Benjamin Proust Fine Art Limited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Industry and the Ideal

INDUSTRY AND THE IDEAL Ideal Sculpture and reproduction at the early International Exhibitions TWO VOLUMES VOLUME 1 GABRIEL WILLIAMS PhD University of York History of Art September 2014 ABSTRACT This thesis considers a period when ideal sculptures were increasingly reproduced by new technologies, different materials and by various artists or manufacturers and for new markets. Ideal sculptures increasingly represented links between sculptors’ workshops and the realm of modern industry beyond them. Ideal sculpture criticism was meanwhile greatly expanded by industrial and international exhibitions, exemplified by the Great Exhibition of 1851, where the reproduction of sculpture and its links with industry formed both the subject and form of that discourse. This thesis considers how ideal sculpture and its discourses reflected, incorporated and were mediated by this new environment of reproduction and industrial display. In particular, it concentrates on how and where sculptors and their critics drew the line between the sculptors’ creative authorship and reproductive skill, in a situation in which reproduction of various kinds utterly permeated the production and display of sculpture. To highlight the complex and multifaceted ways in which reproduction was implicated in ideal sculpture and its discourse, the thesis revolves around three central case studies of sculptors whose work acquired especial prominence at the Great Exhibition and other exhibitions that followed it. These sculptors are John Bell (1811-1895), Raffaele Monti (1818-1881) and Hiram Powers (1805-1873). Each case shows how the link between ideal sculpture and industrial display provided sculptors with new opportunities to raise the profile of their art, but also new challenges for describing and thinking about sculpture. -

Venetian Early Modern Single-Leaf Prints After Contemporary Sculpture: Questions of Form and Function

Matej Klemenčič VENETIAN EARLY MODERN SINGLE-LEAF PRINTS AFTER CONTEMPORARY SCULPTURE: QUESTIONS OF FORM AND FUNCTION Riassunto rappresentare un singolo pezzo di scultu- ra e potevano essere realizzate per scopi Durante l’epoca moderna, sia la scultura di marketing, celebrativi o propagandistici classica che quella moderna furono spesso o altro ancora. L’articolo discute alcune di tradotte a stampa. Queste stampe sono state queste stampe singole, incise per illustrare pubblicate in diverse occasioni e utilizzate le opere dello scultore veneziano Antonio per vari scopi, spesso in serie con illustrazio- Corradini, e pubblicate a Venezia, Vienna e ni di importanti opere d’arte, come ad esem- Roma. Le incisioni vengono discusse in vi- pio a Roma, o come cataloghi di intere col- sta della loro funzione e dello sviluppo della lezioni di sculture. D’altra parte, potevano carriera di Corradini. Keywords: single-leaf prints, sculpture, Venice, Baroque, Antonio Corradini n one of his early drawings, Giambat- sculptor, therefore, whom Tiepolo wanted tista Tiepolo portrayed his colleagues to distinguish from the others, most prob- Iand friends, gathered sometime be- ably all of them painters. It would be in- tween 1716 and 1718 in a so-called “ac- triguing to identify him with one of the cademia del nudo”, a drawing academy younger Venetian sculptors of the time organised by Collegio dei pittori on Fon- but, unfortunately, there is little evidence damenta Nuove in contrada Santa Maria that would help us deduce his name.1 Formosa, in Venice (Fig. 1). Recently, the Even though our anonymous sculptor two figures on the right were identified as was carefully singled out by his contem- Gregorio Lazzarini (standing) and Antonio porary Tiepolo, at the time still a young, Balestra (sitting, and acting as a corrector), but already a very promising painter, this while the others remain anonymous. -

