Jeff P. Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

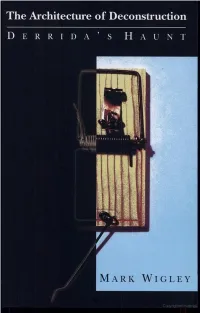

The Architecture of Deconstruction: Derrida's Haunt

The Architecture o f Deconstruction: Derrida’s Haunt Mark Wigley The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Fifth printing, 1997 First M IT Press paperback edition, 1995 © 1993 M IT Press Ml rights reserved. No part o f this book may be reproduced in any form by any elec tronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information stor age and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was printed and bound in the United States o f America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wigley, Mark. The architecture of deconstruction : Derrida’s haunt / Mark Wigley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-23170-0 (H B ), 0-262-73114-2 (PB) 1. Deconstruction (Architecture) 2. Derrida, Jacques—Philosophy. I. T itle . NA682.D43W54 1993 720'. 1—dc20 93-10352 CIP For Beatriz and Andrea Any house is a fa r too com plicated, clumsy, fussy, mechanical counter feit of the human body . The whole interior is a kind of stomach that attempts to digest objects . The whole life o f the average house, it seems, is a sort of indigestion. A body in ill repair, suffering indispo sition—constant tinkering and doctoring to keep it alive. It is a marvel, we its infesters, do not go insane in it and with it. Perhaps it is a form of insanity we have to put in it. Lucky we are able to get something else out of it, thought we do seldom get out of it alive ourselves. —Frank Lloyd Wright ‘The Cardboard House,” 1931. -

1 Poems About Eagles This Is a Collection of Poems

Poems About Eagles This is a collection of poems - old and new - that have been written about eagles. Some you may recognize because they are included in anthologies. Others are from “Kindred Spirits” whose musings about eagles lead them to put pen to paper. Some have been sent to us to share, and we are happy to do so here. If you have a poem you’d like to share about eagles, please email [email protected]. The Dalliance of Eagles by Walt Whitman Skirting the river road, (my forenoon walk, my rest,) Skyward in air a sudden muffled sound, the dalliance of the eagles, The rushing amorous contact high in space together, The clinching interlocking claws, a living, fierce, gyrating wheel, Four beating wings, two beaks, a swirling mass tight grappling, In tumbling turning clustering loops, straight downward falling, Till o’er the river pois’d, the twain yet one, a moment’s lull, A motionless still balance in the air, then parting, talons loosing, Upward again on slow-firm pinions slanting, their separate diverse flight, She hers, he his, pursuing. f The Eagle Isaiah 40:31 by Edwin Curran KJV The dome of heaven is thy house But they that wait upon the LORD shall renew their Bird of the mighty wing, strength; they shall mount up with wings as eagles; they The silver stars are as thy boughs shall run, and not be weary; and they shall walk, and not Around thee circling. faint. f Thy perch is on the eaves of heaven Thy white throne all the skies Thou art like lightning driven Flashing over paradise! f 1 The Eagle by Isaac McLellan (1806-1899) Monarch of the realms supernal, Thou wingest where a tropic sky Ranger of the land and sea, Bendeth its celestial dome, Symbol of the Grand Republic, Where sparkling waters greet the eye, Who so noble and so free? And gentlest breezes fan the foam; Thine the boundless fields of either, Where spicy breath from groves of palm, Heaven’s unfathom’d depths are thine; Laden with aromatic balm, Far beyond our human vision, Blows ever, mingled with perfume On thy vans the sunbeams shine. -

The Chronicle

I I N N L L V V A A I I U U T T T T A A I I T T R R I I I I O P O P S S N N A L A L L A L A N N R R E IO E IO L S L S AT IS AT IS IONAL M IONAL M Highlands Ranch, Colorado The Chronicle ST. LUKE’S UNITED METHODIST CHURCH JUNE/JULY 2014 I I N N L L V A V A I I U Inside This Issue:U T T T T A A I From Rev. Sallie.................3I T T R R I I I I O P SpiritualO Engagement.......5P S S N Golf! N A L Children’sA Ministry..........6L L A L A Golfer, Sponsor and N N R UMW R Update..................7 E IO E IO Volunteer signups have L S L S A IS A S T M T I IONAL Music & DramaIONA .................9L M begun for our 11th Annual SLY................................10 Golf Event August 2nd! We’ll be Graduates.....................11 playing again at Murphy Creek Golf Course with a 8:00am tee-off. The Seasoned Voyagers........12 tournament supports our church bus that is used for Windcrest rides and much more! each Sunday, youth mission trips, retreats and much more. Register at I I N N L L V V A A the Golf Event table or on line at www.stlukeshr/golf by July 20, 2014. I I U U T T T T A A I I T T R R I I I I O P O P FROM REV. -

