Analysis of Biodiversity Threats & Opportunities in Malawi Resource Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Community-Based ART Service Model Linking Female Sex Workers to HIV Care and Treatment in Blantyre and Mangochi, Malawi

Population Council Knowledge Commons HIV and AIDS Social and Behavioral Science Research (SBSR) 1-1-2021 Assessment of community-based ART service model linking female sex workers to HIV care and treatment in Blantyre and Mangochi, Malawi Lung Vu Population Council Brady Zieman Population Council Adamson Muula Vincent Samuel Lyson Tenthani Population Council See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-hiv Part of the Public Health Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Vu, Lung, Brady Zieman, Adamson Muula, Vincent Samuel, Lyson Tenthani, David Chilongozi, Simon Sikwese, Grace Kumwenda, and Scott Geibel. 2021. "Assessment of community-based ART service model linking female sex workers to HIV care and treatment in Blantyre and Mangochi, Malawi," Project SOAR Final Report. Washington, DC: USAID | Project SOAR. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Population Council. Authors Lung Vu, Brady Zieman, Adamson Muula, Vincent Samuel, Lyson Tenthani, David Chilongozi, Simon Sikwese, Grace Kumwenda, and Scott Geibel This report is available at Knowledge Commons: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-hiv/ 551 Assessment of Community-based ART Service Model Linking Female Sex report Workers to HIV Care and Treatment in Blantyre and Mangochi, Malawi Lung Vu Brady Zieman Adamson Muula Vincent Samuel Lyson Tenthani David Chilongozi Simon Sikwese Grace Kumwenda JANUARY 2021 JANUARY Scott Geibel Project SOAR Population Council 4301 Connecticut Ave, NW, Suite 280 Washington, D.C. 20008 USA Tel: +1 202 237 9400 Fax: +1 202 237 8410 projsoar.org Project SOAR (Cooperative Agreement AID-OAA-A-14-00060) is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). -

Selous Game Reserve Tanzania

SELOUS GAME RESERVE TANZANIA Selous contains a third of the wildlife estate of Tanzania. Large numbers of elephants, buffaloes, giraffes, hippopotamuses, ungulates and crocodiles live in this immense sanctuary which measures almost 50,000 square kilometres and is relatively undisturbed by humans. The Reserve has a wide variety of vegetation zones, from forests and dense thickets to open wooded grasslands and riverine swamps. COUNTRY Tanzania NAME Selous Game Reserve NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SITE 1982: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria ix and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following Statement of Outstanding Universal Value at the time of inscription: Brief Synthesis The Selous Game Reserve, covering 50,000 square kilometres, is amongst the largest protected areas in Africa and is relatively undisturbed by human impact. The property harbours one of the most significant concentrations of elephant, black rhinoceros, cheetah, giraffe, hippopotamus and crocodile, amongst many other species. The reserve also has an exceptionally high variety of habitats including Miombo woodlands, open grasslands, riverine forests and swamps, making it a valuable laboratory for on-going ecological and biological processes. Criterion (ix): The Selous Game Reserve is one of the largest remaining wilderness areas in Africa, with relatively undisturbed ecological and biological processes, including a diverse range of wildlife with significant predator/prey relationships. The property contains a great diversity of vegetation types, including rocky acacia-clad hills, gallery and ground water forests, swamps and lowland rain forest. The dominant vegetation of the reserve is deciduous Miombo woodlands and the property constitutes a globally important example of this vegetation type. -

Private Investments to Support Protected Areas: Experiences from Malawi; Presented at the World Parks Congress