Two Letters of Bartolomeo Ammannati: Invention and Programme, Part I

TWO LETTERS OF BARTOLOMEO AMMANNATI: INVENTION AND PROGRAMME, PART I BARTOLOMEO AMMANNATI: “Al Magnifico Signor mio Osservandissimo [Bartolomeo Concino (?)] (...) Di Siena agli 3 di Novembre 1559”, from: Due lettere di Bartolommeo Ammannati scultore ed architetto fiorentino del secolo XVI [ed. Gaetano Milanesi], Firenze 1869 edited with an introduction and commentary by CHARLES DAVIS FONTES 46 [3 February 2010] Zitierfähige URL: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/volltexte/2010/893/ urn:nbn:de:bsz:16-artdok-8937 1 TWO LETTERS OF BARTOLOMEO AMMANNATI: INVENTION AND PROGRAMME Part I: BARTOLOMEO AMMANNATI, “Al Magnifico Signor mio Osservandissimo [Bartolomeo Concino (?)] (...) Di Siena agli 3 di Novembre 1559” Letter from Bartolomeo Ammannati in Siena to Bartolomeo Concini (?) in Florence, 3 November 1559 In 1869 there was printed in Florence on the occasion of the marriage of Eleonora Contucci of Montepulciano to Cesare Sozzifanti of Pistoia and as a tribute to the bride, a booklet of sixteen pages containing two unpublished letters written by the Florentine sculptor and architect Bartolomeo Ammannati (1511-1592). This publication belongs to a somewhat ephemeral category of occasional publications, common at the time, and usually privately printed for weddings and sometimes for other similarly significant life junctures, and, as such, marriage day publications represent a kind of afterlife of the classical epideictic type of the epithalamium (marriage hymn, praise of marriage day, etc.). The small book was: Due lettere di Bartolommeo Ammannati, scultore ed architetto fiorentino del secolo XVI, Firenze: Bencini, 1869. The first of the two letters, which describes the apparatus prepared for the entry of Cosimo I into Siena in 1560, is the subject of this issue of FONTES, and the second, which proposes the iconographical inventions devised by the artist for the base of a monumental honorific column to be erected in Florence, will be treated in a subsequent issue of FONTES, to appear shortly. -

ITALIAN ART SOCIETY NEWSLETTER XXIX, 3, Fall 2018

ITALIAN ART SOCIETY NEWSLETTER XXIX, 3, Fall 2018 An Affiliated Society of: College Art Association Society of Architectural Historians International Congress on Medieval Studies Renaissance Society of America Sixteenth Century Society & Conference American Association of Italian Studies President’s Message from Sean Roberts Rosen and I, quite a few of our officers and committee members were able to attend and our gathering in Rome September 15, 2018 served too as an opportunity for the Membership, Outreach, and Development committee to meet and talk strategy. Dear Members of the Italian Art Society: We are, as always, deeply grateful to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation for their support this past decade of these With a new semester (and a new academic year) important events. This year’s lecture was the last under our upon us once again, I write to provide a few highlights of current grant agreement and much of my time at the moment IAS activities in the past months. As ever, I am deeply is dedicated to finalizing our application to continue the grateful to all of our members and especially to those lecture series forward into next year and beyond. As I work who continue to serve on committees, our board, and to present the case for the value of these trans-continental executive council. It takes the hard work of a great exchanges, I appeal to any of you who have had the chance number of you to make everything we do possible. As I to attend this year’s lecture or one of our previous lectures to approach the end of my term as President this winter, I write to me about that experience. -

Cellini Vs Michelangelo: a Comparison of the Use of Furia, Forza, Difficultà, Terriblità, and Fantasia

