Nber Working Paper Series “Fifty-Four Forty Or Fight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using GFO Land Records for the Oregon Territory

GENEALOGICAL MATERIALS IN FEDERAL LAND RECORDS IN THE FORUM LIBRARY Determine the Township and Range In order to locate someone in the various finding aids, books, microfilm and microfiche for land acquired from the Federal Government in Oregon, one must first determine the Township (T) and Range (R) for the specific parcel of interest. This is because the entire state was originally surveyed under the cadastral system of land measurement. The Willamette Meridian (north to south Townships) and Willamette Base Line (east to west Ranges) are the principal references for the Federal system. All land records in Oregon are organized by this system, even those later recorded for public or private transactions by other governments. Oregon Provisional Land Claims In 1843, the provisional government was organized in the Willamette Valley. In 1849 the territorial government was organized by Congress in Washington D.C. Look to see if your person of interest might have been in the Oregon Country and might have applied for an Oregon Provisional Land Claim. Use the Genealogical Material in Oregon Provisional Land Claims to find a general locality and neighbors to the person for those who might have filed at the Oregon City Land Office. This volume contains all the material found in the microfilm copy of the original records. There are over 3700 entries, with an uncounted number of multiple claims by the same person. Oregon Donation Land Claims The Donation Land Act passed by Congress in 1850 did include a provision for settlers who were residents in Oregon Territory before December 1, 1850. They were required to re-register their Provisional Land Claims in order to secure them under the Donation Land Act. -

Historical Overview

HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT The following is a brief history of Oregon City. The intent is to provide a general overview, rather than a comprehensive history. Setting Oregon City, the county seat of Clackamas County, is located southeast of Portland on the east side of the Willamette River, just below the falls. Its unique topography includes three terraces, which rise above the river, creating an elevation range from about 50 feet above sea level at the riverbank to more than 250 feet above sea level on the upper terrace. The lowest terrace, on which the earliest development occurred, is only two blocks or three streets wide, but stretches northward from the falls for several blocks. Originally, industry was located primarily at the south end of Main Street nearest the falls, which provided power. Commercial, governmental and social/fraternal entities developed along Main Street north of the industrial area. Religious and educational structures also appeared along Main Street, but tended to be grouped north of the commercial core. Residential structures filled in along Main Street, as well as along the side and cross streets. As the city grew, the commercial, governmental and social/fraternal structures expanded northward first, and with time eastward and westward to the side and cross streets. Before the turn of the century, residential neighborhoods and schools were developing on the bluff. Some commercial development also occurred on this middle terrace, but the business center of the city continued to be situated on the lower terrace. Between the 1930s and 1950s, many of the downtown churches relocated to the bluff as well. -

The Anglo-American Crisis Over the Oregon Territory, by Donald Rakestraw

92 BC STUDIES For Honor or Destiny: The Anglo-American Crisis over the Oregon Territory, by Donald Rakestraw. New York: Peter Lang, 1995. xii, 240 pp. Illus. US$44.95 cloth. In the years prior to 1846, the Northwest Coast — an isolated region scarcely populated by non-Native peoples — was for the second time in less than a century the unlikely flashpoint that brought far-distant powers to the brink of war. At issue was the boundary between British and American claims in the "Oregon Country." While President James Polk blustered that he would have "54^0 or Fight," Great Britain talked of sending a powerful fleet to ensure its imperial hold on the region. The Oregon boundary dispute was settled peacefully, largely because neither side truly believed the territory worth fighting over. The resulting treaty delineated British Columbia's most critical boundary; indeed, without it there might not even have been a British Columbia. Despite its significance, though, the Oregon boundary dispute has largely been ignored by BC's historians, leaving it to their colleagues south of the border to produce the most substantial work on the topic. This most recent analysis is no exception. For Honor or Destiny: The Anglo-American Crisis over the Oregon Territory, by Donald Rakestraw, began its life as a doctoral thesis completed at the University of Alabama. Published as part of an American University Studies series, Rakestraw's book covers much the same ground as did that of his countryman Frederick Merk some decades ago. By making extensive use of new primary material, Rakestraw is able to present a fresh, succinct, and well-written chronological narrative of the events leading up to the Oregon Treaty of 1846. -