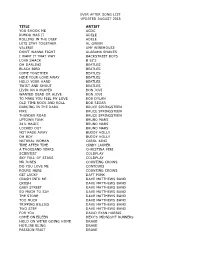

Ever After Song List August 2018

EVER AFTER SONG LIST UPDATED AUGUST 2018 TITLE ARTIST YOU SHOOK ME ACDC RUMOR HAS IT ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP ADELE LETS STAY TOGETHER AL GREEN VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE DON'T WANNA FIGHT ALABAMA SHAKES I WANT IT THAT WAY BACKSTREET BOYS LOVE SHACK B 52'S OH DARLING BEATLES BLACK BIRD BEATLES COME TOGETHER BEATLES HIDE YOUR LOVE AWAY BEATLES HOLD YOUR HAND BEATLES TWIST AND SHOUT BEATLES LIVIN ON A PRAYER BON JOVI WANTED DEAD OR ALIVE BON JOVI TO MAKE YOU FEEL MY LOVE BOB DYLAN OLD TIME ROCK AND ROLL BOB SEGAR DANCING IN THE DARK BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN FIRE BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN THUNDER ROAD BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN UPTOWN FUNK BRUNO MARS 24 k MAGIC BRUNO MARS LOCKED OUT BRUNO MARS NOT FADE AWAY BUDDY HOLLY OH BOY BUDDY HOLLY NATURAL WOMAN CAROL KING TIME AFTER TIME CINDY LAUPER A THOUSAND YEARS CHRISTINA PERI SCIENTIST COLDPLAY SKY FULL OF STARS COLDPLAY MR JONES COUNTING CROWS DO YOU LOVE ME CONTOURS ROUND HERE COUNTING CROWS GET LUCKY DAFT PUNK CRASH INTO ME DAVE MATTHEWS BAND CRUSH DAVE MATTHEWS BAND GREY STREET DAVE MATTHEWS BAND SO MUCH TO SAY DAVE MATTHEWS BAND THE STONE DAVE MATTHEWS BAND TOO MUCH DAVE MATTHEWS BAND TRIPPING BILLIES DAVE MATTHEWS BAND TWO STEP DAVE MATTHEWS BAND FOR YOU DAVID RYAN HARRIS COME ON EILEEN DEXY'S MIDNIGHT RUNNERS HOLD ON WE'RE GOING HOME DRAKE HOTLINE BLING DRAKE PASSION FRUIT DRAKE EVER AFTER SONG LIST UPDATED AUGUST 2018 SAVE TONIGHT EAGLE EYE CHERRY SEPTEMBER EARTH WIND AND FIRE PERFECT ED SHEERAN CASTLE ON THE HILL ED SHEERAN PHOTOGRAPH ED SHEERAN SHAPE OF YOU ED SHEERAN THINKING OUT LOUD ED SHEERAN EX'S AND OH'S -

Total Tracks Number: 1108 Total Tracks Length: 76:17:23 Total Tracks Size: 6.7 GB