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264410164 Private Investments to Support Protected Areas: Experiences from Malawi; Presented at the World Parks Congress... Conference Paper · September 2003 DOI: 10.13140/2.1.4808.5129 CITATIONS READS 0 201 1 author: Daulos Mauambeta EnviroConsult Services 7 PUBLICATIONS 17 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Daulos Mauambeta on 01 August 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. Vth World Parks Congress: Sustainable Finance Stream September 2003 • Durban, South Africa Institutions Session Institutional Arrangements for Financing Protected Areas Panel C Private investments to support protected areas Private Investments to Support Protected Areas: Experiences from Malawi Daulos D.C. Mauambeta. Executive Director Wildlife and Environmental Society of Malawi. Private Bag 578. Limbe, MALAWI. ph: (265) 164-3428, fax: (265) 164-3502, cell: (265) 991-4540. E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract The role of private investments in supporting protected areas in Malawi cannot be overemphasized. The Government of Malawi’s Wildlife Policy (Malawi Ministry of Tourism, Parks and Wildlife 2000, pp2, 4) stresses the “development of partnerships with all interested parties to effectively manage wildlife both inside and outside protected areas and the encouragement of the participation of local communities, entrepreneurs, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and any other party with an interest in wildlife conservation”. -

Country Environmental Profile for Malawi

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES EC Framework Contract EuropeAid/119860/C/SV/multi Lot 6: Environment Beneficiaries: Malawi Request for Services N°2006/122946 Country Environmental Profile for Malawi Draft Report (Mrs. B. Halle, Mr. J. Burgess) August 2006 Consortium AGRIFOR Consult Parc CREALYS, Rue L. Genonceaux 14 B - 5032 Les Isnes - Belgium Tel : + 32 81 - 71 51 00 - Fax : + 32 81 - 40 02 55 Email : [email protected] ARCA Consulting (IT) – CEFAS (GB) - CIRAD (FR) – DFS (DE) – EPRD (PL) - FORENVIRON (HU) – INYPSA (ES) – ISQ (PT) – Royal Haskoning (NL) This report is financed by the European Commission and is presented by AGRIFOR Consult for the Government of Malawi and the European Commission. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Government of Malawi or the European Commission. Consortium AGRIFOR Consult 1 Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations 3 1. Summary 6 1.1 State of the environment 6 1.2 Environmental policy, legislative and institutional framework 8 1.3 EU and other donor co-operation with the Country from an environmental perspective 10 1.4 Conclusions and recommendations 11 2. State of the Environment 15 2.1 Physical and biological environment 15 2.1.1 Climate, climate change and climate variability 15 2.1.2 Geology and mineral resources 16 2.1.3 Land and soils 16 2.1.4 Water (lakes, rivers, surface water, groundwater) 17 2.1.5 Ecosystems and biodiversity 19 2.1.6 Risk of natural disasters 20 2.2 Socio-economic environment 21 2.2.1 Pressures on the natural resources 21 2.2.2 Urban areas and industries 31 2.2.3 Poverty and living conditions in human settlements 35 2.3 Environment situation and trends 37 2.4 Environmental Indicators 38 3. -

Lake Malawi Destination Guide

Lake Malawi Destination Guide Overview of Lake Malawi Occupying a fifth of the country, Lake Malawi is the third largest lake in Africa and home to more fish species than any other lake in the world. Also known as Lake Nyasa, it is often referred to as 'the calendar lake' because it is 365 miles (590km) long and 52 miles (85km) wide. Situated between Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania, this African Great Lake is about 40,000 years old, a product of the Great Rift Valley fault line. There are fishing villages to be found along the lakeshore where residents catch a range of local fish including chambo, kampango (catfish), lake salmon and tiger fish. The export of fish from the lake contributes significantly to the country's economy, and the delicious chambo, similar to bream, is served in most Malawian eateries. Visitors to Lake Malawi can see colourful mbuna fish in the water, while there are also occasional sightings of crocodiles, hippos, monkeys and African fish eagles along the shore. The nearby Eastern Miombo woodlands are home to African wild dogs. Swimming, snorkelling and diving are popular activities in the tropical waters of the lake, and many visitors also enjoy waterskiing, sailing and fishing. There are many options available for holiday accommodation at the lake, including resorts, guesthouses and caravan or camping parks. All budgets are catered for, with luxury lodges attracting the glamorous and humble campsites hosting families and backpackers. Cape Maclear is a well-developed lakeside town, and nearby Monkey Bay is a great holiday resort area. Club Makokola, near Mangochi, is also a popular resort. -

