Anti-Racism Resource Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Jazz History and Research Graduate Program in Arts written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and Dr. Henry Martin And approved by Newark, New Jersey May 2016 ©2016 Zachary Streeter ALL RIGHT RESERVED ABSTRACT Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zach Streeter Thesis Director: Dr. Lewis Porter Despite the institutionalization of jazz music, and the large output of academic activity surrounding the music’s history, one is hard pressed to discover any information on the late jazz guitarist Jimmy Raney or the legacy Jimmy Raney left on the instrument. Guitar, often times, in the history of jazz has been regulated to the role of the rhythm section, if the guitar is involved at all. While the scope of the guitar throughout the history of jazz is not the subject matter of this thesis, the aim is to present, or bring to light Jimmy Raney, a jazz guitarist who I believe, while not the first, may have been among the first to pioneer and challenge these conventions. I have researched Jimmy Raney’s background, and interviewed two people who knew Jimmy Raney: his son, Jon Raney, and record producer Don Schlitten. These two individuals provide a beneficial contrast as one knew Jimmy Raney quite personally, and the other knew Jimmy Raney from a business perspective, creating a greater frame of reference when attempting to piece together Jimmy Raney. -

Resources on Race, Racism, and How to Be an Anti-Racist Articles, Books, Podcasts, Movie Recommendations, and More

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” – JAMES BALDWIN DIVERSITY & INCLUSION ————— Resources on Race, Racism, and How to be an Anti-Racist Articles, Books, Podcasts, Movie Recommendations, and More Below is a non-exhaustive list of resources on race, anti-racism, and allyship. It includes resources for those who are negatively impacted by racism, as well as resources for those who want to practice anti-racism and support diverse individuals and communities. We acknowledge that there are many resources listed below, and many not captured here. If after reviewing these resources you notice gaps, please email [email protected] with your suggestions. We will continue to update these resources in the coming weeks and months. EXPLORE Anguish and Action by Barack Obama The National Museum of African American History and Culture’s web portal, Talking About Race, Becoming a Parent in the Age of Black Lives which is designed to help individuals, families, and Matter. Writing for The Atlantic, Clint Smith communities talk about racism, racial identity and examines how having children has pushed him the way these forces shape society to re-evaluate his place in the Black Lives Matter movement: “Our children have raised the stakes of Antiracism Project ― The Project offers participants this fight, while also shifting the calculus of how we ways to examine the crucial and persistent issue move within it” of racism Check in on Your Black Employees, Now by Tonya Russell ARTICLES 75 Things White People Can Do For Racial Justice First, Listen. -

Anti-Racism Resources

Anti-Racism Resources Prepared for and by: The First Church in Oberlin United Church of Christ Part I: Statements Why Black Lives Matter: Statement of the United Church of Christ Our faith's teachings tell us that each person is created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27) and therefore has intrinsic worth and value. So why when Jesus proclaimed good news to the poor, release to the jailed, sight to the blind, and freedom to the oppressed (Luke 4:16-19) did he not mention the rich, the prison-owners, the sighted and the oppressors? What conclusion are we to draw from this? Doesn't Jesus care about all lives? Black lives matter. This is an obvious truth in light of God's love for all God's children. But this has not been the experience for many in the U.S. In recent years, young black males were 21 times more likely to be shot dead by police than their white counterparts. Black women in crisis are often met with deadly force. Transgender people of color face greatly elevated negative outcomes in every area of life. When Black lives are systemically devalued by society, our outrage justifiably insists that attention be focused on Black lives. When a church claims boldly "Black Lives Matter" at this moment, it chooses to show up intentionally against all given societal values of supremacy and superiority or common-sense complacency. By insisting on the intrinsic worth of all human beings, Jesus models for us how God loves justly, and how his disciples can love publicly in a world of inequality. -

Undercurrent (Blue Note)