Total tracks number: 1108 Total tracks length: 76:17:23 Total tracks size: 6.7 GB # Artist Title Length 01 00:00 02 2 Skinnee J's Riot Nrrrd 03:57 03 311 All Mixed Up 03:00 04 311 Amber 03:28 05 311 Beautiful Disaster 04:01 06 311 Come Original 03:42 07 311 Do You Right 04:17 08 311 Don't Stay Home 02:43 09 311 Down 02:52 10 311 Flowing 03:13 11 311 Transistor 03:02 12 311 You Wouldnt Believe 03:40 13 A New Found Glory Hit Or Miss 03:24 14 A Perfect Circle 3 Libras 03:35 15 A Perfect Circle Judith 04:03 16 A Perfect Circle The Hollow 02:55 17 AC/DC Back In Black 04:15 18 AC/DC What Do You Do for Money Honey 03:35 19 Acdc Back In Black 04:14 20 Acdc Highway To Hell 03:27 21 Acdc You Shook Me All Night Long 03:31 22 Adema Giving In 04:34 23 Adema The Way You Like It 03:39 24 Aerosmith Cryin' 05:08 25 Aerosmith Sweet Emotion 05:08 26 Aerosmith Walk This Way 03:39 27 Afi Days Of The Phoenix 03:27 28 Afroman Because I Got High 05:10 29 Alanis Morissette Ironic 03:49 30 Alanis Morissette You Learn 03:55 31 Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know 04:09 32 Alaniss Morrisete Hand In My Pocket 03:41 33 Alice Cooper School's Out 03:30 34 Alice In Chains Again 04:04 35 Alice In Chains Angry Chair 04:47 36 Alice In Chains Don't Follow 04:21 37 Alice In Chains Down In A Hole 05:37 38 Alice In Chains Got Me Wrong 04:11 39 Alice In Chains Grind 04:44 40 Alice In Chains Heaven Beside You 05:27 41 Alice In Chains I Stay Away 04:14 42 Alice In Chains Man In The Box 04:46 43 Alice In Chains No Excuses 04:15 44 Alice In Chains Nutshell 04:19 45 Alice In Chains Over Now 07:03 46 Alice In Chains Rooster 06:15 47 Alice In Chains Sea Of Sorrow 05:49 48 Alice In Chains Them Bones 02:29 49 Alice in Chains Would? 03:28 50 Alice In Chains Would 03:26 51 Alien Ant Farm Movies 03:15 52 Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal 03:41 53 American Hifi Flavor Of The Week 03:12 54 Andrew W.K. -

Acoustic Events 2015 Copy 2.Pages

Dichtomy, LLC DJs Acoustic Events Some Devil: the music of Dave Matthews 936 Marguerite Drive Winston-Salem, NC 27106 336.602.3357 www.dichotomyllc.com Our mission to you… The aim of Dichotomy Entertainment is to provide the highest quality musical entertainment for any event in the greater Triad area. This idea was born from the need to incorporate the freelance entities of Joshua Moyer and DJ Dichotomy who -- strictly by word of mouth advertising, excellent customer service, and exemplary performances -- have built a strong foundation in the arts community of Winston-Salem over the past seven years. Primarily DJing weddings, private and corporate events; Joshua keeps an intensely full schedule. Coming from the club/ EDM style of DJing; he is known for his prowess on the microphone as an MC, smooth mixing & great energy and flow throughout your event. The recipient of the Forsyth County Entertainment Award for 2013 Rock/Pop Artist of the Year, Joshua was also nominated in categories for Best Male Musician and Best DJ. He performs at various venues in the Triad in the solo acoustic medium, always incorporating plenty of looping and improvisation into his sets. Mixing original music with a myriad of covers (including rock, blues, reggae, and singer/songwriter) is his specialty. Previous Performance Venues: 10-0-1 Artistika Azul Ultra Lounge Benton Convention Center Brewski’s Tavern Bridger Field House, WFU Bucked Up Super Saloon Burke Street Pub Castle McCullogh Cellar 4201 Club Therapy Crown Station (CLT) District Roof Top Bar & Grille Downtown Brody’s Fox & Hound Grassy Creek Vineyards Graylyn Conference Center Halo (CLT) Millenium Center Milton Rhodes Center for the Arts Mod Bar O. -

Quinn Hedges Song List 033018.Numbers

Song Ar'st Don't Follow Alice in Chains Got Me Wrong Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Ramblin Man Allman Brothers Band When You Say Nothing at All Allison Krauss Arms of a Woman Amos Lee Seen It All Before Amos Lee Keep it Loose, Keep it Tight Amos Lee What’s Been Going On Amos Lee Violin Amos Lee The Weight Band Up On Cripple Creek Band It Makes No Difference Band Here There and Everywhere Beatles Blackbird Beatles Till There Was You Beatles Golden Slumbers Beatles Here Comes The Sun Beatles While My Guitar Gently Weeps Beatles Across The Universe Beatles In My Life Beatles Something Beatles Yesterday Beatles Two of Us Beatles The Luckiest Ben Folds Army Ben Folds Fred Jones pt. 2 Ben Folds Brick Ben Folds Forever Ben Harper Another Lonely Day Ben Harper Burn One Down Ben Harper Not Fire Not Ice Ben Harper She's Always a Woman To Me Billy Joel Hard to Handle Black Crows Can't Find My Way Home Blind Faith Change Blind Melon No Rain Blind Melon Knocking on Heaven's Door Bob Dylan Tangled Up In Blue Bob Dylan You Aint' Goin Nowhere Bob Dylan I Shall Be Released Bob Dylan Stir it Up Bob Marley Flume Bon Iver The Way it Is Bruce Hornsby Streets of Philadelphia Bruce Springsteen Mexico Cake She Aint Me Carrie Rodriguez !1 Drive Cars Trouble Cat Stevens Wild World Cat Stevens Wicked Game Chris Isaak Yellow Coldplay Trouble Coldplay Don't Panic Coldplay Warning Sign Coldplay Sparks Coldplay Fix You Coldplay Green Eyes Coldplay The Scientist Coldplay Fix You Coldplay In My Place Coldplay Omaha Counting Crows A Long December Counting Crows -

