Dinton Roll of Honour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SS Hazelwood First World War Site Report

Forgotten Wrecks of the SS Hazelwood First World War Site Report 2018 Maritime Archaeology Trust: Forgotten Wrecks of the First World War Site Report SS Hazelwood (2018) FORGOTTEN WRECKS OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR SS HAZELWOOD SITE REPORT Page 1 of 16 Maritime Archaeology Trust: Forgotten Wrecks of the First World War Site Report SS Hazelwood (2018) Table of Contents i Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................ 2 ii Copyright Statement ........................................................................................................................ 3 iii List of Figures .................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Project Background ............................................................................................................................ 3 2. Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Desk Based Historic Research ....................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Associated Artefacts ..................................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Site Visit/Fieldwork ....................................................................................................................... 5 3. Vessel Biography: -

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible. -

Medway Heritage Asset Review 2017 Final Draft: November 2017

Medway Heritage Asset Review 2017 Final Draft: November 2017 Executive Summary The Medway Heritage Asset Review intends to provide a comprehensive overview of the heritage assets in Medway in order to inform the development of a Heritage Strategy to support the emerging Medway Local Plan 2015. Medway benefits from a rich heritage spanning millennia, underpinning the local distinctiveness and creating a unique and special character that can be readily interpreted through the historic environment. The main report is broken down into sections, initially looking at the topography of Medway and how this influenced human settlement in the area, then looking at the development of the key settlements in Medway; taking into consideration the key drivers for their establishment and identifying existing heritage assets. Furthermore, the main influences to development in the area are also considered; including Chatham Dockyard and the military, the brick, cement and lime industry, agriculture, maritime and religion. Through investigating Medway’s history both geographically and thematically, the significance of heritage assets and the importance of historic landscapes can be readily identified; enabling a better understanding and providing opportunities to enhance their enjoyment. Non-designated heritage assets are also identified using a broad range of sources; providing a deeper knowledge of what shapes the distinct local character experienced in Medway and the how this identity is of great importance to the local community. The report concludes with suggestions for additional areas of research and identifies themes to be considered to inform the development of a coherent and robust Heritage Strategy that will help enhance, understand and celebrate Medway’s heritage for years to come. -

Amble Remembers the First World War

AMBLE REMEMBERS THE FIRST WORLD WAR WRITTEN AND COMPILED BY HELEN LEWIS ON BEHALF OF AMBLE TOWN COUNCIL The assistance of the following is gratefully acknowledged: Descendants of the Individuals Amble Social History Group The Northumberland Gazette The Morpeth Herald Ancestry Commonwealth War Graves Commission Soldiers Died in the Great War Woodhorn Museum Archives Jane Dargue, Amble Town Council In addition, the help from the local churches, organisations and individuals whose contributions were gratefully received and without whom this book would not have been possible. No responsibility is accepted for any inaccuracies as every attempt has been made to verify the details using the above sources as at September 2019. If you have any accurate personal information concerning those listed, especially where no or few details are recorded, or information on any person from the area covered, please contact Amble Town Council on: 01665 714695 or email: [email protected] 1 Contents: What is a War Memorial? ......................................................................................... 3 Amble Clock Tower Memorial ................................................................................... 5 Preservation and Restoration ................................................................................. 15 Radcliffe Memorial .................................................................................................. 19 Peace Memorial ...................................................................................................... -

Bravereport Issue 41 Banbridge

Issue 40 Page 1! Brave Report ! HMS Richmond under Banbridge command BANBRIDGE AND GILFORD’S NAVAL RECORD In May 2014 when HMS Richmond docked at Belfast Harbour, the Banbridge tradition of service in the Royal Navy was once more Northern Ireland - Service in the Royal Navy - In Remembrance Issue 40 Page 2! expressed. Lieutenant Commander Mark Anderson, a Banbridge native, was in command of was the Type 23 frigate. Portsmouth based she had recently returned to the UK from deployment to the Atlantic Patrol Tasking where her passage included stops in Cape Verde, Ascension and South Georgia. ! Lt Cdr Mark Anderson - also commanded HMS Mersey, one of three River class offshore patrol vessels whose primary role is to protect fish stocks Banbridge town’s tradition of naval service is unavoidable in its public architecture. The Crozier monument highlights the cost of polar exploration which was predominantly led by the Royal Navy in the quest for alternative sea routes. The cost Northern Ireland - Service in the Royal Navy - In Remembrance Issue 40 Page 3! born by individuals and families is well illustrated by the inscription on the monument. It reads - To perpetuate the remembrance of talent, enterprise, and worth as combined in the character and evidenced in the life of Captain Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier R.N. F.R.S. this monument has been erected by friends, who, as they valued him in life,regret him in death. He was second in command with Captain Sir John Franklin R.N. F.R.S., and captain of H.M. ship Terror, in the polar expedition which left England on the 22 May 1845. -