Kenny Drew Undercurrent (Blue Note) Undercurrent Freddie Hubbard, trumpet; Hank Mobley, tenor sax; Kenny Drew, piano; Sam Jones, bass; Louis Hayes, drums. 1. Undercurrent (Kenny Drew) 7:16 Produced by ALFRED LION 2. Funk-Cosity (Kenny Drew) 8:25 Cover Photo by FRANCIS WOLFF 3. Lion's Den (Kenny Drew) 4:53 Cover Design by REID MILES 4. The Pot's On (Kenny Drew) 6:05 Recording by RUDY VAN GELDER 5. Groovin' The Blues (Kenny Drew) 6:19 Recorded on December 11, 1960, 6. Ballade (Kenny Drew) 5:29 Englewood Cliffs, NJ. The quintet that plays Kenny Drew's music here had never worked as a unit before the recording but the tremendous cohesion and spirit far outdistances many of today's permanent groups in the same genre. Of course, Sam Jones and Louis Hayes have been section mates in Cannonball Adderley's quintet since 1959 and this explains their hand-in- glove performance. With Drew, they combine to form a rhythm trio of unwavering beat and great strength. The two hornmen are on an inspired level throughout. Hank Mobley has developed into one of our most individual and compelling tenor saxophonists. His sound, big and virile, seems to assert his new confidence with every note. Mobley has crystallized his own style, mixing continuity of ideas, a fine sense of time and passion into a totality that grabs the listener and holds him from the opening phrase. Freddie Hubbard is a youngster but his accomplished playing makes it impossible to judge him solely from the standpoint of newcomer. This is not to say that he is not going to grow even further as a musician but that he has already reached a level of performance that takes some cats five more years to reach. -

Album Covers Through Jazz

SantiagoAlbum LaRochelle Covers Through Jazz Album covers are an essential part to music as nowadays almost any project or single alike will be accompanied by album artwork or some form of artistic direction. This is the reality we live with in today’s digital age but in the age of vinyl this artwork held even more power as the consumer would not only own a physical copy of the music but a 12’’ x 12’’ print of the artwork as well. In the 40’s vinyl was sold in brown paper sleeves with the artists’ name printed in black type. The implementation of artwork on these vinyl encasings coincided with years of progress to be made in the genre as a whole, creating a marriage between the two mediums that is visible in the fact that many of the most acclaimed jazz albums are considered to have the greatest album covers visually as well. One is not responsible for the other but rather, they each amplify and highlight each other, both aspects playing a role in the artistic, musical, and historical success of the album. From Capitol Records’ first artistic director, Alex Steinweiss, and his predecessor S. Neil Fujita, to all artists to be recruited by Blue Note Records’ founder, Alfred Lion, these artists laid the groundwork for the role art plays in music today. Time Out Sadamitsu "S. Neil" Fujita Recorded June 1959 Columbia Records Born in Hawaii to japanese immigrants, Fujita began studying art Dave Brubeck- piano Paul Desmond- alto sax at an early age through his boarding school. -

Black Lives Matter Booklist 2020

Black Lives Matter Booklist Here are the books from our Black Lives Matter recommendation video along with further recommendations from RPL staff. Many of these books are available on Hoopla or Libby. For more recommendations or help with Libby, Hoopla, or Kanopy, please email: [email protected] Picture Books A is for Activist, by Innosanto Nagara The Undefeated, by Kwame Alexander & Kadir Nelson Hands Up! by Breanna J. McDanie & Shane W. Evans I, Too, Am America, by Langston Hughes & Bryan Collier The Breaking News, by Sarah Lynne Reul Hey Black Child, by Useni Eugene Perkins & Bryan Collier Come with Me, by Holly M. McGhee & Pascal Lemaitre Middle Grade A Good Kind of Trouble, by Lisa Moore Ramee New Kid, Jerry Craft The Only Black Girls in Town, Brandy Colbert Blended, Sharon M. Draper Ghost Boys, Jewell Parker Rhodes Teen Non-Fiction Say Her Name, by Zetto Elliott & Loveiswise Twelve Days in May, by Larry Dane Brimner Stamped, by Jason Reynolds & Ibram X. Kendi Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates This Book is Anti-Racist, by Tiffany Jewell & Aurelia Durand Teen Fiction Dear Martin, by Nic Stone All American Boys, by Jason Reynolds & Brendan Kiely Light it Up, by Kekla Magoon Tyler Johnson was Here, by Jay Coles I Am Alfonso Jones, by Tony Medina, Stacey Robinson & John Jennings Black Enough, edited by Ibi Zoboi I'm Not Dying with You Tonight, by Kimberly Jones & Gilly Segal Adult Memoirs All Boys Aren't Blue, by George M. Johnson When They Call You a Terrorist, by Patrisse Khan-Cullors & Asha Bandele Eloquent Rage, by Brittney Cooper I'm Still Here, Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness, by Austin Channing Brown How We Fight for Our Lives, by Saeed Jones Cuz, Danielle Allen This Will Be My Undoing, by Morgan Jerkins Adult Nonfiction Tears We Cannot Stop, by Michael Eric Dyson So You Want to Talk About Race, by Ijeoma Oluo White Fragility, by Robin Diangelo How To Be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Selected Sermons by Sam Jones During His Emergence As a National Figure, 1872-1885