BRYAN HANSEN Song List.Xlsx

BRYAN HANSEN WILLIAM BLAKEY SONG LIST JAN 2018 SONG NAME: ARTIST: LETS STAY TOGETHER AL GREEN DON'T WANNA FIGHT ALABAMA SHAKES I WANT IT THAT WAY BACKSTREET BOYS TWIST AND SHOUT BEATLES COME TOGETHER BEATLES IN MY LIFE BEATLES HEY JUDE BEATLES ACROSS THE UNIVERSE BEATLES SAW HER STANDING THERE BEATLES SOMETHING BEATLES HOLD YOUR HAND BEATLES HIDE YOUR LOVE AWAY BEATLES BLACK BIRD BEATLES ALWAYS A WOMEN BILLY JOEL PIANO MAN BILLY JOEL JUST THE WAY YOU ARE BILLY JOEL FOR THE LONGEST TIME BILLY JOEL YOU MAY BE RIGHT BILLY JOEL BLOWIN IN THE WIND BOB DYLAN DON’T THINK TWICE BOB DYLAN IT AINT ME BABY BOB DYLAN FIRST DAY OF MY LIFE BRIGHT EYES TRUE LOVE WAYS BUDDY HOLLY NOT FADE AWAY BUDDY HOLLY OH BOY BUDDY HOLLY COME DOWN BUSH GLYCERIN BUSH IF YOU WANT TO SING OUT CAT STEVENS FATHER AND SON CAT STEVENS WILD WORLD CAT STEVENS WE DON’T TALK ANYMORE CHARLIE PUTH ONE CALL AWAY CHARLIE PUTH TENESSEE WHISKY CHRIS STAPLETON SKY FULL OF STARS COLDPLAY HYMN FOR THE WEEKEND COLDPLAY SCIENTIST COLDPLAY MR JONES COUNTING CROWS ROUND HERE COUNTING CROWS TWO STEP DAVE MATTHEWS BAND SO MUCH TO SAY DAVE MATTHEWS BAND TOO MUCH DAVE MATTHEWS BAND CRASH INTO ME DAVE MATTHEWS BAND THE STONE DAVE MATTHEWS BAND GREY STREET DAVE MATTHEWS BAND TRIPPING BILLIES DAVE MATTHEWS BAND CRUSH DAVE MATTHEWS BAND FOR YOU DAVID RYAN HARRIS BRYAN HANSEN WILLIAM BLAKEY SONG LIST JAN 2018 HOLD ON WE'RE GOING HOME DRAKE PASSION FRUIT DRAKE HOTLINE BLING DRAKE SAVE TONIGHT EAGLE EYE CHERRY THINKING OUT LOUD ED SHEERAN PERFECT ED SHEERAN PHOTOGRAPH ED SHEERAN ROCKET MAN ELTON JOHN -

Project Creator and Pianist George Lepauw

OVERVIEW Pianist George Lepauw’s Bach48 is a multi-part project bringing to life Johann Sebastian Bach’s monumental Well-Tempered Clavier, a work often referred to as the “Old Testament of Music”. Bach48 is 1) A complete audio recording (5 hours) of the Well-Tempered Clavier by George Lepauw 2) A complete music film of the whole recording, by Martin Mirabel and Mariano Nante 3) A 33-minute documentary on the Well-Tempered Clavier and George’s journey to record it 4) A dedicated and growing website with a wealth of information on the project and the music 5) Bach48 Live: 48 live performances of Bach48 around the world (with masterclass option) 6) An art project that combines the Well-Tempered Clavier with photos and videos of water in its many states by artist Céline Oms, inspired by the meaning of Bach’s name (“river”) The Bach48 Album was produced by the Chicago-based International Beethoven Project non-profit organization between 2017 and 2020, in recognition of the Well-Tempered Clavier’s outsize influence on Beethoven’s education and inspiration, and in time for the worldwide celebration of Beethoven’s 250th birthday in 2020. It precedes a similar project focused on Beethoven’s Sonatas, currently in the works, to be released in 2021. The Bach48 Album was released in February 2020 by Orchid Classics as a 5-CD box-set distributed by Naxos and on major streaming services. Bach48 was made by a team of extraordinary people in Germany, France, Argentina, the UK and the USA: - Audio producer Harms Achtergarde - Film directors Martin Mirabel and Mariano Nante - Film editors Alejo Santos and Sebastiàn Palacio - Graphic designer Javier Reboursin - Webmaster Marcelo Perez - Photographer Céline Oms Learn more & watch the trailer: WWW.BACH48.COM BACH48 LIVE: 48 official performances There is nothing that replaces the emotional power of a live performance. -