Remni May 31

MAY 31 remembrance ni HMS Defence and HMS Warrior passing the battlecruiser squadron at the Battle of Jutland Battle of Jutland The battle which took place off Denmark’s Jutland peninsula was the largest naval battle of the war and it was definitive in terms of naval engagement for the remainder of the hostilities. The Battle of Jutland was the only time that the British and German fleets of 'dreadnought' battleships actually came to blows. It was a confused and bloody action involving 250 ships and Page 1 MAY 31 around 100,000 men. It saw the greatest ever exchange of naval gunfire. The battle resulted in the loss of HM ships Queen Mary, Indefatigable, Invincible, Defence, Black Prince, Warrior, and of HM TBD 's Tipperary, Ardent, Fortune, Shark, Sparrowhawk, Nestor, Nomad, and Turbulent. Commander Edward Bingham from Northern Ireland was awarded the Victoria Cross for his leadership. The Flag Captain of HMS Iron Duke at Battle of Jutland, was Frederick Dryer from Armagh. Over eighty men from Northern Ireland were amongst the casualties. The German navy sought to engage the Royal Navy with a view to weakening it so that in any later engagements the balance of power would be more in its favour. The German commander, Admiral Scheer, planned to attack British merchant shipping to Norway, expecting to lure out both Admiral Beatty’s Battlecruiser Force and Admiral Jellicoe's Grand Fleet, further away at Scapa Flow. Scheer hoped to destroy Beatty before Jellicoe arrived On May 30th 1916, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, Commander in Chief of the Grand Fleet, in accord with the general policy of periodic sweeps through the North Sea ordered the ships of the fleet to leave their bases. -

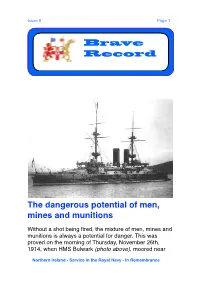

Brave Record Issue 8

Issue 8 Page !1 Brave Record ! The dangerous potential of men, mines and munitions Without a shot being fired, the mixture of men, mines and munitions is always a potential for danger. This was proved on the morning of Thursday, November 26th, 1914, when HMS Bulwark (photo above), moored near Northern Ireland - Service in the Royal Navy - In Remembrance Issue 8 Page !2 Sheerness, was torn apart with an internal explosion and sank. At least three men from Northern Ireland died. A similar incident occurred on HMS Princess Irene the following May in which at least eight men from Northern Ireland were killed. HMS Bulwark HMS Bulwark, a battleship of 15,000 tons, was moored to No.17 buoy in Kethole Reach on the River Medway, almost opposite the town of Sheerness, Isle of Sheppey, Kent. It was one of the ships forming the 5th Battle Squadron. She had been moored there for some days, and many of her crew had been given leave the previous day. They had returned to the Bulwark at 7 o'clock that morning and the full complement was onboard. The usual ship's routine was taking place. Officers and men were having breakfast in the mess below deck, other were going about their normal duties. A band was practising while some men were engaged in drill. The disaster struck. A roaring and rumbling sound was heard and a huge sheet of flame and debris shot up. The ship lifted out of the water and fell back. There was a thick cloud of grey smoke and further explosions. -

