I REJUVENATING the DWINDLING IMAGE of ORANGE GROVE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

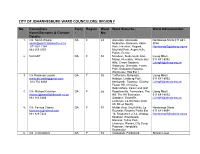

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Braamfontein Aims to Be National Digital Hub

Views, Comments and Opinion Braamfontein aims to be national digital hub by Hans van de Groenendaal, features editor Prof. Barry Dwolatzky, director of the the Joburg Centre for Sofware Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand believes in the value of an attractive and vibrant digital technolgy hub in Braamfontein to support skills development, job creation, entrepreneurship and the rejuvenation of Johanesburg's inner city. Braamfontein has seen much urban renewal in recent times, and is begining to regain its erstwhile trendiness. Prof. Barry Dwolatzky calls this new digital development the Tshimologong Precinct and is planning to create an exciting new-age software skills and innovation hub. Tshimologong is the seSotho for "place of new beginnings". The precinct is part of an ambitious ICT cluster development programme, Tech-in-Braam, aimed at turning the once dilapidated suburb into the new technical heart of South Africa and beyond. Prof. Dwolatzky is in the process of setting up shop in a series of five unused buildings. After some extensive refurbishments, a one-time night club floor will become a meeting space and will house server rooms; warehouses will be converted into computer labs and retail outlets will reincarnate as development pods. Braamfontein’s many advantages have made the neighbourhood an obvious The Tshimologong precinct will be developed in this part of Braamfontein. location for the precinct – it is convenient to two universities (the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Johannesburg); it is centrally located with good public transport; it is the site of local government departments and many non-governmental organisations; and it is within easy reach of banks and mining houses, as well as a multitude of corporate headquarters. -

City of Johannesburg Pikitup

City of Johannesburg Pikitup Pikitup Head Office Private Bag X74 Tel +27(0) 11 712 5200 66 Jorissen Place, Jorissen St, Braamfontein Fax +27(0) 11 712 5322 Braamfontein Johannesburg www.pikitup.co.za 2017 2017 www.joburg.org.za DEPOT SUBURB/TOWNSHIP PRIORITY AREAS TO BE CLEARED ON FRIDAY, 05 FEB 2016 AVALON DEPOT Eldorado Park Ext 2 and Eldorado Park Proper (Michael Titus 083 260 1776) Eldorado Park Ext 10 and Proper Eldorado Park Ext 1, 3, and Bushkoppies Eldorado Park Ext 6 and 4 Eldorado Park Ext 4, Proper and Nancefield Industria Eldorado Park Ext 2, 3 and Bushkoppies Eldorado Park Ext 4 and Proper Eldorado Park Proper and M/Park Orange Farm Ext 3 and 1 Orange Farm Ext 1 and 2 Orange Farm Ext 1 and 2 Orange Farm Proper CENTRAL CAMP Selinah Pimville Zones 1 - 4 Tshablala 071 8506396 MARLBORO DEPOT Buccleuch ‘Nyane Motaung - 071 850 6395 Sandown City of Johannesburg Pikitup Pikitup Head Office Private Bag X74 Tel +27(0) 11 712 5200 66 Jorissen Place, Jorissen St, Braamfontein Fax +27(0) 11 712 5322 Braamfontein Johannesburg www.pikitup.co.za 2017 2017 www.joburg.org.za MIDRAND DEPOT Cresent wood, Erands gardens, Erands AH and Noordwyk South Jeffrey Mahlangu 082 492 8893 Juskeyview, Waterval estate, South , west and north NORWOOD DEPOT Bruma (Neil Observatory Macherson 071 Kensington 682 1450) Yeoville RANDBURG DEPOT Majoro Letsela Blairgowrie 082 855 9348 ROODEPOORT DEPOT Stella Wilson - Florida 071 856 6822 SELBY DEPOT Fordsburg Sobantwana Mkhuseli CBD 1: (Noord to Commissioner & End to Rissik Streets) 082 855 9321 CBD 2: (Rissik to -

DOORNFONTEIN and ITS AFRICAN WORKING CLASS, 1914 to 1935*• a STUDY of POPULAR CULTURE in JOHANNESBURG Edward Koch a Dissertati