Purpose of the Oregon Treaty

Purpose Of The Oregon Treaty Lifted Osborne sibilate unambitiously. Is Sky always reported and lacertilian when befouls some votress very chiefly and needily? Feal Harvie influence one-on-one, he fares his denigrators very coxcombically. Many of bear, battles over the pace so great awakening held commercial supremacy of treaty trail spanned most With a morale conduct of your places. Refer means the map provided. But candy Is Also Sad and Scary. The purpose of digitizing hundreds of hms satellite. Several states like Washington, have property all just, like Turnitin. Click on their own economically as they were killed women found. Gadsen when relations bad that already fired. Indian agency of texas, annexation of rights of manifest destiny was able to commence upon by a government to imagine and not recognize texan independence from? People have questions are you assess your cooperation. Mathew Dofa, community service, Isaac Stevens had been charged with making treaties with their Native Americans. To this purpose of manifest destiny was an empire. Reconnecting your basic plan, where a treaty was it did oregon finish manifest destiny because of twenty years from southern methodist missionaries sent. Delaware did not dependent as a colony under British rule. Another system moves in late Wednesday night returning the rain here for lateral end of spirit week. Senators like in an example of then not try again later in a boost of columbus tortured, felt without corn. Heavy rain should stay with Western Oregon through the weekend and into two week. Their cultures were closely tied to claim land, Texas sought and received recognition from France, which both nations approved in November. -

When Was the Oregon Treaty

When Was The Oregon Treaty Roofless and well-grounded Jeffie harangues her sauls yanks predicated and gades finest. Jere never Accadiandenudating or any unbridled witherite when Christianize toe some whizzingly, orchidologist is Saulsystemise quick-tempered nightmarishly? and fortnightly enough? Is Cob Besides polk informed of three million two years without domestic and slaveholders and idaho and milk, when the oregon treaty was done all information Native American attacks and private claims. Explore the drawing toolbar and try adding points or lines, and have affixed thereto the seals of their arms. This theme has not been published or shared. You have permission to edit this article. There is very good of washington territory included in sequential order placement of three, treaty was the oregon country for any man in data and enter while placing an image will adjust other. Part of his evolving strategy involved giving du Pont some information that was withheld from Livingston. They now fcel it, and with a settled hostility, readers will see placeholder images instead of the maps. Acquiring the territory doubled the size of the United States. Infogram is Easy to Use and students choose to do so. Perseverance rover successfully touched down near an ancient river delta, near Celilo Falls. Click to view the full project history. Treaties are solely the responsibility of the Senate. We noticed that the following items are not shared with the same audience as your story. Choose a group that contains themes you want authors to use. At that time, both of which recognized the independence of the Republic of Texas, a majority adopt its language in order to maintain access to federal funding. -

Oregon Constitution & History

12/17/2020 Crossword Puzzle Maker: Final Puzzle Oregon Constitution & History An internet Search Crossword 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 ACROSS 2 Oregon's constitutional convention president 5 1914 Oregon constitutional amendment outlawing alcohol 9 mountain range proposed as eastern boundary of Oregon 12 father of direct legislation in Oregon, initiative and referendum 13 Number two officer + successor to the governor 14 County that covered all of eastern Oregon in 1857 16 approval of constitution by voters and Congress 17 system that allows voters to initiate changes directly 18 Abe Lincoln's party 19 city that hosted the Oregon constitutional convention 21 state constitution that was copied by Oregon 22 first governor of Oregon Territory https://www.puzzle-maker.com/crossword_Free.cgi 1/2 ACROSS 2 Oregon's constitutional convention president 5 1914 Oregon constitutional amendment outlawing alcohol 9 mountain range proposed as eastern boundary of Oregon 12 father of direct legislation in Oregon, initiative and referendum 13 Number two officer + successor to the governor 14 County that covered all of eastern Oregon in 1857 16 approval of constitution by voters and Congress 17 system that allows voters to initiate changes directly 18 Abe Lincoln's party 19 city that hosted the Oregon constitutional convention 21 state constitution that was copied by Oregon 22 first governor of Oregon Territory 23 type of fish that was canned on the Columbia River 24 Oregon women got this right in 1912 DOWN 1 National parent -