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1980 A Rhetorical Analysis of Selected Sermons by Sam Jones During His Emergence as a National Figure, 1872-1885. Herman Daniel Champion Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Champion, Herman Daniel Jr, "A Rhetorical Analysis of Selected Sermons by Sam Jones During His Emergence as a National Figure, 1872-1885." (1980). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3553. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3553 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. -

The Recordings

Appendix: The Recordings These are the URLs of the original locations where I found the recordings used in this book. Those without a URL came from a cassette tape, LP or CD in my personal collection, or from now-defunct YouTube or Grooveshark web pages. I had many of the other recordings in my collection already, but searched for online sources to allow the reader to hear what I heard when writing the book. Naturally, these posted “videos” will disappear over time, although most of them then re- appear six months or a year later with a new URL. If you can’t find an alternate location, send me an e-mail and let me know. In the meantime, I have provided low-level mp3 files of the tracks that are not available or that I have modified in pitch or speed in private listening vaults where they can be heard. This way, the entire book can be verified by listening to the same re- cordings and works that I heard. For locations of these private sound vaults, please e-mail me and I will send you the links. They are not to be shared or downloaded, and the selections therein are only identified by their numbers from the complete list given below. Chapter I: 0001. Maple Leaf Rag (Joplin)/Scott Joplin, piano roll (1916) listen at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9E5iehuiYdQ 0002. Charleston Rag (a.k.a. Echoes of Africa)(Blake)/Eubie Blake, piano (1969) listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7oQfRGUOnU 0003. Stars and Stripes Forever (John Philip Sousa, arr. -

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION the Medicine Bundles of Ihe Florida Seminole and the Green Corn Dance

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 151 Anthropological Papers, No. 35 The Medicine Bundles of ihe Florida Seminole and the Green Corn Dance By LOUIS CAPRON 155 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 159 The Florida Seminole 160 Mode of living 161 The Medicine Bundles 162 The Medicine 163 The Rattlesnake and the Horned Owl 164 How the Medicine came (Cow Creek version) 165 How the Medicine came (Miccosuki version) 166 African animals 166 One original Bundle 167 The horn of the Snake King 168 Power in War Medicine 168 The Boss Stone 169 War rattles.- 170 How the Medicine is kept 171 New Medicine 171 Other Medicine 172 Religion 172 The Green Corn Dance 175 The dance ground 182 Helpers with the Medicine 183 Tin-can rattles 184 The dances. 186 Picnic Day 188 Court Day 188 The Medicine Bundle 190 Scratching the boys 191 The Feather Dance 193 The Black Drinks 195 Crime and the Court 196 State of the nation 198 Court Day afternoon 198 The last nightl 200 The Big Pot Drink 202 Dance all night 202 The scene at midnight 204 The final morning 205 The scratching 206 Explanation of plates 208 157 158 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY [Bulu 151J ILLUSTRATIONS PLATES PAGE 7. Typical Seminole village 210 8. Two Seminole Medicine Men. Left: Ingraham Billy, Medicine Man of the Tamiami Trail Seminole. Right: Sam Jones, long-time Medicine Man of the Cow Creek Seminole 210 9. Two Seminole Medicine Men. Left: John Osceola, Big Cypress Medi- cine Man at the 1949 Green Corn Dance. Right: Josie Billy, former Medicine Man of the Tamiami Trail Seminole 210 10. -

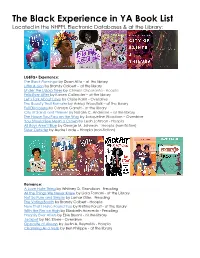

The Black Experience in YA Book List Located in the NHFPL Electronic Databases & at the Library