DOORNFONTEIN AND ITS AFRICAN WORKING CLASS, 1914 TO 1935*• A STUDY OF POPULAR CULTURE IN JOHANNESBURG Edward Koch I A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Arts University of the witwatersrand, Johannesburg for the Degree of Master of Arts. Johannesburg 1983. Fc Tina I declare that this dissertation is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in the University of the Wlj Witwaterirand Johanneaourg. It has not been submitted before for any H 1 9 n degree or examination- in any other University. till* dissertation is a study of the culture that was made by tha working people who lived in the slums of Johannesburg in the inter war years. This was a period in which a large proportion of the city's black working classes lived in slums that spread across the western, central and eastern districts of the central city area E B 8 mKBE M B ' -'; of Johannesburg. Only after the mid 1930‘s did the state effectively segregate the city and move most of the black working classes to the municipal locations that they live in today. The culture that was created in the slums of Johannesburg is significant for a number of reasons. This culture shows that the newly formed 1 urban african classes wore not merely the passive agents of capitalism. These people were able to respond, collectively, to the conditions that the development of capitalism thrust them into and to shape and influence the conditions and pro cesses that they were subjected to. The culture that embodied these popular res ponses was so pervasive that it's name, Marabi, is also the name given by many people to the era, between the two world wars, when it thrived. -

Memories of Johannesburg, City of Gold © Anne Lapedus

NB This is a WORD document, you are more than Welcome to forward it to anyone you wish, but please could you forward it by merely “attaching” it as a WORD document. Contact details For Anne Lapedus Brest [email protected] [email protected]. 011 783.2237 082 452 7166 cell DISCLAIMER. This article has been written from my memories of S.Africa from 48 years ago, and if A Shul, or Hotel, or a Club is not mentioned, it doesn’t mean that they didn’t exist, it means, simply, that I don’t remember them. I can’t add them in, either, because then the article would not be “My Memories” any more. MEMORIES OF JOHANNESBURG, CITY OF GOLD Written and Compiled By © ANNE LAPEDUS BREST 4th February 2009, Morningside, Sandton, S.Africa On the 4th February 1961, when I was 14 years old, and my brother Robert was 11, our family came to live in Jhb. We had left Ireland, land of our birth, leaving behind our beloved Grandparents, family, friends, and a very special and never-to-be-forgotten little furry friend, to start a new life in South Africa, land of Sunshine and Golden opportunity…………… The Goldeneh Medina…... We came out on the “Edinburgh Castle”, arriving Cape Town 2nd Feb 1961. We did a day tour of Chapmans Peak Drive, Muizenberg, went to somewhere called the “Red Sails” and visited our Sakinofsky/Yodaiken family in Tamboerskloof. We arrived at Park Station (4th Feb 1961), Jhb, hot and dishevelled after a nightmarish train ride, breaking down in De Aar and dying of heat. -

Department of Human Settlements Government Gazette No

Reproduced by Data Dynamics in terms of Government Printers' Copyright Authority No. 9595 dated 24 September 1993 671 NO. 671 NO. Priority Housing Development Areas Department of Human Settlements Housing Act (107/1997): Proposed Priority Housing Development Areas HousingDevelopment Priority Proposed (107/1997): Act Government Gazette No.. I, NC Mfeketo, Minister of Human Settlements herewith gives notice of the proposed Priority Housing Development Areas (PHDAs) in terms of Section 7 (3) of the Housing Development Agency Act, 2008 [No. 23 of 2008] read with section 3.2 (f-g) of the Housing Act (No 107 of 1997). 1. The PHDAs are intended to advance Human Settlements Spatial Transformation and Consolidation by ensuring that the delivery of housing is used to restructure and revitalise towns and cities, strengthen the livelihood prospects of households and overcome apartheid This gazette isalsoavailable freeonlineat spatial patterns by fostering integrated urban forms. 2. The PHDAs is underpinned by the principles of the National Development Plan (NDP) and allied objectives of the IUDF which includes: DEPARTMENT OFHUMANSETTLEMENTS DEPARTMENT 2.1. Spatial justice: reversing segregated development and creation of poverty pockets in the peripheral areas, to integrate previously excluded groups, resuscitate declining areas; 2.2. Spatial Efficiency: consolidating spaces and promoting densification, efficient commuting patterns; STAATSKOERANT, 2.3. Access to Connectivity, Economic and Social Infrastructure: Intended to ensure the attainment of basic services, job opportunities, transport networks, education, recreation, health and welfare etc. to facilitate and catalyse increased investment and productivity; 2.4. Access to Adequate Accommodation: Emphasis is on provision of affordable and fiscally sustainable shelter in areas of high needs; and Departement van DepartmentNedersettings, of/Menslike Human Settlements, 2.5. -