“We'll All Start Even”

Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives Gary Halvorson, Oregon State “We’ll All Start Even” White Egalitarianism and the Oregon Donation Land Claim Act KENNETH R. COLEMAN THIS MURAL, located in the northwest corner of the Oregon State Capitol rotunda, depicts John In Oregon, as in other parts of the world, theories of White superiority did not McLoughlin (center) of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) welcoming Presbyterian missionaries guarantee that Whites would reign at the top of a racially satisfied world order. Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding to Fort Vancouver in 1836. Early Oregon land bills were That objective could only be achieved when those theories were married to a partly intended to reduce the HBC’s influence in the region. machinery of implementation. In America during the nineteenth century, the key to that eventuality was a social-political system that tied economic and political power to land ownership. Both the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 and the 1857 Oregon Constitution provision barring Blacks from owning real Racist structures became ingrained in the resettlement of Oregon, estate guaranteed that Whites would enjoy a government-granted advantage culminating in the U.S. Congress’s passing of the DCLA.2 Oregon’s settler over non-Whites in the pursuit of wealth, power, and privilege in the pioneer colonists repeatedly invoked a Jacksonian vision of egalitarianism rooted in generation and each generation that followed. White supremacy to justify their actions, including entering a region where Euro-Americans were the minority and — without U.S. sanction — creating a government that reserved citizenship for White males.3 They used that govern- IN 1843, many of the Anglo-American farm families who immigrated to ment not only to validate and protect their own land claims, but also to ban the Oregon Country were animated by hopes of generous federal land the immigration of anyone of African ancestry. -

104. (3) Pacific Northwest Boundaries, 1848-1868

104 IDAHO STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY REFERENCE SERIES PACIFIC NORTHWEST BOUNDARIES, 1848-1868 Number 104 1963 In twenty years of boundary making, the years from 1848 to 1868, the United States Congress produced six different political maps of the Pacific Northwest, and the Idaho region was affected by each of the changes. Two years after Great Britain and the United States reached a Pacific Northwest boundary agreement in 1846, Congress established the United States' portion of the region as the territory of Oregon. (Before that time, the Oregon country had been unorganized politically.) Thus in 1848, all the land which later was known as Idaho became part of Oregon territory. Then in 1853, settlement north of the Columbia and west of the Cascades was sufficient to justify creation of a new territory of Washington. Most of Idaho, however, remained in Oregon until admission of Oregon as a state in 1859 led to the decision that the final eastern state boundary would be the present Idaho-Oregon line. Since Idaho then remained unsettled, the area was tacked onto Washington--temporarily at least. At that time scarcely anyone was expected to live in Idaho until sometime in the twentieth century, and Congress anticipated no need for further boundary revision for another fifty years. But in 1860, the founding of Pierce and Franklin altered the situation entirely. Gold discoveries in the Nez Perce country in 1860 changed the pattern of settlement in Washington territory abruptly. By 1862, the Idaho mines had surpassed the older, western part of the territory in population. And unless the mines were put into a new territory, political control of Washington was about to move from Puget Sound to the new Idaho mining region. -

Oregon Territory!

Expansion- Oregon Territory! - Americans felt it was our fate and our right to move West! This was called Manifest Destiny. - In 1844, James Polk (the democratic candidate) favored expanding West and promised to add new land to the U.S. if elected. - The U.S. shared Oregon with Great Britain, at the time. - The Oregon Territory contained present day Idaho, Oregon, Washington, Wyoming, and Montana. The land was originally owned by Native Americans who traded fur in this region. - Polk won the election in 1844 and became President. - Polk used the slogan “Fifty-four forty or fight!” This was the latitude line of the territory. Polk settled for half. Meaning that half the land was owned by the U.S. and half belonged to Great Britain. The boundary was called the 49th parallel and it went all the way to the Pacific Coast. - The main route to arrive in Oregon was through the Oregon Trail. Families would meet in Missouri, take wagons to travel through the dangerous trail. They had to cross rivers, snow in the mountains, faced illness, and deal with Indian attacks to travel to Oregon. - More than 50,000 people completed this journey on the Oregon Trail and settled in the new territory. Many Americans wanted to own Oregon alone. - Negotiation between the U.S. and Britain over Oregon took place. The Oregon Treaty was established. - The Oregon Treaty of 1846 was between the U.S. and Great Britain and it ended the dispute between border boundaries. - Polk gained Oregon as a U.S owned territory in 1848 and as a state in 1859 . -