War Medals, Orders and Decorations

War Medals, Orders and Decorations To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Day of Sale: Thursday 28 June 2018 at 2.00pm Public viewing: Nash House, St George Street, London W1S 2FQ Monday 25 June 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 26 June 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 27 June by appointment Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 94 Price £15 Enquiries: David Kirk or James Morton Cover illustrations: Lot 615 (front); lot 628 (back); lot 627 (inside front); lot 536 (inside back) Nash House, St George Street, London W1S 2FQ Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Online Bidding This auction can be viewed online at www.the-saleroom.com, www.numisbids.com and www.sixbid.com. Morton & Eden Ltd offers an online bidding service via www.the-saleroom.com. This is provided on the under- standing that Morton & Eden Ltd shall not be responsible for errors or failures to execute internet bids for reasons including but not limited to: i) a loss of internet connection by either party ii) a breakdown or other problems with the online bidding software iii) a breakdown or other problems with your computer, system or internet connection. -

Dover Patrol

DOVER PATROL (Trawlers & Minesweepers) Civic War Memorial This important local civic war memorial was placed inside the Holy Trinity Church, Dover in November 1918 by the families of the fallen men of the Dover Patrol (Trawlers & Minesweeping Patrol). In 1945 the church was sadly demolished after enemy bomb damage. The memorial needed a new home. The Dover Sea Cadets (Training Ship Lynx) at Archcliffe Fort agreed to look after it at their headquarters. The Sea Cadets moved from Archcliffe Fort in the 1970’s and the memorial was given to Dover District Council for safekeeping. The memorial is presently held in safekeeping by the Dover Museum. In 2006 it was being stored in an obscure shed at Deal. It is hoped that the memorial will be placed on public display at some stage in the future… The Great War 1914 – 1919 LEGEND + DIED IN SERVICE Roll of Honour LEFT HAND LEAF Sub Lieutenant J.H RIDDING + Petty Officer A FIELDER + Sub Lieutenant D BROWN + Petty Officer F ALLEN + Wireless Telegraph Operator E.A SUTTON Seaman F RANDALL + + Lieutenant W.H MERTON Deck Hand J.N LAMBIE + Sub-Lieutenant F.R WINPENNY + 2nd Engineer W SHELLEY + Lieutenant Commander H CALDER + Steward G SMITH + Assistant Engineer F.W PENDER + Cook W MOORE + Sub Lieutenant J.A MACINTOSH + Assistant Steward G MAJOR + Skipper J SANDFORD + Signal Boy A.W MANNING + Skipper R SAUNDERS + Trimmer W.H MOSS + Skipper G WEST + Fireman Trimmer A.S MOTT Skipper G.A ROSE + Fireman Trimmer K AYLES + Skipper I PEARCE + Greaser E PRITCHARD + Skipper T KAY + Able Seaman H CARLING + Lieutenant -

World War Two Memorial the Following Pages Commemorate the Men from Faringdon Who Died in the Second World War

Faringdon World War Two Memorial The following pages commemorate the men from Faringdon who died in the Second World War. In addition to the 34 listed on the Faringdon War Memorial, these pages include those who are buried in All Saints’ Churchyard (Habgood, Harrison, Morbey and Tarr) and in the Nonconformist Cemetery on Canada Lane (Heron) who are not named on the Faringdon War Memorial. There is also a tribute to Anthony Pepall, Jack Bryan’s friend, who was killed on the retreat to Dunkirk. The information has been compiled from data obtained from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission web site and other records. If you can add any further details, please contact me or Faringdon Town Council. Dr M L H Wise: Tel: 01367 240597 Faringdon Town Council: Tel: 01367 240281 In Memory of Able Seaman ROYCE LEONARD BAILEY P/JX 519294, H.M.S. Isis, Royal Navy who died, age 19, on 20 July 1944 Son of Leonard and Lilian Bailey, of Faringdon, Berkshire. Remembered with honour Faringdon War Memorial and PORTSMOUTH NAVAL MEMORIAL Commemorated in perpetuity by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission Standing on Southsea Common overlooking the promenade in Portsmouth, Hampshire, is the Portsmouth Naval Memorial. It commemorates nearly 10,000 naval personnel of the First World War and almost 15,000 of the Second World War who were lost or buried at sea. (See next page for the history of HMS Isis.) HMS Isis (D87), named for the Egyptian goddess, was an I-class destroyer laid down by the Yarrow and Company, at Scotstoun in Glasgow on 6 February 1936, launched on 12 November 1936 and commissioned on 2 June 1937. -