Community Based Natural Resource Management: Stocktaking Assessment

COMMUNITY BASED NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT: STOCKTAKING ASSESSMENT MALAWI PROFILE OCTOBER 2010 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI in collaboration with World Wildlife Fund, Inc. (WWF). COMMUNITY BASED NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT: STOCKTAKING ASSESSMENT MALAWI PROFILE Program Title: Capitalizing Knowledge, Connecting Communities Program (CK2C) Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Office of Acquisition and Assistance Contract Number: EPP-I-00-06-00021-00/01 Contractor: DAI Date of Publication: October 2010 Author: Daulos D.C. Mauambeta and Robert P.G. Kafakoma, Malawi CBNRM Forum, DAI Collaborating Partner: COPASSA project implemented by World Wildlife Fund, Inc. (WWF); Associate Cooperative Agreement Number: EPP-A-00-00004-00; Leader with Associate Award Number:LAG-A-00-99-00048-00 The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .........................................................................................................V ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................VII INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY ..................................................................................................... -

Species Accounts

Species accounts The list of species that follows is a synthesis of all the botanical knowledge currently available on the Nyika Plateau flora. It does not claim to be the final word in taxonomic opinion for every plant group, but will provide a sound basis for future work by botanists, phytogeographers, and reserve managers. It should also serve as a comprehensive plant guide for interested visitors to the two Nyika National Parks. By far the largest body of information was obtained from the following nine publications: • Flora zambesiaca (current ed. G. Pope, 1960 to present) • Flora of Tropical East Africa (current ed. H. Beentje, 1952 to present) • Plants collected by the Vernay Nyasaland Expedition of 1946 (Brenan & collaborators 1953, 1954) • Wye College 1972 Malawi Project Final Report (Brummitt 1973) • Resource inventory and management plan for the Nyika National Park (Mill 1979) • The forest vegetation of the Nyika Plateau: ecological and phenological studies (Dowsett-Lemaire 1985) • Biosearch Nyika Expedition 1997 report (Patel 1999) • Biosearch Nyika Expedition 2001 report (Patel & Overton 2002) • Evergreen forest flora of Malawi (White, Dowsett-Lemaire & Chapman 2001) We also consulted numerous papers dealing with specific families or genera and, finally, included the collections made during the SABONET Nyika Expedition. In addition, botanists from K and PRE provided valuable input in particular plant groups. Much of the descriptive material is taken directly from one or more of the works listed above, including information regarding habitat and distribution. A single illustration accompanies each genus; two illustrations are sometimes included in large genera with a wide morphological variance (for example, Lobelia). -

Central African Wilderness Safaris an Introduction To

An Introduction to Central African Wilderness Safaris Central African Wilderness Safaris is a responsible ecotourism and conservation company. We believe in providing specialist eco -tourism based safaris whilst protecting Malawi’s areas of pristine wilderness. We strive to preserve Malawi’s natural heritage and the biodivers ity it supports, whilst involving local communities in the process. Central African Wilderness Safaris offers an array of unique, exciting and diverse experiences in Malawi, the warm heart of Africa. With over twenty years of experience in the ecotourism i ndustry, we combine our highly personalized services and attention to detail to help meet your needs, keep you comfortable and ensure that your journey and time with us here in Malawi is truly unforgettable. Central African Wilderness Safaris P O Box 489, Sanctuary Lodge, Youth Drive, Lilongwe, Malawi T (00 265) 1 771 153/393 E(International inquiries) [email protected] or E(local inquiries) [email protected] www.cawsmw.com ABOUT MALAWI Malawi is a gem of a country in the heart of central southern Africa that offers a true African experience. Lake Malawi, the third largest water body in Africa, takes up almost a third of this narrow country. Malawi’s geography is sculptured by Africa’s Great Rift Valley: towering mountains, lush, fertile valley floors and enormous crystal- clear lakes are hallmarks of much of this geological phenomenon; and Malawi displays them all. At its lowest point, the country is only about 35m above sea level; its highest point, Mount Mulanje, is over 3 000m above sea level. Between these altitude extremes, the country’s diverse ecology is protected within Malawi’s nine national parks and game reserves; everything from elephants to orchids. -