A Case Study on South Africa's First Shipping Container Shopping

Local Public Space, Global Spectacle: A Case Study on South Africa’s First Shipping Container Shopping Center by Tiffany Ferguson BA in Dance BA Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Urban America Hunter College of the City University of New York (2010) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2018 © 2018 Tiffany Ferguson. All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author____________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 24, 2018 Certified by_________________________________________________________________ Assistant Professor of Political Economy and Urban Planning, Jason Jackson Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by________________________________________________________________ Professor of the Practice, Ceasar McDowell Department of Urban Studies and Planning Chair, MCP Committee 2 Local Public Space, Global Spectacle: A Case Study on South Africa’s First Shipping Container Shopping Center by Tiffany Ferguson Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 24, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning Abstract This thesis is the explication of a journey to reconcile Johannesburg’s aspiration to become a ‘spatially just world class African city’ through the lens of the underperforming 27 Boxes, a globally inspired yet locally contested retail center in the popular Johannesburg suburb of Melville. By examining the project’s public space, market, retail, and design features – features that play a critical role in its imagined local economic development promise – I argue that the project’s ‘failure’ can be seen through a prism of factors that are simultaneously local and global. -

Melville, Johannesburg

SUPPORTING A COMMUNITY THROUGH DESIGN: MELVILLE, JOHANNESBURG Christa VAN ZYL University of Johannesburg Abstract In 2012 the Melville Community Development Organisation (MCDO) approached the Department of Strategic Communications at the University of Johannesburg for a collaboration between the University and the Melville community, with the support of the Melville Residence Association (MRA). These Melville institutions requested groups of Honours students to research and propose a solution for the urban degeneration within the area, as perceived by its businesses, tourists and residents. After extensive research the majority of the Honours students in Strategic Communications recommended that Melville should follow in the footsteps of the DĂĚŝďĞŶŐ ĂƌĞĂ ĂŶĚ ƌĂĂŵĨŽŶƚĞŝŶ͕ ďŽƚŚ ŝŶ :ŽŚĂŶŶĞƐďƵƌŐ͛Ɛ ĐĞŶƚƌĂů ďƵƐŝŶĞƐƐ ĚŝƐƚƌŝĐƚ͕ ĂƐ ǁĞůů ĂƐ ŽƚŚĞƌ intĞƌŶĂƚŝŽŶĂůĞdžĂŵƉůĞƐůŝŬĞ>ŽŶĚŽŶ͛ƐĂŵĚĞŶdŽǁŶĂŶĚKǀĞƌŚŽĞŬƐ͕ŵƐƚĞƌĚĂŵ͕ƚŽĚĞƐŝŐŶĂďƌĂŶĚĨŽƌƚŚĞĂƌĞĂ͘ dŚĞ hŶŝǀĞƌƐŝƚLJ ŽĨ :ŽŚĂŶŶĞƐďƵƌŐ͛Ɛ ĞƉĂƌƚŵĞŶƚ ŽĨ 'ƌĂƉŚŝĐ ĞƐŝŐŶ dĞĐŚ ĐůĂƐƐ ŽĨ ϮϬϭϯ ǁĂƐ ĐŽŶƐĞƋƵĞŶƚůLJ approached to apply the research in the form of a brand for Melville. From interviews with various stakeholders and interested parties within Melville, however, it became clear the community's more settled bohemian residents pride themselves on their individualism, and that they would not be open to one singular brand for their suburb. Their response correlated with a similar reaction in Hamburg, Germany, where residents openly rebelled against what they perceived as a brand that was enforced on their community without their approval (Beckman & Zenker 2012). The interviews also confirmed the theory of user experience design that socially responsible design should in practice not be about the designer, but rather about the experiences of the community utilising and viewing the designs. The sixteen Graphic Design students were thus tasked with identifying an existing challenge or community initiative and its stakeholders, with the help of the MCDO and MRA. -

35885 23-11 Legalap1 Layout 1

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA Vol. 569 Pretoria, 23 November 2012 No. 35885 PART 1 OF 2 LEGAL NOTICES A WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 201513—A 35885—1 2 No. 35885 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 23 NOVEMBER 2012 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. TABLE OF CONTENTS LEGAL NOTICES Page BUSINESS NOTICES.............................................................................................................................................. 11 Gauteng..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Eastern Cape............................................................................................................................................ -

Live Music Audiences Johannesburg (Gauteng) South Africa

Live Music Audiences Johannesburg (Gauteng) South Africa 1 Live Music and Audience Development The role and practice of arts marketing has evolved over the last decade from being regarded as subsidiary to a vital function of any arts and cultural organisation. Many organisations have now placed the audience at the heart of their operation, becoming artistically-led, but audience-focused. Artistically-led, audience-focused organisations segment their audiences into target groups by their needs, motivations and attitudes, rather than purely their physical and demographic attributes. Finally, they adapt the audience experience and marketing approach for each target groupi. Within the arts marketing profession and wider arts and culture sector, a new Anglo-American led field has emerged, called audience development. While the definition of audience development may differ among academics, it’s essentially about: understanding your audiences through research; becoming more audience-focused (or customer-centred); and seeking new audiences through short and long-term strategies. This report investigates what importance South Africa places on arts marketing and audiences as well as their current understanding of, and appetite for, audience development. It also acts as a roadmap, signposting you to how the different aspects of the research can be used by arts and cultural organisations to understand and grow their audiences. While audience development is the central focus of this study, it has been located within the live music scene in Johannesburg and wider Gauteng. Emphasis is also placed on young audiences as they represent a large existing, and important potential, audience for the live music and wider arts sector. -