International Journal of Art and Art History December 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 22-30 ISSN: 2374-2321 (Print), 2374-233X (Online) Copyright © The Author(s).All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijaah.v6n2p4 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/ijaah.v6n2p4 Cellini vs Michelangelo: A Comparison of the Use of Furia, Forza, Difficultà, Terriblità, and Fantasia Maureen Maggio1 Abstract: Although a contemporary of the great Michelangelo, Benvenuto Cellini is not as well known to the general public today. Cellini, a master sculptor and goldsmith in his own right, made no secret of his admiration for Michelangelo’s work, and wrote treatises on artistic principles. In fact, Cellini’s artistic treatises can be argued to have exemplified the principles that Vasari and his contemporaries have attributed to Michelangelo. This paper provides an overview of the key Renaissance artistic principles of furia, forza, difficultà, terriblità, and fantasia, and uses them to examine and compare Cellini’s famous Perseus and Medusa in the Loggia deiLanzi to the work of Michelangelo, particularly his famous statue of David, displayed in the Galleria dell’ Accademia. Using these principles, this analysis shows that Cellini not only knew of the artistic principles of Michelangelo, but that his work also displays a mastery of these principles equal to Michelangelo’s masterpieces. Keywords: Cellini, Michelangelo, Renaissance aesthetics, Renaissance Sculptors, Italian Renaissance 1.0Introduction Benvenuto Cellini was a Florentine master sculptor and goldsmith who was a contemporary of the great Michelangelo (Fenton, 2010). Cellini had been educated at the Accademiade lDisegno where Michelangelo’s artistic principles were being taught (Jack, 1976). -

Immodest Modesty

Immodest Modesty Marie GAILLE The Renaissance reinvented modesty—that contradictory passion which reveals while hiding. In a masterful book, Dominique Brancher shows how this art of circumvention spanned a variety of knowledge, especially medical knowledge, in the sixteenth century. Review of Dominique Brancher, Équivoques de la pudeur: Fabrique d’une passion à la Renaissance (Ambiguities of modesty: The production of a passion in the Renaissance), Genève, Droz, 2015, 904 pages, € 89. When entering the Sansevero Chapel Museum in Naples, one discovers not only Giuseppe Sanmartino’s extraordinary sculpture of the Veiled Christ (1775), but also a modesty statue— Pudicizia—executed by Antonio Corradini (1752). This white marble statue reveals its charms by concealing them with a veil so thin that it adapts to the smallest curves of the female body; meanwhile, its face turns away, eyes half closed, to escape direct confrontation with those of its admirer. The suggestive power of this sculpture illustrates how much the art of concealing can be associated with provocation, indecency, even obscenity. This ambivalence is particularly striking in the context of the Sansevero Chapel, a marble temple dedicated to the virtues and values cultivated by its founder, Prince of Sansevero, seventh of the name, which have little to do with the pleasures of the body and the charms of seduction: decorum, liberality, religious zeal, sweetness of the conjugal yoke, piety, disillusionment, sincerity, education, divine love. This ambivalence is the running theme of the book by Dominique Brancher, Équivoques de la pudeur: Fabrique d’une passion à la Renaissance. The book is a thoroughly original and ambitious one. -

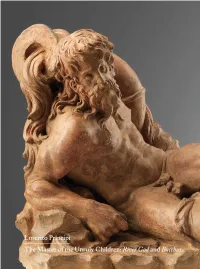

The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus TRINITY

TRINITY FINE ART Lorenzo Principi The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus London February 2020 Contents Acknowledgements: Giorgio Bacovich, Monica Bassanello, Jens Burk, Sara Cavatorti, Alessandro Cesati, Antonella Ciacci, 1. Florence 1523 Maichol Clemente, Francesco Colaucci, Lavinia Costanzo , p. 12 Claudia Cremonini, Alan Phipps Darr, Douglas DeFors , 2. Sandro di Lorenzo Luizetta Falyushina, Davide Gambino, Giancarlo Gentilini, and The Master of the Unruly Children Francesca Girelli, Cathryn Goodwin, Simone Guerriero, p. 20 Volker Krahn, Pavla Langer, Guido Linke, Stuart Lochhead, Mauro Magliani, Philippe Malgouyres, 3. Ligefiguren . From the Antique Judith Mann, Peta Motture, Stefano Musso, to the Master of the Unruly Children Omero Nardini, Maureen O’Brien, Chiara Padelletti, p. 41 Barbara Piovan, Cornelia Posch, Davide Ravaioli, 4. “ Bene formato et bene colorito ad imitatione di vero bronzo ”. Betsy J. Rosasco, Valentina Rossi, Oliva Rucellai, The function and the position of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Katharina Siefert, Miriam Sz ó´cs, Ruth Taylor, Nicolas Tini Brunozzi, Alexandra Toscano, Riccardo Todesco, in the history of Italian Renaissance Kleinplastik Zsófia Vargyas, Laëtitia Villaume p. 48 5. The River God and the Bacchus in the history and criticism of 16 th century Italian Renaissance sculpture Catalogue edited by: p. 53 Dimitrios Zikos The Master of the Unruly Children: A list of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Editorial coordination: p. 68 Ferdinando Corberi The Master of the Unruly Children: A Catalogue raisonné p. 76 Bibliography Carlo Orsi p. 84 THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. 1554) River God terracotta, 26 x 33 x 21 cm PROVENANCE : heirs of the Zalum family, Florence (probably Villa Gamberaia) THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/06/2021 05:38:06AM Via Free Access