Forest Health Monitoring in the Eastern Arc Mountains of Kenya and Tanzania: a Baseline Report on Selected Forest Reserves

Forest Health Monitoring in the Eastern Arc Mountains of Kenya and Tanzania: a baseline report on selected forest reserves Seif Madoffe, James Mwang’ombe, Barbara O’Connell, Paul Rogers, Gerard Hertel, and Joe Mwangi Dedicated to three team members, Professor Joe Mwangi, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya and Forest Department, Nairobi; Mr. Charles Kisena Mabula, Tanzania Forest Research Institute, Lushoto, and Mr. Onesmus Mwanganghi, National Museums of Kenya, Nairobi, who passed away shortly after the completion of the field work for this project. They will always be remembered. FHM EAM Baseline Report Acknowledgements Cooperating Agencies, Organizations, Institutions, and Individuals USDA Forest Service 1. Region 8, Forest Health Protection, Atlanta, GA – Denny Ward 2. Engineering (WO) – Chuck Dull 3. International Forestry (WO) – Marc Buccowich, Mellisa Othman, Cheryl Burlingame, Alex Moad 4. Remote Sensing Application Center, Salt Lake City, UT – Henry Lachowski, Vicky C. Johnson 5. Northeastern Research Station, Newtown Square, PA – Barbara O’Connell, Kathy Tillman 6. Rocky Mountain Research Station, Ogden, UT – Paul Rogers 7. Northeastern Area, State & Private Forestry, Newtown Square, PA – Gerard Hertel US Agency for International Development 1. Washington Office – Mike Benge, Greg Booth, Carl Gallegos, Walter Knausenberger 2. Nairobi, Kenya – James Ndirangu 3. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania – Dan Moore, Gilbert Kajuna Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania (Faculty of Forestry and Nature Conservation) – Seif Madoffe, R.C. -

Tanzania Environmental Threats and Opportunities Assessment

TANZANIA ENVIRONMENTAL THREATS AND OPPORTUNITIES ASSESSMENT November 2012 This Report was produced for review by the United States Agency for international Development (USAID). It was prepared by the Environmental Threats and Opportunities Assessment Team under contract to the US Department of Agriculture Forest Service – International Programs. Cover photo: Rice fields in Mkula Village, Kilombero Valley, Morogoro Region. Water from the Udzungwa Mountains National Park is used by the village to irrigate two crops of rice per year. Photo by B. Byers, June 2012. TANZANIA ENVIRONMENTAL THREATS AND OPPORTUNITIES ASSESSMENT November 2012 AUTHORITY Prepared for USAID-Tanzania. This Tanzania Environmental Threats and Opportunities Assessment is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of a Participating Agency Partnership Agreement (PAPA) No. AEG-T- 00-07-00003-00 between USAID and the USDA Forest Service International Programs. Funds were provided by USAID/Tanzania and facilitated by the USAID Bureau for Africa, Office of Sustainable Development, Economic Growth, Environment and Agriculture Division (AFR/SD/EGEA) under the Biodiversity Analysis and Technical Support (BATS) program. The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the ETOA Team and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government (USG). PREPARED BY ETOA Team: Bruce Byers (Team Leader), Zakiya Aloyce, Pantaleo Munishi, and Charles Rhoades. TABLE -

Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report

MIOMBO ECOREGION VISION REPORT Jonathan Timberlake & Emmanuel Chidumayo December 2001 (published 2011) Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 20 WWF - SARPO MIOMBO ECOREGION VISION REPORT 2001 (revised August 2011) by Jonathan Timberlake & Emmanuel Chidumayo Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 20 Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P.O. Box FM730, Famona, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe PREFACE The Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report was commissioned in 2001 by the Southern Africa Regional Programme Office of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF SARPO). It represented the culmination of an ecoregion reconnaissance process led by Bruce Byers (see Byers 2001a, 2001b), followed by an ecoregion-scale mapping process of taxa and areas of interest or importance for various ecological and bio-physical parameters. The report was then used as a basis for more detailed discussions during a series of national workshops held across the region in the early part of 2002. The main purpose of the reconnaissance and visioning process was to initially outline the bio-physical extent and properties of the so-called Miombo Ecoregion (in practice, a collection of smaller previously described ecoregions), to identify the main areas of potential conservation interest and to identify appropriate activities and areas for conservation action. The outline and some features of the Miombo Ecoregion (later termed the Miombo– Mopane Ecoregion by Conservation International, or the Miombo–Mopane Woodlands and Grasslands) are often mentioned (e.g. Burgess et al. 2004). However, apart from two booklets (WWF SARPO 2001, 2003), few details or justifications are publically available, although a modified outline can be found in Frost, Timberlake & Chidumayo (2002). Over the years numerous requests have been made to use and refer to the original document and maps, which had only very restricted distribution. -

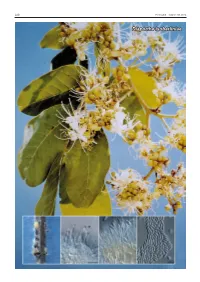

Diaporthe Isoberliniae Fungal Planet Description Sheets 221

220 Persoonia – Volume 32, 2014 Diaporthe isoberliniae Fungal Planet description sheets 221 Fungal Planet 236 – 10 June 2014 Diaporthe isoberliniae Crous, sp. nov. Etymology. Named after the host genus from which it was collected, Notes — Presently there are no known species of Diaporthe Isoberlinia. (incl. Phomopsis) that have been described from Isoberlinia. On PNA. Conidiomata pycnidial, globose, up to 300 µm diam, Furthermore, D. isoberliniae also appears to be phylogenetically black, erumpent, exuding creamy conidial droplets from central distinct from the species presently accommodated in GenBank, ostioles; walls of 3–6 layers of medium brown textura angularis. being most similar to sequences of D. foeniculacea, P. theicola Conidiophores hyaline, smooth, 2–3-septate, branched, densely and D. neotheicola. aggregated, cylindrical, straight to sinuous, 15–40 × 3–4 µm. ITS. Based on a megablast search of NCBIs GenBank nu- Conidiogenous cells 10–14 × 2.5–3 µm, phialidic, cylindrical, cleotide database, the closest hits using the ITS sequence terminal and lateral, with slight taper towards apex, 1 µm diam, are Diaporthe foeniculacea (GenBank KC343103; Identities with visible periclinal thickening; collarette flared, up to 4 µm = 541/558 (97 %), Gaps = 6/558 (1 %)), Phomopsis theicola long. Paraphyses not observed. Alpha conidia aseptate, hyaline, (GenBank HE774477; Identities = 534/551 (97 %), Gaps = smooth, guttulate, fusoid-ellipsoid, tapering towards both ends, 6/551 (1 %)) and Diaporthe neotheicola (GenBank KC145914; straight, apex subobtuse, base subtruncate, (6.5–)8–9(–10) × Identities = 561/579 (97 %), Gaps = 6/579 (1 %)). (2.5–)3(–3.5) µm. Gamma conidia not observed. Beta conidia LSU. Based on a megablast search of NCBIs GenBank nu- not observed.