Music by Women TABLE of CONTENTS

Music by Women TABLE OF CONTENTS Ordering Information 2 Folk/Singer-Songwriter 58 Ladyslipper On-Line! * Ladyslipper Listen Line 4 Country 64 New & Recent Additions 5 Jazz 65 Cassette Madness Sale 17 Gospel 66 Cards * Posters * Grabbags 17 Blues 67 Classical 18 R&B 67 Global 21 Cabaret 68 Celtic * British Isles 21 Soundtracks 68 European 27 Acappella 69 Latin American 28 Choral 70 Asian/Pacific 30 Dance 72 Arabic/Middle Eastern 31 "Mehn's Music" 73 Jewish 31 Comedy 76 African 32 Spoken 77 African Heritage 34 Babyslipper Catalog 77 Native American 35 Videos 79 Drumming/Percussion 37 Songbooks * T-Shirts 83 Women's Spirituality * New Age 39 Books 84 Women's Music * Feminist * Lesbian 46 Free Gifts * Credits * Mailing List * E-Mail List 85 Alternative 54 Order Blank 86 Rock/Pop 56 Artist Index 87 MAIL: Ladyslipper, 3205 Hillsborough Road. Durham NC 27705 USA PHONE ORDERS: 800-634-6044 (Mon-Fri 9-8, Sat 10-6 Eastern Time) ORDERING INFO FAX ORDERS: 800-577-7892 INFORMATION: 919-383-8773 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEB SITE: www.ladyslipper.org PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK-ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are FORMAT: Each description states which formats are don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and temporarily out of stock on a title, we will automati available: CD = compact disc, CS = cassette. Some schools). Make check or money order payable to cally back-order it unless you include alternatives recordings are available only on CD or only on cassette, Ladyslipper, Inc. -

We Are “The Droppers”

www.myspace.com/droppersmusic Phone: 714-321-2059 Email: [email protected] We are “The Droppers” The Droppers refuse to be your typical cliché band. They don't just want to be the music playing in the background of life. They want to capture your heart, mind, and soul with their melodies. The members want to inspire and connect with their audience on a level that has never been felt before. They believe in the intense power of their music and feel that you will as well. Joe Puccio (Lead Singer) was once quoted "Our songs are powerful because they are raw. Our songs come from our lives, true experiences, and emotions. Every lyric has a meaning. We don't use words for the sake of creating a song, or to "just make it fit." We use them to communicate and convey emotion. To Connect..." Their music will deliver a message to you that you will understand. Their motto is the title of their debut CD. "Live for today." Ramsey Sindaha (Lead Guitarist) states "We realize that we will be laying 6 feet under much longer than we are on top of this glorious planet. So we are just trying to live for fun and not the long run." That statement really touches base with most people. It's a true reflection of how each member lives their lives. Each of which is extremely dedicated to what they do, and they enjoy doing it to the fullest extent. No regrets. The band was originally founded by a small group of friends on a surf trip one fateful summer in Mexico. -

Music for the Connoisseur

DB0709_001_COVER.qxd 5/18/09 4:39 PM Page 1 DOWNBEAT 75TH ANNIVERSARY COLLECTOR’S EDITION 75TH ANNIVERSARY DownBeat.com $4.99 07 JULY 2009 JULY 0 09281 01493 5 JULY 2009 U.K. £3.50 DB0709_001b-001c_COVER.qxd 5/14/09 1:43 PM Page a2 DB0709_001b-001c_COVER.qxd 5/14/09 1:41 PM Page a3 DB0709_001_P4_COVER.qxd 5/14/09 1:47 PM Page a4 DB0709_002-005_MAST.qxd 5/14/09 1:50 PM Page 3 DB0709_002-005_MAST.qxd 5/14/09 1:51 PM Page 4 SEVENTY FIFTH ANNIVERSARY July 2009 VOLUME 76 – NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Jason Koransky Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 800-554-7470 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Norm Harris, D.D.