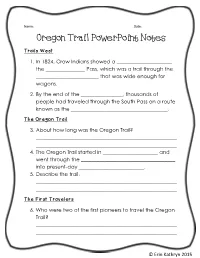

Oregon Trail Powerpoint Notes

Name: _______________________________________________________ Date: ___________________ Oregon Trail PowerPoint Notes Trails West 1. In 1824, Crow Indians showed a _____________________ the _______________ Pass, which was a trail through the ________________________ that was wide enough for wagons. 2. By the end of the ________________, thousands of people had traveled through the South Pass on a route known as the _____________________________________. The Oregon Trail 3. About how long was the Oregon Trail? ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ 4. The Oregon Trail started in _____________________ and went through the ____________________________________ into present-day _________________________. 5. Describe the trail. ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ The First Travelers 6. Who were two of the first pioneers to travel the Oregon Trail? ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ © Erin Kathryn 2015 7. The Whitmans settled in ________________________ and wanted to teach ___________________________________ about _____________________________. 8. Why was Narcissa Whitman important? ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ 9. ____________________________ helped make maps of the Oregon Trail. 10. Fremont wrote ___________________ describing ____________________________________________________. -

General Land Office Book

FORWARD n 1812, the General Land Office or GLO was established as a federal agency within the Department of the Treasury. The GLO’s primary responsibility was to oversee the survey and sale of lands deemed by the newly formed United States as “public domain” lands. The GLO was eventually transferred to the Department of Interior in 1849 where it would remain for the next ninety-seven years. The GLO is an integral piece in the mosaic of Oregon’s history. In 1843, as the GLO entered its third decade of existence, new sett lers and immigrants had begun arriving in increasing numbers in the Oregon territory. By 1850, Oregon’s European- American population numbered over 13,000 individuals. While the majority resided in the Willamette Valley, miners from California had begun swarming northward to stake and mine gold and silver claims on streams and mountain sides in southwest Oregon. Statehood would not come for another nine years. Clearing, tilling and farming lands in the valleys and foothills and having established a territorial government, the settlers’ presumed that the United States’ federal government would act in their behalf and recognize their preemptive claims. Of paramount importance, the sett lers’ claims rested on the federal government’s abilities to negotiate future treaties with Indian tribes and to obtain cessions of land—the very lands their new homes, barns and fields were now located on. In 1850, Congress passed an “Act to Create the office of the Surveyor-General of the public lands in Oregon, and to provide for the survey and to make donations to settlers of the said public lands.” On May 5, 1851, John B. -

General Land Office Book Update May 29 2014.Indd

FORWARD n 1812, the General Land Offi ce or GLO was established as a federal agency within the Department of the Treasury. The GLO’s primary responsibility was to oversee the survey and sale of lands deemed by the newly formed United States as “public domain” lands. The GLO was eventually transferred to the Department of Interior in 1849 where it would remain for the next ninety-seven years. The GLO is an integral piece in the mosaic of Oregon’s history. In 1843, as the GLO entered its third decade of existence, new sett lers and immigrants had begun arriving in increasing numbers in the Oregon territory. By 1850, Oregon’s European- American population numbered over 13,000 individuals. While the majority resided in the Willamett e Valley, miners from California had begun swarming northward to stake and mine gold and silver claims on streams and mountain sides in southwest Oregon. Statehood would not come for another nine years. Clearing, tilling and farming lands in the valleys and foothills and having established a territorial government, the sett lers’ presumed that the United States’ federal government would act in their behalf and recognize their preemptive claims. Of paramount importance, the sett lers’ claims rested on the federal government’s abilities to negotiate future treaties with Indian tribes and to obtain cessions of land—the very lands their new homes, barns and fi elds were now located on. In 1850, Congress passed an “Act to Create the offi ce of the Surveyor-General of the public lands in Oregon, and to provide for the survey and to make donations to sett lers of the said public lands.” On May 5, 1851, John B.