R.N.D. Royal Naval Division

Ttle IN®eX. Albert John Walls of the Hood Battalion. Copyright © Leonard Sellers, 1999. ISSN. 1368-499X. Albert John Walls. If it was not formy Great Uncle, Albert John Walls, I would not have researched and my firstbook 'The Hood Battalion' would not have been published. This furtherignited my interest, leading eventually, to the publication of the of the R.N.D. In his memory, I set out below his service record. Albert John Walls was born on the 261h June 1878 at Peckham, London. Prior to entering the Navy, he was employed as a printer. Albert joined the service on the 281h October 1903, for a period of 5 years, to be followed by 7 years in the Reserves. Described as a man of five feet, seven and a half inches, thirty six inch chest, with dark completion, hair and eyes. He was allocated an official service number of Chatham B 5397 with a rating of Stoker 2nct class. SS100111. SHIPSAND SHORE ESTABLISHMENTS ON WHICH HE SERVED :- HMS Northumberland. Chatham 28/10/03 -31/12/03 HMS A cheron. Armoured Cruiser 01/01 /04 -07/06/04 HMS Pembroke Chatham 08/06/04 -20/06/04 HMS Illustrious Battleship 21/06/04 - 14/09/05 HMS Pembroke Chatham 15/09/05 -04/12/05 HMS Leviathan Armoured Cruiser 05/12/05 - 26/11/06 Promoted Stoker 1 st Class. HMS Bacchante Armoured Cruiser 27/11/06 -17/02/08 HMS Pemhrokc Chatham 18/02/08 - 24/06/08 HMS Agamemnon Battleship 25/06/08 - 16/l 0/08 HMS Pembroke Chatham 17/10/08 -06/11/08 Discharged on the 6th November 1908 as his service had expired, at Chatham he transferred to the Royal Fleet Reserve the following day. -

Hms Boadicea (H 65)

HMS BOADICEA (H 65) LISTE DES VICTIMES 1. ABBEY, SAMUEL (18), Ordinary Seaman (no. C/JX 648840), HMS Boadicea, Royal Navy, †13/06/1944, Son of James and Phoebe Jane Abbey, of Rounds Green, Oldbury, Worcestershire, Memorial: Portland Royal Naval Cemetery 2. ABBOTT, ERIC (19), Stoker 1st Class (no. C/KX 595708), HMS Boadicea, Royal Navy, †13/06/1944, Son of Thomas and Mary Abbott, of Upholland, Lancashire, Memorial: Chatham Naval Memorial 3. ALDRIDGE, JOSEPH ALBERT , Petty Officer Cook (S) (no. C/MX.56877), HMS Boadicea, Royal Navy, †13/06/1944, Memorial: Chatham Naval Memorial 4. APLIN, WALTER SWAN (25), Able Seaman (no. C/JX 206070), HMS Boadicea, Royal Navy, †13/06/1944, Son of Walter Holt Aplin and Ethel Vipond Aplin, of Cullercoats, Northumberland, Memorial: Chatham Naval Memorial 5. AVERLEY, ROLAND EDWARD (27), Petty Officer (no. C/JX 171380), Mentioned in Despatches, HMS Boadicea, Royal Navy, †13/06/1944, Son of Edward and Louisa Martha Averley; husband of Mildred Averley, of Gillingham, Kent. Royal Humane Society's Certificate, Memorial: Chatham Naval Memorial 6. AYRES, WILLIAM STANLEY (22), Signalman (no. C/JX 270008), HMS Boadicea, Royal Navy, †13/06/1944, Son of Ernest and Matilda M. Ayres, of Manchester, Memorial: Chatham Naval Memorial 7. BABB, HENRY JOHN (36), Assistant Steward (no. C/LX 623694), HMS Boadicea, Royal Navy, †13/06/1944, Son of Charles and Susan Babb; husband of Alice Elsabeth Babb, of Islington, London, Memorial: Chatham Naval Memorial 8. BAILEY, BASIL , Petty Officer Supply (no. C/MX 69370), HMS Boadicea, Royal Navy, †13/06/1944, Memorial: Chatham Naval Memorial 9.