mecca for the elite. The less well-to-do were able to join the elite after midcentury, thanks to the arrival of the railroad and an increase in the number of more affordable accommodations. The White Moun- tains, close to large East Coast populations, were alluringly beautiful. After the Civil War, a cascade of tourists from the lower-middle class to the upper class began choosing the moun- tains as their destination. A new style of travel developed as the middle-class tourists sought amusement and recreation in a packaged form. This group of travelers was used to working and commuting by the clock. Travel became more time-oriented, space-specific, and democratic. The speed of train travel, the increased numbers of guests, and a widening variety of accommodations opened the White Moun- tains to larger groups of people. As the nation turned its collective eyes west or focused on Passing Through: the benefits of industrialization, the White Mountains provided a nearby and increasingly accessible escape from the multiplying pressures The Allure of the White Mountains of modern life, but with urban comforts and amenities. -

Lackawanna Valley

MAN and the NATURAL WORLD: ROMANTICISM (Nineteenth-Century American Landscape Painting) NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN LANDSCAPE PAINTING Online Links: Thomas Cole – Wikipedia Hudson River School – Wikipedia Frederic Edwin Church – Wikipedia Cole's Oxbow – Smarthistory Cole's Oxbow (Video) – Smarthistory Church's Niagara and Heart of the Andes - Smarthistory Thomas Cole. The Oxbow (View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm), 1836, oil on canvas Thomas Cole (1801-1848) was one of the first great professional landscape painters in the United States. Cole emigrated from England at age 17 and by 1820 was working as an itinerant portrait painter. With the help of a patron, he traveled to Europe between 1829 and 1832, and upon his return to the United States he settled in New York and became a successful landscape painter. He frequently worked from observation when making sketches for his paintings. In fact, his self-portrait is tucked into the foreground of The Oxbow, where he stands turning back to look at us while pausing from his work. He is executing an oil sketch on a portable easel, but like most landscape painters of his generation, he produced his large finished works in the studio during the winter months. Cole painted this work in the mid- 1830s for exhibition at the National Academy of Design in New York. He considered it one of his “view” paintings because it represents a specific place and time. Although most of his other view paintings were small, this one is monumentally large, probably because it was created for exhibition at the National Academy. -

Download 1 File

n IMITHSONIAN^INSTITUTION NOIinillSNI^NVINOSHllWS S3iavaail LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN~INSTITUTION jviNOSHiiws ssiavaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniusNi nvinoshiiws ssiavaan in 2 , </> Z W iMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION ^NOIinillSNI NVINOSHilWS S3 I y Vy a \1 LI B RAR I ES^SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION jvinoshiiws S3iavaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniusNi nvinoshiiws ssiavaan 2 r- Z r z mithsonian~institution NoiiniusNi nvinoshiiws ssiyvyan libraries" smithsonian~institution 3 w \ivinoshiiws 's3 iavaan~LiBRARi es"smithsonian~ institution NoiiniusNi nvinoshiiws"'s3 i a va a 5 _ w =£ OT _ smithsonian^institution NoiiniiiSNrNViNOSHiiws S3 lavaan librari es smithsonian~institution . nvinoshiiws ssiavaan libraries Smithsonian institution NouruiiSNi nvinoshjliws ssiavaan w z y to z • to z u> j_ i- Ul US 5s <=> Yfe ni nvinoshiiws Siiavyan libraries Smithsonian institution NouniiisNi_NviNOSHiiws S3iava LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITU1 ES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIifUllSNI NVINOSHJLIWS S3 I a Va an |NSTITUTION„NOIinillSNI_NVINOSHllWS^S3 I H VU SNI NVINOSH1IWS S3 I ava 8 II LI B RAR I ES..SMITHSONIAN % Es"SMITHSONIAN^INSTITUTION"'NOIinillSNrNVINOSHllWS ''S3IHVHan~LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN_INSTITU OT 2 2 . H <* SNlZWlNOSHilWslsS lavaail^LIBRARI ES^SMITHSONIAN]jNSTITUTION_NOIinil±SNI _NVINOSHllWS_ S3 I UVh r :: \3l ^1) E ^~" _ co — *" — ES "SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION^NOIinillSNI NVINOSH1IWS S3iavaail LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITU '* CO z CO . Z "J Z \ SNI NVINOSHJ.IWS S3iavaan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinil±SNI_NVINOSH±IWS S3 I HVi Nineteenth-Century