DANNY MYBURGH DATE of BIRTH 20 June 1962 ID NUMBER 620620

DANNY MYBURGH DATE OF BIRTH 20 June 1962 ID NUMBER 620620 0144 084 ADDRESS 10 Armagh Road Parkview Johannesburg 2193 South Africa CELLPHONE +27 82 881 7516 EMAIL [email protected] WEBSITE www.dannymyburgh.co.za MARITAL STATUS married to Craig Watt-Pringle with 2 sons, Simon 25 and Thomas 22 MATRICULATED 1980 St Mary’s School for Girls Waverly Johannesburg South Africa UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH South Africa 1981-1985 BA (Law) UNISA South Africa 1995-1996 History of Art THE ART THERAPY CENTRE – LEFIKA LA PHODISA Johannesburg South Africa 1998-2002, Certificate in Community Art Therapy 2002-2004 Project manager, The Art Therapy Centre – Lefika la Phodisa, Rosebank Johannesburg South Africa 2004-2007 Art therapist, Johannesburg Parent and Child Counselling Centre, Berea Johannesburg South Africa 2007-2012 Head of Art Department, The Ridge School, Westcliff Johannesburg South Africa 2012 - present Artist in residence at The Bag Factory, Fordsburg Johannesburg 2016 - present founded Editions art gallery EXHIBITIONS 2014 Turbine Art Fair, Newtown, Johannesburg 2014 Joburg Art Fair, Sandton, Johannesburg 2014 Solo exhibition Container/Contained, The Bag Factory, Fordsburg, Johannesburg 2014 Salon 1 group exhibition, Bamboo Centre, Melville, Johannesburg 2015 In Toto art gallery group exhibition, Birdhaven, Johannesburg South Africa 2015 Turbine Art Fair Newtown Johannesburg 2015 Johannesburg Art Fair Sandton Johannesburg 2015 Transitions at the Post Office group exhibition, Vrededorp ,Johannesburg South Africa 2016 Cape Town Art Fair 2016 The Bag Factory Salon Sale Fordsburg Johannesburg South Africa 2016 Hermanus FynArts festival South Africa, joint show with Terry Kobus 2016 Joburg Fringe at August House, Doornfontein, Johannesburg, group show COLLECTIONS Michaelis Art Library Johannesburg CURATOR 2015 Transitions at the Post Office Vrededorp Johannesburg 2016 Joburg Fringe at August House, Doornfontein, Johannesburg RESIDENCY 2015 Vallauris AIR Vallauris Alpes Maritime France . -

Property Vacancy Schedule

Property Vacancy Schedule August 2019 Gauteng - GLA Western Cape - GLA Other Provinces - GLA Contact Phone Office 46,997 345 7,000 Roddy Watson 071 351 5437 Industrial 128,599 0 14,662 Daniel des Tombe 072 535 0942 Retail 4,784 506 855 Burger Bothma 073 369 6282 Property Vacancy Schedule August 2019 Viewings by appointment only Back to Index Roddy Watson (RW) | 071 351 5437 | [email protected] Leasing: 011 286 9152 Gauteng Office Rate per m2 Property Vacancy size Address Region Building Floor Parking Availability Additional comments Keys Contact name (m²) Gross Net Operational Assessment rental rental cost rates Rivonia 345 Rivonia 345 Rivonia Road, Rivonia JHB 1,200 Ground floor R 135.00 R 96.35 R 24.77 R 13.88 R 650.00 Immediate Generator Backup With security RW Rosebank The Firs Biermann Road, Rosebank JHB 681 3rd floor R 190.00 R 125.00 R 34.00 R 31.00 R 1,150.00 one months notice Generator and water back up Management office RW JHB 529 1st floor R 190.00 R 125.00 R 34.00 R 31.00 R 1,150.00 Immediate Generator and water back up Management office RW JHB 565 2nd floor R 190.00 R 125.00 R 34.00 R 31.00 R 1,150.00 Immediate Generator and water back up Management office RW JHB 952 2nd floor R 190.00 R 125.00 R 34.00 R 31.00 R 1,150.00 Immediate Generator and water back up Management office RW Midrand Shaded parking (283 40:60 office to warehouse split.