Chapter �� The Musaeum: Its Contents 12.1 Introduction When Strada in 1568 thanked Duke Guglielmo of Mantua for the benefice conferred on his elder son Paolo, he offered the use of his house to the Duke, providing a brief description of its contents and adding that ‘most of these things have been seen by all those gentlemen of the court of Your Excellency that have been here [in Vienna]’.1 This confirms the accessibility of Strada’s Musaeum and the representative function it fulfilled. To have any idea of the impact the Musaeum had on such visitors, it is useful to provide a quick sketch of its contents. A sketch, an impression: not a reconstruction. There are a number of sourc- es which give a very elementary impression of what Strada’s studiolo may have looked like, and there are some other sources which give slightly more con- crete information on which specific objects, or type of objects, passed through his hands. Some of these—in particular the large-scale acquisitions of antique sculpture for the Duke of Bavaria in 1566–1569—were certainly not intended for Strada’s own collection, and they did never even come to Vienna. In most cases the information is too scanty to identify objects mentioned with any cer- tainty, or to determine what their destination was. We just do not know wheth- er Strada bought them on behalf of the Emperor, whether he bought them on commission from other patrons, whether he bought them on speculation— that is as a true art-dealer, hoping to sell them to the visitors of his house or dispose of them advantageously in some other way—or whether he bought them after all just for his own collection. -

Leon Battista Alberti

THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR ITALIAN RENAISSANCE STUDIES VILLA I TATTI Via di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy VOLUME 25 E-mail: [email protected] / Web: http://www.itatti.ita a a Tel: +39 055 603 251 / Fax: +39 055 603 383 AUTUMN 2005 From Joseph Connors: Letter from Florence From Katharine Park: he verve of every new Fellow who he last time I spent a full semester at walked into my office in September, I Tatti was in the spring of 2001. It T This year we have two T the abundant vendemmia, the large was as a Visiting Professor, and my Letters from Florence. number of families and children: all these husband Martin Brody and I spent a Director Joseph Connors was on were good omens. And indeed it has been splendid six months in the Villa Papiniana sabbatical for the second semester a year of extraordinary sparkle. The bonds composing a piano trio (in his case) and during which time Katharine Park, among Fellows were reinforced at the finishing up the research on a book on Zemurray Stone Radcliffe Professor outset by several trips, first to Orvieto, the medieval and Renaissance origins of of the History of Science and of the where we were guided by the great human dissection (in mine). Like so Studies of Women, Gender, and expert on the cathedral, Lucio Riccetti many who have worked at I Tatti, we Sexuality came to Florence from (VIT’91); and another to Milan, where were overwhelmed by the beauty of the Harvard as Acting Director. Matteo Ceriana guided us place, impressed by its through the exhibition on Fra scholarly resources, and Carnevale, which he had helped stimulated by the company to organize along with Keith and conversation. -

Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal Vol. 11, No. 1 • Fall 2016 The Cloister and the Square: Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D. Garrard eminist scholars have effectively unmasked the misogynist messages of the Fstatues that occupy and patrol the main public square of Florence — most conspicuously, Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus Slaying Medusa and Giovanni da Bologna’s Rape of a Sabine Woman (Figs. 1, 20). In groundbreaking essays on those statues, Yael Even and Margaret Carroll brought to light the absolutist patriarchal control that was expressed through images of sexual violence.1 The purpose of art, in this way of thinking, was to bolster power by demonstrating its effect. Discussing Cellini’s brutal representation of the decapitated Medusa, Even connected the artist’s gratuitous inclusion of the dismembered body with his psychosexual concerns, and the display of Medusa’s gory head with a terrifying female archetype that is now seen to be under masculine control. Indeed, Cellini’s need to restage the patriarchal execution might be said to express a subconscious response to threat from the female, which he met through psychological reversal, by converting the dangerous female chimera into a feminine victim.2 1 Yael Even, “The Loggia dei Lanzi: A Showcase of Female Subjugation,” and Margaret D. Carroll, “The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence,” The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 127–37, 139–59; and Geraldine A. Johnson, “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture,” Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, ed. -

Florence Celebrates the Uffizi the Medici Were Acquisitive, but the Last of the Line Was Generous

ArtNews December 1982 Florence Celebrates The Uffizi The Medici were acquisitive, but the last of the line was generous. She left all the family’s treasures to the people of Florence. by Milton Gendel Whenever I vist The Uffizi Gallery, I start with Raphael’s classic portrait of Leo X and Two Cardinals, in which the artist shows his patron and friend as a princely pontiff at home in his study. The pope’s esthetic interests are indicated by the finely worked silver bell on the red-draped table and an illuminated Bible, which he has been studying with the aid of a gold-mounted lens. The brass ball finial on his chair alludes to the Medici armorial device, for Leo X was Giovanni de’ Medici, the second son of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Clutching the chair, as if affirming the reality of nepotism, is the pope’s cousin, Cardinal Luigi de’ Rossi. On the left is Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici, another cousin, whose look of reverie might be read, I imagine, as foreseeing his own disastrous reign as Pope Clement VII. That was five years in the future, of course, and could not have been anticipated by Raphael, but Leo had also made cardinals of his three nephews, so it wasn’t unlikely that another member of the family would be elected to the papacy. In fact, between 1513 and 1605, four Medici popes reigned in Rome. Leo X was a true Renaissance prince, whose civility and love of the arts impressed everyone - in the tradition of his father, Lorenzo the Magnificent. -

Celebrating the City: the Image of Florence As Shaped Through the Arts

“Nothing more beautiful or wonderful than Florence can be found anywhere in the world.” - Leonardo Bruni, “Panegyric to the City of Florence” (1403) “I was in a sort of ecstasy from the idea of being in Florence.” - Stendahl, Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio (1817) “Historic Florence is an incubus on its present population.” - Mary McCarthy, The Stones of Florence (1956) “It’s hard for other people to realize just how easily we Florentines live with the past in our hearts and minds because it surrounds us in a very real way. To most people, the Renaissance is a few paintings on a gallery wall; to us it is more than an environment - it’s an entire culture, a way of life.” - Franco Zeffirelli Celebrating the City: the image of Florence as shaped through the arts ACM Florence Fall, 2010 Celebrating the City, page 2 Celebrating the City: the image of Florence as shaped through the arts ACM Florence Fall, 2010 The citizens of renaissance Florence proclaimed the power, wealth and piety of their city through the arts, and left a rich cultural heritage that still surrounds Florence with a unique and compelling mystique. This course will examine the circumstances that fostered such a flowering of the arts, the works that were particularly created to promote the status and beauty of the city, and the reaction of past and present Florentines to their extraordinary home. In keeping with the ACM Florence program‟s goal of helping students to “read a city”, we will frequently use site visits as our classroom.