The Black Experience in YA Book List Located in the NHFPL Electronic Databases & at the Library: LGBTQ+ Experience: The Black Flamingo by Dean Atta – at the library Little & Lion by Brandy Colbert – at the library Under the Udala Trees by Chinelo Okparanta - Hoopla Felix Ever After by Kacen Callender – at the library Let’s Talk About Love by Claire Kann - Overdrive The Beauty That Remains by Ashley Woodfolk – at the library Full Disclosure by Camryn Garrett - at the library City of Saints and Thieves by Natalie C. Anderson – at the library The House You Pass on the Way by Jacqueline Woodson – Overdrive You Should See Me In a Crown by Leah Johnson - Hoopla All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson – Hoopla (non-fiction) Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde – Hoopla (non-fiction) Romance: A Love Hate Thing by Whitney D. Grandison - Freading All the Things We Never Knew by Liara Tamani - at the Library Not So Pure and Simple by Lamar Giles - Freading The Voting Booth by Brandy Colbert - Hoopla Now That I Have Found You by Kristina Forest - at the library With the Fire on High by Elizabeth Acevedo - Freading Happily Ever Afters by Elsie Bryant - at the library Jackpot by Nic Stone - Overdrive Opposite of Always by Justin A. Reynolds - Hoopla Charming As a Verb by Ben Philippe - at the library Fantasy & Sci-Fi: Pet by Akwaeke Emezi – at the library (LGBTQ+) Dread Nation by Justina Ireland - Freading (LGBTQ+) An Unkindness of Ghosts by Rivers Solomon - Hoopla (LGBTQ+) American Street by Ibi Zoboi – Freading A Song Below Water by Bethany C. -

DEAR MARTIN and DEAR JUSTYCE Photo © Nigel Livingstone

CLASSROOM UNIT FOR DEAR MARTIN AND DEAR JUSTYCE Photo © Nigel Livingstone RHTeachersLibrarians.com @RHCBEducators TheRandomSchoolHouse Justyce McAllister is top of his class and set for the Ivy League— but none of that matters to the police officer who just put him in handcuffs. And despite leaving his rough neighborhood behind, he can’t escape the scorn of his former peers or the ridicule of his new classmates. Justyce looks to the teachings of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. for answers. But do they hold up anymore? He starts a journal to Dr. King to find out. Then comes the day Justyce goes driving with his best friend, Manny, windows rolled down, music turned up— way up—sparking the fury of a white off-duty cop beside them. Words fly. Shots are fired. Justyce and Manny are caught in the crosshairs. In the media fallout, it’s Justyce who is under attack. Vernell LaQuan Banks and Justyce McAllister grew up a block apart in the southwest Atlanta neighborhood of Wynwood Heights. Years later, though, Justyce walks the illustrious halls of Yale University . and Quan sits behind bars at the Fulton Regional Youth Detention Center. Through a series of flashbacks, vignettes, and letters to Justyce—the protagonist of Dear Martin—Quan’s story takes form. Troubles at home and misunderstandings at school give rise to police encounters and tough decisions. But then there’s a dead cop and a weapon with Quan’s prints on it. What leads a bright kid down a road to a murder charge? Not even Quan is sure. -

A Reading List for Adults, Teens, and Youth

A READING LIST FOR ADULTS, TEENS, AND YOUTH. ADULTS Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Penguin Random House Publisher In a profound work that pivots from the biggest questions about American history and ideals to the most intimate concerns of a father for his son, Ta-Nehisi Coates offers a powerful new framework for understanding our nation’s history and current crisis. Americans have built an empire on the idea of “race,” a falsehood that damages us all but falls most heavily on the bodies of black women and men—bodies exploited through slavery and segregation, and, today, threatened, locked up, and murdered out of all proportion. What is it like to inhabit a black body and find a way to live within it? And how can we all honestly reckon with this fraught history and free ourselves from its burden? Stamped From the Beginning by Ibram X. Kendi, Bold Type Books Some Americans insist that we're living in a post-racial society. But racist thought is not just alive and well in America--it is more sophisticated and more insidious than ever. And as award-winning historian Ibram X. Kendi argues, racist ideas have a long and lingering history, one in which nearly every great American thinker is complicit. How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi, One World Publisher Antiracism is a transformative concept that reorients and reenergizes the conversation about racism—and, even more fundamentally, points us toward liberating new ways of thinking about ourselves and each other. At its core, racism is a powerful system that creates false hierarchies of human value; its warped logic extends beyond race, from the way we regard people of different ethnicities or skin colors to the way we treat people of different sexes, gender identities, and body types.